Cultural Heritage Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weipa Community Plan 2012-2022 a Community Plan by the Weipa Community for the Weipa Community 2 WEIPA COMMUNITY PLAN 2012-2022 Community Plan for Weipa

Weipa Community Plan 2012-2022 A Community Plan by the Weipa Community for the Weipa Community 2 WEIPA COMMUNITY PLAN 2012-2022 Our Community Plan ..................................... 4 The history of Weipa ...................................... 6 Weipa today .................................................... 7 Challenges of today, opportunities for tomorrow .................................................... 9 Some of our key challenges are inter-related ............................................ 10 Contents Our children are our future ..........................11 Long term aspirations .................................. 13 “This is the first Our economic future .....................................14 Community Plan for Weipa. Our community ............................................. 18 Our environment ......................................... 23 It is our plan for the future Our governance ............................................. 26 Implementation of our of our town.” Community Plan .......................................... 30 WEIPA COMMUNITY PLAN 2012-2022 3 Our Community Plan This is the first Community Plan for Weipa. It is our plan How was it developed? This Community Plan was An important part of the community engagement process for the future of our town. Our Community Plan helps us developed through a number of stages. was the opportunity for government agencies to provide address the following questions: input into the process. As Weipa also has an important role Firstly, detailed research was undertaken of Weipa’s in the Cape, feedback was also sought from the adjoining • What are the priorities for Weipa in the next 10 years? demographics, economy, environment and governance Councils of Napranum, Mapoon, Aurukun and Cook Shires. structures. Every previous report or study on the Weipa • How do we identify and address the challenges region was analysed to identify key issues and trends. This Community Plan has been adopted by the Weipa Town that we face? Authority on behalf of the Weipa Community. -

Your Great Barrier Reef

Your Great Barrier Reef A masterpiece should be on display but this one hides its splendour under a tropical sea. Here’s how to really immerse yourself in one of the seven wonders of the world. Yep, you’re going to get wet. southern side; and Little Pumpkin looking over its big brother’s shoulder from the east. The solar panels, wind turbines and rainwater tanks that power and quench this island are hidden from view. And the beach shacks are illusory, for though Pumpkin Island has been used by families and fishermen since 1964, it has been recently reimagined by managers Wayne and Laureth Rumble as a stylish, eco- conscious island escape. The couple has incorporated all the elements of a casual beach holiday – troughs in which to rinse your sandy feet, barbecues on which to grill freshly caught fish and shucking knives for easy dislodgement of oysters from the nearby rocks – without sacrificing any modern comforts. Pumpkin Island’s seven self-catering cottages and bungalows (accommodating up to six people) are distinguished from one another by unique decorative touches: candy-striped deckchairs slung from hooks on a distressed weatherboard wall; linen bedclothes in this cottage, waffle-weave in that; mint-green accents here, blue over there. A pair of legs dangles from one (Clockwise from top left) Book The theme is expanded with – someone has fallen into a deep Pebble Point cottage for the unobtrusively elegant touches, afternoon sleep. private deck pool; “self-catering” such as the driftwood towel rails The island’s accommodation courtesy of The Waterline and the pottery water filters in is self-catering so we arrive restaurant; accommodations Pumpkin Island In summer the caterpillars Feel like you’re marooned on an just the right shade of blue. -

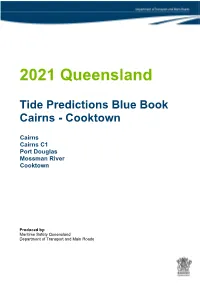

Bluebook-2021 Cairns

2021 Queensland Tide Predictions Blue Book Cairns - Cooktown Cairns Cairns C1 Port Douglas Mossman River Cooktown Produced by: Maritime Safety Queensland Department of Transport and Main Roads Copyright and disclaimer This work is licensed under a creative Commons Attribute 4.0 Australia licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ © The State of Queensland (Department of Transport and Main Roads) 2020 Tide station data for tide predictions is collected by the Department of Transport and Main Roads (Maritime Safety Queensland); Queensland port authorities and corporations; the Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts; the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (Leggatt Island) and the Australian Hydrographic Service (Bugatti Reef). The Queensland Tide Tables publication is comprised of tide prediction tables from the Bureau of Meteorology and additional information provided by Maritime Safety Queensland. The tidal prediction tables are provided by the National Tidal Centre, Bureau of Meteorology. Copyright of the tidal prediction tables is vested in the Commonwealth of Australia represented by the National Tidal Centre, Bureau of Meteorology. The Bureau of Meteorology gives no warranty of any kind whether express, implied, statutory or otherwise in respect to the availability, accuracy, currency, completeness, quality or reliability of the information or that the information will be fit for any particular purpose or will not infringe any third party Intellectual Property rights. The Bureau's liability for any loss, damage, cost or expense resulting from use of, or reliance on, the information is entirely excluded. Information in addition to the tide prediction tables is provided by the Department of Transport and Main Roads (Maritime Safety Queensland). -

St Pauls (On Moa Island) - Local Plan Code

7.2.13 St Pauls (on Moa Island) - local plan code Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) St Pauls (on Moa Island) Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 523 Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 524 Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) Papua New Guinea Saibai Ugar Boigu Stephen Island Erub Dauan Darnley Island Masig Yorke Island Iama Mabuyag Yam Island Mer Poruma Murray Island Coconut Island Badu Kubin Moa SStt PPaulsauls Warraber Sue Island Keriri Hammond Island Mainland Australia Mainland Australia Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 525 Editor’s Note – Community Snapshot Location Topography and Environment • St Pauls is located on the eastern side of Moa • Moa Island, like other islands in the group, is Island, which is part of the Torres Strait inner and a submerged remnant of the Great Dividing near western group of islands. St Paul’s nearest Range, now separated by sea. The island neighbour is Kubin, which is located on the comprises of largely of rugged, open forest and south-western side of Moa Island. Approximately is approximately 17km in diameter at its widest 15km from the outskirts of St Pauls. point. • Native flora and fauna that have been identified Population near St Pauls include fawn leaf nosed bat, • According to the most recent census, there were grey goshawk, emerald monitor, little tern, 258 people living in St Pauls as at August 2011, red goshawk, radjah shelduck, lipidodactylus however, the population is highly transient and primilus, bare backed fruit bat, torresian tube- this may not be an accurate estimate. -

Part 16 Transport Infrastructure Plan

Figure 7.3 Option D – Rail Line from Cairns to Bamaga Torres Strait Transport Infrastructure Plan Masig (Yorke) Island Option D - Rail Line from Cairns to Bamaga Major Roads Moa Island Proposed Railway St Pauls Kubin Waiben (Thursday) Island ° 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 Kilometres Seisia Bamaga Ferry and passenger services as per current arrangements. DaymanPoint Shelburne Mapoon Wenlock Weipa Archer River Coen Yarraden Dixie Cooktown Maramie Cairns Normanton File: J:\mmpl\10303705\Engineering\Mapping\ArcGIS\Workspaces\Option D - Rail Line.mxd 29.07.05 Source of Base Map: MapData Sciences Pty Ltd Source for Base Map: MapData Sciences Pty Ltd 7.5 Option E – Option A with Additional Improvements This option retains the existing services currently operating in the Torres Strait (as per Option A), however it includes additional improvements to the connections between Horn Island and Thursday Island. Two options have been strategically considered for this connection: Torres Strait Transport Infrastructure Plan - Integrated Strategy Report J:\mmpl\10303705\Engineering\Reports\Transport Infrastructure Plan\Transport Infrastructure Plan - Rev I.doc Revision I November 2006 Page 91 • Improved ferry connections; and • Roll-on roll-of ferry. Improved ferry connections This improvement considers the combined freight and passenger services between Cairns, Bamaga and Thursday Island, with a connecting ferry service to OSTI communities. Possible improvements could include co-ordinating fares, ticketing and information services, and also improving safety, frequency and the cost of services. Roll-on roll-off ferry A roll-on roll-off operation between Thursday Island and Horn Island would provide significant benefits in moving people, cargo, and vehicles between the islands. -

How Torres Strait Islanders Shaped Australia's Border

11 ‘ESSENTIALLY SEA‑GOING PEOPLE’1 How Torres Strait Islanders shaped Australia’s border Tim Rowse As an Opposition member of parliament in the 1950s and 1960s, Gough Whitlam took a keen interest in Australia’s responsibilities, under the United Nations’ mandate, to develop the Territory of Papua New Guinea until it became a self-determining nation. In a chapter titled ‘International Affairs’, Whitlam proudly recalled his government’s steps towards Papua New Guinea’s independence (declared and recognised on 16 September 1975).2 However, Australia’s relationship with Papua New Guinea in the 1970s could also have been discussed by Whitlam under the heading ‘Indigenous Affairs’ because from 1973 Torres Strait Islanders demanded (and were accorded) a voice in designing the border between Australia and Papua New Guinea. Whitlam’s framing of the border issue as ‘international’, to the neglect of its domestic Indigenous dimension, is an instance of history being written in what Tracey Banivanua- Mar has called an ‘imperial’ mode. Historians, she argues, should ask to what extent decolonisation was merely an ‘imperial’ project: did ‘decolonisation’ not also enable the mobilisation of Indigenous ‘peoples’ to become self-determining in their relationships with other Indigenous 1 H. C. Coombs to Minister for Aboriginal Affairs (Gordon Bryant), 11 April 1973, cited in Dexter, Pandora’s Box, 355. 2 Whitlam, The Whitlam Government, 4, 10, 26, 72, 115, 154, 738. 247 INDIGENOUS SELF-determinatiON IN AUSTRALIA peoples?3 This is what the Torres Strait Islanders did when they asserted their political interests during the negotiation of the Australia–Papua New Guinea border, though you will not learn this from Whitlam’s ‘imperial’ account. -

Torres Strait Regional Economic Investment Strategy, 2015-2018 Phase 1: Regional Business Development Strategy

Page 1 Torres Strait Regional Economic Investment Strategy, 2015-2018 Phase 1: Regional Business Development Strategy A Framework for Facilitating Commercially-viable Business Opportunities in the Torres Strait September 2015 Page 2 This report has been prepared on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). It has been prepared by: SC Lennon & Associates Pty Ltd ACN 109 471 936 ABN 74 716 136 132 PO Box 45 The Gap Queensland 4061 p: (07) 3312 2375 m: 0410 550 272 e: [email protected] w: www.sashalennon.com.au and Workplace Edge Pty Ltd PO Box 437 Clayfield Queensland 4011 p (07) 3831 7767 m 0408 456 632 e: [email protected] w: www.workplaceedge.com.au Disclaimer This report was prepared by SC Lennon & Associates Pty Ltd and Workplace Edge Pty Ltd on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). It has been prepared on the understanding that users exercise their own skill and care with respect to its use and interpretation. Any representation, statement, opinion or advice expressed or implied in this publication is made in good faith. SC Lennon & Associates Pty Ltd, Workplace Edge Pty Ltd and the authors of this report are not liable to any person or entity taking or not taking action in respect of any representation, statement, opinion or advice referred to above. Photo image sources: © SC Lennon & Associates Pty Ltd Page 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A New Approach to Enterprise Assistance in the Torres Strait i A Plan of Action i Recognising the Torres Strait Region’s Unique Challenges ii -

Kuranda Scenic Railway Brochure

Kuranda Scenic Railway 2021 / 22 KURANDA Skyrail Kuranda RAILWAY STATION EXPERIENCE KURANDA SCENIC RAILWAY Terminal Port Douglas and Choose to experience your journey in either Heritage Class or Gold Class – both offering stunning views and old-time charm Koala Gardens Rainforestation Northern Beaches in refurbished wooden heritage carriages. As you reach Kuranda, spend your day strolling through the picturesque village and Australian Butterfly enjoy restaurants, shops, markets, and activities at your own pace, or combine your trip with a Kuranda day tour package. Sanctuary coral sea Birdworld Barron Skyrail Kuranda Markets Falls red Smithfield HERITAGE CLASS EXPERIENCE* GOLD CLASS EXPERIENCE* Stop peak Terminal Travel in the Kuranda Scenic Railway original timber carriages, Enjoy the comfort of Gold Class in carriages adorned in rob’s monument some of which are up to 100 years old, and experience the handcrafted Victorian inspired décor, club lounge style pioneering history as the train winds its way through World seating and personal onboard service. Heritage-listed rainforest. lake Your Gold Class journey includes: placid FRESHWATER Your Heritage Class journey includes: • Souvenir trip guide and gift pack falls lookout RAILWAY STATION Cairns • Souvenir trip guide available in nine languages • Audio commentary Airport • Audio commentary • Brief photographic stop at Barron Falls viewing platform • Brief photographic stop at Barron Falls viewing platform • Welcome drink^ and all-inclusive locally sourced appetisers stoney creek falls • Filtered -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

Card Operated Meter Information

Purchasing a power card for your card-operated meter Power cards are available from the following sales outlets: Community Retail Agent Address Arkai (Kubin) Community T.S.I.R.C. - Kubin KUBIN COMMUNITY, MOA ISLAND QLD 4875 Arkai (Kubin) Community CEQ - Kubin IKILGAU YABY RD, KUBIN VILLAGE, MOA ISLAND QLD 4875 Aurukun Island & Cape 39 KANG KANG RD, AURUKUN QLD 4892 Aurukun Supermarket Aurukun Kang Kang Café 502 KANG KAND RD, AURUKUN QLD 4892 Badu (Mulgrave) Island Badu Hotel 199 NONA ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Badu (Mulgrave) Island Island & Cape Badu MAIRU ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Supermarket (Bottom Shop) Badu (Mulgrave) Island J & J Supermarket 341 CHAPMAN ST, BADU ISLAND QLD (Top Shop) 4875 Badu (Mulgrave) Island T.S.I.R.C. - Badu NONA ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Bamaga Bamaga BP Service AIRPORT RD, BAMAGA QLD 4876 Station Bamaga Cape York Traders 201 LUI ST, BAMAGA QLD 4876 – Bamaga Store Bamaga CEQ – Bamaga 105 ADIDI AT, BAMAGA QLD 4876 Supermarket Boigu (Talbot) Island CEQ – Boigu TOBY ST, BOIGU QLD 4875 Supermarket Boigu (Talbot) Island T.S.I.R.C. - Boigu 66 CHAMBERS ST, BOIGU ISLAND QLD 4875 Darnley Island (Erub) Daido Tavern PILOT ST, DARNLEY ISLAND QLD 4875 Darnley Island (Erub) T.S.I.R.C. - Darnley COUNCIL OFFICE, DARNLEY ISLAND QLD 4875 Dauan Island (Mt CEQ - Dauan MAIN ST, DAUAN ISLAND QLD 4875 Cornwallis) Supermarket Dauan Island (Mt T.S.I.R.C. - Dauan COUNCIL OFFICE, MAIN ST, DAUAN Cornwallis) ISLAND QLD 4875 Doomadgee CEQ – Doomadgee 266 GUNNALUNJA DR, DOOMADGEE QLD Supermarket 4830 Doomadgee Doomadgee 1 GOODEEDAWA RD, DOOMADGEE -

Cairns to Undara Road Trip

Cairns to Estimated Days 3 Stop Overs 2 Undara Road Trip Via Mareeba and Chillagoe ANCIENT GEOLOGICAL WONDERS EXPERIENCE HIGHLIGHTS DAY ONE DAY THREE Port Douglas Mareeba Heritage Centre Bush Breakfast Camp 64 Dimbulah Archway Explorer Tour CAIRNS Mareeba Chillage-Mungana National Park Pinnarendi Station Café Chillagoe Royal Arch Cave Tour (1.30pm) Innot Hot Springs Atherton Karumba Ancient Aboriginal Rock Art Ravenshoe Bakery Innisfail Accomm: Chillagoe Cabins Cairns Ravenshoe Burketown Normanton Mount Garnet Mount Surprise Doomadgee Croydon Undara DAY TWO Georgetown Experience Sunrise at the Smelters Boodjamulla Einasleigh National Park Cobbold Gorge Donna Cave Tour (9am) Forsayth Swim at Chillagoe Weir Railway Hotel Almaden Australia’s AccessibleBurke and Wills Outback Undara Experience Roadhouse TOWNSVILLE Wildlife at Sunset Tour This three-day journey will take you to some of Australia’s most Accomm: Undara Experience incredible geological wonders from the outback town of Chillagoe to the incredible Undara Volcanic National Park. Charters Towers Julia Creek Hughenden Mt Isa Cloncurry For more information phone (07) 4097 1900 or visit www.undara.com.au Cairns to Undara Roadtrip DAY 1 Cairns to Chillagoe Via Mareeba & the Wheelbarrow Way Highlights: Local Coffee, Country Lunch, Cave Tour & Cultural History Set off early on your journey to Chillagoe-Mungana National Park, 215km or three hours drive west of Cairns, starting point of the Savannah Way, incorporating the Wheelbarrow Way. Once an ancient coral reef, this park on the edge of the outback is rich in natural and cultural heritage. It features spectacular limestone caves, small galleries of Aboriginal rock art, jagged limestone outcrops and an historically significant mining site. -

12 Days the Great Tropical Drive

ITINERARY The Great Tropical Drive Queensland – Cairns Cairns – Cooktown – Mareeba – Undara – Charters Towers – Townsville – Ingham – Tully/Mission Beach – Innisfail – Cairns Drive from Cairns to Townsville, through World Heritage-listed reef and rainforests to golden outback savannah. On this journey you won’t miss an inch of Queensland’s tropical splendour. AT A GLANCE Cruise the Great Barrier Reef and trek the ancient Daintree Rainforest. Connect with Aboriginal culture as you travel north to the remote frontier of Cape Tribulation. Explore historic gold mining towns and the lush orchards and plantations of the Tropical Tablelands. Day trip to Magnetic, Dunk and Hinchinbrook Islands and relax in resort towns like Port Douglas and Mission Beach. This journey has a short 4WD section, with an alternative road for conventional vehicles. > Cairns – Port Douglas (1 hour) > Port Douglas – Cooktown (3 hours) > Cooktown – Mareeba (4.5 hours) DAY ONE > Mareeba – Ravenshoe (1 hour) > Ravenshoe – Undara Volcanic Beach. Continue along the Cook Highway, CAIRNS TO PORT DOUGLAS National Park (2.5 hours) Meander along the golden chain of stopping at Rex Lookout for magical views over the Coral Sea beaches. Drive into the > Undara Volcanic National Park – beaches stretching north from Cairns. Surf Charters Towers (5.5 hours) at Machans Beach and swim at Holloways sophisticated tropical oasis Port Douglas, and palm-fringed Yorkey’s Knob. Picnic which sits between World Heritage-listed > Charters Towers – Townsville (1.5 hours) beneath sea almond trees in Trinity rainforest and reef. Walk along the white Beach or lunch in the tropical village. sands of Four Mile Beach and climb > Townsville – Ingham (1.5 hours) Flagstaff Hill for striking views over Port Hang out with the locals on secluded > Ingham – Cardwell (0.5 hours) Douglas.