The Days of Sail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virginia Horse Shows Association, Inc

2 VIRGINIA HORSE SHOWS ASSOCIATION, INC. OFFICERS Walter J. Lee………………………………President Oliver Brown… …………………….Vice President Wendy Mathews…...…….……………....Treasurer Nancy Peterson……..…………………….Secretary Angela Mauck………...…….....Executive Secretary MAILING ADDRESS 400 Rosedale Court, Suite 100 ~ Warrenton, Virginia 20186 (540) 349-0910 ~ Fax: (540) 349-0094 Website: www.vhsa.com E-mail: [email protected] 3 VHSA Official Sponsors Thank you to our Official Sponsors for their continued support of the Virginia Horse Shows Association www.mjhorsetransportation.com www.antares-sellier.com www.theclotheshorse.com www.platinumjumps.com www.equijet.com www.werideemo.com www.LMBoots.com www.vhib.org 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Officers ..................................................................................3 Official Sponsors ...................................................................4 Dedication Page .....................................................................7 Memorial Pages .............................................................. 8~18 President’s Page ..................................................................19 Board of Directors ...............................................................20 Committees ................................................................... 24~35 2021 Regular Program Horse Show Calendar ............. 40~43 2021 Associate Program Horse Show Calendar .......... 46~60 VHSA Special Awards .................................................. 63-65 VHSA Award Photos .................................................. -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

The Horse-Breeder's Guide and Hand Book

LIBRAKT UNIVERSITY^' PENNSYLVANIA FAIRMAN ROGERS COLLECTION ON HORSEMANSHIP (fop^ U Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/horsebreedersguiOObruc TSIE HORSE-BREEDER'S GUIDE HAND BOOK. EMBRACING ONE HUNDRED TABULATED PEDIGREES OF THE PRIN- CIPAL SIRES, WITH FULL PERFORMANCES OF EACH AND BEST OF THEIR GET, COVERING THE SEASON OF 1883, WITH A FEW OF THE DISTINGUISHED DEAD ONES. By S. D. BRUCE, A.i3.th.or of tlie Ainerican. Stud Boole. PUBLISHED AT Office op TURF, FIELD AND FARM, o9 & 41 Park Row. 1883. NEW BOLTON CSNT&R Co 2, Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1883, By S. D. Bruce, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. INDEX c^ Stallions Covering in 1SS3, ^.^ WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, ALPHABETICALLY ARRANGED, PAGES 1 TO 181, INCLUSIVE. PART SECOISTD. DEAD SIRES WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, PAGES 184 TO 205, INCLUSIVE, ALPHA- BETICALLY ARRANGED. Index to Sires of Stallions described and tabulated in tliis volume. PAGE. Abd-el-Kader Sire of Algerine 5 Adventurer Blythwood 23 Alarm Himvar 75 Artillery Kyrle Daly 97 Australian Baden Baden 11 Fellowcraft 47 Han-v O'Fallon 71 Spendthrift 147 Springbok 149 Wilful 177 Wildidle 179 Beadsman Saxon 143 Bel Demonio. Fechter 45 Billet Elias Lawrence ' 37 Volturno 171 Blair Athol. Glen Athol 53 Highlander 73 Stonehege 151 Bonnie Scotland Bramble 25 Luke Blackburn 109 Plenipo 129 Boston Lexington 199 Breadalbane. Ill-Used 85 Citadel Gleuelg... -

Teacher Background

Teacher Background Inquiry Description In many parts of the world today, notably in Asia, societies are rapidly transforming. A major part of this transformation is urbanization, the flocking of people from the countryside to cities. A sign of this transformation is the construction of tall buildings. Since the Lincoln Cathedral surpassed the Pyramids of Egypt in 1300 CE, all of the tallest buildings in the world were in Europe and North America. Then, in 1998, the Petronas Towers opened in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Today the five tallest buildings are in Asia (One World Trade Center in New York City is #6) These areas are being transformed because of their integration into the world economic system that itself was the result of the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century in Western societies and the subsequent growth and expansion of those western societies. Interestingly, tall buildings, known as skyscrapers, were a sign of urbanization and industrial growth in Europe and North America at that time. This unit explores the connections between industrialization, urbanization, and skyscrapers, and how it was that skyscrapers were able to be built when and how they were. Key areas of attention will be building materials and related technologies that allowed for taller structures. Teachers are encouraged to use the following notes as they prepare for this unit, and additional secondary resources are listed at the end of this document. Historical Background Agriculture and Monumental Architecture In the long arc of human history, there are two interesting phenomena that might seem separate, but in hindsight are closely related. On the one hand, people have continually intensified their food production, leading to the ability to sustain larger populations on the same amount of land with fewer direct food producers. -

Managing Change: Sustainable Approaches to the Conservation of the Built Environment

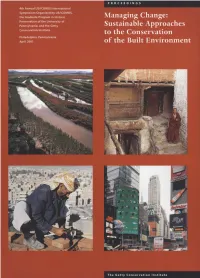

Managing Change: Sustainable Approaches to the Conservation of the Built Environment 4th Annual US/ICOMOS International Symposium Organized by US/ICOMOS, the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation of the University of Pennsylvania, and the Getty Conservation Institute Philadelphia, Pennsylvania April 2001 Edited by Jeanne Marie Teutonico and Frank Matero THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE Los ANGELES Cover: (top left) Rehabilitated raised fields at Illpa, Peru (photo by Clark L. Erickson); (top right) Interior of the monastery of Likir in Ladakh, India (photo by Ernesto Noriega); (bottom left) Master mason on the walls of the 'Addil Mosque, San 'a', Yemen (photo by Trevor Marchand); (bottom right) Times Square, New York City (copyright © Jeff Goldberg/Esto. All rights reserved.) Getty Conservation Institute Proceedings series © 2003 J. Paul Getty Trust Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu Timothy P. Whalen, Director, Getty Conservation Institute Jeanne Marie Teutonico, Associate Director, Field Projects and Science Sheila U. Berg, Project Manager and Manuscript Editor Pamela Heath, Production Coordinator Hespenheide Design, Designer Printed in the United States by Edwards Brothers, Inc. Cover and color insert printed in Canada by Transcontinental Printing The Getty Conservation Institute works internationally to advance conservation and to enhance and encourage the preservation and understanding of the visual arts in all of their dimensions—objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through scientific research, education and training, field projects, and the dissemination of the results of both its work and the work of others in the field. In all its endeavors, the Institute is committed to addressing unanswered questions and promoting the highest standards of conservation practice. -

2008 International List of Protected Names

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities _________________________________________________________________________________ _ 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Avril / April 2008 Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : ) des gagnants des 33 courses suivantes depuis leur ) the winners of the 33 following races since their création jusqu’en 1995 first running to 1995 inclus : included : Preis der Diana, Deutsches Derby, Preis von Europa (Allemagne/Deutschland) Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, Belmont Stakes, Jockey Club Gold Cup, Breeders’ Cup Turf, Breeders’ Cup Classic (Etats Unis d’Amérique/United States of America) Poule d’Essai des Poulains, Poule d’Essai des Pouliches, Prix du Jockey Club, Prix de Diane, Grand Prix de Paris, Prix Vermeille, Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe (France) 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Oaks, Derby, Ascot Gold Cup, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, St Leger, Grand National (Grande Bretagne/Great Britain) Irish 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Derby, Oaks, Saint Leger (Irlande/Ireland) Premio Regina Elena, Premio Parioli, Derby Italiano, Oaks (Italie/Italia) -

2009 International List of Protected Names

Liste Internationale des Noms Protégés LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities __________________________________________________________________________ _ 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] 2 03/02/2009 International List of Protected Names Internet : www.IFHAonline.org 3 03/02/2009 Liste Internationale des Noms Protégés La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : ) des gagnants des 33 courses suivantes depuis leur ) the winners of the 33 following races since their création jusqu’en 1995 first running to 1995 inclus : included : Preis der Diana, Deutsches Derby, Preis von Europa (Allemagne/Deutschland) Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, Belmont Stakes, Jockey Club Gold Cup, Breeders’ Cup Turf, Breeders’ Cup Classic (Etats Unis d’Amérique/United States of America) Poule d’Essai des Poulains, Poule d’Essai des Pouliches, Prix du Jockey Club, Prix de Diane, Grand Prix de Paris, Prix Vermeille, Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe (France) 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Oaks, Derby, Ascot Gold Cup, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, St Leger, Grand National (Grande Bretagne/Great Britain) Irish 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, -

Kirchner | Dissertation Master Document

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Cinemascapes: Cinematic Sublimity and Spatial Configurations ¾ or ¾ Learning from Los Angeles A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and TV by Carolin Kirchner 2018 ã Copyright by Carolin Kirchner 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Cinemascapes: Cinematic Sublimity and Spatial Configurations ¾ or ¾ Learning from Los Angeles by Carolin Kirchner Doctor of Philosophy in Film and TV University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Kathleen A McHugh Due to the shift in production practices and the availability of lighter camera equipment in the mid-1960s, filmmakers began to cinematically explore Los Angeles (LA) many environments. Utilizing the city’s diverse neighborhoods, unique architectural styles, and geographical topography, their films created imaginary spaces that sought to specifically represent LA, but also reflected post-war American urban restructuring processes in general. European filmmakers John Boorman, Jacques Demy, Agnès Varda, and Michelangelo Antonioni seemed to be especially perceptive regarding the specificity of the spaces they encountered in Los Angeles, and their films illustrate ambivalent feelings toward the built environment¾feelings that seem to run parallel to cultural and theoretical investigations taking place in the academy. Aided by the founding of the UCLA School of Architecture and Urban Planning, a new wave of scholars and theorists utilized ii Los Angeles in their writing as the most important case study for the postmodern megalopolis. Like Boorman, Demy, Varda, and Antonioni, neither of the leaders of this theoretical interest in Los Angeles¾ Kevin Lynch, Jane Jacobs, Reyner Banham, and Edward Soja ¾were native Californians. -

Geography, Cured Any Jail Get Again Twenty Jind Rue at J* a Dollars CJ.AKKSON

• V >;• .v-'a y* .■* '..4 -j5?v ti' ( $ ! PRECIPITATE, WONDER, Valuable Lands for Sale. Advertisement. Mr fool \ |*roi»T£Dby Light IsironTEu last fall was 12 T WIS FI to tell a HAL F SHARE in :te Dismal i f.e X last win- ■*• ■* SOI.D, to the highest bidder, on a eredi l 0f Bandy-Point. ;S Bu months in the Mutui- Swamp Company—also, SHARES in the Can,tl a ship f <d mrfo FIV F. 7 P 1 CTS O r u.r, full 15 I lands and half ■ TO month,. cello; will stand at my stable from Albemarle satfitd to Elizabeth rivet—- alto, > A to 7Hs*n,a» An 5 will stand at my ata- Tbtnt N*f) blunging theestiveof j,ip'h the ensuing season; and be let One of three 7 roe ft of LAND, lyitg tut dersvn ,di- vis:—O e in Cl 40< I blc in Chesicrneld county, mpbell county, </" to marts a; Six Guineas each Naiuemond river near Suffolk, the th»ee t> act a • ac e* on both tide* the main road, on th< > A river, 15 mil 's the inti- whole tying of pjximattox .... __marc reason, and a Oull;u mounting to about 1200 ace* 'ttv ii.uxLe* tract told ui nr*< above Pe to be let to of Bsautr creek tiki* tube ersburg, the groom ; but may he discharged with fire perron inf lined to par chose may Ik Utfot» cd tf tie car:, the ft:b > fthe tmrrth. to tr.ares at ten a April Campbell being day guineas provided they are paid by the first nay of October term* of *ale by drrc'ig a let'er tofhe rubso tier, Vid <<n Ctt■ two of which will be remitted if with- One in jlutetnur*County;>f acres.lying mare, paid next. -

2020 CATALOG It Has Now Been 20 Years Since the Launch of Our Very First Game, Gobblet

2020 CATALOG It has now been 20 years since the launch of our very first game, Gobblet. As we always say “time flies when you’re having fun’’ and it is especially true when Hello! you are a game company that partners with wonderful toy stores like yours! As we enter a new decade in an ever changing industry and retail world; we are very proud to introduce to you our newest catalog. Our team has worked very hard developing the best games possible while staying true to our commitment to bringing quality games that ignite family fun and develop children’s skills. Please join us in celebrating Blue Orange 20th Anniversary and making 2020 our best year yet! – Martin Marechal, CEO, Blue Orange Games USA Award-Winning Games We have received over 250 awards, including: AblePlay Award Seal Mensa Select Academic’s Choice Brain Toy NAPPA Gold Winner ASTRA Best Toys for Kids Oppenheim Platinum Seal Creative Child Magazine’s Parents’ Choice Gold Award Game of the Year Spiel des Jahres Dice Tower Seal of Excellence Tillywig Top Fun Award Play Advances Language Award Global Educator Institute Seal Major Fun! Award Community Initiatives At Blue Orange Games, we understand the importance of giving back to the community. As a company, we actively work to create partnerships that will directly benefit children while also promoting the value of play. Our ongoing efforts include donating to schools, libraries, therapy centers and disaster relief organizations. We also sponsor local game nights, meet-ups, and special events across the country. In our local community, we reach 1,000 kids each summer through “play days” at dozens of summer camps, and have hopes to expand this program. -

Corps of Discovery Hats 20 What Did the Explorers Really Wear on Their Heads? by Bob Moore

Chinook Point Decision Columbia Gorge John Ordway White House Ceremony The Official Publication of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc. May 2001 Volume 27, No. 2 C ORPS OF DISCOVERY HATS What did Lewis & Clark and their men really wear on their heads? ROW 4/C AD The Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc. P.O. Box 3434, Great Falls, Montana 59403 Ph: 406-454-1234 or 1-888-701-3434 Fax: 406-771-9237 www.lewisandclark.org Mission Statement The mission of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc. is to stimulate public appreciation of the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s contributions to America’s heritage and to support education, research, development, and preservation of the Lewis and Clark experience. Officers Active Past Presidents Directors at large President David Borlaug Beverly Hinds Cindy Orlando Washburn, North Dakota Sioux City, Iowa 1849 “C” St., N.W. Washington, DC 20240 Robert K. Doerk, Jr. James Holmberg Fort Benton, Montana Louisville, Kentucky President-Elect Barbara Kubik James R. Fazio Ron Laycock 10808 N.E. 27th Court Moscow, Idaho Benson, Minnesota Vancouver, WA 98686 Robert E. Gatten, Jr. Larry Epstein Vice-President Greensboro, North Carolina Cut Bank, Montana Jane Henley 1564 Heathrow Drive H. John Montague Dark Rain Thom Keswick, VA 22947 Portland, Oregon Bloomington, Indiana Secretary Clyde G. “Sid” Huggins Joe Mussulman Ludd Trozpek Covington, Louisiana Lolo, Montana 4141 Via Padova Claremont, CA 91711 Donald F. Nell Robert Shattuck Bozeman, Montana Grass Valley, California Treasurer Jerry Garrett James M. Peterson Jane SchmoyerWeber 10174 Sakura Drive Vermillion, South Dakota Great Falls, Montana St. -

American Art

American Art The Art Institute of Chicago American Art New Edition The Art Institute of Chicago, 2008 Produced by the Department of Museum Education, Division of Teacher Programs Robert W. Eskridge, Woman’s Board Endowed Executive Director of Museum Education Writers Department of American Art Judith A. Barter, Sarah E. Kelly, Ellen E. Roberts, Brandon K. Ruud Department of Museum Education Elijah Burgher, Karin Jacobson, Glennda Jensen, Shannon Liedel, Grace Murray, David Stark Contributing Writers Lara Taylor, Tanya Brown-Merriman, Maria Marable-Bunch, Nenette Luarca, Maura Rogan Addendum Reviewer James Rondeau, Department of Contemporary Art Editors David Stark, Lara Taylor Illustrations Elijah Burgher Graphic Designer Z...ART & Graphics Publication of American Art was made possible by the Terra Foundation for American Art and the Woman’s Board of the Art Institute of Chicago. Table of Contents How To Use This Manual ......................................................................... ii Introduction: America’s History and Its Art From Its Beginnings to the Cold War ............... 1 Eighteenth Century 1. Copley, Mrs. Daniel Hubbard (Mary Greene) ............................................................ 17 2. Townsend, Bureau Table ............................................................................... 19 Nineteenth Century 3. Rush, General Andrew Jackson ......................................................................... 22 4. Cole, Distant View of Niagara Falls ....................................................................