Dissolving Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slum Clearance in Havana in an Age of Revolution, 1930-65

SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 by Jesse Lewis Horst Bachelor of Arts, St. Olaf College, 2006 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jesse Horst It was defended on July 28, 2016 and approved by Scott Morgenstern, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Edward Muller, Professor, Department of History Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History Co-Chair: George Reid Andrews, Distinguished Professor, Department of History Co-Chair: Alejandro de la Fuente, Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin American History and Economics, Department of History, Harvard University ii Copyright © by Jesse Horst 2016 iii SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 Jesse Horst, M.A., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This dissertation examines the relationship between poor, informally housed communities and the state in Havana, Cuba, from 1930 to 1965, before and after the first socialist revolution in the Western Hemisphere. It challenges the notion of a “great divide” between Republic and Revolution by tracing contentious interactions between technocrats, politicians, and financial elites on one hand, and mobilized, mostly-Afro-descended tenants and shantytown residents on the other hand. The dynamics of housing inequality in Havana not only reflected existing socio- racial hierarchies but also produced and reconfigured them in ways that have not been systematically researched. -

TULSA METROPOLITAN AREA PLANNING COMMISSION Minutes of Meeting No

TULSA METROPOLITAN AREA PLANNING COMMISSION Minutes of Meeting No. 2646 Wednesday, March 20, 2013, 1:30 p.m. City Council Chamber One Technology Center – 175 E. 2nd Street, 2nd Floor Members Present Members Absent Staff Present Others Present Covey Stirling Bates Tohlen, COT Carnes Walker Fernandez VanValkenburgh, Legal Dix Huntsinger Warrick, COT Edwards Miller Leighty White Liotta Wilkerson Midget Perkins Shivel The notice and agenda of said meeting were posted in the Reception Area of the INCOG offices on Monday, March 18, 2013 at 2:10 p.m., posted in the Office of the City Clerk, as well as in the Office of the County Clerk. After declaring a quorum present, 1st Vice Chair Perkins called the meeting to order at 1:30 p.m. REPORTS: Director’s Report: Ms. Miller reported on the TMAPC Receipts for the month of February 2013. Ms. Miller submitted and explained the timeline for the general work program for 6th Street Infill Plan Amendments and Form-Based Code Revisions. Ms. Miller reported that the TMAPC website has been improved and should be online by next week. Mr. Miller further reported that there will be a work session on April 3, 2013 for the Eugene Field Small Area Plan immediately following the regular TMAPC meeting. * * * * * * * * * * * * 03:20:13:2646(1) CONSENT AGENDA All matters under "Consent" are considered by the Planning Commission to be routine and will be enacted by one motion. Any Planning Commission member may, however, remove an item by request. 1. LS-20582 (Lot-Split) (CD 3) – Location: Northwest corner of East Apache Street and North Florence Avenue (Continued from 3/6/2013) 1. -

Managing Metropolitan Growth: Reflections on the Twin Cities Experience

_____________________________________________________________________________________________ MANAGING METROPOLITAN GROWTH: REFLECTIONS ON THE TWIN CITIES EXPERIENCE Ted Mondale and William Fulton A Case Study Prepared for: The Brookings Institution Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy © September 2003 _____________________________________________________________________________________________ MANAGING METROPOLITAN GROWTH: REFLECTIONS ON THE TWIN CITIES EXPERIENCE BY TED MONDALE AND WILLIAM FULTON1 I. INTRODUCTION: MANAGING METROPOLITAN GROWTH PRAGMATICALLY Many debates about whether and how to manage urban growth on a metropolitan or regional level focus on the extremes of laissez-faire capitalism and command-and-control government regulation. This paper proposes an alternative, or "third way," of managing metropolitan growth, one that seeks to steer in between the two extremes, focusing on a pragmatic approach that acknowledges both the market and government policy. Laissez-faire advocates argue that we should leave growth to the markets. If the core cities fail, it is because people don’t want to live, shop, or work there anymore. If the first ring suburbs decline, it is because their day has passed. If exurban areas begin to choke on large-lot, septic- driven subdivisions, it is because that is the lifestyle that people individually prefer. Government policy should be used to accommodate these preferences rather than seek to shape any particular regional growth pattern. Advocates on the other side call for a strong regulatory approach. Their view is that regional and state governments should use their power to engineer precisely where and how local communities should grow for the common good. Among other things, this approach calls for the creation of a strong—even heavy-handed—regional boundary that restricts urban growth to particular geographical areas. -

Letter Bill 0..3

HB0939 *LRB10103319AWJ48327b* 101ST GENERAL ASSEMBLY State of Illinois 2019 and 2020 HB0939 by Rep. Michael J. Madigan SYNOPSIS AS INTRODUCED: 65 ILCS 5/1-1-2 from Ch. 24, par. 1-1-2 Amends the Illinois Municipal Code. Makes a technical change in a Section concerning definitions. LRB101 03319 AWJ 48327 b A BILL FOR HB0939 LRB101 03319 AWJ 48327 b 1 AN ACT concerning local government. 2 Be it enacted by the People of the State of Illinois, 3 represented in the General Assembly: 4 Section 5. The Illinois Municipal Code is amended by 5 changing Section 1-1-2 as follows: 6 (65 ILCS 5/1-1-2) (from Ch. 24, par. 1-1-2) 7 Sec. 1-1-2. Definitions. In this Code: 8 (1) "Municipal" or "municipality" means a city, village, or 9 incorporated town in the the State of Illinois, but, unless the 10 context otherwise provides, "municipal" or "municipality" does 11 not include a township, town when used as the equivalent of a 12 township, incorporated town that has superseded a civil 13 township, county, school district, park district, sanitary 14 district, or any other similar governmental district. If 15 "municipal" or "municipality" is given a different definition 16 in any particular Division or Section of this Act, that 17 definition shall control in that division or Section only. 18 (2) "Corporate authorities" means (a) the mayor and 19 aldermen or similar body when the reference is to cities, (b) 20 the president and trustees or similar body when the reference 21 is to villages or incorporated towns, and (c) the council when 22 the reference is to municipalities under the commission form of 23 municipal government. -

Town Tree Cover in Bridgend County Borough

1 Town Tree Cover in Bridgend County Borough Understanding canopy cover to better plan and manage our urban trees 2 Foreword Introducing a world-first for Wales is a great pleasure, particularly as it relates to greater knowledge about the hugely valuable woodland and tree resource in our towns and cities. We are the first country in the world to have undertaken a country-wide urban canopy cover survey. The resulting evidence base set out in this supplementary county specific study for Bridgend County Borough will help all of us - from community tree interest groups to urban planners and decision-makers in local Emyr Roberts Diane McCrea authorities and our national government - to understand what we need to do to safeguard this powerful and versatile natural asset. Trees are an essential component of our urban ecosystems, delivering a range of services to help sustain life, promote well-being, and support economic benefits. They make our towns and cities more attractive to live in - encouraging inward investment, improving the energy efficiency of buildings – as well as removing air borne pollutants and connecting people with nature. They can also mitigate the extremes of climate change, helping to reduce storm water run-off and the urban heat island. Natural Resources Wales is committed to working with colleagues in the Welsh Government and in public, third and private sector organisations throughout Wales, to build on this work and promote a strategic approach to managing our existing urban trees, and to planting more where they will -

GAO-04-758 Metropolitan Statistical Areas

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Subcommittee on GAO Technology, Information Policy, Intergovernmental Relations and the Census, Committee on Government Reform, House of Representatives June 2004 METROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREAS New Standards and Their Impact on Selected Federal Programs a GAO-04-758 June 2004 METROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREAS New Standards and Their Impact on Highlights of GAO-04-758, a report to the Selected Federal Programs Subcommittee on Technology, Information Policy, Intergovernmental Relations and the Census, Committee on Government Reform, House of Representatives For the past 50 years, the federal The new standards for federal statistical recognition of metropolitan areas government has had a metropolitan issued by OMB in 2000 differ from the 1990 standards in many ways. One of the area program designed to provide a most notable differences is the introduction of a new designation for less nationally consistent set of populated areas—micropolitan statistical areas. These are areas comprised of a standards for collecting, tabulating, central county or counties with at least one urban cluster of at least 10,000 but and publishing federal statistics for geographic areas in the United fewer than 50,000 people, plus adjacent outlying counties if commuting criteria States and Puerto Rico. Before is met. each decennial census, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) The 2000 standards and the latest population update have resulted in five reviews the standards to ensure counties being dropped from metropolitan statistical areas, while another their continued usefulness and 41counties that had been a part of a metropolitan statistical area have had their relevance and, if warranted, revises statistical status changed and are now components of micropolitan statistical them. -

Urbanistica N. 146 April-June 2011

Urbanistica n. 146 April-June 2011 Distribution by www.planum.net Index and english translation of the articles Paolo Avarello The plan is dead, long live the plan edited by Gianfranco Gorelli Urban regeneration: fundamental strategy of the new structural Plan of Prato Paolo Maria Vannucchi The ‘factory town’: a problematic reality Michela Brachi, Pamela Bracciotti, Massimo Fabbri The project (pre)view Riccardo Pecorario The path from structure Plan to urban design edited by Carla Ferrari A structural plan for a ‘City of the wine’: the Ps of the Municipality of Bomporto Projects and implementation Raffaella Radoccia Co-planning Pto in the Val Pescara Mariangela Virno Temporal policies in the Abruzzo Region Stefano Stabilini, Roberto Zedda Chronographic analysis of the Urban systems. The case of Pescara edited by Simone Ombuen The geographical digital information in the planning ‘knowledge frameworks’ Simone Ombuen The european implementation of the Inspire directive and the Plan4all project Flavio Camerata, Simone Ombuen, Interoperability and spatial planners: a proposal for a land use Franco Vico ‘data model’ Flavio Camerata, Simone Ombuen What is a land use data model? Giuseppe De Marco Interoperability and metadata catalogues Stefano Magaudda Relationships among regional planning laws, ‘knowledge fra- meworks’ and Territorial information systems in Italy Gaia Caramellino Towards a national Plan. Shaping cuban planning during the fifties Profiles and practices Rosario Pavia Waterfrontstory Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Monica Bocci Brasilia, the city of the future is 50 years old. The urban design and the challenges of the Brazilian national capital Michele Talia To research of one impossible balance Antonella Radicchi On the sonic image of the city Marco Barbieri Urban grapes. -

The Blitz and Its Legacy

THE BLITZ AND ITS LEGACY 3 – 4 SEPTEMBER 2010 PORTLAND HALL, LITTLE TITCHFIELD STREET, LONDON W1W 7UW ABSTRACTS Conference organised by Dr Mark Clapson, University of Westminster Professor Peter Larkham, Birmingham City University (Re)planning the Metropolis: Process and Product in the Post-War London David Adams and Peter J Larkham Birmingham City University [email protected] [email protected] London, by far the UK’s largest city, was both its worst-damaged city during the Second World War and also was clearly suffering from significant pre-war social, economic and physical problems. As in many places, the wartime damage was seized upon as the opportunity to replan, sometimes radically, at all scales from the City core to the county and region. The hierarchy of plans thus produced, especially those by Abercrombie, is often celebrated as ‘models’, cited as being highly influential in shaping post-war planning thought and practice, and innovative. But much critical attention has also focused on the proposed physical product, especially the seductively-illustrated but flawed beaux-arts street layouts of the Royal Academy plans. Reconstruction-era replanning has been the focus of much attention over the past two decades, and it is appropriate now to re-consider the London experience in the light of our more detailed knowledge of processes and plans elsewhere in the UK. This paper therefore evaluates the London plan hierarchy in terms of process, using new biographical work on some of the authors together with archival research; product, examining exactly what was proposed, and the extent to which the different plans and different levels in the spatial planning hierarchy were integrated; and impact, particularly in terms of how concepts developed (or perhaps more accurately promoted) in the London plans influenced subsequent plans and planning in the UK. -

An Economist's Perspective on Urban Sprawl, Part 1, Defining Excessive

An Economist’s Perspective on Urban Sprawl, Part 1 An Economist’s Perspective on Urban Sprawl, Part 1 Defining Excessive Decentralization in California and Other Western States California Senate Office of Research January 2002 (Revised) An Economist’s Perspective on Urban Sprawl, Part 1 An Economist’s Perspective on Urban Sprawl, Part I Defining Excessive Decentralization in California and Other Western States Prepared by Robert W. Wassmer Professor Graduate Program in Public Policy and Administration California State University Visiting Consultant California Senate Office of Research Support for this work came from the California Institute for County Government, Capital Regional Institute and Valley Vision, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, and the California State University Faculty Research Fellows in association with the California Senate Office of Research. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author. Senate Office of Research Elisabeth Kersten, Director Edited by Rebecca LaVally and formatted by Lynne Stewart January 2002 (Revised) 2 An Economist’s Perspective on Urban Sprawl, Part 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary..................................................................................... 4 What is Sprawl? ........................................................................................... 5 Findings ........................................................................................................ 5 Conclusions.................................................................................................. -

Warwickshire County Record Office

WARWICKSHIRE COUNTY RECORD OFFICE Priory Park Cape Road Warwick CV34 4JS Tel: (01926) 738959 Email: [email protected] Website: http://heritage.warwickshire.gov.uk/warwickshire-county-record-office Please note we are closed to the public during the first full week of every calendar month to enable staff to catalogue collections. A full list of these collection weeks is available on request and also on our website. The reduction in our core funding means we can no longer produce documents between 12.00 and 14.15 although the searchroom will remain open during this time. There is no need to book an appointment, but entry is by CARN ticket so please bring proof of name, address and signature (e.g. driving licence or a combination of other documents) if you do not already have a ticket. There is a small car park with a dropping off zone and disabled spaces. Please telephone us if you would like to reserve a space or discuss your needs in any detail. Last orders: Documents/Photocopies 30 minutes before closing. Transportation to Australia and Tasmania Transportation to Australia began in 1787 with the sailing of the “First Fleet” of convicts and their arrival at Botany Bay in January 1788. The practice continued in New South Wales until 1840, in Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania) until 1853 and in Western Australia until 1868. Most of the convicts were tried at the Assizes, The Court of the Assize The Assizes dealt with all cases where the defendant was liable to be sentenced to death (nearly always commuted to transportation for life. -

Historic Preservation in Sherborn

HISTORIC PRESERVATION IN SHERBORN I. Town Facts and Brief History A. Town Facts Sherborn is a small semi-rural community located about 18 miles southwest of Boston. The town is proud of its rural heritage which is still evident in many active farms and orchards, and preserved in Town Forest and other extensive public lands. Open space comprises more than 50% of the town's area. Because all properties have individual wells and septic systems, minimum house lot sizes are one, two or three acres, depending upon location. Sherborn is an active, outdoors-oriented town where residents enjoy miles of trails through woods and meadows for walking and horseback riding, swim and boat in Farm Pond, and participate in any number of team sports. A high degree of volunteerism due to strong citizen support for town projects, and commitment to excellence in public education, characterize the community's values today, as they have for more than 325 years. Some quick facts about Sherborn are: Total Area: 16.14 sq. miles (10328 acres) Land Area: 15.96 sq. miles (10214 acres) Population: 4,545 (12/31/02) Registered voters: 2,852 (12/31/02) Total Residences 1,497 (1/1/02) Single family homes: 1,337 (1/1/02) Avg. single family tax bill: $8,996 (FY03) B. Brief History Of Sherborn Settled in 1652 and incorporated in 1674, Sherborn was primarily a farming community until the early part of the 20th century. It now is a bedroom town for Boston and the surrounding hi-tech area. Sherborn's original land area encompassed the present territory of Holliston, Ashland, and parts of Mendon, Framingham and Natick. -

CPY Document

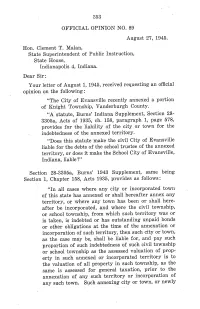

353 OFFICIAL OPINION NO. 89 August 27, 1945. Hon. Clement T. Malan, State Superintendent of Public Instruction, State House, Indianapolis 4, Indiana. Dear Sir: Your letter of August 1, 1945, received requesting an offcial opinion on the following: "The City of Evansvile recently annexed a portion of Knight Township, Vanderburgh County. "A statute, Burns' Indiana Supplement, Section 28- 3305a, Acts of 1935, ch. 158, paragraph 1, page 578, provides for the liabilty of the city or town for the indebtedness of the annexed territory. "Does this statute make the civil City of Evansvile liable for the debts of the school trustee of the annexed territory, or does it make the School City of Evansvile, Indiana, liable?" Section 28-3305a, Burns' 1943 Supplement, saine being Section 1, Chapter 158, Acts 1935, provides as follows: "In all cases where any city or incorporated town of this state has annexed or shall hereafter annex any territory, or where any town has been or shall here- after be incorporated, and where the civil township, or school township, from which such territory was or is taken, is indebted or has outstanding unpaid bonds or other obligations at the time of the annexation or incorporation of such territory, then such city or town, as the case mày be, shall be liable for, and pay such proportion of such indebtedness of such civil township or school township as the assessed valuation of prop- erty in such annexed or incorporated territory is to the valuation of all property in such township, as the same is assessed for general taxation, prior to the annexation of any such territory or incorporation of any such town.