EURASIA the Three 'Faces' of Russia's AI Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innovations and Technologies for the Navy and Maritime Areas

Special analytical export project of the United Industrial Publishing № 04 (57), June 2021 GOOD RESULT ASSAULT BOATS IDEX / NAVDEX 2021 QATAR & SPIEF-2021 Military Technical Russian BK-10 Russia at the two Prospective mutually Cooperation in 2020 for Sub-Saharan Africa expos in Abu Dhabi beneficial partnership .12 .18 .24 .28 Innovations and technologies for the navy and maritime areas SPECIAL PARTNERSHIP CONTENTS ‘International Navy & Technology Guide‘ NEWS SHORTLY № 04 (57), June 2021 EDITORIAL Special analytical export project 2 One of the best vessels of the United Industrial Publishing 2 Industrial Internet of ‘International Navy & Technology Guide’ is the special edition of the magazine Things ‘Russian Aviation & Military Guide’ 4 Trawler Kapitan Korotich Registered in the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information 4 Finance for 5G Technology and Mass Media (Roscomnadzor) 09.12.2015 PI № FS77-63977 Technology 6 The largest propeller 6 Protection From High-Precision Weapons 8 New Regional Passenger Aircraft IL-114-300 The magazine ‘Russian Aviation & Military Guide’, made by the United Industrial 8 Klimov presents design of Publishing, is a winner of National prize ‘Golden Idea 2016’ FSMTC of Russia VK-1600V engine 10 Russian Assault Rifles The best maritime General director technologies Editor-in-chief 10 ‘Smart’ Target for Trainin Valeriy STOLNIKOV 10th International Maritime Defence Show – IMDS-2021, which is held from 23 to 27 June Chief editor’s deputy 2021 in St. Petersburg under the Russian Govern- Elena SOKOLOVA MAIN TOPICS ment decree № 1906-r of 19.07.2019, is defi- Commercial director 12 Military Technical nitely unique. Show is gathering in obviously the Oleg DEINEKO best innovations for Navy and different maritime Cooperation technologies for any tasks. -

UN Chinese Language

WEEKLY UPDATED CURRENT AFFAIRS FOR WEEK 17/52 (19-25 APRIL) (2021) UN Chinese Language Day – Observed on Apr 20 UN Chinese Language Dayi s observed on April 20 The event was established by The UN Department of Public Information established the day in 2010 to celebrate multilingualism and cultural diversity as well as promote equal use of all six of its official working languages throughout the organization. Centre launches Startup India Seed Fund Scheme Union Minister for Commerce and Industry, Piyush Goyal launched the Startup India Seed Fund Scheme (SISFS). The Fund aims to provide financial assistance to startups for proof of concept, prototype development, product trials, market entry and commercialization. An amount of 945 crore rupees corpus will be divided over the next 4 years for providing seed funding to eligible startups through eligible incubators across India. The scheme is expected to support an estimated 3,600 startups through 300 incubators. Italy initiates First ever mega Food Park & Food processing unit in India Italyhas launched its first ever mega food park project in India, comprising of food processing facilities, in a bid to further strengthen ties between the two nations. The pilot project named “The Mega Food Park” was launched virtually on April 17, 2021 at Fanidhar Mega Food Park, in Gujarat. The project will develop a synergy between agriculture and industry of both countries, besides focusing on the research and development of newer, efficient technologies in the sector. Sivasubramanian Ramann appointed as SIDBI Chairman and Managing Director SIDBI informed Sivasubramanian Ramann has taken charge as Chairman and Managing Director of the bank. -

Saudi Reshuffles Council of Ministers

TWITTER CELEBS @newsofbahrain FRIDAY 8 To reclaim Baghdad, Iraqi artists grapple with its ghosts INSTAGRAM Cyrus, Hemsworth /nobmedia 28 now married LINKEDIN FRIDAY newsofbahrain DECEMBER 2018 Singer Miley Cyrus and WHATSAPP actor Liam Hemsworth 38444680 200 FILS are now reportedly ISSUE NO. 7974 married. They had orig- FACEBOOK /nobmedia inally planned to wed in their ocean-side home MAIL [email protected] in Malibu before it was destroyed in a wildlife. WEBSITE newsofbahrain.com | P13 Hazard wants to be a Chelsea ‘legend’ after hitting century mark 16 SPORTS WORLD 6 ‘Exit Afghan or face Soviet-style defeat’ Russia touts hypersonic missile speed Saudi reshuffles Council of Ministers Moscow, Russia TDT, Al Arabia ister of Media, while Hamad al- has replaced Turki al-Sheikh as Sheikh was appointed Minister president of the Sports Author- ussia touted yesterday a ing of Saudi Arabia Sal - of Education. ity, while Turki al-Sheikh has Rnew hypersonic missile Kman bin Abdulaziz Al Faisal bin Khalid was replaced been appointed as Chairman of said to hit speeds of more Saud yesterday issued a royal by Turki bin Talal as Governor of the Entertainment Authority. than 30,000 kilometres per decree reshaping the country’s the Asir region. Khalid bin Qarar al-Harbi has hour, amid heightened ten- cabinet. Sultan bin Salman has been been appointed the Director of sion with the US over arms A royal decree was also issued moved from the presidency Public Security. control. to restructure the Political and of the Tourism Authority and Bader bin Sultan was appoint- Russian President Security Affairs Council, head- appointed as Chairman of the ed Deputy to the Governor of Vladimir Putin on Wednes- ed by the Crown Prince, Prince Space Authority, which was Mecca and Eman al-Mutairi as day tracked final tests of a Mohammed bin Salman. -

The Russian Chronologies July - September 2009 Dr Mark a Smith

Research & Assessment Branch The Russian Chronologies July - September 2009 Dr Mark A Smith 09/13 RUSSIAN DOMESTIC CHRONOLOGY JULY 2009 – SEPTEMBER 2009 1 July 2009 The head of the commission for the Caucasus and first deputy speaker of the Federation Council, Aleksandr Torshin, criticises the assessment of the situation in the North Caucasus made by the human rights organization Amnesty International. 1 July 2009 President Dmitry Medvedev speaks at a state reception for graduates of military educational institutions in the Kremlin. He discusses military reform. 1 July 2009 Deputy Prime Minister Sergey Ivanov discusses with Vladimir Putin the development of seaport construction. Ivanov states: In 1998-99, of the total volume of import and export operations, 75 per cent of our cargoes were shipped through foreign ports, mostly Ukrainian and Baltic ones, and only 25 per cent through Russian ports. Now the proportion is as follows: 87 per cent of all cargoes are already shipped and processed through Russian ports, and only 13 per cent through foreign ports. I think that's fairly good dynamics, and in the foreseeable future we will completely get rid of dependence on foreign ports. This is very important from the economic point of view, and of course additional jobs. 1 July 2009 The head of the Rosnano state corporation Anatoly Chubays addresses the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs innovation policy committee. He discusses the need to develop an innovative economy in the Russian Federation. 1 July 2009 Interior Minister Rashid Nurgaliyev says that alcohol abuse or poisoning causes each fifth death in Russia. -

Annual Report | 2019-20 Ministry of External Affairs New Delhi

Ministry of External Affairs Annual Report | 2019-20 Ministry of External Affairs New Delhi Annual Report | 2019-20 The Annual Report of the Ministry of External Affairs is brought out by the Policy Planning and Research Division. A digital copy of the Annual Report can be accessed at the Ministry’s website : www.mea.gov.in. This Annual Report has also been published as an audio book (in Hindi) in collaboration with the National Institute for the Empowerment of Persons with Visual Disabilities (NIEPVD) Dehradun. Designed and Produced by www.creativedge.in Dr. S Jaishankar External Affairs Minister. Earlier Dr S Jaishankar was President – Global Corporate Affairs at Tata Sons Private Limited from May 2018. He was Foreign Secretary from 2015-18, Ambassador to United States from 2013-15, Ambassador to China from 2009-2013, High Commissioner to Singapore from 2007- 2009 and Ambassador to the Czech Republic from 2000-2004. He has also served in other diplomatic assignments in Embassies in Moscow, Colombo, Budapest and Tokyo, as well in the Ministry of External Affairs and the President’s Secretariat. Dr S. Jaishankar is a graduate of St. Stephen’s College at the University of Delhi. He has an MA in Political Science and an M. Phil and Ph.D in International Relations from Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi. He is a recipient of the Padma Shri award in 2019. He is married to Kyoko Jaishankar and has two sons & and a daughter. Shri V. Muraleedharan Minister of State for External Affairs Shri V. Muraleedharan, born on 12 December 1958 in Kanuur District of Kerala to Shri Gopalan Vannathan Veettil and Smt. -

Import Substitution for Rogozin

Import Substitution for Rogozin By Vladimir Voronov Translated by Arch Tait January 2016 This article is published in English by The Henry Jackson Society by arrangement with Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty. The article refects the views of the author and not necessarily those of The Henry Jackson Socity or its staf. IMPORT SUBSTITUTION FOR ROGOZIN 1 For the Russian armed forces and defence industry, ruptured ties with Ukraine and Western sanctions are proving disastrous. Calls for a full transition to using only Russian materials and components in the manufacture of military hardware have been heard coming out of the Kremlin since the Yeltsin era, but the problem has become acute since the operation involving Russian troops in Crimea. It came as no surprise that the agenda for Vladimir Putin’s 10 April 2014 meeting with the directors of the leading enterprises of the Russian military-industrial complex was unambiguously titled “To Consider Import Substitution Due to the Threat of Termination of Supplies from Ukraine of Products for a Number of Russian Industries”. The head of state expressed optimism, even before receiving a reply to his question of which Russian enterprises could increase production and how much it would all cost. Putin said he had “no doubt we will do it”, and that this “will be to the benefit of Russian industry and the economy: we will invest in developing our own manufacturing.”2 This confidence was evidently based on assurances from Denis Manturov, the Minister of Industry and Trade, who the previous day, had reported at a meeting between Putin and members of the government that his department had “already carried out a fairly in-depth analysis” and “concluded that our country is not seriously dependent on the supply of goods from Ukraine”. -

East Asian Strategic Review 2019

East Asian Strategic Review 2019 East Asian Strategic Review 2019 The National Institute for Defense Studies, Japan ISBN978-4-86482-074-5 Printed in Japan East Asian Strategic Review 2019 The National Institute for Defense Studies Japan Copyright © 2019 by the National Institute for Defense Studies First edition: July 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced in any form without written, prior permission from the National Institute for Defense Studies. This publication is an English translation of the original Japanese edition published in April 2019. EASR 2019 comprises NIDS researchers’ analyses and descriptions based on information compiled from open sources in Japan and overseas. The statements contained herein do not necessarily represent the official position of the Government of Japan or the Ministry of Defense. Edited by: The National Institute for Defense Studies 5-1 Ichigaya Honmura-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-8808, Japan URL: http://www.nids.mod.go.jp Translated and Published by: Urban Connections Osaki Bright Core 15F, 5-15, Kitashinagawa 5-chome, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 141-0001, Japan Phone: +81-3-6432-5691 URL: https://urbanconnections.jp/en/ ISBN 978-4-86482-074-5 The National Institute for Defense Studies East Asian Strategic Review 2019 Printed in Japan Cover photo Japan-India joint exercise (JIMEX18) (JMSDF Maritime Staff Office) Eighth Japan-Australia 2+2 Foreign and Defence Ministerial Consultations (Japan Ministry of Defense) F-35A fighter (JASDF Air Staff Office) Preface This edition of the East Asian Strategic Review (EASR) marks the twenty-third year of the flagship publication of the National Institute for Defense Studies (NIDS), Japan’s sole national think tank in the area of security affairs. -

4YZ R¶D Vh Wc` Ed Z Vrdevc =RUR\Y

- =" !%'!> ('!>> *)5"6'3.0 .$%.% / &.%(0 , )$.12 +3 "A @@<@ )A #@ 1O@ 1 #<1 1 9#$< <1 9 1@1 A <) @< B #<<)B<5':D <@< 1 1 1# 1 9 #1 1 19 B 1 1 1B11 ?# -4-: -75 ?1@!"(1! # %+/ +,+,7#'++ R The latest satellite images uation on ground with his com- R ! clearly indicate that the Chinese manders. ven as the two sides have have built infrastructure, includ- On the fresh Chinese build Q R Eagreed to disengage from ing black top roads and culverts up, the satellite images showed the Line of Actual Control (LAC) on the river in the Galwan val- the Chinese have re-erected an rouble seems to be in store R in Ladakh after the bloody clash ley inside the Indian region army post in the Galwan valley Tfor yoga guru Baba Ramdev killing 20 Indian Army person- thereby ringing alarm bells. which was removed by the on his claim to have developed Ministry task force. Everyone has nel, China is continuing with its However, there was no official Indians on June 15. This tem- Coronil — a drug for Covid-19 to send details of the research to military build-up in Galwan reaction to these developments porary structure is very close to cure. The Uttarakhand the AYUSH Ministry for con- valley and Depsang. They are so far. Patrolling Point 14. When the Government on Wednesday said firmation. This is the rule and no part of the eastern Ladakh Amid all these develop- month long face-offs started in Patanjali Ayurveda never dis- can advertise their products region. -

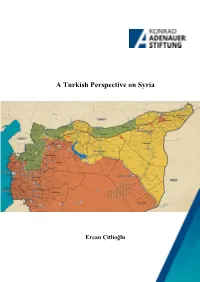

A Turkish Perspective on Syria

A Turkish Perspective on Syria Ercan Çitlioğlu Introduction The war is not over, but the overall military victory of the Assad forces in the Syrian conflict — securing the control of the two-thirds of the country by the Summer of 2020 — has meant a shift of attention on part of the regime onto areas controlled by the SDF/PYD and the resurfacing of a number of issues that had been temporarily taken off the agenda for various reasons. Diverging aims, visions and priorities of the key actors to the Syrian conflict (Russia, Turkey, Iran and the US) is making it increasingly difficult to find a common ground and the ongoing disagreements and rivalries over the post-conflict reconstruction of the country is indicative of new difficulties and disagreements. The Syrian regime’s priority seems to be a quick military resolution to Idlib which has emerged as the final stronghold of the armed opposition and jihadist groups and to then use that victory and boosted morale to move into areas controlled by the SDF/PYD with backing from Iran and Russia. While the east of the Euphrates controlled by the SDF/PYD has political significance with relation to the territorial integrity of the country, it also carries significant economic potential for the future viability of Syria in holding arable land, water and oil reserves. Seen in this context, the deal between the Delta Crescent Energy and the PYD which has extended the US-PYD relations from military collaboration onto oil exploitation can be regarded both as a pre-emptive move against a potential military operation by the Syrian regime in the region and a strategic shift toward reaching a political settlement with the SDF. -

Expanding Horizons Annual Report 2020 About the Report

EXPANDING HORIZONS ANNUAL REPORT 2020 ABOUT THE REPORT The Annual Report of Sovcomflot The accuracy of information contained in this (PAO Sovcomflot, the Company) for 2020 report is certified by the Auditing Commission includes the operating results of PAO Sovcomflot of the Company. and its subsidiaries, collectively referred to as Sovcomflot Group (SCF Group). It discloses the The report contains forward-looking statements operational and financial results, and certain related to operating, financial, economic and aspects of the activity and figures in the field of social indicators characterising the Company’s sustainable development. future development. The implementation of plans and intentions depends on the political, The report is prepared in accordance with the economic, social and legal situation in the requirements of the Regulation on Information Russian Federation an around the world. Disclosure by Issuers of Issue-Grade Securities Therefore, the actual results of the Company’s approved by Order of the Central Bank of the operations in the future may differ from those Russian Federation No. 454-P dated projected. 30 December 2014, by taking into account a model structure of the annual report of a joint- On 14 April 2021 the 2020 annual report of stock company whose shares are in federal PAO Sovcomflot was preliminarily approved ownership, as approved by Russian Government by the Company’s Board of Directors (Minutes resolution No. 1214 dated 31 December No. 206 of 14 April 2021) and approved by the 2010, and also by taking into account the Annual General Meeting of Shareholders. recommendations of the Corporate Governance Code of the Bank of Russia. -

Kesarev Memo | New Russian Government | January 2020

Kesarev phone: +32 (2) 899 4699 e-mail: [email protected] www.kesarev.com NEW RUSSIAN CABINET: STAFF “REVOLUTION” INSTEAD OF STRUCTURAL REFORMS? Summary On January 21, 2020, President Putin approved the structure of the new Russian Government and appointed Deputy Prime Ministers and federal Ministers. New Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin was appointed on January 16. What are the key specifics of the new Cabinet? The key specific feature of the new Russian Cabinet is that while the structural changes are minimal, the staff reshuffles proved to be radical, both in terms of the number of new people appointed to top offices and change of political status of key Cabinet members (how close they are to the President). This is an extremely atypical decision for Putin, compared to previous Cabinets over the entire period of his stay in power. Earlier, as a rule, the Cabinets included influential figures close to the President and personally associated with him, and a system of checks and balances between different elite groups existed. But at the same time, the decision to change the approach to the Cabinet appointments is logical in the context of a broader presidential “staff policy” over recent years - the so-called “technocratisation” of power (the appointment of young “technocratic” governors, the penetration of such figures into Medvedev’s second Cabinet, the appointment of the head of the Presidential Administration, a “technocrat” Anton Vayno during the Parliamentary election campaign in 2016 and the launch of “Leaders of Russia” contest in order to select and train a “succession pool” for the top positions in the federal and regional civil bureaucracy). -

Informational Materials

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 12/23/2020 8:36:08 AM Tuesday 12/22/20 This material is distributed by Ghebi LLC on behalf of Federal State Unitary Enterprise Rossiya Segodnya International Information Agency, and additional information is on file with the Department of Justice, Washington, District of Columbia. ‘Unlawful Conduct': US DoJ Sues Walmart for its Alleged Role in Fuelling Opioid Crisis Walmart The US opioid crisis started after health care providers began increasingly prescribing opioid medications, following reassurances from pharmaceutical companies in the late 1990s that patients would not become addicted, according to the US National Institute on Drug Abuse. Increased prescriptions and illegal sales led to widespread misuse. The Trump administration sued Walmart on Tuesday, accusing the multinational retail organization of helping to incite the US opioid epidemic by inadequately screening for questionable prescriptions despite warnings from its own pharmacists. According to a civil complaint filed Tuesday, the US Department of Justice (DoJ) has alleged that Walmart “unlawfully dispensed controlled substances from pharmacies it operated across the country and unlawfully distributed controlled substances to those pharmacies throughout the height of the prescription opioid crisis.” The complaint also states that Walmart’s alleged unlawful conduct caused hundreds of thousands of violations of the Controlled Substances Act, which regulates certain drugs. The DoJ is thus seeking injunctive relief and civil penalties, the latter of which could cost Walmart billions of dollars. “It has been a priority of this administration to hold accountable those responsible for the prescription opioid crisis. As one of the largest pharmacy chains and wholesale drug distributors in the country, Walmart had the responsibility and the means to help prevent the diversion of prescription opioids,” Jeffrey Bossert Clark, acting assistant attorney general of the DoJ's Civil Division, is quoted as saying in the department's release.