Coronado National Forest Management Indicator Species Population Status and Trends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

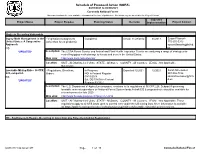

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Coronado National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Coronado National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Gypsy Moth Management in the - Vegetation management Completed Actual: 11/28/2012 01/2013 Susan Ellsworth United States: A Cooperative (other than forest products) 775-355-5313 Approach [email protected]. EIS us *UPDATED* Description: The USDA Forest Service and Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service are analyzing a range of strategies for controlling gypsy moth damage to forests and trees in the United States. Web Link: http://www.na.fs.fed.us/wv/eis/ Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Nationwide. Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Sarah Shoemaker 228, subpart A. Orders NOI in Federal Register 907-586-7886 EIS 09/13/2018 [email protected] d.us *UPDATED* Est. DEIS NOA in Federal Register 03/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. -

Bear Wallow-Mt. Lemmon Area, Santa Catalina

Structural geology of the Mt. Bigelow-Bear Wallow- Mt. Lemmon area, Santa Catalina Mountains, Arizona Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic); maps Authors Waag, Charles Joseph, 1931- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 11/10/2021 07:04:44 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565165 STRUCTURAL GEOLOGY OF THE MT. BIGELOW- BEAR WALLOW-MT. LEMMON AREA, SANTA CATALINA MOUNTAINS, ARIZONA by Charles Joseph Waag A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 8 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Charles J« Waag_________________________________ entitled STRUCTURAL GEOLOGY OF THE MT. BIGELOW-BEAR WALLOW- MT. LEMMON AREA, SANTA CATALINA MOUNTAINS, ARIZONA be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy______________________________ % /96r After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:* This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination. The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dissertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examination. -

Coronado National Forest Draft Land and Resource Management Plan I Contents

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Coronado National Forest Southwestern Region Draft Land and Resource MB-R3-05-7 October 2013 Management Plan Cochise, Graham, Pima, Pinal, and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona, and Hidalgo County, New Mexico The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Front cover photos (clockwise from upper left): Meadow Valley in the Huachuca Ecosystem Management Area; saguaros in the Galiuro Mountains; deer herd; aspen on Mt. Lemmon; Riggs Lake; Dragoon Mountains; Santa Rita Mountains “sky island”; San Rafael grasslands; historic building in Cave Creek Canyon; golden columbine flowers; and camping at Rose Canyon Campground. Printed on recycled paper • October 2013 Draft Land and Resource Management Plan Coronado National Forest Cochise, Graham, Pima, Pinal, and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona Hidalgo County, New Mexico Responsible Official: Regional Forester Southwestern Region 333 Broadway Boulevard, SE Albuquerque, NM 87102 (505) 842-3292 For Information Contact: Forest Planner Coronado National Forest 300 West Congress, FB 42 Tucson, AZ 85701 (520) 388-8300 TTY 711 [email protected] Contents Chapter 1. -

The Birds of Hacienda Palo Verde, Guanacaste, Costa Rica

The Birds of Hacienda Palo Verde, Guanacaste, Costa Rica PAUL SLUD SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY • NUMBER 292 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoo/ogy Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world cf science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. Press requirements for manuscript and art preparation are outlined on the inside back cover. -

Table of Contents

TABLEGUIDELINES OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 12: CONTACT INFORMATION AND MAPS 12.1 ADOT CONTACT INFORMATION……………………………………………….......122 12.2 BLM CONTACT INFORMATION…………………………………………………......123 12.3 USFS CONTACT INFORMATION………………………………………………….....124 12.4 FHWA CONTACT INFORMATION…………………………………………………....130 12.5 GIS INFORMATION..............................................................................................131 12.6 MAPS...................................................................................................................132 121 12.1 ADOT CONTACT INFORMATION ADOT web link azdot.gov/ ADOT maps azdot.gov/maps General Information 602-712-7355 OFFICE ADOT DIRECTOR 602.712.7227 Deputy Director of Transportation 602.712.7391 Deputy Director of Policy 602.712.7550 Deputy Director of Business Operations 602.712.7228 Multimodal Planning Division (MPD) Director 602.712.7431 MPD Planning and Programming Director 602.712.8140 MPD Planning and Environmental Linkages Manager 602.712.4574 Infrastructure Delivery and Operations Division (IDO) 602.712.7391 State Engineer, Sr. Deputy State Engineer and Deputy State Engineer Offices 602.712.7391 DISTRICT ENGINEERS Northcentral azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/northcentral 928.774.1491 Northeast azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/northeast 928.524.5400 Central Construction District azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/central 602.712.8965 Central Maintenance District azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/central 602.712.6664 Northwest azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/northwest 928.777.5861 -

Lincoln National Forest

Chapter 1: Introduction In Ecological and Biological Diversity of National Forests in Region 3 Bruce Vander Lee, Ruth Smith, and Joanna Bate The Nature Conservancy EXECUTIVE SUMMARY We summarized existing regional-scale biological and ecological assessment information from Arizona and New Mexico for use in the development of Forest Plans for the eleven National Forests in USDA Forest Service Region 3 (Region 3). Under the current Planning Rule, Forest Plans are to be strategic documents focusing on ecological, economic, and social sustainability. In addition, Region 3 has identified restoration of the functionality of fire-adapted systems as a central priority to address forest health issues. Assessments were selected for inclusion in this report based on (1) relevance to Forest Planning needs with emphasis on the need to address ecosystem diversity and ecological sustainability, (2) suitability to address restoration of Region 3’s major vegetation systems, and (3) suitability to address ecological conditions at regional scales. We identified five assessments that addressed the distribution and current condition of ecological and biological diversity within Region 3. We summarized each of these assessments to highlight important ecological resources that exist on National Forests in Arizona and New Mexico: • Extent and distribution of potential natural vegetation types in Arizona and New Mexico • Distribution and condition of low-elevation grasslands in Arizona • Distribution of stream reaches with native fish occurrences in Arizona • Species richness and conservation status attributes for all species on National Forests in Arizona and New Mexico • Identification of priority areas for biodiversity conservation from Ecoregional Assessments from Arizona and New Mexico Analyses of available assessments were completed across all management jurisdictions for Arizona and New Mexico, providing a regional context to illustrate the biological and ecological importance of National Forests in Region 3. -

A GUIDE to the GEOLOGY of the Santa Catalina Mountains, Arizona: the Geology and Life Zones of a Madrean Sky Island

A GUIDE TO THE GEOLOGY OF THE SANTA CATALINA MOUNTAINS, ARIZONA: THE GEOLOGY AND LIFE ZONES OF A MADREAN SKY ISLAND ARIZONA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 22 JOHN V. BEZY Inside front cover. Sabino Canyon, 30 December 2010. (Megan McCormick, flickr.com (CC BY 2.0). A Guide to the Geology of the Santa Catalina Mountains, Arizona: The Geology and Life Zones of a Madrean Sky Island John V. Bezy Arizona Geological Survey Down-to-Earth 22 Copyright©2016, Arizona Geological Survey All rights reserved Book design: M. Conway & S. Mar Photos: Dr. Larry Fellows, Dr. Anthony Lux and Dr. John Bezy unless otherwise noted Printed in the United States of America Permission is granted for individuals to make single copies for their personal use in research, study or teaching, and to use short quotes, figures, or tables, from this publication for publication in scientific books and journals, provided that the source of the information is appropriately cited. This consent does not extend to other kinds of copying for general distribution, for advertising or promotional purposes, for creating new or collective works, or for resale. The reproduction of multiple copies and the use of articles or extracts for comer- cial purposes require specific permission from the Arizona Geological Survey. Published by the Arizona Geological Survey 416 W. Congress, #100, Tucson, AZ 85701 www.azgs.az.gov Cover photo: Pinnacles at Catalina State Park, Courtesy of Dr. Anthony Lux ISBN 978-0-9854798-2-4 Citation: Bezy, J.V., 2016, A Guide to the Geology of the Santa Catalina Mountains, Arizona: The Geology and Life Zones of a Madrean Sky Island. -

Southwestern Region Map Order Form

Southwestern Region Map Order Form National Forest and Grassland Visitor Maps Wilderness Maps Arizona Arizona Location Qty Price Total Location Qty Price Total Apache-Sitgreaves $14 Blue Range (Apache) $14 Coconino $14 Granite Mountain (Prescott) $14 Coronado (Santa Catalina & Safford Districts) $14 Juniper Mesa/Apache Creek (Prescott) $14 Coronado (Sierra Vista & Nogales Districts) $14 Mazatzal (Tonto) $14 Coronado (Douglas District) $14 Mt. Baldy (Apache) $14 Coronado N. Chiricahua Mountains. & Chiricahua National $14 Mt. Wrightson and Pajarita (Coronado) $14 Monument Pusch Ridge (Coronado) $14 Kaibab (North) $14 Superstition (Tonto) $14 Kaibab (Tusayan & Williams Districts) $14 Sycamore Canyon Wilderness (Coconino, Kaibab, and Prescott) $14 Prescott $14 Tonto $14 New Mexico Location Qty Price Total New Mexico Apache Kid/Withington (Cibola) $14 Location Qty Price Total Aldo Leopold (Gila) $14 Carson $14 Capitan Mountains (Lincoln) $14 Cibola (Magdalena District) $14 Cruces Basin (Carson) $14 Cibola (Mt. Taylor District) $14 Gila $14 Cibola (Mountainair District) $14 Latir Peak/Wheeler Peak (Carson) $14 Cibola (Sandia District) $14 Manzano Mountains (Cibola) $14 Cibola (Kiowa/Rita Blanca National Grasslands – New Mexico, $14 Pecos (Santa Fe) $14 Oklahoma, Texas) San Pedro Parks (Santa Fe) $14 Cibola (Black Kettle National Grasslands - Oklahoma) $14 White Mountain (Lincoln) $14 Gila $14 Lincoln (Smokey Bear & Sacramento Districts) $14 Lincoln (Guadalupe District) $14 Totals Santa Fe $14 Quantity Total Other Map Products Location Qty Price Total Name: _________________________________________________________________ AZ Big Game Hunting Unit Topographic Map Index $2 Address: ________________________________________________________________ NM Big Game Hunting Unit Topographic Map Index $2 City, State, Zip ___________________________________________________________ Gila Day Hikes near Gila Visitor Center $2 Phone __________________________________________________________________ Mt. -

Bird Checklist

Gray-cheeked Thrush Catharus minimus Blackburnian Warbler Dendroica fusca Field Sparrow Spizella pusilla Swainson’s Thrush Catharus ustulatus American Redstart Setophaga ruticilla Swamp Sparrow Melospiza georgiana National Park Service Hermit Thrush Catharus guttatus Pine Warbler Dendroica pinus American Tree Sparrow Spizella arborea U.S. Department of the Interior Veery Catharus fuscescens Prairie Warbler Dendroica discolor Grasshopper Ammodramus savannarum Wood Thrush Hylocichla mustelina Palm Warbler Dendroica palmarum Sparrow New River Gorge National River Blue-winged Warbler Vermivora pinus Fox Sparrow Passeralla iliaca Mockingbird and Thrasher Family Yellow Warbler Dendroica petechia Song Sparrow Melospiza melodia (Mimidae) Swainson’s Warbler Limnothlypis swainsonii Vesper Sparrow Pooecetes gramineus Brown Thrasher Toxostoma rufum Worm-eating Helmitheros vermivorus Savannah Sparrow Passerculus sandwichensis Bird Checklist Gray Catbird Dumetella carolinensis Warbler Dark-eyed (“Slate-colored”) Junco hyemalis Northern Mockingbird Mimus polyglottos Tennessee Warbler Vermivora peregrina Junco Wilson’s Warbler Wilsonia pusilla Crow and Jay Family (Corvidae) Hooded Warbler Wilsonia citrina Blackbird and Oriole Family (Icteridae) Blue Jay Cyanocitta cristata Golden-winged Vermivora chrysoptera Rusty Blackbird Euphagus carolinus American Crow Corvus brachyrhynchos Warbler Common Grackle Quiscalus quiscula Common Raven Corvus corax Nashville Warbler Vermivora ruficapilla Red-winged Blackbird Agelaius phoeniceus Kentucky Warbler Oporornis -

Costa Rica: the Introtour | July 2017

Tropical Birding Trip Report Costa Rica: The Introtour | July 2017 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour Costa Rica: The Introtour July 15 – 25, 2017 Tour Leader: Scott Olmstead INTRODUCTION This year’s July departure of the Costa Rica Introtour had great luck with many of the most spectacular, emblematic birds of Central America like Resplendent Quetzal (photo right), Three-wattled Bellbird, Great Green and Scarlet Macaws, and Keel-billed Toucan, as well as some excellent rarities like Black Hawk- Eagle, Ochraceous Pewee and Azure-hooded Jay. We enjoyed great weather for birding, with almost no morning rain throughout the trip, and just a few delightful afternoon and evening showers. Comfortable accommodations, iconic landscapes, abundant, delicious meals, and our charismatic driver Luís enhanced our time in the field. Our group, made up of a mix of first- timers to the tropics and more seasoned tropical birders, got along wonderfully, with some spying their first-ever toucans, motmots, puffbirds, etc. on this trip, and others ticking off regional endemics and hard-to-get species. We were fortunate to have several high-quality mammal sightings, including three monkey species, Derby’s Wooly Opossum, Northern Tamandua, and Tayra. Then there were many www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Costa Rica: The Introtour | July 2017 superb reptiles and amphibians, among them Emerald Basilisk, Helmeted Iguana, Green-and- black and Strawberry Poison Frogs, and Red-eyed Leaf Frog. And on a daily basis we saw many other fantastic and odd tropical treasures like glorious Blue Morpho butterflies, enormous tree ferns, and giant stick insects! TOP FIVE BIRDS OF THE TOUR (as voted by the group) 1. -

USDA Forest Service Youth Conservation Corps Projects 2021

1 USDA Forest Service Youth Conservation Corps Projects 2021 Alabama Tuskegee, National Forests in Alabama, dates 6/6/2021--8/13/2021, Project Contact: Darrius Truss, [email protected] 404-550-5114 Double Springs, National Forests in Alabama, 6/6/2021--8/13/2021, Project Contact: Shane Hoskins, [email protected] 334-314- 4522 Alaska Juneau, Tongass National Forest / Admiralty Island National Monument, 6/14/2021--8/13/2021 Project Contact: Don MacDougall, [email protected] 907-789-6280 Arizona Douglas, Coronado National Forest, 6/13/2021--7/25/2021, Project Contacts: Doug Ruppel and Brian Stultz, [email protected] and [email protected] 520-388-8438 Prescott, Prescott National Forest, 6/13/2021--7/25/2021, Project Contact: Nina Hubbard, [email protected] 928- 232-0726 Phoenix, Tonto National Forest, 6/7/2021--7/25/2021, Project Contact: Brooke Wheelock, [email protected] 602-225-5257 Arkansas Glenwood, Ouachita National Forest, 6/7/2021--7/30/2021, Project Contact: Bill Jackson, [email protected] 501-701-3570 Mena, Ouachita National Forest, 6/7/2021--7/30/2021, Project Contact: Bill Jackson, [email protected] 501- 701-3570 California Mount Shasta, Shasta Trinity National Forest, 6/28/2021--8/6/2021, Project Contact: Marcus Nova, [email protected] 530-926-9606 Etna, Klamath National Forest, 6/7/2021--7/31/2021, Project Contact: Jeffrey Novak, [email protected] 530-841- 4467 USDA Forest Service Youth Conservation Corps Projects 2021 2 Colorado Grand Junction, Grand Mesa Uncomphagre and Gunnison National Forests, 6/7/2021--8/14/2021 Project Contact: Lacie Jurado, [email protected] 970-817-4053, 2 projects. -

Buckingham Trails Preserve Wildlife Species List

Wildlife Species List for Buckingham Trails Preserve Designated Status Scientific Name Common Name FWC FWS FNAI MAMMALS Family: Dasypodidae (armadillos) Dasypus novemcinctus nine-banded armadillo * Family: Leporidae (rabbits and hares) Sylvilagus floridanus eastern cottontail Family: Felidae (cats) Felis silvestris domestic cat * Family: Procyonidae (raccoons) Procyon lotor raccoon Family: Suidae (old world swine) Sus scrofa feral hog * Family: Mephitidae (skunks) Spilogale putorius eastern spotted skunk BIRDS Family: Anatidae (swans, geese and ducks) Subfamily: Anatinae Aix sponsa wood duck Anas fulvigula mottled duck Family: Odontophoridae (new world quails) Colinus virginianus northern bobwhite Family: Ciconiidae (storks) Mycteria americana wood stork E E G4/S2 Family: Anhingidae (anhingas) Anhinga anhinga anhinga Family: Ardeidae (herons, egrets, bitterns) Ardea herodius great blue heron Ardea alba great egret G5/S4 Egretta thula snowy egret SSC G5/S3 Egretta caerulea little blue heron SSC G5/S4 Egretta tricolor tricolored heron Bubulcus ibis cattle egret Butorides virescens green heron Family: Threskiornithidae (ibises and spoonbills) Subfamily: Threshiornithinae Eudocimus albus white ibis Family: Cathartidae (new world vultures) Coragyps atratus black vulture Cathartes aura turkey vulture Family: Accipitridae (hawks, kites, accipiters, harriers, eagles) Elanoides forficatus swallow-tailed kite G5/S2 Rostrhamus sociabilis plumbeus Everglades snail kite E E G4G5T3Q/S2 Accipiter cooperii Cooper's hawk G5/S3 Hailaeetus leucocephalus