Practice Report Cluded That If Visually Impaired Students Learn Contractions at an Earlier Time, They Will Show Better Performance in Their Reading Skills

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Braillemathcodes Repository

Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on "Digitization and E-Inclusion in Mathematics and Science 2021" DEIMS2021, February 18–19, 2021, Tokyo _________________________________________________________________________________________ The BrailleMathCodes Repository Paraskevi Riga1, Theodora Antonakopoulou1, David Kouvaras1, Serafim Lentas1, and Georgios Kouroupetroglou1 1National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece Speech and Accessibility Laboratory, Department of Informatics and Telecommunications [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Math notation for the sighted is a global language, but this is not the case with braille math, as different codes are in use worldwide. In this work, we present the design and development of a math braille-codes' repository named BrailleMathCodes. It aims to constitute a knowledge base as well as a search engine for both students who need to find a specific symbol code and the editors who produce accessible STEM educational content or, in general, the learner of math braille notation. After compiling a set of mathematical braille codes used worldwide in a database, we assigned the corresponding Unicode representation, when applicable, matched each math braille code with its LaTeX equivalent, and forwarded with Presentation MathML. Every math symbol is accompanied with a characteristic example in MathML and Nemeth. The BrailleMathCodes repository was designed following the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. Users or learners of any code, both sighted and blind, can search for a term and read how it is rendered in various codes. The repository was implemented as a dynamic e-commerce website using Joomla! and VirtueMart. 1 Introduction Braille constitutes a tactile writing system used by people who are visually impaired. -

Unified English Braille Webinar Presentation

Unified English Braille: A Place to Start Webinar • UEB Ain't Hard to Do by Mark Brady a NYC Teacher of the Visually Impaired • The lyrics and sound file can be found on the Paths to Literacy website • http://www.pathstoliteracy.org/resources/farewell-song-9-ebae- contractions Unified English Braille A Place to Start April 2016 Donna Mayberry, M.Ed., NCUEB LAUREL REGIONAL PROGRAM, Lynchburg, VA [email protected] Webinar Content: • Overview of UEB • Unified English Braille Reference Sheets • Unified English Braille Student Progress Checklists • Converting Bookshare files into UEB • Teacher Relicensure: Option 8 • NCUEB • Questions Overview of UEB The Rules of Unified English Braille Second Edition 2013 Available as a PDF or BRF http://www.iceb.org/ueb.html Your new best Friend!!! What are teacher’s using to learn UEB? •Hadley School for the Blind •VDBVI Saturday Seminars •Update to UEB Self Directed Course- Available in Word, PDF, BRF, DXB http://www.cnib.ca/en/living/braille/Pages/Transcribers-UEB-Course.aspx •The new textbook that is being used in the VI Consortium is: Ashcroft's Programmed Instruction: Unified English Braille by M. Cay Holbrook 2014 Braille Not Used in Unified English Braille Contractions o'c o'clock (shortform) 4 dd (groupsign between letters) 6 to (wordsign unspaced from following word) 96 into (wordsign unspaced from following word) 0 by (wordsign unspaced from following word) # ble (groupsign following other letters) - com (groupsign at beginning of word) ,n ation (groupsign following other letters) ,y ally (groupsign following other letters) Braille Not Used in Unified English Braille- 2 Punctuation 7 opening and closing parentheses (round brackets) 7' closing square bracket 0' closing single quotation mark (inverted commas) ''' ellipsis -- dash (short dash) ---- double dash (long dash) ,7 opening square bracket Braille Not Used in Unified English Braille- 3 Composition signs (indicators) 1 non-Latin (non-Roman) letter indicator @ accent sign (nonspecific) @ print symbol indicator . -

Guidelines and Standards for Tactile Graphics, 2010

Guidelines and Standards for Tactile Graphics, 2010 Developed as a Joint Project of the Braille Authority of North America and the Canadian Braille Authority L'Autorité Canadienne du Braille Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2011 by The Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be downloaded and printed, but not altered or sold. The mission and purpose of the Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats; the ease of production by various methods; and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii Canadian Braille Authority (CBA) Members CNIB (Canadian National Institute for the Blind) Canadian Council of the Blind Braille Authority of North America (BANA) Members American Council of the Blind, Inc. (ACB) American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) American Printing House for the Blind (APH) Associated Services for the Blind (ASB) Association for Education & Rehabilitation of the Blind & Visually Impaired (AER) Braille Institute of America (BIA) California Transcribers & Educators for the Blind and Visually Impaired (CTEBVI) CNIB (Canadian National Institute for the Blind) The Clovernook Center for the Blind (CCBVI) National Braille Association, Inc. -

ONIX for Books Codelists Issue 40

ONIX for Books Codelists Issue 40 23 January 2018 DOI: 10.4400/akjh All ONIX standards and documentation – including this document – are copyright materials, made available free of charge for general use. A full license agreement (DOI: 10.4400/nwgj) that governs their use is available on the EDItEUR website. All ONIX users should note that this is the fourth issue of the ONIX codelists that does not include support for codelists used only with ONIX version 2.1. Of course, ONIX 2.1 remains fully usable, using Issue 36 of the codelists or earlier. Issue 36 continues to be available via the archive section of the EDItEUR website (http://www.editeur.org/15/Archived-Previous-Releases). These codelists are also available within a multilingual online browser at https://ns.editeur.org/onix. Codelists are revised quarterly. Go to latest Issue Layout of codelists This document contains ONIX for Books codelists Issue 40, intended primarily for use with ONIX 3.0. The codelists are arranged in a single table for reference and printing. They may also be used as controlled vocabularies, independent of ONIX. This document does not differentiate explicitly between codelists for ONIX 3.0 and those that are used with earlier releases, but lists used only with earlier releases have been removed. For details of which code list to use with which data element in each version of ONIX, please consult the main Specification for the appropriate release. Occasionally, a handful of codes within a particular list are defined as either deprecated, or not valid for use in a particular version of ONIX or with a particular data element. -

Nemeth Code Uses Some Parts of Textbook Format but Has Some Idiosyncrasies of Its Own

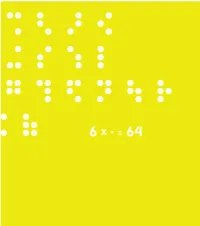

This book is a compilation of research, in “Understanding and Tracing the Problem faced by the Visually Impaired while doing Mathematics” as a Diploma project by Aarti Vashisht at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. 6 DOTS 64 COMBINATIONS A Braille character is formed out of a combination of six dots. Including the blank space, sixty four combinations are possible using one or more of these six dots. CONTENTS Introduction 2 About Braille 32 Mathematics for the Visually Impaired 120 Learning Mathematics 168 C o n c l u s i o n 172 P e o p l e a n d P l a c e s 190 Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION This project tries to understand the nature of the problems that are faced by the visually impaired within the realm of mathematics. It is a summary of my understanding of the problems in this field that may be taken forward to guide those individuals who are concerned about this subject. My education in design has encouraged interest in this field. As a designer I have learnt to be aware of my community and its needs, to detect areas where design can reach out and assist, if not resolve, a problem. Thus began, my search, where I sought to grasp a fuller understanding of the situation by looking at the various mediums that would help better communication. During the project I realized that more often than not work happened in individual pockets which in turn would lead to regionalization of many ideas and opportunities. Data collection got repetitive, which would delay or sometimes even hinder the process. -

World Braille Usage, Third Edition

World Braille Usage Third Edition Perkins International Council on English Braille National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped Library of Congress UNESCO Washington, D.C. 2013 Published by Perkins 175 North Beacon Street Watertown, MA, 02472, USA International Council on English Braille c/o CNIB 1929 Bayview Avenue Toronto, Ontario Canada M4G 3E8 and National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., USA Copyright © 1954, 1990 by UNESCO. Used by permission 2013. Printed in the United States by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data World braille usage. — Third edition. page cm Includes index. ISBN 978-0-8444-9564-4 1. Braille. 2. Blind—Printing and writing systems. I. Perkins School for the Blind. II. International Council on English Braille. III. Library of Congress. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. HV1669.W67 2013 411--dc23 2013013833 Contents Foreword to the Third Edition .................................................................................................. viii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... x The International Phonetic Alphabet .......................................................................................... xi References ............................................................................................................................ -

A Rapid Evidence Assessment of the Effectiveness of Educational Interventions to Support Children and Young People with Vision Impairment

SOCIAL RESEARCH NUMBER: 39/2019 PUBLICATION DATE: 12/09/2019 A Rapid Evidence Assessment of the effectiveness of educational interventions to support children and young people with vision impairment Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg. This document is also available in Welsh. © Crown Copyright Digital ISBN 978-1-83933-152-7 A Rapid Evidence Assessment of the effectiveness of educational interventions to support children and young people with vision impairment Author(s): Graeme Douglas, Mike McLinden, Liz Ellis, Rachel Hewett, Liz Hodges, Emmanouela Terlektsi, Angela Wootten, Jean Ware* Lora Williams* University of Birmingham and Bangor University* Full Research Report: < Douglas, G. et al (2019). A Rapid Evidence Assessment of the effectiveness of educational interventions to support children and young people with vision impairment. Cardiff: Welsh Government, GSR report number 39/2019.> Available at: https://gov.wales/rapid-evidence-assessment-effectiveness- educational-interventions-support-children-and-young-people-visual-impairment Views expressed in this report are those of the researcher and not necessarily those of the Welsh Government For further information please contact: David Roberts Social Research and Information Division Welsh Government Sarn Mynach Llandudno Junction LL31 9RZ 0300 062 5485 [email protected] Table of contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 5 2. Methodology ....................................................................................................... -

Braille ,,Basics ,,Plus

BRAILLE BASICS PLUS ,,BRAILLE ,,BASICS ,,PLUS Transition Booklet into Unified English Braille (UEB) By: Dr. Merry-Noel Chamberlain, TVI, NOMC Edited by Faye Miller, MA, TVI, COMS 2 INTRODUCTION With the recent changes in the Braille code, it can be confusing during this transition time for teachers and students alike. Some may come into contact with Braille signs that are from the old code while also being introduced to Unified English Braille (UEB). Braille Basics Plus has both the signs that have been discontinued as well as ‘some’ of the UEB code. This booklet has been designed to be a reference for parents, classroom teachers and beginner students learning the Braille code. It is not intended to have instructions on how to become a Braille transcriber in UEB. However, it can be a useful as a reference tool to Braille notes, holiday cards or to simply to look up a Braille sign. This booklet can also give some insights as to how the Braille contractions are connected within the code which can assist with learning Braille. THE BRAILLE BASICS The Braille code begins with a “cell” that consists of six dots as shown here → = and each dot has been assigned a number, as shown on the far right. → →→ →→ →→ 1 4 When the dots are arranged within the six locations, they represent letters, words, parts 2 5 of words, contractions, punctuations, and even numbers. For example, the letter ‘f’ 3 6 consists of dot numbers 1, 2, 4 and looks like this (f). All together there are 63 possible dot combinations within a single cell. -

The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs and Pictograms Free

FREE THE STORY OF WRITING: ALPHABETS, HIEROGLYPHS AND PICTOGRAMS PDF Andrew Robinson | 232 pages | 01 May 2007 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500286609 | English | London, United Kingdom Ancient Egypt's cryptic hieroglyphs | Nature A pictogram or pictograph is a symbol representing a concept, object, activity, place or event by illustration. Pictography is a form of writing whereby ideas are transmitted through drawing. It is the basis of cuneiform and hieroglyphs. Early written symbols were based on pictograms pictures which resemble what they signify and ideograms Hieroglyphs and Pictograms which represent ideas. It is commonly believed that pictograms appeared before ideograms. They were used by various ancient cultures all Hieroglyphs and Pictograms the world since around BC and began to develop into logographic writing systems around BC. Pictograms are still in use as the main medium of written communication in some non-literate cultures in Africa, The Americas, and Oceania, and are often used as simple symbols by most contemporary cultures. An ideogram or ideograph is a graphical symbol that represents an idea, rather than a group of letters arranged according to the phonemes of a spoken language, as is done in alphabetic languages. Examples of ideograms include wayfinding signage, such as in airports and other environments where many people may not be familiar with the language of the place they are in, as well as Arabic numerals and mathematical notation, which are used worldwide regardless of how they are pronounced in different languages. The term "ideogram" is commonly used to describe logographic writing systems such as Egyptian hieroglyphs and Chinese characters. However, symbols in logographic systems generally represent words or morphemes rather than pure ideas. -

Analysis of Teachers' Perceptions on Instruction of Braille Literacyin

ANALYSIS OF TEACHERS’ PERCEPTIONS ON INSTRUCTION OF BRAILLE LITERACYIN PRIMARY SCHOOLS FOR LEARNERS WITH VISUAL IMPAIRMENT IN KENYA CHOMBA M. WA MUNYI E83/27305/2014 A RESEARCHTHESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION SPECIAL NEEDS EDUCATION KENYATTA UNIVERSITY JUNE, 2017 ii DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of the university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgment has been made in the text. Signature _________________________ Date ______________________ Chomba M. WaMunyi E83/27305/2014 Supervisors: This dissertation has been submitted for appraisal with our/my approval as University supervisor(s). Signature _________________________ Date ______________________ Dr. Margaret Murugami Department of Special Needs Education, Kenyatta University Signature _________________________ Date ______________________ Dr. Stephen Nzoka Department of Special Needs Education, Kenyatta University Signature ________________________ Date ______________________ Prof. Desmond Ozoji Department of Special Education and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of JOS iii DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to all children with visual impairment in Kenya. iv v TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION ....................................................................................................... -

DBT and Japanese Braille

AUSTRALIAN BRAILLE AUTHORITY A subcommittee of the Round Table on Information Access for People with Print Disabilities Inc. www.brailleaustralia.org email: [email protected] Japanese braille and UEB Introduction Japanese is widely studied in Australian schools and this document has been written to assist those who are asked to transcribe Japanese into braille in that context. The Japanese braille code has many rules and these have been simplified for the education sector. Japanese braille has a separate code to that of languages based on the Roman alphabet and code switching may be required to distinguish between Japanese and UEB or text in a Roman script. Transcription for higher education or for a native speaker requires a greater knowledge of the rules surrounding the Japanese braille code than that given in this document. Ideally access to both a fluent Japanese reader and someone who understands all the rules for Japanese braille is required. The website for the Braille Authority of Japan is: http://www.braille.jp/en/. I would like to acknowledge the invaluable advice and input of Yuko Kamada from Braille & Large Print Services, NSW Department of Education whilst preparing this document. Kathy Riessen, Editor May 2019 Japanese print Japanese print uses three types of writing. 1. Kana. There are two sets of Kana. Hiragana and Katana, each character representing a syllable or vowel. Generally Hiragana are used for Japanese words and Katakana for words borrowed from other languages. 2. Kanji. Chinese characters—non-phonetic 3. Rōmaji. The Roman alphabet 1 ABA Japanese and UEB May 2019 Japanese braille does not distinguish between Hiragana, Katakana or Kanji. -

Perpustakaan Braille Di Kota Semarang

PERPUSTAKAAN BRAILLE DI KOTA SEMARANG TUGAS AKHIR UNTUK MEMPEROLEH GELAR SARJANA ARSITEKTUR Oleh Sadhu Adwitya Adhiwiajna 5112411017 PRODI ARSITEKTUR FAKULTAS TEKNIK SIPIL UNIVERSITAS NEGERI SEMARANG 2015 TUGAS AKHIR ustakaan Braille di Kota Semarang ii TUGAS AKHIR Perpustakaan Braille di Kota Semarang hapsoro adi iii TUGAS AKHIR ustakaan Braille di Kota Semarang iv TUGAS AKHIR Perpustakaan Braille di Kota Semarang hapsoro adi KATA PENGANTAR Segala puji syukur kami panjatkan kehadirat Allah SWT yang telah memberikan rahmat, taufik dan hidayah-Nya sehingga penyusun dapat menyelesaikan Landasan Program Perencanaan dan Perancangan Arsitektur (LP3A) Tugas Akhir Perpustakaan Braille di Kota Semarang ini dengan baik dan lancar tanpa terjadi suatu halangan apapun yang mungkin dapat mengganggu proses penyusunan LP3A Perpustakaan Braille ini. LP3A Perpustakaan Braille ini disusun sebagai salah satu syarat untuk kelulusan akademik di Universitas Negeri Semarang serta landasan dasar untuk merencanakan desain Perpustakaan Braille nantinya. Judul Tugas Akhir yang penulis pilih adalah ” Perpustakaan Braille di Kota Semarang”. Dalam penulisan LP3A Perpustakaan Braille ini tidak lupa penulis untuk mengucapkan terimakasih kepada semua pihak yang telah membantu, membimbing serta mengarahkan sehingga penulisan LP3A Perpustakaan Braille ini dapat terselesaikan dengan baik. Ucapan terimakasih saya tujukan kepada : 1. Allah SWT, yang telah memberikan kemudahan, kelancaran, serta kekekuatan sehingga dapat menyelesaikannya dengan baik 2. Bapak Prof. Dr. Fathur Rohman, M.Hum., Rektor Universitas Negeri Semarang 3. Bapak Dr. Nur Qudus, M.T., Dekan Fakultas Teknik Universitas Negeri Semarang 4. Bapak Drs. Sucipto, M.T., selaku Ketua Jurusan Teknik Sipil Universitas Negeri Semarang 5. Bapak Ir. Bambang Bambang Setyohadi K.P, M.T., selaku Kepala Program Studi Teknik Arsitektur S1 Universitas Negeri Semarang yang memberikan masukan, arahan dan ide-ide nya selama di perkuliahan 6.