"Vermonters Unmasked": Charles Phelps and the Patterns of Dissent in Revolutionary Vermont

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern District* Nathaniel Niles 673 31.6% Daniel Buck 452 21.2% Jonathan Hunt 235 11.0% Stephen Jacob 233 10.9% Lewis R

1794 (ctd.) Eastern District* Nathaniel Niles 673 31.6% Daniel Buck 452 21.2% Jonathan Hunt 235 11.0% Stephen Jacob 233 10.9% Lewis R. Morris 177 8.3% Cornelius Lynde 100 4.7% Paul Brigham 71 3.3% Lot Hall 58 2.7% Elijah Robinson 28 1.3% Stephen R. Bradley 17 0.8% Samuel Cutler 16 0.8% Reuben Atwater 13 0.6% Daniel Farrand 12 0.6% Royal Tyler 11 0.5% Benjamin Green 7 0.3% Benjamin Henry 5 0.2% Oliver Gallup 3 0.1% James Whitelaw 3 0.1% Asa Burton 2 0.1% Benjamin Emmons 2 0.1% Isaac Green 2 0.1% Israel Morey 2 0.1% William Bigelow 1 0.0% James Bridgman 1 0.0% William Buckminster 1 0.0% Alexander Harvey 1 0.0% Samuel Knight 1 0.0% Joseph Lewis 1 0.0% Alden Spooner 1 0.0% Ebenezer Wheelock 1 0.0% Total votes cast 2,130 100.0% Eastern District (February 10, 1795, New Election) Daniel Buck [Federalist] 1,151 56.4% Nathaniel Niles [Democratic-Republican] 803 39.3% Jonathan Hunt [Federalist] 49 2.4% Stephen Jacob [Federalist] 39 1.9% Total votes cast 2,042 100.0% General Election Results: U. S. Representative (1791-1800), p. 3 of 6 1796 Western District* Matthew Lyon 1783 40.7% Israel Smith 967 22.1% Samuel Williams 322 7.3% Nathaniel Chipman 310 7.1% Isaac Tichenor 287 6.5% Gideon Olin 198 4.5% Enoch Woodbridge 188 4.3% Jonas Galusha 147 3.4% Daniel Chipman 86 2.0% Samuel Hitchcock 52 1.2% Samuel Safford 8 0.2% Jonathan Robinson 5 0.1% Noah Smith 4 0.1% Ebenezer Marvin 3 0.1% William C. -

Warren, Vermont

VERMONT BI-CENrENNIAI. COMMEMORATIVE. s a special tribute to the Vermont State Bi-Centennial Celebration, the A Waitsfield-Fayston Telephone Company has compiled a commemorative historical section for the 1991 telephone directory. Many hours of preparation went into this special edition and we hope that you will find it informative and entertaining. In 1979, we published a similar telephone book to honor the 75th year of business for the Waitsfield-Fayston Telephone Company. Through the years, folks have hung onto these books and requests for additional copies continued long after our supply was drpleted. Should you desire additional copies of the 1991 edition, we invite you to pick them up at our Business Office, Waitstield Cable, or our nunierous directory racks in business and store locations throughout the Valley. Special thanks go out to the many people who authored the histories in this section and loaned us their treasured pictures. As you read these histories, please be sure to notice the credits after each section. Without the help of these generous people, this project would not have been possible. In the course of reading this historical section, other events and recollections may come to mind. likewise,, you may be able to provide further detail on the people and locations pictured in this collection. The Waitsfield-Fayston Telephone Company, through our interest in the Valley’s heritage, wishes to continue compiling historical documentation. We encourage you to share your thoughts, ideas and comments with us. @ HAPPY20oTH BIRTHDAYVERMONT!! VERMONT BICENTENNIAL, 1 VERMONYBI-CENTENNLAL CUMMEMORATWE @ IN THE BEGINNING@ f the Valley towns - Fayston, Moretown, Waitsfield and Warren - 0Moretown was the only one not chartered during the period between 1777 and 1791 when Vermont was an Independent Republic. -

Law and the Creative Mind

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 74 Issue 1 Symposium on Commemorating the Two Hundredth Anniversary of Chancellor Article 7 Kent's Ascension to the Bench December 1998 Law and the Creative Mind Susanna L. Blumenthal Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Susanna L. Blumenthal, Law and the Creative Mind, 74 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 151 (1998). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol74/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. LAW AND THE CREATIVE MIND SUSANNA L. BLUMENTHAL* INTR O D U CTIO N .......................................................................................152 I. THE JUDGE AND HIS WORK .......................................................161 II. THE CHARACTER OF THE JUDGE, 1800-1850 ...........................166 A. The Antebellum Portrait....................................................... 170 B. Literary Manifestations of Judicial Character.................... 177 III. THE GENIUS OF THE JUDGE, 1850-1900 ....................................187 A. Remembering the Fathers of the Bench ...............................195 B. Reconstructions of the JudicialIdeal ...................................202 C. Providence -

General Election Results: Governor, P

1798 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 6,211 66.4% Moses Robinson [Democratic Republican] 2,805 30.0% Scattering 332 3.6% Total votes cast 9,348 33.6% 1799 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 7,454 64.2% Israel Smith [Democratic Republican] 3,915 33.7% Scattering 234 2.0% Total votes cast 11,603 100.0% 1800 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 6,444 63.4% Israel Smith [Democratic Republican] 3,339 32.9% Scattering 380 3.7% Total votes cast 10,163 100.0% 1802 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 7,823 59.8% Israel Smith [Democratic Republican] 5,085 38.8% Scattering 181 1.4% Total votes cast 13,089 100.0% 1803 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 7,940 58.0% Jonathan Robinson [Democratic Republican] 5,408 39.5% Scattering 346 2.5% Total votes cast 13,694 100.0% 1804 2 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 8,075 55.7% Jonathan Robinson [Democratic Republican] 6,184 42.7% Scattering 232 1.6% Total votes cast 14,491 100.0% 2 Totals do not include returns from 31 towns that were declared illegal. General Election Results: Governor, p. 2 of 29 1805 3 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 8,683 61.1% Jonathan Robinson [Democratic Republican] 5,054 35.6% Scattering 479 3.4% Total votes cast 14,216 100.0% 3 Totals do not include returns from 22 towns that were declared illegal. 1806 4 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 8,851 55.0% Jonathan Robinson [Democratic Republican] 6,930 43.0% Scattering 320 2.0% Total votes cast 16,101 100.0% 4 Totals do not include returns from 21 towns that were declared illegal. -

Primary Sources Battle of Bennington Unit

Primary Sources Battle of Bennington Unit: Massachusetts Militia, Col. Simonds, Capt. Michael Holcomb James Holcomb Pension Application of James Holcomb R 5128 Holcomb was born 8 June 1764 and is thus 12 years old (!) when he first enlisted on 4 March 1777 in Sheffield, MA, for one year as a waiter in the Company commanded by his uncle Capt. Michael Holcomb. In April or May 1778, he enlisted as a fifer in Capt. Deming’s Massachusetts Militia Company. “That he attended his uncle in every alarm until some time in August when the Company were ordered to Bennington in Vermont […] arriving at the latter place on the 15th of the same month – that on the 16th his company joined the other Berkshire militia under the command of Col. Symonds – that on the 17th an engagement took place between a detachment of the British troops under the command of Col. Baum and Brechman, and the Americans under general Stark and Col. Warner, that he himself was not in the action, having with some others been left to take care of some baggage – that he thinks about seven Hundred prisoners were taken and that he believes the whole or a greater part of them were Germans having never found one of them able to converse in English. That he attended his uncle the Captain who was one of the guard appointed for that purpose in conducting the prisoners into the County of Berkshire, where they were billeted amongst the inhabitants”. From there he marches with his uncle to Stillwater. In May 1781, just before his 17th birthday, he enlisted for nine months in Capt. -

William Czar Bradley, 1782-1857

PROCEEDINGS OF THE VERMONT HISTORICAL SOCIETY FOR THE YEARS 1926-1927-1928 Copyrighted b y The Vermont Hist o rical Society 1928 William Czar Bradley 1782-1867 .by Justice Frank L. Fish, of the Vermont Supreme Court. Address delivered before the Vermont Historical Society at . Windsor, Vt., July 7, 1927. ---- WILLIAM CZAR BRADLEY The w·e stminster massacre occurred March 13, 1775. ltJesulted in the end of colonial rule and the sway of the King in Vermont . In December, 1778, the-first Vermont court was held at Bennington. This court was organized under the constit utional authority which had its inception here 150 years ago. In May, 1779, the second session of the court was held at Westminster. It was l].eld in tl].e court house built under the authority of the King in 1772 and moistened by the blood of William French and Daniel Houghton, the first martyrs of the Revolution. Th ~ Judges were Moses Robinson, Chief, and John Fassett, Jr., and Thomas Chandler Jr. Esquires. It was a jury session and 36 respondents were in jail awaiting trial. They were among the foremost citizens of the county of Cumberland and their plight was due to their having taken sides with New York. Their offence was that they had taken by force from William MeWain, an officer of Vermont, t wo co·ws which he had seized and offered to sell as the property of one Clay and another Williams, in default of their refus ing to serve in the State militia. It was a ury session and the purpose of the State was to try speedily, and without failure to convict, the accused. -

H. Doc. 108-222

FOURTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1795, TO MARCH 3, 1797 FIRST SESSION—December 7, 1795, to June 1, 1796 SECOND SESSION—December 5, 1796, to March 3, 1797 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—June 8, 1795, to June 26, 1795 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—JOHN ADAMS, of Massachusetts PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—HENRY TAZEWELL, 1 of Virginia; SAMUEL LIVERMORE, 2 of New Hampshire; WILLIAM BINGHAM, 3 of Pennsylvania SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—JONATHAN DAYTON, 4 of New Jersey CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JOHN BECKLEY, 5 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH WHEATON, of Rhode Island DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT GEORGIA Richard Potts 17 18 SENATORS SENATORS John Eager Howard Oliver Ellsworth 6 James Gunn REPRESENTATIVES James Hillhouse 7 James Jackson 14 8 Jonathan Trumbull George Walton 15 Gabriel Christie 9 Uriah Tracy Josiah Tattnall 16 Jeremiah Crabb 19 REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE 20 REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE William Craik Joshua Coit 21 Abraham Baldwin Gabriel Duvall Chauncey Goodrich Richard Sprigg, Jr. 22 Roger Griswold John Milledge George Dent James Hillhouse 10 James Davenport 11 KENTUCKY William Hindman Nathaniel Smith SENATORS Samuel Smith Zephaniah Swift John Brown Thomas Sprigg 12 Uriah Tracy Humphrey Marshall William Vans Murray Samuel Whittlesey Dana 13 REPRESENTATIVES DELAWARE Christopher Greenup MASSACHUSETTS SENATORS Alexander D. Orr John Vining SENATORS Henry Latimer MARYLAND Caleb Strong 23 REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE SENATORS Theodore Sedgwick 24 John Patten John Henry George Cabot 25 1 Elected December 7, 1795. -

Bushnell Family Genealogy, 1945

BUSHNELL FAMILY GENEALOGY Ancestry and Posterity of FRANCIS BUSHNELL (1580 - 1646) of Horsham, England And Guilford, Connecticut Including Genealogical Notes of other Bushnell Families, whose connections with this branch of the family tree have not been determined. Compiled and written by George Eleazer Bushnell Nashville, Tennessee 1945 Bushnell Genealogy 1 The sudden and untimely death of the family historian, George Eleazer Bushnell, of Nashville, Tennessee, who devoted so many years to the completion of this work, necessitated a complete change in its publication plans and we were required to start anew without familiarity with his painstaking work and vast acquaintance amongst the members of the family. His manuscript, while well arranged, was not yet ready for printing. It has therefore been copied, recopied and edited, However, despite every effort, prepublication funds have not been secured to produce the kind of a book we desire and which Mr. Bushnell's painstaking work deserves. His material is too valuable to be lost in some library's manuscript collection. It is a faithful record of the Bushnell family, more complete than anyone could have anticipated. Time is running out and we have reluctantly decided to make the best use of available funds by producing the "book" by a process of photographic reproduction of the typewritten pages of the revised and edited manuscript. The only deviation from the original consists in slight rearrangement, minor corrections, additional indexing and numbering. We are proud to thus assist in the compiler's labor of love. We are most grateful to those prepublication subscribers listed below, whose faith and patience helped make George Eleazer Bushnell's book thus available to the Bushnell Family. -

Hclassifi Cation

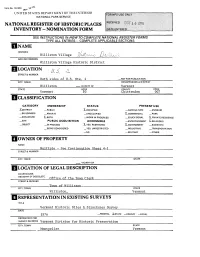

Form No. 10-300 ^ \Q~' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY ~ NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Williston Village AND/OR COMMON Williston Village Historic District LOCATION U.S. STREET & NUMBER Both sides of U.S. Rte. 2 _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Williston — VICINITY OF Vermont STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Vermont 50 Chit tend en 007 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE .X.DISTRICT _PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED X_COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE X_BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL K.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT X-RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED X-GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Multiple - See Continuation Sheet 4-1 STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.-ETC. Office of the Town Clerk STREET & NUMBER Town of Williston CITY. TOWN STATE Williston, Vermont REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Vermont Historic Sites § Structures Survey DATE 1976 —FEDERAL XSTATE _COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Vermont Division for Historic Preservation CITY. TOWN STATE Montpelier Vermont DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE XEXCELLENT _DETERIORATED X_UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE XGOOD _RUINS X_ALTERED X.MOVED DATE_____ XFAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Williston Village Historic District includes residential, commercial, municipal buildings and churches which line both sides of U.S. Route 2. The architecturally and historically significant buildings number approximately twenty-two. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Galusha House

Form No. 10-300 REV. <9/77) DATA SHEET UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY « NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Galusha House AND/OR COMMON "Fairview" LOCATION STREET & NUMBER _NOT FOR PUBLICATION ',f CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Jericho xv*~k ' __ VICINITY OF Vermont STATE CODE COUNTY CODE -.Vermont .. ., ••, --,50 . r -.. ; , .., .., Ctiittenden... -,, ., . 007.,*-^; CLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE _MUSEUM _XBUILDING<S> X-PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL 2LpRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —X.YES: RESTRICTED _GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —MILITARY- ,-. - - ,. —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME s/ Mr. and Mrs. Ray'F. Alien STREET & NUMBER 5971 S.W. 85 Street CITY, TOWN STATE Miami __ VICINITY OF Florida 33143 BLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS/ETC, Office.n.^^. ofr- the.-* Town™ Clerk/-i i STREETS NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Jericho Vermont OS465 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Vermont Historic Sites and Structures Survey DATE 1977 —FEDERAL X, STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Vermont Division .£or_.HisJ:Qzic_ Pres_eryatipn_. CITY, TOWN STATE Montpelier Vermont DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT -.DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE JK.GOOD _RUINS X-ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Galusha House is a handsome two-and-one-half story brick house laid in common bond, with a gable roof, set on a low stone foundation. -

This Is the Bennington Museum Library's “History-Biography” File, with Information of Regional Relevance Accumulated O

This is the Bennington Museum library’s “history-biography” file, with information of regional relevance accumulated over many years. Descriptions here attempt to summarize the contents of each file. The library also has two other large files of family research and of sixty years of genealogical correspondence, which are not yet available online. Abenaki Nation. Missisquoi fishing rights in Vermont; State of Vermont vs Harold St. Francis, et al.; “The Abenakis: Aborigines of Vermont, Part II” (top page only) by Stephen Laurent. Abercrombie Expedition. General James Abercrombie; French and Indian Wars; Fort Ticonderoga. “The Abercrombie Expedition” by Russell Bellico Adirondack Life, Vol. XIV, No. 4, July-August 1983. Academies. Reproduction of subscription form Bennington, Vermont (April 5, 1773) to build a school house by September 20, and committee to supervise the construction north of the Meeting House to consist of three men including Ebenezer Wood and Elijah Dewey; “An 18th century schoolhouse,” by Ruth Levin, Bennington Banner (May 27, 1981), cites and reproduces April 5, 1773 school house subscription form; “Bennington's early academies,” by Joseph Parks, Bennington Banner (May 10, 1975); “Just Pokin' Around,” by Agnes Rockwood, Bennington Banner (June 15, 1973), re: history of Bennington Graded School Building (1914), between Park and School Streets; “Yankee article features Ben Thompson, MAU designer,” Bennington Banner (December 13, 1976); “The fall term of Bennington Academy will commence (duration of term and tuition) . ,” Vermont Gazette, (September 16, 1834); “Miss Boll of Massachusetts, has opened a boarding school . ,” Bennington Newsletter (August 5, 1812; “Mrs. Holland has opened a boarding school in Bennington . .,” Green Mountain Farmer (January 11, 1811); “Mr. -

H. Doc. 108-222

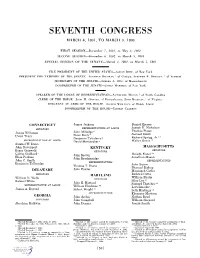

SEVENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1801, TO MARCH 3, 1803 FIRST SESSION—December 7, 1801, to May 3, 1802 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1802, to March 3, 1803 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1801, to March 5, 1801 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—AARON BURR, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—ABRAHAM BALDWIN, 1 of Georgia; STEPHEN R. BRADLEY, 2 of Vermont SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—NATHANIEL MACON, 3 of North Carolina CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JOHN H. OSWALD, of Pennsylvania; JOHN BECKLEY, 4 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH WHEATON, of Rhode Island DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT James Jackson Daniel Hiester Joseph H. Nicholson SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas Plater James Hillhouse John Milledge 6 Peter Early 7 Samuel Smith Uriah Tracy 12 Benjamin Taliaferro 8 Richard Sprigg, Jr. REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE 13 David Meriwether 9 Walter Bowie Samuel W. Dana John Davenport KENTUCKY MASSACHUSETTS SENATORS Roger Griswold SENATORS 5 14 Calvin Goddard John Brown Dwight Foster Elias Perkins John Breckinridge Jonathan Mason John C. Smith REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Benjamin Tallmadge John Bacon Thomas T. Davis Phanuel Bishop John Fowler DELAWARE Manasseh Cutler SENATORS MARYLAND Richard Cutts William Eustis William H. Wells SENATORS Samuel White Silas Lee 15 John E. Howard Samuel Thatcher 16 REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE William Hindman 10 Levi Lincoln 17 James A. Bayard Robert Wright 11 Seth Hastings 18 REPRESENTATIVES Ebenezer Mattoon GEORGIA John Archer Nathan Read SENATORS John Campbell William Shepard Abraham Baldwin John Dennis Josiah Smith 1 Elected December 7, 1801; April 17, 1802.