U.S. Corporations in the 1790S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern District* Nathaniel Niles 673 31.6% Daniel Buck 452 21.2% Jonathan Hunt 235 11.0% Stephen Jacob 233 10.9% Lewis R

1794 (ctd.) Eastern District* Nathaniel Niles 673 31.6% Daniel Buck 452 21.2% Jonathan Hunt 235 11.0% Stephen Jacob 233 10.9% Lewis R. Morris 177 8.3% Cornelius Lynde 100 4.7% Paul Brigham 71 3.3% Lot Hall 58 2.7% Elijah Robinson 28 1.3% Stephen R. Bradley 17 0.8% Samuel Cutler 16 0.8% Reuben Atwater 13 0.6% Daniel Farrand 12 0.6% Royal Tyler 11 0.5% Benjamin Green 7 0.3% Benjamin Henry 5 0.2% Oliver Gallup 3 0.1% James Whitelaw 3 0.1% Asa Burton 2 0.1% Benjamin Emmons 2 0.1% Isaac Green 2 0.1% Israel Morey 2 0.1% William Bigelow 1 0.0% James Bridgman 1 0.0% William Buckminster 1 0.0% Alexander Harvey 1 0.0% Samuel Knight 1 0.0% Joseph Lewis 1 0.0% Alden Spooner 1 0.0% Ebenezer Wheelock 1 0.0% Total votes cast 2,130 100.0% Eastern District (February 10, 1795, New Election) Daniel Buck [Federalist] 1,151 56.4% Nathaniel Niles [Democratic-Republican] 803 39.3% Jonathan Hunt [Federalist] 49 2.4% Stephen Jacob [Federalist] 39 1.9% Total votes cast 2,042 100.0% General Election Results: U. S. Representative (1791-1800), p. 3 of 6 1796 Western District* Matthew Lyon 1783 40.7% Israel Smith 967 22.1% Samuel Williams 322 7.3% Nathaniel Chipman 310 7.1% Isaac Tichenor 287 6.5% Gideon Olin 198 4.5% Enoch Woodbridge 188 4.3% Jonas Galusha 147 3.4% Daniel Chipman 86 2.0% Samuel Hitchcock 52 1.2% Samuel Safford 8 0.2% Jonathan Robinson 5 0.1% Noah Smith 4 0.1% Ebenezer Marvin 3 0.1% William C. -

Warren, Vermont

VERMONT BI-CENrENNIAI. COMMEMORATIVE. s a special tribute to the Vermont State Bi-Centennial Celebration, the A Waitsfield-Fayston Telephone Company has compiled a commemorative historical section for the 1991 telephone directory. Many hours of preparation went into this special edition and we hope that you will find it informative and entertaining. In 1979, we published a similar telephone book to honor the 75th year of business for the Waitsfield-Fayston Telephone Company. Through the years, folks have hung onto these books and requests for additional copies continued long after our supply was drpleted. Should you desire additional copies of the 1991 edition, we invite you to pick them up at our Business Office, Waitstield Cable, or our nunierous directory racks in business and store locations throughout the Valley. Special thanks go out to the many people who authored the histories in this section and loaned us their treasured pictures. As you read these histories, please be sure to notice the credits after each section. Without the help of these generous people, this project would not have been possible. In the course of reading this historical section, other events and recollections may come to mind. likewise,, you may be able to provide further detail on the people and locations pictured in this collection. The Waitsfield-Fayston Telephone Company, through our interest in the Valley’s heritage, wishes to continue compiling historical documentation. We encourage you to share your thoughts, ideas and comments with us. @ HAPPY20oTH BIRTHDAYVERMONT!! VERMONT BICENTENNIAL, 1 VERMONYBI-CENTENNLAL CUMMEMORATWE @ IN THE BEGINNING@ f the Valley towns - Fayston, Moretown, Waitsfield and Warren - 0Moretown was the only one not chartered during the period between 1777 and 1791 when Vermont was an Independent Republic. -

Law and the Creative Mind

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 74 Issue 1 Symposium on Commemorating the Two Hundredth Anniversary of Chancellor Article 7 Kent's Ascension to the Bench December 1998 Law and the Creative Mind Susanna L. Blumenthal Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Susanna L. Blumenthal, Law and the Creative Mind, 74 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 151 (1998). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol74/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. LAW AND THE CREATIVE MIND SUSANNA L. BLUMENTHAL* INTR O D U CTIO N .......................................................................................152 I. THE JUDGE AND HIS WORK .......................................................161 II. THE CHARACTER OF THE JUDGE, 1800-1850 ...........................166 A. The Antebellum Portrait....................................................... 170 B. Literary Manifestations of Judicial Character.................... 177 III. THE GENIUS OF THE JUDGE, 1850-1900 ....................................187 A. Remembering the Fathers of the Bench ...............................195 B. Reconstructions of the JudicialIdeal ...................................202 C. Providence -

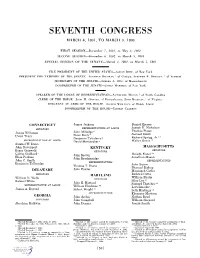

H. Doc. 108-222

SEVENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1801, TO MARCH 3, 1803 FIRST SESSION—December 7, 1801, to May 3, 1802 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1802, to March 3, 1803 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1801, to March 5, 1801 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—AARON BURR, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—ABRAHAM BALDWIN, 1 of Georgia; STEPHEN R. BRADLEY, 2 of Vermont SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—NATHANIEL MACON, 3 of North Carolina CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JOHN H. OSWALD, of Pennsylvania; JOHN BECKLEY, 4 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH WHEATON, of Rhode Island DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT James Jackson Daniel Hiester Joseph H. Nicholson SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas Plater James Hillhouse John Milledge 6 Peter Early 7 Samuel Smith Uriah Tracy 12 Benjamin Taliaferro 8 Richard Sprigg, Jr. REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE 13 David Meriwether 9 Walter Bowie Samuel W. Dana John Davenport KENTUCKY MASSACHUSETTS SENATORS Roger Griswold SENATORS 5 14 Calvin Goddard John Brown Dwight Foster Elias Perkins John Breckinridge Jonathan Mason John C. Smith REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Benjamin Tallmadge John Bacon Thomas T. Davis Phanuel Bishop John Fowler DELAWARE Manasseh Cutler SENATORS MARYLAND Richard Cutts William Eustis William H. Wells SENATORS Samuel White Silas Lee 15 John E. Howard Samuel Thatcher 16 REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE William Hindman 10 Levi Lincoln 17 James A. Bayard Robert Wright 11 Seth Hastings 18 REPRESENTATIVES Ebenezer Mattoon GEORGIA John Archer Nathan Read SENATORS John Campbell William Shepard Abraham Baldwin John Dennis Josiah Smith 1 Elected December 7, 1801; April 17, 1802. -

Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 11-12-1992 Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Earman, Cynthia Diane, "Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830" (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOARDINGHOUSES, PARTIES AND THE CREATION OF A POLITICAL SOCIETY: WASHINGTON CITY, 1800-1830 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Cynthia Diane Earman A.B., Goucher College, 1989 December 1992 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions. -

MIDNIGHT JUDGES KATHRYN Turnu I

[Vol.109 THE MIDNIGHT JUDGES KATHRYN TuRNu I "The Federalists have retired into the judiciary as a strong- hold . and from that battery all the works of republicanism are to be beaten down and erased." ' This bitter lament of Thomas Jefferson after he had succeeded to the Presidency referred to the final legacy bequeathed him by the Federalist party. Passed during the closing weeks of the Adams administration, the Judiciary Act of 1801 2 pro- vided the Chief Executive with an opportunity to fill new judicial offices carrying tenure for life before his authority ended on March 4, 1801. Because of the last-minute rush in accomplishing this purpose, those men then appointed have since been known by the familiar generic designation, "the midnight judges." This flight of Federalists into the sanctuary of an expanded federal judiciary was, of course, viewed by the Republicans as the last of many partisan outrages, and was to furnish the focus for Republican retaliation once the Jeffersonian Congress convened in the fall of 1801. That the Judiciary Act of 1801 was repealed and the new judges deprived of their new offices in the first of the party battles of the Jeffersonian period is well known. However, the circumstances surrounding the appointment of "the midnight judges" have never been recounted, and even the names of those appointed have vanished from studies of the period. It is the purpose of this Article to provide some further information about the final event of the Federalist decade. A cardinal feature of the Judiciary Act of 1801 was a reform long advocated-the reorganization of the circuit courts.' Under the Judiciary Act of 1789, the judicial districts of the United States had been grouped into three circuits-Eastern, Middle, and Southern-in which circuit court was held by two justices of the Supreme Court (after 1793, by one justice) ' and the district judge of the district in which the court was sitting.5 The Act of 1801 grouped the districts t Assistant Professor of History, Wellesley College. -

The Eighteenth-Century Debate About Equal Protection and Equal Civil Rights

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 1992 Equality and Diversity: The Eighteenth-Century Debate About Equal Protection and Equal Civil Rights Philip A. Hamburger Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Fourteenth Amendment Commons, Law and Philosophy Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Philip A. Hamburger, Equality and Diversity: The Eighteenth-Century Debate About Equal Protection and Equal Civil Rights, 1992 SUP. CT. REV. 295 (1992). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/482 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PHILIP A. HAMBURGER EQUALITY AND DIVERSITY: THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY DEBATE ABOUT EQUAL PROTECTION AND EQUAL CIVIL RIGHTS Living, as we do, in a world in which our discussions of equality often lead back to the desegregation decisions, to the Fourteenth Amendment, and to the antislavery debates of the 1830s, we tend to allow those momentous events to dominate our understanding of the ideas of equal protection and equal civil rights. Indeed, historians have frequently asserted that the idea of equal protection first developed in the 1830s in discussions of slavery and that it otherwise had little history prior to its adoption into the U.S. Constitution.1 Long before the Fourteenth Amendment, how- ever-long before even the 1830s-equal protection of the laws and equal civil rights were hardly notions unknown to Americans, who used these different standards of equality to address problems of religious diversity. -

"Vermonters Unmasked": Charles Phelps and the Patterns of Dissent in Revolutionary Vermont

HISTORY SUMMER 1989 VOL. 57, No. 3 133 "Vermonters Unmasked": Charles Phelps and the Patterns of Dissent in Revolutionary Vermont Phelps risked his life, suffered in prison, and lost most of his property in his struggle against Vermont authority. By J. KEVIN GRAFFAGNINO hen Timothy Phelps of Marlboro, Vermont, wrote to the grand jury of Windham County in May of 1813 , the subject was W murder. Phelps claimed possession of "a cloud of Evidence" proving that Ira Allen, Stephen Row Bradley, Jonas Galusha, and Moses Robinson had directed an " ungodly Cursed Crew" in the killings of Silvanus Fisk and Daniel Spicer. Fisk and Spicer had died at Guilford, Phelps informed the grand jurors, and their " Blood Cries Aloud to Heaven for Vengeance upon Those Murderers." Phelps had written to the grand jury in 1812, but the county had taken no action; now he demanded an immediate indictment. Word had just come of the recent death of Moses Robinson, and Phelps was worried that the other murderers might also pass away " before I Can have the pleasure and Satisfaction to hang them." If the jurors were hesitant to act against some of Vermont's most eminent past and present leaders, they could proceed unafraid: Phelps would offer them the full protection and weight of his considerable authority as " High Sheri ff of the County of Cumberland in the State of New York when those Two Men Ware Killed." That Fisk and Spicer had been dead for twenty-nine years was immaterial: murder was murder, and the need for legal action was clear. -

Social Structure and Political Factions in the Early Vermont Republic

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC RESEARCH AND POLICY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY WORKING PAPERS FACTIONAL POLITICS AND CREDIT NETWORKS IN REVOLUTIONARY VERMONT Henning Hillmann Department of Sociology Columbia University January 2003 ISERP WORKING PAPER 03-02 Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy Peter Bearman, Christina Gathmann, William McAllister, Florencia Torche, Harrison White and participants of the Historical Dynamics Workshop at Columbia University offered helpful comments and suggestions. For their assistance, I also wish to thank Sally Cook and Robin Haynes-Gardner at the Manchester Probate Court, Debbie Briggs at the Bennington Probate Court, and Susan Dunham and Seth Wheeler at the Marlboro Probate Court in Brattleboro. Earlier parts were presented at the 2002 European Conference for Network Analysis in Lille, and the 2002 Annual Meeting of the Social Science History Association in St. Louis. Financial support by the Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy at Columbia University is gratefully acknowledged. Correspondence may be directed to Henning Hillmann, Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy, Columbia University, 420 West 118th Street, 814 SIPA, New York, NY 10027. Email: [email protected]. 1 Abstract Studies of state formation tend to emphasize the demise of localism through centralization. This article specifies empirically the social structural conditions that strengthen localism under state formation. The historical case is the creation of Vermont during the Revolutionary War and the local factionalism it involved. Probate records are used to reconstruct credit networks that provided the relational foundation for localism and factional identities. -

Nathaniel Chipman to Alexander Hamilton, 14 July 1788

Nathaniel Chipman to Alexander Hamilton, Tinmouth, Vt. 14 July 17881 Your character as a federalist, has induced me, altho’ personally unknown to you, to address you on a subject of very great importance to the State of Vermont, of which I am a citizen, and from which, I think, may be derived a considerable advantage to the foederal Cause—Ten States have now adopted the new fœderal plan of government—That it will now Succeed is beyond a doubt—what disputes the other States may occasion, I know not— The people of this State, could certain obstacles be removed, I believe, might be induced almost unanimously to throw themselves into the fœderal Scale—you are not unacquainted with the Situation of a considerable part of our landed property—Many grants were formerly made, by the government 1 RC, Hamilton Papers, DLC. For Hamilton’s response, see his letter to Chipman dated 22 July (RCS:Vt., 153–54). The letter was delivered by Chipman’s brother Daniel, who, in a nineteenth-century biography, explained how the idea for the letter originated: Nathaniel Chipman . felt extremely anxious to devise some means by which the controversy with New York might be speedily adjusted. And in the early part of July [1788], a number of gentlemen, among whom were the late Judge [Lewis R.] Morris, then of Tinmouth, and the late Judge [Gideon] Olin, of Shaftsbury, met at his house in Tinmouth to hold a consultation on the subject, and they took this view of it. They said that Hamilton, Schuyler, Harrison, Benson, and other leading federalists in New York must be extremely anxious to have Vermont join the union, not only to add strength to the government, but to increase the weight of the northern and eastern states. -

1223 Table of Senators from the First Congress to the First Session of the One Hundred Twelfth Congress

TABLE OF SENATORS FROM THE FIRST CONGRESS TO THE FIRST SESSION OF THE ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS * ALABAMA 1805 1806 CLASS 2 Commence- Expiration of Congress Name of Senator ment of term term Remarks 16th–29th .. William R. King ................ Dec. 14, 1819 Mar. 3, 1847 Res. Apr. 15, 1844. 28th ............ Dixon H. Lewis ................. Apr. 22, 1844 Dec. 9, 1844 By gov., to fill vac. 28th–32d .... ......do ................................. Dec. 10, 1844 Mar. 3, 1853 Died Oct. 25, 1848. 30th–31st ... Benjamin Fitzpatrick ....... Nov. 25, 1848 Nov. 30, 1849 By gov., to fill vac. 31st–32d .... Jeremiah Clemens ............ Nov. 30, 1849 Mar. 3, 1853 33d–38th .... Clement Claiborne Clay, Mar. 4, 1853 Mar. 3, 1865 (1) Jr. 40th–41st ... Willard Warner ................ July 23, 1868 Mar. 3, 1871 (2) 42d–44th .... George Goldthwaite .......... Mar. 4, 1871 Mar. 3, 1877 (3) 45th–62d .... John T. Morgan ................ Mar. 4, 1877 Mar. 3, 1913 Died June 11, 1907. 60th ............ John H. Bankhead ........... June 18, 1907 July 16, 1907 By gov., to fill vac. 60th–68th .. ......do ................................. July 17, 1907 Mar. 3, 1925 Died Mar. 1, 1920. 66th ............ Braxton B. Comer ............ Mar. 5, 1920 Nov. 2, 1920 By gov., to fill vac. 66th–71st ... J. Thomas Heflin .............. Nov. 3, 1920 Mar. 3, 1931 72d–80th .... John H. Bankhead II ....... Mar. 4, 1931 Jan. 2, 1949 Died June 12, 1946. 79th ............ George R. Swift ................ June 15, 1946 Nov. 5, 1946 By gov., to fill vac. 79th–95th .. John Sparkman ................ Nov. 6, 1946 Jan. 2, 1979 96th–104th Howell Heflin .................... Jan. 3, 1979 Jan. 2, 1997 105th–113th Jeff Sessions .................... -

Minutes of the Sixth Annual Session of the Shelby Baptist Association, Held at Enon Church, Bibb County, Ala

Item No. 1 1. [Alabama Baptists]: MINUTES OF THE SIXTH ANNUAL SESSION OF THE SHELBY BAPTIST ASSOCIATION, HELD AT ENON CHURCH, BIBB COUNTY, ALA. FROM THE 10TH TO THE 13TH OCT., 1857. Centreville, Alabama: Central Enquirer Job Printing Office, 1857. Original printed yellow wrappers, stitched. 10, [2] pp. Lightly foxed, old Historical Society rubberstamp and withdrawal. Very Good. Centreville, the Bibb County seat, is a little town in south central Alabama. This rare imprint records the Constitution of the Shelby Association of Baptist Churches; minutes of proceedings and doings of the named participants; and a Statistical Table at the end. Not in Ellison. OCLC 641884320 [1- AAS] [as of March 2016]. $375.00 The Founding Documents of the American Jewish Publication Society 2. American Jewish Publication Society: CONSTITUTION AND BY-LAWS OF THE AMERICAN JEWISH PUBLICATION SOCIETY. (FOUNDED ON THE 9TH OF HESHVAN, 5606.) ADOPTED AT PHILADELPHIA, ON SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 1845, KISLEV 1, 5606. Philadelphia: C. Sherman, Printer. 5606 [i.e., 1845]. Contemporary plain wrappers [light rubberstamp of Dropsie College]. Stitched. 11, [1 blank] pp. Minor corner wear, Near Fine. This important organization was, according to the online Jewish Encyclopedia, “a society formed for the dissemination of Jewish literature, and the first of its kind in the United States; founded at Philadelphia in 1845 by Isaac Leeser.” Abraham Hart was President; Isaac Leeser was Corresponding Secretary and, along with Hyman Gratz and Abraham S. Wolf, one of the Managers. Leeser chaired the Publication Committee. The Constitution's Preamble commits to "fostering Jewish Literature, and of diffusing the utmost possible knowledge, among all classes of Israelites, of the tenets of their religion and the history of their people." Membership in the Society was open to "every male Israelite over the age of twenty-one years." Women, minors, and "non-Israelites" could become "contributing members." Parliamentary procedures and the organization of the Society are outlined.