Torres Strait and Dawdhay: Dimensions of Self and Otherness on Yam Island I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

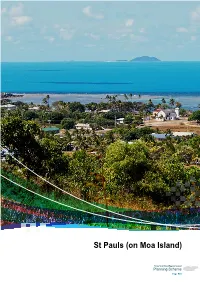

St Pauls (On Moa Island) - Local Plan Code

7.2.13 St Pauls (on Moa Island) - local plan code Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) St Pauls (on Moa Island) Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 523 Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 524 Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) Papua New Guinea Saibai Ugar Boigu Stephen Island Erub Dauan Darnley Island Masig Yorke Island Iama Mabuyag Yam Island Mer Poruma Murray Island Coconut Island Badu Kubin Moa SStt PPaulsauls Warraber Sue Island Keriri Hammond Island Mainland Australia Mainland Australia Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 525 Editor’s Note – Community Snapshot Location Topography and Environment • St Pauls is located on the eastern side of Moa • Moa Island, like other islands in the group, is Island, which is part of the Torres Strait inner and a submerged remnant of the Great Dividing near western group of islands. St Paul’s nearest Range, now separated by sea. The island neighbour is Kubin, which is located on the comprises of largely of rugged, open forest and south-western side of Moa Island. Approximately is approximately 17km in diameter at its widest 15km from the outskirts of St Pauls. point. • Native flora and fauna that have been identified Population near St Pauls include fawn leaf nosed bat, • According to the most recent census, there were grey goshawk, emerald monitor, little tern, 258 people living in St Pauls as at August 2011, red goshawk, radjah shelduck, lipidodactylus however, the population is highly transient and primilus, bare backed fruit bat, torresian tube- this may not be an accurate estimate. -

How Torres Strait Islanders Shaped Australia's Border

11 ‘ESSENTIALLY SEA‑GOING PEOPLE’1 How Torres Strait Islanders shaped Australia’s border Tim Rowse As an Opposition member of parliament in the 1950s and 1960s, Gough Whitlam took a keen interest in Australia’s responsibilities, under the United Nations’ mandate, to develop the Territory of Papua New Guinea until it became a self-determining nation. In a chapter titled ‘International Affairs’, Whitlam proudly recalled his government’s steps towards Papua New Guinea’s independence (declared and recognised on 16 September 1975).2 However, Australia’s relationship with Papua New Guinea in the 1970s could also have been discussed by Whitlam under the heading ‘Indigenous Affairs’ because from 1973 Torres Strait Islanders demanded (and were accorded) a voice in designing the border between Australia and Papua New Guinea. Whitlam’s framing of the border issue as ‘international’, to the neglect of its domestic Indigenous dimension, is an instance of history being written in what Tracey Banivanua- Mar has called an ‘imperial’ mode. Historians, she argues, should ask to what extent decolonisation was merely an ‘imperial’ project: did ‘decolonisation’ not also enable the mobilisation of Indigenous ‘peoples’ to become self-determining in their relationships with other Indigenous 1 H. C. Coombs to Minister for Aboriginal Affairs (Gordon Bryant), 11 April 1973, cited in Dexter, Pandora’s Box, 355. 2 Whitlam, The Whitlam Government, 4, 10, 26, 72, 115, 154, 738. 247 INDIGENOUS SELF-determinatiON IN AUSTRALIA peoples?3 This is what the Torres Strait Islanders did when they asserted their political interests during the negotiation of the Australia–Papua New Guinea border, though you will not learn this from Whitlam’s ‘imperial’ account. -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

Card Operated Meter Information

Purchasing a power card for your card-operated meter Power cards are available from the following sales outlets: Community Retail Agent Address Arkai (Kubin) Community T.S.I.R.C. - Kubin KUBIN COMMUNITY, MOA ISLAND QLD 4875 Arkai (Kubin) Community CEQ - Kubin IKILGAU YABY RD, KUBIN VILLAGE, MOA ISLAND QLD 4875 Aurukun Island & Cape 39 KANG KANG RD, AURUKUN QLD 4892 Aurukun Supermarket Aurukun Kang Kang Café 502 KANG KAND RD, AURUKUN QLD 4892 Badu (Mulgrave) Island Badu Hotel 199 NONA ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Badu (Mulgrave) Island Island & Cape Badu MAIRU ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Supermarket (Bottom Shop) Badu (Mulgrave) Island J & J Supermarket 341 CHAPMAN ST, BADU ISLAND QLD (Top Shop) 4875 Badu (Mulgrave) Island T.S.I.R.C. - Badu NONA ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Bamaga Bamaga BP Service AIRPORT RD, BAMAGA QLD 4876 Station Bamaga Cape York Traders 201 LUI ST, BAMAGA QLD 4876 – Bamaga Store Bamaga CEQ – Bamaga 105 ADIDI AT, BAMAGA QLD 4876 Supermarket Boigu (Talbot) Island CEQ – Boigu TOBY ST, BOIGU QLD 4875 Supermarket Boigu (Talbot) Island T.S.I.R.C. - Boigu 66 CHAMBERS ST, BOIGU ISLAND QLD 4875 Darnley Island (Erub) Daido Tavern PILOT ST, DARNLEY ISLAND QLD 4875 Darnley Island (Erub) T.S.I.R.C. - Darnley COUNCIL OFFICE, DARNLEY ISLAND QLD 4875 Dauan Island (Mt CEQ - Dauan MAIN ST, DAUAN ISLAND QLD 4875 Cornwallis) Supermarket Dauan Island (Mt T.S.I.R.C. - Dauan COUNCIL OFFICE, MAIN ST, DAUAN Cornwallis) ISLAND QLD 4875 Doomadgee CEQ – Doomadgee 266 GUNNALUNJA DR, DOOMADGEE QLD Supermarket 4830 Doomadgee Doomadgee 1 GOODEEDAWA RD, DOOMADGEE -

Part 7 Transport Infrastructure Plan

Sea Transport Safety The marine investigation unit of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) was contacted for information pertaining to recent accidents and incidents with large trading vessels in the region. The data provided related to five incidents that occurred after July 1995 and before 2004: a) A man overboard from the vessel Murshidabad in 1996; b) A close quarters situation between the Maersk Taupo and a small dive runabout off Ackers Shoal Beacon in 1997; c) The grounding of the vessel Thebes on Larpent Bank in 1997; d) The grounding of the vessel Dakshineshwar on Larpent Bank in 1997; and e) The grounding of the vessel NOL Amber on Larpent Bank in 1997. Figure 3.7 shows the location of marine accidents that have occurred in northern Queensland in 2004. Figure 3.7 Location of Marine Accidents in Northern Queensland (2004) Source: MSQ: 2005 Torres Strait Transport Infrastructure Plan - Integrated Strategy Report J:\mmpl\10303705\Engineering\Reports\Transport Infrastructure Plan\Transport Infrastructure Plan - Rev I.doc Revision I November 2006 Page 21 Figure 3.8 Existing Ferry Services Torres Strait Transport Ugar (Stephen) Island Infrastructure Plan Papua New Guinea Ferry Routes ° Saibai (Kaumag) Island Dauan Island Erub (Darnley) Island Map 1 - Saibai (Kaumag) Island to Dauan Island 1:200,000 Map 2 - Ugar (Stephen) Island to Erub (Darnley) Island 1:150,000 Hammond Waiben Map 1 Island (Thursday) Island Map 2 Nguruppai (Horn) Island Muralug (Prince of Wales) Island Map 3 Seisia Seisia Map 3 - Thursday Island 1:300,000 -

1998 ANNUAL REPORT 60011 Cover 16/11/98 2:43 PM Page 2

TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY 1997~1998 ANNUAL REPORT 60011 Cover 16/11/98 2:43 PM Page 2 ©Commonwealth of Australia 1998 ISSN 1324–163X This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the Public Affairs Officer, TSRA, PO Box 261, Thursday Island, Queensland 4875. The artwork on the front cover was designed by Torres Strait Islander artist, Alick Tipoti. Annual Report 1997~98 PUPUA NEW GUINEA SAIBAI ISLAND (Kaumag Is) BOIGU ISLAND UGAR (STEPHEN) ISLAND DAUAN ISLAND TORRES STRAIT DARNLEY ISLAND YAM ISLAND MASIG (YORKE) ISLAND MABUIAG ISLAND MER (MURRAY) ISLAND BADU ISLAND PORUMA (COCONUT) ISLAND ST PAULS WARRABER (SUE) ISLAND KUBIN MOA ISLAND HAMMOND ISLAND THURSDAY ISLAND (Port Kennedy, Tamwoy) HORN ISLAND PRINCE OF WALES ISLAND SEISIA BAMAGA CAPE YORK TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY © Commonwealth of Australia 1998 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the Public Affairs Officer, TSRA, PO Box 261, Thursday Island, Queensland 4875. The artwork on the front cover was designed by Torres Strait Islander artist, Alick Tipoti. TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY Senator the Hon. John Herron Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Suite MF44 Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister In accordance with section 144ZB of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission Act 1989, I am delighted to present you with the fourth Annual Report of the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). -

Saibai Island - Local Plan Code

7.2.12 Saibai Island - local plan code Part 7: Local Plans Saibai Island Saibai Island Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 499 Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 500 Part 7: Local Plans Saibai Island Papua New Guinea Saibai Ugar Boigu Stephen Island Erub Dauan Darnley Island Masig Yorke Island Iama Mabuyag Yam Island Mer Poruma Murray Island Coconut Island Badu Kubin Moa St Pauls Warraber Sue Island Keriri Hammond Island Mainland Australia Mainland Australia Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 501 Editor’s Note – Community Snapshot Location • Due to the topography and low lying nature of the island, other hazards such as catchment flooding • Saibai Island is part of the Torres Strait top and landslide do not present a significant threat western group of islands. Located approximately to the Saibai Island community. 3km south of Papua New Guinea and 138km north of Horn Island, Saibai is the second most • Most of the larger vegetated areas are identified northern point of Australia. As such, it plays as a potential bushfire risk. a significant role in national border security and serves as an early detection zone for the Topography and Environment transmission of exotic pests and diseases into mainland Australia. • Saibai is a flat, mud island with large interior swamps filled with brackish water. Its origins stem from the presence of the Fly River that Population discharges vast quantities of silt and sediment • According to the most recent census, there were into nearby coastal waters. 480 people living on Saibai Island in August 2011, however, the population is highly transient • Covering an area of 10,400 hectares, it is one of and this may not be an accurate estimate. -

Iama (Yam) Island - Local Plan Code

7.2.5 Iama (Yam) Island - local plan code Part 7: Local Plans Iama (Yam) Island Iama (Yam) Island Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 317 Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 318 Part 7: Local Plans Iama (Yam) Island Papua New Guinea Saibai Ugar Boigu Stephen Island Erub Dauan Darnley Island Masig Yorke Island Iama Mabuyag Yam Island Mer Poruma Murray Island Coconut Island Badu Kubin Moa St Pauls Warraber Sue Island Keriri Hammond Island Mainland Australia Mainland Australia Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 319 Editor’s Note – Community Snapshot Location Topography and Environment • Iama Island is part of the Torres Strait central • Iama Island is a vegetated granite island fringed group of islands. The island is positioned roughly with coral sand flats. The island landforms are in the centre of the region, approximately 93km distinguished by three distinct types: vegetated, north east of Horn Island. steep and hilly land; plateau areas at the top of the slope; and flat areas around the coastline. Population • Dominant habitat types include mangrove • According to the most recent census, there were forests, vine forests and the coastal environment. 315 people living on Iama Island in August 2011, The mangroves and coastal habitats in particular however, the population is highly transient and are of very high quality, with the latter providing this may not be an accurate estimate. habitat for rare and threatened bird species. In addition, the sea grasses in surrounding waters Natural Hazards provide important dugong habitat. • The township, along with the airstrip, • There are many watercourses on Iama Island, telecommunications and waste infrastructure, is many that only flow during the wet season. -

On Moa Island) - Local Plan Code

7.2.7 Kubin (on Moa Island) - local plan code Part 7: Local Plans Kubin (on Moa Island) Kubin (on Moa Island) Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 371 Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 372 Part 7: Local Plans Kubin (on Moa Island) Papua New Guinea Saibai Ugar Boigu Stephen Island Erub Dauan Darnley Island Masig Yorke Island Iama Mabuyag Yam Island Mer Poruma Murray Island Coconut Island Badu KubinKubin Moa St Pauls Warraber Sue Island Keriri Hammond Island Mainland Australia Mainland Australia Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 373 Editor’s Note – Community Snapshot Location Topography and Environment • Kubin is located on the south-western side of • Moa Island, like other islands in the group, is Moa Island, which is part of the Torres Strait a submerged remnant of the Great Dividing inner and near western group of islands. Kubin’s Range now separated by sea. The island nearest neighbour is St Pauls, located on the comprises of largely of rugged, open forest and eastern side of Moa Island, approximately 15km is approximately 17km in diameter at its widest from the outskirts of Kubin. point. • Moa Peak on the north eastern side of the island Population is the highest point in the Torres Strait Regional • According to the most recent census, there were Island Council. 163 people living in Kubin as at August 2011, however, the population is highly transient and • Native flora and fauna that have been identified this may not be an accurate estimate. on Kubin Island include fawn leaf nosed bat, grey goshawk, emerald monitor, little tern, red goshawk, radjah shelduck, lipidodastylus Natural Hazards pumilus, bare backed fruit back, torresian tube- • Coastal hazards, including erosion and storm nosed bat, emoia atrostata, eastern curlew, tide inundation, have an impact on a few low beach stone curlew, coastal sheatail bat. -

A Novel Approach to Tradition: Torres Strait Islanders and Ion Idriess

A Novel Approach to Tradition: Torres Strait Islanders and Ion Idriess Maureen Fuary Anthropology and Archaeology James Cook University This paper considers the significance of the novel Drums of Mer (1941) in contemporary Torres Strait Islanders’ lives. Its use as narrative by many Islanders today constitutes one means by which men especially have come to know themselves, white others, and their past. In particular, I explore the ways in which this story appeals to and is appealed to by Yam Island people. Contrary to literary deconstmctions of Idriess’s representations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, my paper argues that in seriously attending to Torres Strait readings of Drums of Mer we can see that for contemporary Islander readers, it is not themselves who are other but rather the white protagonists. I employ Said’s (1994) notion of ‘cultural overlap’ and de Certeau’s (1988) understandings of reading and writing as ‘everyday practices’ to frame my analysis of the differing impacts of the historical novel, Drums of Mer, and the Reports of the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Torres Straits. It is through story telling that Yam Island selves are placed in the past and the present, and in Idriess’s memorable story a similar effect is achieved. In his novel approach, the past becomes his-story, a romanticised refraction of the Reports. Unlike the Reports, this novel is a sensual rendering of a Torres Strait past, and at this level it operates as a mnemonic device for Yam Island people, triggering memories and the imagination through the senses. This Torres Strait Islander detour by way of a past via a story, can be understood as a means by which Yam Island people continue to actively produce powerful images of themselves, for both themselves and for others. -

Native Affairs

NATIVE AFFAIRS. Information contained in Report of Director of Native Affairs for the Twelve Months ended 30th June, 1958. Digitised by AIATSIS Library 2007, RS 25.4/3 - www.aiatsis.gov.au/library BOIGU IS.A .SAIBAI IS. DAUAN IS.A YAM>DARNLEY.IS. MABUIAG ISA *J5- ^ffiL^v .c ^ CONUT IS. ;BAMAGA TLEMENT .OCKHART RIVER MISSION Location of Government Settlements, Church Missions and Torres Strait Island Reserves shown • For population figures and other statistics see opposite page Digitised by AIATSIS Library 2007, RS 25.4/3 - www.aiatsis.gov.au/library Native Affairs—Annual Report of Director of Native Affairs for the Year ended 30th June, 1958. SIR,—I have the honour to submit the Annual There are four Government Settlements and Report under "The Aboriginals' Preservation thirteen Church Missions and one Government and Protection Acts, 1939 to 1946," and "The Hostel in Queensland. During the year realign Torres Strait Islanders' Acts, 1939 to 1946," for ment of boundaries of Reserves caused the the year ended 30th June, 1958. following alterations in areas:— Queensland's population of controlled and Mapoon Mission.—2,140,800 acres to 1,353,600 acres—reduction 787,200 acres. non-controlled aboriginals, half bloods and Torres Strait Islanders is indicated in the Weipa Mission.—1,600,000 acres to 876,800 acres— reduction 723,200 acres. "* following table:— Aurukun Mission.—1,216,000 acres to 793,600 acres Aboriginals— —reduction 422,400 acres. Controlled 9,960 Non-Controlled .. 1,000 Edward River Mission—554,880 acres to 1,152,000 10,960 acres—increase 597,120 acres. -

Medical Officer Opportunities ACKNOWLEDGEMENT of TRADITIONAL OWNERS

Medical Officer opportunities ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF TRADITIONAL OWNERS The Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners / Custodians, past and present, within the lands in which we work. CAPE YORK Ayabadhu, Alngith, Anathangayth, Anggamudi, Apalech, Binthi, Burunga, Dingaal, Girramay, Gulaal, Gugu Muminh, Guugu-Yimidhirr, Kaantju, Koko-bera, Kokomini, Kuku Thaypan, Kuku Yalanji, Kunjen/Olkol, Kuuku – Yani, Lama Lama, Mpalitjanh, Munghan, Ngaatha, Ngayimburr, Ngurrumungu, Nugal, Oolkoloo, Oompala, Peppan, Puutch, Sara, Teppathiggi, Thaayorre, Thanakwithi, Thiitharr, Thuubi, Tjungundji, Uutaalnganu, Wanam, Warrangku, Wathayn, Waya, Wik, Wik Mungkan, Wimarangga, Winchanam, Wuthathi and Yupungathi. NORTHERN PENINSULA AREA Atambaya, Gudang, Yadhaykenu, Angkamuthi, Wuthathi. TORRES STRAIT ISLANDS The five tribal nations of the Torres Strait Islands: The Kaiwalagal The Maluilgal The Gudamaluilgal The Meriam The Kulkalgal Nations. RECOGNITION OF AUSTRALIAN SOUTH SEA ISLANDERS Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service formally recognises the Australian South Sea Islanders as a distinct cultural group within our geographical boundaries. Torres and Cape HHS is committed to fulfilling the Queensland Government Recognition Statement for Australian South Sea Islander Community to ensure that present and future generations of Australian South Sea Islanders have equality of opportunity to participate in and contribute to the economic, social, political and cultural life of the State. Aboriginal and Torres