Food Aid Is Not Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

The Eastern Front and the Struggle Against Marginalization

3 The Eastern Front and the Struggle against Marginalization By John Young Copyright The Small Arms Survey Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey The Small Arms Survey is an independent research project located at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, Switzerland. It serves © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International Studies, Geneva 2007 as the principal source of public information on all aspects of small arms and First published in May 2007 as a resource centre for governments, policy-makers, researchers, and activ- ists. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior Established in 1999, the project is supported by the Swiss Federal Depart- permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by ment of Foreign Affairs, and by contributions from the Governments of Bel- law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- gium, Canada, Finland, France, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should United Kingdom. The Survey is also grateful for past and current project-spe- be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. cific support received from Australia, Denmark, and New Zealand. Further Small Arms Survey funding has been provided by the United Nations Development Programme, Graduate Institute of International Studies the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research, the Geneva 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland International Academic Network, and the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining. -

Final Report

Final report July 2017 – April 2018 Wag Himra Zone, Amhara Region Ethiopia ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The nutrition causal analysis Link NCA in Sekota and Dehana woredas, Wag Himra zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia was funded by the European Union. The study was conducted by Link NCA Analysts, Joanne Chui and Lenka Blanárová, under the supervision of study’s focal points: Amelia Lyons and Vincent Veillaud, Deputy Country Directors for Programs, Action Against Hunger, Ethiopia, and Janis Differt, Technical Advisor Food Security and Livelihoods, Action Against Hunger, France, with valuable contributions from the pool of Technical Advisors at Action Against Hunger, France and Action Against Hunger, Ethiopia, namely Celine Soulier, Xuan Phan, Tom Heath and Jogie Abucejo Agbogan. The Link NCA team wishes to express their thanks to all those who have contributed to this study and/or facilitated its development, in particular: To local authorities for their tireless dedication in the fight against undernutrition and their unwavering support over the course of the study; to Mr. Gardie Nigatu Abuye and his team for their absolute availability and support as well as creative troubleshooting during all stages of the study. To all technical experts who attended the Link NCA technical workshops, including the entire team of technical advisors and project managers at Action Against Hunger, Ethiopia, representatives of partner organizations, such as Danish Church Aid, Organization for Rehabilitation & Development in Amhara, Plan International and Save the Children, as well as all dedicated staff representing woreda and zone offices in their respective domains, for sharing their expertise and hence contributing to the high quality of the study. -

Knowledge and Attitude of Pregnant Women Towards Preeclampsia and Its Associated Factors in South Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopi

Mekie et al. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2021) 21:160 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03647-2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Knowledge and attitude of pregnant women towards preeclampsia and its associated factors in South Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: a multi‐center facility‐ based cross‐sectional study Maru Mekie1*, Dagne Addisu1, Minale Bezie1, Abenezer Melkie1, Dejen Getaneh2, Wubet Alebachew Bayih2 and Wubet Taklual3 Abstract Background: Preeclampsia has the greatest impact on maternal mortality which complicates nearly a tenth of pregnancies worldwide. It is one of the top five maternal mortality causes and responsible for 16 % of direct maternal death in Ethiopia. Little is known about the level of knowledge and attitude towards preeclampsia in Ethiopia. This study was designed to assess the knowledge and attitude towards preeclampsia and its associated factors in South Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. Methods: A multicenter facility-based cross-sectional study was implemented in four selected hospitals of South Gondar Zone among 423 pregnant women. Multistage random sampling and systematic random sampling techniques were used to select the study sites and the study participants respectively. Data were entered in EpiData version 3.1 while cleaned and analyzed by Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23. Descriptive and inferential statistics were performed. Adjusted odds ratio with 95 % confidence interval were used to identify the significance of the association between the level of knowledge on preeclampsia and its predictors. Results: In this study, 118 (28.8 %), 120 (29.3 %) of the study participants had good knowledge and a positive attitude towards preeclampsia respectively. The likelihood of having good knowledge on preeclampsia was found to be low among women with no education (AOR = 0.22, 95 % CI (0.06, 0.85)), one antenatal care visit (ANC) (AOR = 0.13, 95 % CI (0.03, 0.59)). -

Background Information Study Tour Ethiopia 2007

Landscape Transformation and Sustainable Development in Ethiopia | downloaded: 13.3.2017 Background information for a study tour through Ethiopia, 4-20 September 2006 University of Bern Institute of Geography https://doi.org/10.7892/boris.71076 2007 source: Cover photographs Left: Digging an irrigation channel near Lake Maybar to substitute missing rain in the drought of 1984/1985. Hans Hurni, 1985. Centre: View of the Simen Mountains from the lowlands in the Simen Mountains National Park. Gudrun Schwilch, 1994. Right: Extreme soil degradation in the Andit Tid area, a research site of the Soil Conservation Research Programme (SCRP). Hans Hurni, 1983. Landscape Transformation and Sustainable Development in Ethiopia Background information for a study tour through Ethiopia, 4-20 September 2006 University of Bern Institute of Geography 2007 3 Impressum © 2007 University of Bern, Institute of Geography, Centre for Development and Environment Concept: Hans Hurni Coordination and layout: Brigitte Portner Contributors: Alemayehu Assefa, Amare Bantider, Berhan Asmamew, Manuela Born, Antonia Eisenhut, Veronika Elgart, Elias Fekade, Franziska Grossenbacher, Christine Hauert, Karl Herweg, Hans Hurni, Kaspar Hurni, Daniel Loppacher, Sylvia Lörcher, Eva Ludi, Melese Tesfaye, Andreas Obrecht, Brigitte Portner, Eduardo Ronc, Lorenz Roten, Michael Rüegsegger, Stefan Salzmann, Solomon Hishe, Ivo Strahm, Andres Strebel, Gianreto Stuppani, Tadele Amare, Tewodros Assefa, Stefan Zingg. Citation: Hurni, H., Amare Bantider, Herweg, K., Portner, B. and H. Veit (eds.). 2007. Landscape Transformation ansd Sustainable Development in Ethiopia. Background information for a study tour through Ethiopia, 4-20 September 2006, compiled by the participants. Centre for Development and Environment, University of Bern, Bern, 321 pp. Available from: www.cde.unibe.ch. -

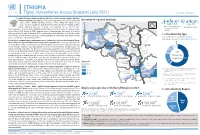

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

International Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatal Health

Prevalence and associated factors of Neonatal near miss among Neonates Born in Hospitals at South Gondar Zone Amhara Region, North West Ethiopia, 2020 International Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatal Health Research Article Volume 5 Issue 1, Prevalence and associated factors of Neonatal near miss among January 2021 Neonates Born in Hospitals at South Gondar Zone Amhara Region, North West Ethiopia, 2020 Copyright ©2021 Adnan Baddour et al. Enyew Dagnew*, Habtamu Geberehana, Minale Bezie, and Abenezer Melkie This is an open access article distributed under the terms of Debre Tabor University, College of Health Sciences, Debre Tabor, Ethiopia the Creative Commons Attri- bution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, Corresponding author: Enyew Dagnew and reproduction in any me- Debre Tabor University, College of Health Sciences, Debre Tabor, Ethiopia. Tel No: 0918321285, dium, provided the original E-mail: [email protected] author andsource are credited. Article History: Received: February 07, 2020; Accepted: February 24, 2020; Published: January 18, 2021. Citation Abstract Enyew Dagnew et al. (2021), Objective: The aim of this study was to determine prevalence and associated factors of neonatal near Features of Bone Mineraliza- miss in Hospitals at South Gondar Zone Amhara Region, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019. tion in Children with Chron- Institutional based cross sectional study was employed among 848 study participants. Data was ic Diseases. Int J Ped & Neo collected with pretested structured questionnaire. The data was entered by Epi-Info version 7 software Heal. 5:1, 10-18 and exported to SPSS version 23 for analysis. Statistical significance was declared at P value of < 0.05. Results: In this study, prevalence of neonatal near miss in the study area were 242 (28.54%) of neonates (95% CI 25.5%, 31.8%). -

Measles Outbreak in Simada District, South Gondar Zone, Amhara

Brief communication Measles outbreak in Simada District, South Gondar Zone, Amhara Region, May - June 2009: Immediate need for strengthened routine and supplemental immunization activities (SIAs) Mer’Awi Aragaw1, Tesfaye Tilay2 Abstract Background: Recently measles outbreaks have been occurring in several areas of Ethiopia. Methods: Desk review of outbreak surveillance data was conducted to identify the susceptible subjects and highly affected groups of the community in Simada District, Amhara Region, May and June, 2009. Results: A total of 97 cases with 13 deaths (Case fatality Rate (CFR) of 13.4%) were reported delayed about 2 weeks. Cases ranged in of age range from 3 months to 79 years, with 43.3% aged 15 years and above; and high age specific attack rate in children under 5 and infants (p-value<0.0001). Conclusion and Recommendation: These findings indicate accumulation of susceptible children under 5 and a need to strengthen both routine and supplemental immunization activities (SIAs) and surveillance, with monitoring of accumulation of susceptible individuals to protect both target and non-target age groups. Surveillance should be extended to and owned by volunteer community health workers and the community, particularly in such remote areas. [Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 2012;26(2):115-118] Introduction outbreaks indicate accumulation of susceptible Measles is a highly infectious viral disease that can cause population for different reasons. permanent disabilities and death. In 1980, before the widespread global use of measles vaccine, an estimated Measles outbreak was reported from Simada District on 2.6 million measles deaths occurred worldwide (1). In 29 May 2009. This study to describes the outbreak and developing countries, serious complications may occur in identifies the susceptible population. -

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010 R Legend Eritrea E Tigray R egion !ª D 450 ho uses burned do wn d ue to th e re ce nt International Boundary !ª !ª Ahferom Sudan Tahtay Erob fire incid ent in Keft a hum era woreda. I nhabitan ts Laelay Ahferom !ª Regional Boundary > Mereb Leke " !ª S are repo rted to be lef t out o f sh elter; UNI CEF !ª Adiyabo Adiyabo Gulomekeda W W W 7 Dalul E !Ò Laelay togethe r w ith the regiona l g ove rnm ent is Zonal Boundary North Western A Kafta Humera Maychew Eastern !ª sup portin g the victim s with provision o f wate r Measle Cas es Woreda Boundary Central and oth er imm ediate n eeds Measles co ntinues to b e re ported > Western Berahle with new four cases in Arada Zone 2 Lakes WBN BN Tsel emt !A !ª A! Sub-city,Ad dis Ababa ; and one Addi Arekay> W b Afa r Region N b Afdera Military Operation BeyedaB Ab Ala ! case in Ahfe rom woreda, Tig ray > > bb The re a re d isplaced pe ople from fo ur A Debark > > b o N W b B N Abergele Erebtoi B N W Southern keb eles of Mille and also five kebeles B N Janam ora Moegale Bidu Dabat Wag HiomraW B of Da llol woreda s (400 0 persons) a ff ected Hot Spot Areas AWD C ases N N N > N > B B W Sahl a B W > B N W Raya A zebo due to flo oding from Awash rive r an d ru n Since t he beg in nin g of th e year, Wegera B N No Data/No Humanitarian Concern > Ziquala Sekota B a total of 967 cases of AWD w ith East bb BN > Teru > off fro m Tigray highlands, respective ly. -

Disability and Its Prevalence and Cause in Northwestern Ethiopia

Disability and its prevalence and cause in northwestern Ethiopia: evidence from Dabat district of Amhara National Regional State: A community based cross-sectional study Solomon Mekonnen Abebe ( [email protected] ) University of Gondar College of Medicine and Health Sciences Ansha Nega Addis Ababa University Zemichel Gizaw University of Gondar College of Medicine and Health Sciences Mulugeta Bayisa University of Gondar College of Medicine and Health Sciences Solomon Fasika University of Gondar College of Medicine and Health Sciences Molalign Belay University of Gondar College of Social Sciences and Humanities Abel Fekadu University of Gondar College of Medicine and Health Sciences Mikyas Abera University of Gondar College of Social Sciences and Humanities Research article Keywords: disability, PwDs, DHSS, household survey, northwestern Ethiopia Posted Date: August 4th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-18602/v3 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/16 Abstract Background Disability is not just a factor of an individual’s physical condition; it develops through human interactions and reects the social fabric of communities. Despite the fact that it directly affects 15% of Ethiopians, understanding and policy-relevant studies on disability and the conditions of persons with disabilities are lacking. The Dabat Demographic and Health Surveillance System part of the response to ll this gap. With signicant drawbacks in the Surveillance System, this study aimed at assessing the prevalence, types and major causes of disability in Dabat district. Method A community-based cross-sectional study design was employed and covered 17,000 households residing in 13 Kebeles of Dabat district. -

Final Report1

PROJECT REPORT To: Austrian Development Agency NGO Cooperation and Humanitarian Aid Zelinkagasse 2, 1010 Vienna E-mail: [email protected] Project progress reports are to be presented by e-mail as contractually agreed. Originals of additional documents can be sent to the NGO Cooperation desk. Final Report1 Contract number: 2679-00/2016 Contract partner in Austria Local project partner Name: Name: CARE Österreich CARE Ethiopia Address: Address: Lange Gasse 30/4, 1080 Vienna, Austria Telephone, e-mail: Telephone, e-mail: +43 1 715 0 715 +251 911 237 582 [email protected] +251911819687 Project officer/contact: Project officer/contact: Stéphanie Bouriel Teyent Taddesse [email protected] [email protected] Worku Abebaw [email protected] Project title: Emergency Seed Support to Smallholder Drought- Affected Farmers in South Gondar Ethiopia Country: Ethiopia Region/place: Amhara /South Gondar Duration from: 29 Feb 2016 to: 30 November 2016 Report as at (date):November 30, 2016 submitted on: March 7, 2017 Invoicing as at (date) in euros Submitted for Total project costs Invoiced to date Outstanding verification as at (date) 430,000 EURO 424,598.14 EURO 424.598,14 EURO 5.401,86 Date, report written by CARE Ethiopia, February 2017 1 Delete as applicable NGO individual projects– version: January 2009 | 1 PROJECT REPORT 1. Brief description of project progress2 (German, max. 1 page) A drought due to the effect of El Niño phenomenon had impacted 10.2 million people in various regions of Ethiopia. South Gonder administrative zone located in Amhara region and comprising seven livelihood zones, was amongst the areas most affected. -

Modeling Malaria Cases Associated with Environmental Risk Factors in Ethiopia Using Geographically Weighted Regression

MODELING MALARIA CASES ASSOCIATED WITH ENVIRONMENTAL RISK FACTORS IN ETHIOPIA USING GEOGRAPHICALLY WEIGHTED REGRESSION Berhanu Berga Dadi i MODELING MALARIA CASES ASSOCIATED WITH ENVIRONMENTAL RISK FACTORS IN ETHIOPIA USING THE GEOGRAPHICALLY WEIGHTED REGRESSION MODEL, 2015-2016 Dissertation supervised by Dr.Jorge Mateu Mahiques,PhD Professor, Department of Mathematics University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain Ana Cristina Costa, PhD Professor, Nova Information Management School University of Nova Lisbon, Portugal Pablo Juan Verdoy, PhD Professor, Department of Mathematics University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain March 2020 ii DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that the work described in this document is my own and not from someone else. All the assistance I have received from other people is duly acknowledged, and all the sources (published or not published) referenced. This work has not been previously evaluated or submitted to the University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain, or elsewhere. Castellon, 30th Feburaury 2020 Berhanu Berga Dadi iii Acknowledgments Before and above anything, I want to thank our Lord Jesus Christ, Son of GOD, for his blessing and protection to all of us to live. I want to thank also all consortium of Erasmus Mundus Master's program in Geospatial Technologies for their financial and material support during all period of my study. Grateful acknowledgment expressed to Supervisors: Prof.Dr.Jorge Mateu Mahiques, Universitat Jaume I(UJI), Prof.Dr.Ana Cristina Costa, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, and Prof.Dr.Pablo Juan Verdoy, Universitat Jaume I(UJI) for their immense support, outstanding guidance, encouragement and helpful comments throughout my thesis work. Finally, but not least, I would like to thank my lovely wife, Workababa Bekele, and beloved daughter Loise Berhanu and son Nethan Berhanu for their patience, inspiration, and understanding during the entire period of my study.