In the Lands of Sumer and Akkad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing and City Life

29 THEME2 writing and city life CITY life began in Mesopotamia*, the land between the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers that is now part of the Republic of Iraq. Mesopotamian civilisation is known for its prosperity, city life, its voluminous and rich literature and its mathematics and astronomy. Mesopotamia’s writing system and literature spread to the eastern Mediterranean, northern *The name Syria, and Turkey after 2000 BCE, so that the kingdoms of Mesopotamia is that entire region were writing to one another, and to the derived from the Pharaoh of Egypt, in the language and script of Mesopotamia. Greek words mesos, Here we shall explore the connection between city life and writing, and then look at some outcomes of a sustained meaning middle, tradition of writing. and potamos, In the beginning of recorded history, the land, mainly the meaning river. urbanised south (see discussion below), was called Sumer and Akkad. After 2000 BCE, when Babylon became an important city, the term Babylonia was used for the southern region. From about 1100 BCE, when the Assyrians established their kingdom in the north, the region became known as Assyria. The first known language of the land was Sumerian. It was gradually replaced by Akkadian around 2400 BCE when Akkadian speakers arrived. This language flourished till about Alexander’s time (336-323 BCE), with some regional changes occurring. From 1400 BCE, Aramaic also trickled in. This language, similar to Hebrew, became widely spoken after 1000 BCE. It is still spoken in parts of Iraq. Archaeology in Mesopotamia began in the 1840s. At one or two sites (including Uruk and Mari, which we discuss below), excavations continued for decades. -

Ancient Mesopotamia Akkdadian Empire Reading Comprehension

ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA AKKDADIAN EMPIRE READING COMPREHENSION *Article *10 Matching Questions *10 True/False Questions *4 Multiple Choice Questions *Key Included Name____________________ ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA- AKKADIAN EMPIRE The Akkadian Empire was the first Empire to rule all of Mesopotamia. It lasted about 200 years from 2300 BC to 2100 BC. Originally the Sumerians lived in the southern part of Mesopotamia and the Akkadians lived in the northern part. They had similar governments and cultures, but spoke different languages. The governments had individual city-states, where each city had its own ruler that controlled the city and the surrounding area. The city-states were not initially united and often warred with one another. Eventually, the Akkadian rulers started to see the advantage to uniting many of their cities under a single nation and began forming alliances to work together. Sargon the Great rose to power around 2300 BC. According to Sumerian literature, Sargon was born to an Akkadian high priestess and a poor father, maybe a gardener. His mother abandoned him by putting him a reed woven basket and let it float down the river, like Moses a thousand years later. Sargon was rescued and made friends with the goddess Ishtar and was brought up in the king’s court. Sargon built himself a new city at Akkad and made himself the king of it when he grew up. He gradually conquered all the land around it, making the Akkadian Empire. The powerful Sumerian city of Uruk attacked Akkad, but they fought back and eventually conquered Uruk. Sargon went on to conquer all of the Sumerian city-states and united northern and southern Mesopotamia under a single ruler. -

Seminary Studies

ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY STUDIES VOLUME VI JANUARI 1968 NUMBER I CONTENTS Heimmerly-Dupuy, Daniel, Some Observations on the Assyro- Babylonian and Sumerian Flood Stories Hasel, Gerhard F., Sabbatarian Anabaptists of the Sixteenth Century: Part II 19 Horn, Siegfried H., Where and When was the Aramaic Saqqara Papyrus Written ? 29 Lewis, Richard B., Ignatius and the "Lord's Day" 46 Neuffer, Julia, The Accession of Artaxerxes I 6o Specht, Walter F., The Use of Italics in English Versions of the New Testament 88 Book Reviews iio ANDREWS UNIVERSITY BERRIEN SPRINGS, MICHIGAN 49104, USA ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY STUDIES The Journal of the Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary of Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan SIEGFRIED H. HORN Editor EARLE HILGERT KENNETH A. STRAND Associate Editors LEONA G. RUNNING Editorial Assistant SAKAE Kos() Book Review Editor ROY E. BRANSON Circulation Manager ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY STUDIES publishes papers and short notes in English, French and German on the follow- ing subjects: Biblical linguistics and its cognates, textual criticism, exegesis, Biblical archaeology and geography, an- cient history, church history, theology, philosophy of religion, ethics and comparative religions. The opinions expressed in articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the editors. ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY STUDIES is published in January and July of each year. The annual subscription rate is $4.00. Payments are to be made to Andrews University Seminary Studies, Berrien Springs, Michigan 49104, USA. Subscribers should give full name and postal address when paying their subscriptions and should send notice of change of address at least five weeks before it is to take effect; the old as well as the new address must be given. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49596-7 — the Amorites and the Bronze Age Near East Aaron A

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49596-7 — The Amorites and the Bronze Age Near East Aaron A. Burke Index More Information INDEX ꜤꜢmw (Egyptian term), 145–47 See also Asiatics “communities of practice,” 18–20, 38–40, 42, (Egypt) 347–48 decline of, 350–51 A’ali, 226 during Early Bronze Age, 31 ‘Aa-zeh-Re’ Nehesy, 316–17 Ebla, 38–40, 56, 178 Abarsal, 45 emergence of, 23, 346–47 Abda-El (Amorite), 153–54 extensification of, 18–20 Abi-eshuh, 297, 334–35 hollow cities, 178–79 Abisare (Larsa), 160 Jazira, 38, 177 Abishemu I (Byblos), 175 “land rush,” 177–78 Abraham, 6 Mari, 38–40, 56, 177–79, 227–28 abu as symbolic kinship, 268–70 Nawar, 38, 40, 42 Abu en-Ni’aj, Tell, 65 Northern Levant, 177 Abu Hamad, 54 Qatna, 179 Abu Salabikh, 100 revival of, 176–80, 357 Abusch, Tzvi, 186 Shubat Enlil, 177–78, 180 Abydos, 220 social identity of Amorites and, 10 Achaemenid Empire, 12 Urkesh, 38, 42 Achsaph, 176 wool trade and, 23 ‘Adabal (deity), 40 Yamḫ ad, 179 Adad/Hadad (deity), 58–59, 134, 209–10, 228–29, zone of uncertainty and, 24, 174 264, 309–11, 338, 364 Ahbabu, 131 Adams, Robert, 128 Ahbutum (tribe), 97 Adamsah, 109 Ahktoy III, 147 Adba-El (Mari), 153–54 Ahmar, Tell, 51–53, 56, 136, 228 Addahushu (Elam), 320 Ahmose, 341–42 Ader, 50 ‘Ai, 33 Admonitions of Ipuwer, 172 ‘Ain Zurekiyeh, 237–38 aDNA. See DNA Ajjul, Tell el-, 142, 237–38, 326, 329, 341–42 Adnigkudu (deity), 254–55 Akkadian Empire. -

Melammu: the Ancient World in an Age of Globalization Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge

Melammu: The Ancient World in an Age of Globalization Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Series Editors Ian T. Baldwin, Jürgen Renn, Dagmar Schäfer, Robert Schlögl, Bernard F. Schutz Edition Open Access Development Team Lindy Divarci, Nina Ruge, Matthias Schemmel, Kai Surendorf Scientific Board Markus Antonietti, Antonio Becchi, Fabio Bevilacqua, William G. Boltz, Jens Braarvik, Horst Bredekamp, Jed Z. Buchwald, Olivier Darrigol, Thomas Duve, Mike Edmunds, Fynn Ole Engler, Robert K. Englund, Mordechai Feingold, Rivka Feldhay, Gideon Freudenthal, Paolo Galluzzi, Kostas Gavroglu, Mark Geller, Domenico Giulini, Günther Görz, Gerd Graßhoff, James Hough, Man- fred Laubichler, Glenn Most, Klaus Müllen, Pier Daniele Napolitani, Alessandro Nova, Hermann Parzinger, Dan Potts, Sabine Schmidtke, Circe Silva da Silva, Ana Simões, Dieter Stein, Richard Stephenson, Mark Stitt, Noel M. Swerdlow, Liba Taub, Martin Vingron, Scott Walter, Norton Wise, Gerhard Wolf, Rüdiger Wolfrum, Gereon Wolters, Zhang Baichun Proceedings 7 Edition Open Access 2014 Melammu The Ancient World in an Age of Globalization Edited by Markham J. Geller (with the cooperation of Sergei Ignatov and Theodor Lekov) Edition Open Access 2014 Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Proceedings 7 Proceedings of the Sixth Symposium of the Melammu Project, held in Sophia, Bulgaria, September 1–3, 2008. Communicated by: Jens Braarvig Edited by: Markham J. Geller Editorial Team: Lindy Divarci, Beatrice Hermann, Linda Jauch -

Sargon of Akkad: the Akkadian Empire Around the Year 2350

Sargon of Akkad: The Akkadian Empire Around the year 2350 B.C.E., a powerful Mesopotamian leader named Sargon took control of northern and southern Mesopotamia and established the world’s first empire. An empire brings together many different peoples and lands under control of one ruler, called an emperor. Your task is to analyze the documents throughout this assignment and formulate a complete understanding of Sargon and his Akkadian Empire. How was Sargon able to establish this empire? Why did his empire last? Why should the Akkadian Empire be considered important to world history? WHAT IMPORTANT INFORMATION DO WE LEARN ABOUT DOCUMENT #1 SARGON AND HIS EMPIRE FROM DOCUMENT 1? DOCUMENTS 2 &3 WHAT IMPORTANT INFORMATION DO WE LEARN ABOUT SARGON AND HIS EMPIRE FROM DOCUMENTS 2/3? Sargon’s Military Force DOCUMENT #4 WHAT IMPORTANT INFORMATION DO WE LEARN ABOUT SARGON AND HIS EMPIRE FROM DOCUMENT 4? As with most early Mesopotamian kings, we know little about Sargon the Great. Cuneiform records indicate that in his 50-year reign, he fought no fewer than 34 wars. One account suggests that his core military force numbered 5,400 men; if that account is accurate, then Sargon’s standing army at full mobilization would have constituted the largest army of the time by far. Unlike leaders of the previous wars between rival city-states, Sargon created a national empire that would have required a much larger force than usual to sustain it, and he and his heirs did for 300 years. Sargon faced the same problem as Alexander the Great would eventually face. -

Sumero-Babylonian King Lists and Date Lists A

XI Sumero-Babylonian King Lists and Date Lists A. R. GEORGE The Antediluvian King List The antediluvian king list is an Old Babylonian (b) a tablet from Nippur, now in Istanbul text, composed in Sumerian, that purports to (Kraus 1952: 31) document the reigns of successive kings of (c) another reportedly from Khafaje (Tutub), remote antiquity, from the time when the gods now in Berkeley, California (Finkelstein first transmitted to mankind the institution of 1963: 40) kingship until the interruption of human histo- (d) a further tablet now in the Karpeles Manu- ry by the great Flood. The list exists in several script Library, Santa Barbara, California, versions. Sometimes it appears as the opening given below in a preliminary transliteration section of the Sumerian King List, as in text (No. 97) No. 98 below. More often it occurs as an inde- (e) a small fragment from Nippur now in Phil- pendent list, of which one example is held by adelphia that bears lines from the list fol- the Schøyen collection, published here as text lowed by other text (Peterson 2008). No. 96. Other examples of the Old Babylonian A more extensive treatment of the lists of ante- list of antediluvian kings copied independently diluvian kings, including No. 96 and the tablet of the Sumerian King List are: in the Karpeles Manuscript Library, is promised (a) the tablet W-B 62, of uncertain prove- by Gianni Marchesi as part of his forthcoming nance and now in the Ashmolean Museum larger study of the Sumerian king lists. (Langdon 1923 pl. 6) No. -

Urnamma of Ur in Sumerian Literary Tradition

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 1999 Urnamma of Ur in Sumerian Literary Tradition Flückiger-Hawker, Esther Abstract: This book presents new standard editions of all the hitherto known hymns of Urnamma, the founder of the Third Dynasty of Ur (fl. 2100 B.C.), and adds new perspectives to the compositions and development of the genre of Sumerian royal hymns in general. The first chapter (I) is introductory in nature (historical background, the reading of the name Urnamma, Sumerian royal hymns). The second chapter (II) presents a general survey of Urnamma’s hymnic corpus, including arguments for a broader definition of Sumerian royal hymns and an attempt at classifying the non-standard orthography found in Urnamma’s hymns. The third chapter (III) deals with correlations of Urnamma’s hymns with other textual sources pertaining to him. A fourth chapter (IV) is devoted to aspects of continuity and change in royal hymnography by analyzing the Urnamma hymns in relation to other royal hymns and related genres. A discussion of topoi of legitimation and kingship and narrative materials in different text types during different periods of time and other findings concerning statues, stelas and royal hymns addnew perspectives to the ongoing discussion of the original setting of royal hymns. Also, reasons are given why a version of the Sumerian King List may well be dated to Urnamma and the thesis advanced that Išmēdagan of Isin was not only an imitator of Šulgi but also of Urnamma. The final of the chapter IV shows that Urnamma A, also known as Urnamma’s Death, uses the language of lamentation literature and Curse of Agade which describe the destruction of cities, and applies it to the death of a king. -

Mesopotamian Art First Term 1959

Mesopotamian Art First term 1959 Civilization (‘urban society’), as I said last Thursday, began somewhat earlier in Ancient Mesopotamia than in Egypt. Let us begin by looking at a map of the region. The first settlers in Mesopotamia, the land of the two rivers, appear to have come from the Persian Highlands to the east, those who settled in the marshlands of the Tigris-Euphrates delta developed an urban economy which was at all times more decentralized than Egypt’s—the local towns always retaining a large measure of autonomy in their own affairs. These first settlers were united by a common culture as expressed in the buildings and sculpture, but not by a common language: for Sumerian was spoken in [south Sumer] and Akkadian, a Semitic language in the north. To the west of the Mesopotamia is the Arabian desert, to the north the plains of Syria, and to the north and north-east the Armenian and the Persian Highlands. Note the positions of Al-Ubaid, Ur, Eridu and Larsa situated in southern Mesopotamia, the ancient Sumer. They were at that time quite close to the shores of the Persian Gulf— for the delta of the river has been built up considerably in the past 5,000 years. To the north of Sumer, was Akkad, with such towns as Khafaje, Tell Asmar, Babylon and Tell Agrab. And further to the north were Tel Halaf, Tel Brak, Nineveh, Assur, Tepe Gawra and Samara. Mari was in the extreme west of the cultural area, Susa in the extreme East. The earliest settlement in the region occurred in the north. -

71. Genesis Unleashed

October 10, 2020 Genesis Proclaimed Association www.genesisproclaimed.org Email: [email protected] Genesis Unleashed Dick Fischer Enough archaeological artifacts and pieces of literature have been recovered from the ancient Near East in recent years touching on Genesis characters and events to highlight the need for making necessary English translation adjustments to the sacred text. Rooted in the 1611 King James Version, Genesis has blossomed into puzzling modern versions to keep us perplexed even today. Just a cursory reading of the Genesis 2-11 narrative places early patriarchal history within the context of the Neolithic Period in southern Mesopotamia, present-day Iraq, beginning no earlier than 7,000 years ago, whereas our species has occupied earthly domains for hundreds of thousands of years. Old Testament commentators have shown some awareness of ancient Near East literature in recent years, but typically do not dig deep enough to recognize its value. If these much-maligned chapters of Genesis are translated and understood as Adamic/Semitic history, not as human history, they make perfectly good sense. Only the King James Version is examined here, but the principles apply to all translations. Keywords: Genesis, Adam, Adam and Eve, Seth, Cain, Enoch, Noah, Flood, Sumerians, Akkadians, Eridu, Mesopotamia, Near East, Tigris, Euphrates, Ziusudra, Gilgamesh, Sumerian King List, Adapa. Where Did We Go Wrong? Interpretational mistakes with major long-term consequences began with the early Christian Church. When the Apostle Paul set out on missionary trips he visited synagogues seeking out Jews who would listen to the good news the Messiah had come. Considering Jesus to be God in human form was considered blasphemous to many of his Jewish listeners, yet Paul found a few who took his message to heart. -

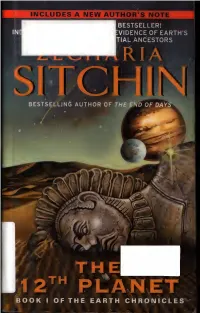

THE 12Th PLANET the STAIRWAY to HEAVEN the WARS of GODS and MEN the LOST REALMS WHEN TIME BEGAN the COSMIC CODE

INCLUDES A NEW AUTHOR'S P BESTSELLER! EVIDENCE OF EARTH’S TIAL ANCESTORS HARPER Now available in hardcover: U.S. $7.99 CAN. $8.99 THE LONG-AWAITED CONCLUSION TO ZECHARIA SITCHIN’s GROUNDBREAKING SERIES THE EARTH CHRONICLES ZECHARIA SITCHIN THE END DAYS Armageddon and Propfiffie.t of tlic Renirn . Available in paperback: THE EARTH CHRONICLES THE 12th PLANET THE STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN THE WARS OF GODS AND MEN THE LOST REALMS WHEN TIME BEGAN THE COSMIC CODE And the companion volumes: GENESIS REVISITED EAN DIVINE ENCOUNTERS . “ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT BOOKS ON EARTH’S ROOTS EVER WRITTEN.” East-West Magazine • How did the Nefilim— gold-seekers from a distant, alien planet— use cloning to create beings in their own image on Earth? •Why did these "gods" seek the destruc- tion of humankind through the Great Flood 13,000 years ago? •What happens when their planet returns to Earth's vicinity every thirty-six centuries? • Do Bible and Science conflict? •Are were alone? THE 12th PLANET "Heavyweight scholarship . For thousands of years priests, poets, and scientists have tried to explain how life began . Now a recognized scholar has come forth with a theory that is the most astonishing of all." United Press International SEP 2003 Avon Books by Zecharia Sitchin THE EARTH CHRONICLES Book I: The 12th Planet Book II: The Stairway to Heaven Book III: The Wars of Gods and Men Book IV: The Lost Realms Book V: When Time Began Book VI: The Cosmic Code Book VII: The End of Days Divine Encounters Genesis Revisited ATTENTION: ORGANIZATIONS AND CORPORATIONS Most Avon Books paperbacks are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchases for sales promotions, premiums, or fund-raising. -

Summer and Akkad Geographical Context the Fertile Crescent Ubaid Culture

Summer and Akkad Geographical Context The Fertile Crescent Ubaid Culture • Roughly 6000 – 3500 BC. • First pottery • First settled ‘towns’ • “The creators of the Ubaid… were heirs to cumulative developments in the long history of agricultural village life in the Near East” (Hout 1992, 188). Sumerians Arrived from Asia ca 3900 – 3500 Unique language that resembles Turkic and Hungarian • Brought (?) Copper tech. • Applied to irrigation • Kish or Uruk earliest city • Competing city states • Legend of the Flood • Legends of divine parentage Sumer Kuhrt • Kuhrt, Amelie. 1995. The Ancient Near East. • Cultural parallelism • Semitic words in Sumerian texts • Diversity of land ownership • Monarchy more than theocracy • Contra Edgar et al. City Rivalries • Eannatum, king of Lagash • Ca. 2450 BC • Conquered the cities of Sumer • Vulture Stele commemorates victory over Enakalle of Umma The Vulture Stele The Vulture Stele • Winter, Irene. 1985. After the Battle is Over: The “Stele of the Vultures” and the Beninning of Historical Narrative in the Art of the Ancient Near East. Studies in the History of Art 16, Symposium Papers IV: Pictoral Narrative in Antiquity and the Middle Ages: 11 – 32. Sargon of Akkad (Agade) • Lugalzagesi • Ruler of Uruk • Hegemon of Sumerian empire • Sargon • Ruler of Akkad (2296 - 2240) • Semitic • Begins a literary tradition of pasts remembered (recreated). The Dynasty of Sargon • Sargon (2296 -2240) • Rimush (2239 – 2230) • Manishtushu (2229 – 2214) • Naram Sin (2213 – 2176) • Sharkalisharri (2175 – 2150) • …but these dates are disputed Ur – The Sumerian Renaissence • Utuhegal (2119 – 2113) • Ur-Nammu (2112 – 2095) • Shulgi (2094 – 2047) • Amar –Sin (2046 – 2038) • Shu-Sin (2037 – 2027) • Ibbi-Sin (2026 – 2004) Material Record Cylinder Seals Cuneiform Bronze • Ca.