22 & 23 June 2015 Cutler's Hall Sheffield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sheffield Town Walk

6 8 7 1 1 P D this document please recycle it recycle please document this on 55% recycled paper recycled 55% on When you have finished with finished have you When This document is printed is document This 55% k u . v o g . d l e i f f e h s . w w w s e c i v r e S t n e m p o l e v e D g n i k l a w / k u . v o g . d l e i f f e h s . w w w l i c n u o C y t i C d l e i f f e h S m u r o F g n i k l a W d l e i f f e h S ) 5 1 ( e r a u q S e s i d a r a P 4 0 4 4 3 7 2 4 1 1 0 t c a t n o c e s a e l p y b d e c u d o r P . n a g e b , s t a m r o f e v i t a n r e t l a n i d e i l p p u s ) 6 1 ( e u g o g a n y S k l a w e h t e r e h w e d a r a P e b n a c t n e m u c o d s i h T t s a E o t n o k c a b t f e l t s a p e h t f o s e o h c E K L A W s s o r C • n r u t – t h g i r n r u t – e n a L o p m a C . -

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian . -

Country Airplay; Brooks and Shelton ‘Dive’ In

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS JUNE 24, 2019 | PAGE 1 OF 19 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Thomas Rhett’s Behind-The-Scenes Country Songwriters “Look” Cooks >page 4 Embracing Front-Of-Stage Artist Opportunities Midland’s “Lonely” Shoutout When Brett James sings “I Hold On” on the new Music City Puxico in 2017 and is working on an Elektra album as a member >page 9 Hit-Makers EP Songs & Symphony, there’s a ring of what-ifs of The Highwomen, featuring bandmates Maren Morris, about it. Brandi Carlile and Amanda Shires. Nominated for the Country Music Association’s song of Indeed, among the list of writers who have issued recent the year in 2014, “I Hold On” gets a new treatment in the projects are Liz Rose (“Cry Pretty”), Heather Morgan (“Love Tanya Tucker’s recording with lush orchestration atop its throbbing guitar- Someone”), and Jeff Hyde (“Some of It,” “We Were”), who Street Cred based arrangement. put out Norman >page 10 James sings it with Rockwell World an appropriate in 2018. gospel-/soul-tinged Others who tone. Had a few have enhanced Marty Party breaks happened their careers with In The Hall differently, one a lbu ms i nclude >page 10 could envision an f o r m e r L y r i c alternate world in Street artist Sarah JAMES HUMMON which James, rather HEMBY Buxton ( “ S u n Makin’ Tracks: than co-writer Daze”), who has Riley Green’s Dierks Bentley, was the singer who made “I Hold On” a hit. done some recording with fellow songwriters and musicians Sophomore Single James actually has recorded an entire album that’s expected under the band name Skyline Motel; Lori McKenna (“Humble >page 14 later this year, making him part of a wave of writers who are and Kind”), who counts a series of albums along with her stepping into the spotlight with their own multisong projects. -

Sheffield Development Framework Core Strategy Adopted March 2009

6088 Core Strategy Cover:A4 Cover & Back Spread 6/3/09 16:04 Page 1 Sheffield Development Framework Core Strategy Adopted March 2009 Sheffield Core Strategy Sheffield Development Framework Core Strategy Adopted by the City Council on 4th March 2009 Development Services Sheffield City Council Howden House 1 Union Street Sheffield S1 2SH Sheffield City Council Sheffield Core Strategy Core Strategy Availability of this document This document is available on the Council’s website at www.sheffield.gov.uk/sdf If you would like a copy of this document in large print, audio format ,Braille, on computer disk, or in a language other than English,please contact us for this to be arranged: l telephone (0114) 205 3075, or l e-mail [email protected], or l write to: SDF Team Development Services Sheffield City Council Howden House 1 Union Street Sheffield S1 2SH Sheffield Core Strategy INTRODUCTION Chapter 1 Introduction to the Core Strategy 1 What is the Sheffield Development Framework about? 1 What is the Core Strategy? 1 PART 1: CONTEXT, VISION, OBJECTIVES AND SPATIAL STRATEGY Chapter 2 Context and Challenges 5 Sheffield: the story so far 5 Challenges for the Future 6 Other Strategies 9 Chapter 3 Vision and Objectives 13 The Spatial Vision 13 SDF Objectives 14 Chapter 4 Spatial Strategy 23 Introduction 23 Spatial Strategy 23 Overall Settlement Pattern 24 The City Centre 24 The Lower and Upper Don Valley 25 Other Employment Areas in the Main Urban Area 26 Housing Areas 26 Outer Areas 27 Green Corridors and Countryside 27 Transport Routes 28 PART -

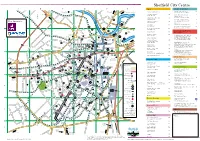

Accommodation in Sheffield

Sheffield City Centre ABCDEFArts Sport & Leisure L L T A6135 to Northern I E The Edge Climbing Centre C6 H E Kelham Island T R To Don Valley Stadium, Arena, Meadowhall Galleries and Museums General Hospital L S and M1 motorway (junction 34) John Street, 0114 275 8899 G R Museum S A E E T L E FIELD I I SHALESMOOR N ITAL V L SP P S A A N S Graves Art Gallery D4 S E Ponds Forge International E3 H L M A S N A T R S 0114 278 2600 A E E T U L T Sports Centre E R S A M S T N E E Sheaf Street, 0114 223 3400 O ST E STREET T R O R L S Kelham Island Museum C1 R Y E 1 GRN M Y 0114 272 2106 A61 T A M S H Sheffield Ice Sports Centre E6 M E P To Barnsley, Huddersfield, S T S E O G T P E R JOHNSON T A E Leeds and Manchester O R N Queens Road, 0114 272 3037 D E R R E R I R BOWLING I F Millennium Galleries D4 Map Sponsors via Woodhead F N T E E O T I E F E S T W S L G T R E E D 0114 278 2600 L S S B E SPA 1877 A4 T G I B N Y T R E R A CUT O L R O K E T I L E Victoria Street, 0114 221 1877 H A E I R 3 D S R R E C ’ G Site Gallery E5 T S T A T S T T G I E R A D E 0114 281 2077 E R W R E P R A Sheffield United Football Club C6 E O H T S O P i P T R Bramall Lane, 0870 787 1960 v E R R S N D Turner Museum of Glass B3 T H e 48 S O E A R ST P r O E I 0114 222 5500 C O E T E T D R T LOVE A P T L Transport & Travel o S A V Winter Garden D4 n A I I N Enquiries B R L R P O O N U K T Fire/Police S P F Yorkshire Artspace D5 B R I D T C Law Courts G E RE I Personal enquiries can be made at: Museum S T E 12 V i n S C O R E E T T s 0114 276 1769 T L A N a Sheffield Interchange for bus, tram T D S C A S T L B E T R West Bar E G A T E 2 l E E E W S a or coach (National Express). -

Wells Fargo Center for the Arts Presents Rock & Roll Hall of Fame

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Media Contact: Anne Abrams Charles Zukow Associates 415.296.0677 or [email protected] Print quality images available: http://wellsfargocenterarts.org/media/ Wells Fargo Center for the Arts presents Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Inductees HEART In Concert Thursday, September 25 Tickets go on sale June 13 at noon SANTA ROSA, CA (June 2, 2014) – Wells Fargo Center for the Arts presents Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductees HEART in concert Thursday September 25 at 8:00 pm in the Ruth Finley Person Theater (50 Mark West Springs Rd. Santa Rosa, CA). More than 3 decades after their first big hit, sisters Ann and Nancy Wilson were back on the Billboard Top 10 in 2010 with HEART’S “Red Velvet Car” album, and a Top 5 DVD (“Night at Sky Church”). Tickets for the HEART concert, which go on sale Friday June 13 at noon are $115, $75 and $65 and may be purchased online at wellsfargocenterarts.org, by calling 707.546.3600 or in person at the box office at 50 Mark West Springs Road in Santa Rosa. Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductees Ann and Nancy Wilson first showed the world that women can rock when their band, HEART, stormed the charts in the ‘70’s with multiple hits including “Crazy on You,” “Magic Man,” “Barracuda,” “Straight On.” Not only did the Wilson sisters lead the band, they wrote the songs and played the instruments too, making them the first women in rock to do so. HEART continued topping the charts through the ‘80’s and ‘90’s with huge hits like “These Dreams,” “Alone,” “What About Love,” “If Looks Could Kill,” “Never,” and a string of other hits that showcased the sisters’ enormous talents as musicians and singers. -

Sheffield Local Plan (Formerly Sheffield Development Framework)

Sheffield Local Plan (formerly Sheffield Development Framework) Consultation Schedule – City Policies and Sites Consultation Draft 2010 Full Schedule of individual comments and Council responses on the City Policies and Sites Consultation Draft, Proposals Map and Sustainability Appraisal – June 2010 Representations on City Policies and Sites Consultation Draft................................................................2 Representations on City Policies and Sites Proposals Map………………………………………………112 Representations on City Policies and Sites Consultation Draft Sustainability Appraisal………………136 Representations on City Policies and Sites Consultation Draft Document Section Comment Name of individual/ Nature of Summary of Comment Council response Recommendation ID organisation comment Introduction - General dcps13 Mr Derek Hastings, Object Paragraph 1.7 should reflect that Government policy documents Local development plan policy must be consistent with national No change is proposed. comment Rivelin Valley are non-statutory and that, under the plan-led system, planning policy and the new National Planning Policy Framework will Conservation Group policies should be included in the Development Plan to carry carry considerable weight. But there is no need to duplicate it. maximum weight. Although this can leave the impression of omissions from local policy, duplicating national policy will not add any further weight and any variations in wording could create uncertainty about which applies . Introduction - General dcps14 Mr Derek Hastings, Object The proposed "cull" of planning policies is unacceptable. The The issue is partly dealt with in the response to dcps13. The No change is proposed. comment Rivelin Valley length of the document is irrelevant. Policies included in non- issue of length is relevant, having been raised by the Core Conservation Group statutory national or local policy carry less weight than the Strategy Inspector. -

Central Community Assembly Area Areas and Sites

Transformation and Sustainability SHEFFIELD LOCAL PLAN (formerly Sheffield Development Framework) CITY POLICIES AND SITES DOCUMENT CENTRAL COMMUNITY ASSEMBLY AREA AREAS AND SITES BACKGROUND REPORT Development Services Sheffield City Council Howden House 1 Union Street SHEFFIELD S1 2SH June 2013 CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. Introduction 1 Part 1: City Centre 2. Policy Areas in the City Centre 5 3. Allocated Sites in the City Centre 65 Part 2: Sheaf Valley and Neighbouring Areas 4. Policy Areas in Sheaf Valley and Neighbouring Areas 133 5. Allocated Sites in Sheaf Valley and Neighbouring Areas 175 Part 3: South and West Urban Area 6. Policy Areas in the South and West Urban Area 177 7. Allocated Sites in the South and West Urban Area 227 Part 4: Upper Don Valley 8. Policy Areas 239 9. Allocated Sites in Upper Don Valley 273 List of Tables Page 1 Policy Background Reports 3 2 Potential Capacity of Retail Warehouse Allocations 108 List of Figures Page 1 Consolidated Central and Primary Shopping Areas 8 2 Illustrative Block Plan for The Moor 9 3 Current Street Level Uses in the Cultural Hub 15 4 Priority Office Areas 21 5 City Centre Business Areas 28 6 City Centre Neighbourhoods 46 7 City Centre Open Space 57 8 Bramall Lane/ John Street 139 1. INTRODUCTION The Context 1.1 This report provides evidence to support the published policies for the City Policies and Sites document of the Sheffield Local Plan. 1.2 The Sheffield Local Plan is the new name, as used by the Government, for what was known as the Sheffield Development Framework. -

Kean Stage Presents Heart by Heart on Sept. 23 | NJ.Com

8/27/2017 Kean Stage presents Heart By Heart on Sept. 23 | NJ.com Menu Set Weather Subscribe Search SUBURBAN NEWS Kean Stage presents Heart By Heart on Sept. 23 Updated on August 26, 2017 at 5:28 PM Comment Posted on August 26, 2017 at 5:27 PM 0 shares By Community Bulletin Relive the heyday of the chart-topping 1970s rock band Heart at Kean Stage. Steve Fossen and Mike Derosier, the original bassist and drummer who were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame with Heart, have reformed as a new band, Heart by Heart, and they have recreated iconic hits such as Magic Man, Barracuda, Straight On, Even It Up, Crazy On You, Dog And Butterfly and Heartless. Heart By Heart will perform at Kean Stage's Wilkins Theatre on Saturday, Sept. 23, at 7:30 p.m. "Michael and I were heavily involved in the writing, recording and mixing process back then," said Fossen. "There's no other rhythm section out there that can play the music as faithfully to the recordings as we do. Seeing Mike play is a really big treat for anyone who appreciates good drummers." Heart by Heart also features vocalist Somar Macek as lead singer, along with guitarist/keyboardist/vocalist Lizzy Daymont, and legendary Seattle guitarist Randy Hansen. They consider it their responsibility to bring the songs to the stage in their original form without updating or reworking them. "We're very lucky to have Somar and Lizzy," Fossen said. "They're very talented and they love the music. -

Colocation Aware Content Sharing in Urban Transport

Colocation Aware Content Sharing in Urban Transport Liam James John McNamara A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University College London. Department of Computer Science January 2010 I, Liam James John McNamara confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. i Abstract People living in urban areas spend a considerable amount of time on public transport. During these periods, opportunities for inter-personal networking present themselves, as many of us now carry electronic devices equipped with Bluetooth or other wireless capabilities. Using these devices, individuals can share content (e.g., music, news or video clips) with fellow travellers that happen to be on the same train or bus. Transferring media takes time; in order to maximise the chances of successfully completing interesting downloads, users should identify neighbours that possess desirable content and who will travel with them for long-enough periods. In this thesis, a peer-to-peer content distribution system for wireless devices is proposed, grounded on three main contributions: (1) a technique to predict colocation durations (2) a mechanism to exclude poorly performing peers and (3) a library advertisement protocol. The prediction scheme works on the observation that people have a high degree of regularity in their movements. Ensuring that content is accurately described and delivered is a challenge in open networks, requiring the use of a trust framework, to avoid devices that do not behave appro- priately. -

Sheffield: a Civilised Place

Sheffield: A Civilised Place Loop 1 (2 miles / 1-1½ hours) Go through the Interchange to Pond Hill Continue up Commercial Street. and turn sharp right. Sheffield’s first tram network began in Opened in 2002, The Winter Garden is 18 1 Amongst the modern buildings sits 1872, expanding over the following 40 heated, as are many city centre buildings, by 12 the Old Queen’s Head - a 15th years, finally to close in 1960. Work began the Sheffield District Heating scheme, which creates century timber framed hall. It is the oldest on the Supertram in 1991 with the last part energy from waste. The under-floor heating system domestic building in the city, and was carefully of the three-line network opening in 1995. provides a heated environment for around 2500 restored in 1992-3. semi-tropical plants. The building’s structure has an inverted catenary form to the arches. 13The River Sheaf was culverted in Follow the tram tracks up High Street towards the Cathedral. the 1860s as the city expanded into Leave the Winter Garden and cross Tudor Square. the river valley, with improvements to the markets and development of the railway. The Lyceum Theatre, originally built 2 The Foster’s Buildings at the in 1893, was refurbished in 1991. The At the end of Pond Hill, turn left on 19junction of High Street and new extension to the right of the building Sheaf Street. Fargate were, in 1894, the first in provides better bar and circulation areas than Sheffield to operate a lift. The top of the retained rotunda to the left. -

Ann and Nancy Wilson Set to Make “These Dreams” Come True for Fans and Collectors with Collection of HEART at Julien’S Auctions

For Immediate Release: Ann and Nancy Wilson Set to Make “These Dreams” Come True for Fans and Collectors with Collection of HEART at Julien’s Auctions Costumes and Personal Items from Heart’s Celebrated Four Decade Career to Be Auctioned in Exclusive Rock n’ Roll Experience November 7-8, 2014 Beverly Hills, California — (October 6, 2014) — Julien’s Auctions, the world’s premier entertainment and music memorabilia auction house, has announced The Collection of Ann and Nancy Wilson of the mega-rock group Heart auction event featuring custom made stage costumes and personal items to take place on November 7 and 8, 2014 at Julien’s Auctions Beverly Hills. The award-winning collection includes a vast amount of custom made costumes and stage worn clothing, personal items and professional awards from the careers of sisters Ann and Nancy Wilson. (photo left: Ann Wilson stage-worn dress) Heart has sold over 35 million records worldwide, has had twenty Top 40 singles, seven “Top 10” albums and four GRAMMY Award nominations. The band has had “Top 10” albums on the Billboard charts over a series of decades beginning in the 1970’s and through 2010. Ann and Nancy Wilson’s career spans over four decades making them the premiere female fronted rock band holding the record for the longest time span anywhere in the universe. In 2013, Heart was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. (photo right: Nancy Wilson tour used guitar) Ann and Nancy Wilson set the stage for all female rockers when they first formed the band in 1974.