Law and the Creative Mind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern District* Nathaniel Niles 673 31.6% Daniel Buck 452 21.2% Jonathan Hunt 235 11.0% Stephen Jacob 233 10.9% Lewis R

1794 (ctd.) Eastern District* Nathaniel Niles 673 31.6% Daniel Buck 452 21.2% Jonathan Hunt 235 11.0% Stephen Jacob 233 10.9% Lewis R. Morris 177 8.3% Cornelius Lynde 100 4.7% Paul Brigham 71 3.3% Lot Hall 58 2.7% Elijah Robinson 28 1.3% Stephen R. Bradley 17 0.8% Samuel Cutler 16 0.8% Reuben Atwater 13 0.6% Daniel Farrand 12 0.6% Royal Tyler 11 0.5% Benjamin Green 7 0.3% Benjamin Henry 5 0.2% Oliver Gallup 3 0.1% James Whitelaw 3 0.1% Asa Burton 2 0.1% Benjamin Emmons 2 0.1% Isaac Green 2 0.1% Israel Morey 2 0.1% William Bigelow 1 0.0% James Bridgman 1 0.0% William Buckminster 1 0.0% Alexander Harvey 1 0.0% Samuel Knight 1 0.0% Joseph Lewis 1 0.0% Alden Spooner 1 0.0% Ebenezer Wheelock 1 0.0% Total votes cast 2,130 100.0% Eastern District (February 10, 1795, New Election) Daniel Buck [Federalist] 1,151 56.4% Nathaniel Niles [Democratic-Republican] 803 39.3% Jonathan Hunt [Federalist] 49 2.4% Stephen Jacob [Federalist] 39 1.9% Total votes cast 2,042 100.0% General Election Results: U. S. Representative (1791-1800), p. 3 of 6 1796 Western District* Matthew Lyon 1783 40.7% Israel Smith 967 22.1% Samuel Williams 322 7.3% Nathaniel Chipman 310 7.1% Isaac Tichenor 287 6.5% Gideon Olin 198 4.5% Enoch Woodbridge 188 4.3% Jonas Galusha 147 3.4% Daniel Chipman 86 2.0% Samuel Hitchcock 52 1.2% Samuel Safford 8 0.2% Jonathan Robinson 5 0.1% Noah Smith 4 0.1% Ebenezer Marvin 3 0.1% William C. -

Warren, Vermont

VERMONT BI-CENrENNIAI. COMMEMORATIVE. s a special tribute to the Vermont State Bi-Centennial Celebration, the A Waitsfield-Fayston Telephone Company has compiled a commemorative historical section for the 1991 telephone directory. Many hours of preparation went into this special edition and we hope that you will find it informative and entertaining. In 1979, we published a similar telephone book to honor the 75th year of business for the Waitsfield-Fayston Telephone Company. Through the years, folks have hung onto these books and requests for additional copies continued long after our supply was drpleted. Should you desire additional copies of the 1991 edition, we invite you to pick them up at our Business Office, Waitstield Cable, or our nunierous directory racks in business and store locations throughout the Valley. Special thanks go out to the many people who authored the histories in this section and loaned us their treasured pictures. As you read these histories, please be sure to notice the credits after each section. Without the help of these generous people, this project would not have been possible. In the course of reading this historical section, other events and recollections may come to mind. likewise,, you may be able to provide further detail on the people and locations pictured in this collection. The Waitsfield-Fayston Telephone Company, through our interest in the Valley’s heritage, wishes to continue compiling historical documentation. We encourage you to share your thoughts, ideas and comments with us. @ HAPPY20oTH BIRTHDAYVERMONT!! VERMONT BICENTENNIAL, 1 VERMONYBI-CENTENNLAL CUMMEMORATWE @ IN THE BEGINNING@ f the Valley towns - Fayston, Moretown, Waitsfield and Warren - 0Moretown was the only one not chartered during the period between 1777 and 1791 when Vermont was an Independent Republic. -

Charles and Emmeline Linsley Papers

Charles (1795-1863) and Emmeline (1819-1895) Linsley Papers, 1827-1892 MSA 159 & MSA 159.1 Introduction The Charles and Emmeline Linsley Papers, 1827-1892, is a collection composed primarily of correspondence between Charles Linsley (1795-1863) of Middlebury, Vermont, his second wife, Emmeline Linsley (1819-1895), and members of their family. There are significant letters from Charles Linsely’s friend and associate, U. S. Senator Silas Wright (1795-1847). The collection was given to the Vermont Historical Society in 1988 by Mary Linsley Albert, great granddaughter of Charles Linsley (Ms. Acc. No. 88.15). It is stored in two Hollinger boxes and occupies .75 linear feet of shelf space. Biographical Sketches Charles Linsley (August 29, 1795-November 3, 1863), son of Judge Joel Linsley, was born in Cornwall, Vermont. He began studying law in Middlebury, Vermont and continued his studies under Chief Justice Royce of St. Albans, Vermont. He was admitted to the bar of Franklin County in 1823 and soon after returned to Middlebury, Vermont. He practiced law there until 1856, when he moved to Rutland, Vermont. He remained in Rutland until 1862, until, due to ill-health, he was forced to return to Middlebury, Vermont. He died in Middlebury on November 3, 1863. During his career, he served as director and solicitor of the Rutland and Burlington Railroad Company, and was Railroad Commissioner for two years under the Act of 1855. He served in the Vermont House of Representatives for Rutland County in 1858 and held federal appointments as District Attorney, 1845-1849, during the administration of President Polk, and as collector of Customs, 1860-1861, during the administration of President Buchanan. -

The Pennsylvania State College Library 4

= a'P THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE COLLEGE LIBRARY 4 / li,' 1 l 11I o, j,, I I ' I I.. 1'r, t , THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES j, 1, J,' id. l ... i. I' , il 1 s : _ ! at5 ' , . 1 _(st _ Berg % I 4 I A I i a Copyright Applied for by the Author . I ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~--- ALBERT H. BELL I MEMOIRS of THE BENCH AND BAR of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania By ALBERT H. BELL, Esq., of The Westmorcland Bar 2 DEDICATION To the Honorable James S. Moorhead, whose great ability, profound learning, high ideals and en- gaging personality have long made him a, distinguish- ed ornament to the Westmoreland Bar, a worthy exemplar to its members and the object of their high regard, and To the Honorable John B. Head, late an honored Judge of the Superior Court of Pennsylvania, to whom like attributes are ascribed and like tribute is due; to -these joint preceptors, their law student of the long ago, the author of these memoirs, in token of his obligation and affection, ventures to dedicate this volume. I 3 PREFACE These Memoirs had their origin in the request of Mr. E. Arthur Sweeny, editor of the "Morning Re- view", of Greensburg, to the, writer to prepare some character sketches of the deceased members of the Bench and Bar of Westmoreland County, the serial publication of which was to become a feature of that enterprising journal. They soon passed the stage of experiment, and the conception of fragmentary his- tory, and, in some degree, have become comprehen- sive of more than a century of the legal annals of the county. -

The Rise of Cornelius Peter Van Ness 1782- 18 26

PVHS Proceedings of the Vermont Historical Society 1942 NEW SERIES' MARCH VOL. X No. I THE RISE OF CORNELIUS PETER VAN NESS 1782- 18 26 By T. D. SEYMOUR BASSETT Cornelius Peter Van Ness was a colorful and vigorous leader in a formative period of Vermont history, hut he has remained in the dusk of that history. In this paper Mr. Bassett has sought to recall __ mm and IUs activities and through him throw definite light on h4s --------- eventfultime.l.- -In--this--study Van--N-esr--ir-brought;-w--rlre-dt:a.mot~ months of his attempt in the senatorial election of I826 to succeed Horatio Seymour. 'Ulhen Mr. Bassett has completed his research into thot phase of the career of Van Ness, we hope to present the re sults in another paper. Further comment will he found in the Post script. Editor. NDIVIDUALISM is the boasted virtue of Vermonters. If they I are right in their boast, biographies of typical Vermonters should re veal what individualism has produced. Governor Van Ness was a typical Vermonter of the late nineteenth century, but out of harmony with the Vermont spirit of his day. This essay sketches his meteoric career in administrative, legislative and judicial office, and his control of Vermont federal and state patronage for a decade up to the turning point of his career, the senatorial campaign of 1826.1 His family had come to N ew York in the seventeenth century. 2 His father was by trade a wheelwright, strong-willed, with little book-learning. A Revolutionary colonel and a county judge, his purchase of Lindenwald, an estate at Kinderhook, twenty miles down the Hudson from Albany, marked his social and pecuniary success.s Cornelius was born at Lindenwald on January 26, 1782. -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven. -

Martin's Bench and Bar of Philadelphia

MARTIN'S BENCH AND BAR OF PHILADELPHIA Together with other Lists of persons appointed to Administer the Laws in the City and County of Philadelphia, and the Province and Commonwealth of Pennsylvania BY , JOHN HILL MARTIN OF THE PHILADELPHIA BAR OF C PHILADELPHIA KKKS WELSH & CO., PUBLISHERS No. 19 South Ninth Street 1883 Entered according to the Act of Congress, On the 12th day of March, in the year 1883, BY JOHN HILL MARTIN, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. W. H. PILE, PRINTER, No. 422 Walnut Street, Philadelphia. Stack Annex 5 PREFACE. IT has been no part of my intention in compiling these lists entitled "The Bench and Bar of Philadelphia," to give a history of the organization of the Courts, but merely names of Judges, with dates of their commissions; Lawyers and dates of their ad- mission, and lists of other persons connected with the administra- tion of the Laws in this City and County, and in the Province and Commonwealth. Some necessary information and notes have been added to a few of the lists. And in addition it may not be out of place here to state that Courts of Justice, in what is now the Com- monwealth of Pennsylvania, were first established by the Swedes, in 1642, at New Gottenburg, nowTinicum, by Governor John Printz, who was instructed to decide all controversies according to the laws, customs and usages of Sweden. What Courts he established and what the modes of procedure therein, can only be conjectur- ed by what subsequently occurred, and by the record of Upland Court. -

Chipman Family a Genealogy Of

THE CHIPMAN FAMILY A GENEALOGY OF THE CHIPMANS IN AMERICA 1631-1920 BY BERT LEE CHIPMAN BERT L. CHIPMAN. PUBLISHER WINSTON-SALEM. N. C. COPYRIGHT 1920 BERT L. CHIPMAN MONOTYPED BY THE WINSTON PRINTING COMPANY WrN9TON-SALEM, N. C, Introduction Many hours have been spent in gathering and compiling the data that makes up this genealogy of the Chipman family; a correspondence has been carried on extending to every part of the United States and Canada, requiring several thousand letters; but it has been a pleasant task. What is proposed by genealogical research is not to laud individuals, nor to glorify such families as would other wise remain without glory. Heraldic arms have as little worth as military aside from the worth of those bearing them. Not the armor but the army merits and should best repay describing. It has been my earnest desire to make this work as complete and accurate as possible. In this connection I wish to acknowledge the valuable aid in research work rendered by Mr. W. A. Chipman (1788), Mr. S. L. Chip man (1959), Mrs. B. W. Gillespie (see 753) and Mrs. Margaret T. Reger (see 920). C Orgin THE NAME CHIPMAN is of English otjgin, early existing in various forms such as,-Chipenham, Chippenham, Chiepman and Chipnam. The name is to be found quite frequently in the books prepared by the Record Commis sion appointed by the British Parliament, and from i085 to 1350 it usually appears with the prefix de, as,~e Chippenham. Several towns in England bear the name in one of its f onns, for instance: Chippenham, Buckingham Co., twenty-two miles from London, is "a Liberty in the Parish and Hundred of Burnham, forming a part of the ancient demesnes of the crown and said to be the site of a palace of the Mercian kings." Chippenham, Cambridge Co., sixty-one miles from London, is '' a Parish in the Hundred of Staplehou, a dis charged Vicarage in the Archdeaconry of Suffolk and Diocese of Norwich." Chippenham, Wilts Co., ninety-three miles from London, is "a Borough, Market-town and Parish in the Hundred of Chippenham and a place of great antiquity. -

History Background Information

History Background Information Cumberland County has a rich history that continues to contribute to the heritage and identity of the county today. Events in the past have shaped the county as it has evolved over time. It is important to understand and appreciate the past in order to plan for the future. Introduction Historic landmarks and landscapes are important to the sense of place and history integral to the identity of communities. Preserving the physical fabric can involve many facets such as recognizing and protecting a single structure, an entire district, or the cultural landscape of a region. An advisory committee was formed to provide input and guidance for the development of this chapter. The committee included municipal representatives, county and municipal historical societies, and the Cumberland Valley Visitors Bureau. The development of this chapter was supported by a grant from the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. The Earliest Native Americans The first human inhabitants of the region arrived between 12 and 18 thousand years ago.1 We know very little about them except they were probably related to the Algonquian tribes that settled north of Pennsylvania. These early peoples were most likely nomadic hunters living in temporary or base camps. No villages of these ancient tribes have been found in Cumberland County, but many artifacts have been discovered to verify they populated the region. Artifacts found in the Cumberland Valley include notched arrow and spear points and grooved hatchets and axes of Algonquian origin.2 Approximately 3,000 years ago these native peoples began to cultivate crops, which included Indian corn or maize. -

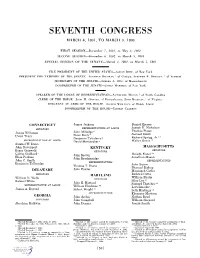

H. Doc. 108-222

SEVENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1801, TO MARCH 3, 1803 FIRST SESSION—December 7, 1801, to May 3, 1802 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1802, to March 3, 1803 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1801, to March 5, 1801 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—AARON BURR, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—ABRAHAM BALDWIN, 1 of Georgia; STEPHEN R. BRADLEY, 2 of Vermont SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—NATHANIEL MACON, 3 of North Carolina CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JOHN H. OSWALD, of Pennsylvania; JOHN BECKLEY, 4 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH WHEATON, of Rhode Island DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT James Jackson Daniel Hiester Joseph H. Nicholson SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas Plater James Hillhouse John Milledge 6 Peter Early 7 Samuel Smith Uriah Tracy 12 Benjamin Taliaferro 8 Richard Sprigg, Jr. REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE 13 David Meriwether 9 Walter Bowie Samuel W. Dana John Davenport KENTUCKY MASSACHUSETTS SENATORS Roger Griswold SENATORS 5 14 Calvin Goddard John Brown Dwight Foster Elias Perkins John Breckinridge Jonathan Mason John C. Smith REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Benjamin Tallmadge John Bacon Thomas T. Davis Phanuel Bishop John Fowler DELAWARE Manasseh Cutler SENATORS MARYLAND Richard Cutts William Eustis William H. Wells SENATORS Samuel White Silas Lee 15 John E. Howard Samuel Thatcher 16 REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE William Hindman 10 Levi Lincoln 17 James A. Bayard Robert Wright 11 Seth Hastings 18 REPRESENTATIVES Ebenezer Mattoon GEORGIA John Archer Nathan Read SENATORS John Campbell William Shepard Abraham Baldwin John Dennis Josiah Smith 1 Elected December 7, 1801; April 17, 1802. -

Sexuality, Spirituality, and the Love of God

Sexuality, Spirituality, and the Love of God: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Insights The Reverend Patrick J. Ryan, S.J. Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society Fordham University RESPONDENTS Sarit Kattan Gribetz, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Theology, Fordham University Amir Hussain, Ph.D. Professor of Theological Studies Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles TUESDAY, APRIL 9, 2019 | LINCOLN CENTER CAMPUS WEDNESDAY, APRIL 10, 2019 | ROSE HILL CAMPUS Sexuality, Spirituality, and the Love of God: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Insights The Reverend Patrick J. Ryan, S.J. Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society Fordham University The American comic writer and cartoonist, James Thurber (1894-1961), created a series of cartoons for The New Yorker more than sixty years ago under the general title, “The Battle of the Sexes.” It had no connection with later tennis games. Thurber was gradually losing his eyesight at the time and sometimes the cartoons arrived at their hilarious captions because of mistakes he had made in draftsmanship. I liked one in particular called “The Fight in the Grocery” which showed men and women firing bottles and cans at each other in the aisles of a small supermarket. In the Mesopotamian valley 6000 years ago, the battle of the sexes was a struggle between male and female gods. In the Akkadian creation epic, Enuma elish, the ordered cosmos is imaged as the result of previous violent interactions within the assembly of divine cosmic forces.1 When the mother-chaos figure, Ti’amat, imaginatively associated with the salt sea, resents the noise made by the younger generation of gods, war ensues. -

Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 11-12-1992 Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Earman, Cynthia Diane, "Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830" (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOARDINGHOUSES, PARTIES AND THE CREATION OF A POLITICAL SOCIETY: WASHINGTON CITY, 1800-1830 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Cynthia Diane Earman A.B., Goucher College, 1989 December 1992 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions.