In Search of Nationalist Trends in Indian Anthropology: Opening a New Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-Kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L

Western Washington University Western CEDAR A Collection of Open Access Books and Books and Monographs Monographs 2008 Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L. Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David L., "Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal" (2008). A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books and Monographs at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Acknowledgements. 1. A Historian’s Introduction to Reading Mangal-Kabya. 2. Kings and Commerce on an Agrarian Frontier: Kalketu’s Story in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 3. Marriage, Honor, Agency, and Trials by Ordeal: Women’s Gender Roles in Candimangal. 4. ‘Tribute Exchange’ and the Liminality of Foreign Merchants in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 5. ‘Voluntary’ Relationships and Royal Gifts of Pan in Mughal Bengal. 6. Maharaja Krsnacandra, Hinduism and Kingship in the Contact Zone of Bengal. 7. Lost Meanings and New Stories: Candimangal after British Dominance. Index. Acknowledgements This collection of essays was made possible by the wonderful, multidisciplinary education in history and literature which I received at the University of Chicago. It is a pleasure to thank my living teachers, Herman Sinaiko, Ronald B. -

Annual Report 2014 - 2015 Ministry of Culture Government of India

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 - 2015 MINISTRY OF CULTURE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Annual Report 2014-15 1 Ministry of Culture 2 Detail from Rani ki Vav, Patan, Gujarat, A World Heritage Site Annual Report 2014-15 CONTENTS 1. Ministry of Culture - An Overview – 5 2. Tangible Cultural Heritage 2.1 Archaeological Survey of India – 11 2.2 Museums – 28 2.2a National Museum – 28 2.2b National Gallery of Modern Art – 31 2.2c Indian Museum – 37 2.2d Victoria Memorial Hall – 39 2.2e Salar Jung Museum – 41 2.2f Allahabad Museum – 44 2.2g National Council of Science Museum – 46 2.3 Capacity Building in Museum related activities – 50 2.3a National Museum Institute of History of Art, Conservation and Museology – 50 2.3.b National Research Laboratory for conservation of Cultural Property – 51 2.4 National Culture Fund (NCF) – 54 2.5 International Cultural Relations (ICR) – 57 2.6 UNESCO Matters – 59 2.7 National Missions – 61 2.7a National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities – 61 2.7b National Mission for Manuscripts – 61 2.7c National Mission on Libraries – 64 2.7d National Mission on Gandhi Heritage Sites – 65 3. Intangible Cultural Heritage 3.1 National School of Drama – 69 3.2 Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts – 72 3.3 Akademies – 75 3.3a Sahitya Akademi – 75 3.3b Lalit Kala Akademi – 77 3.3c Sangeet Natak Akademi – 81 3.4 Centre for Cultural Resources and Training – 85 3.5 Kalakshetra Foundation – 90 3.6 Zonal cultural Centres – 94 3.6a North Zone Cultural Centre – 95 3.6b Eastern Zonal Cultural Centre – 95 3.6c South Zone Cultural Centre – 96 3.6d West Zone Cultural Centre – 97 3.6e South Central Zone Cultural Centre – 98 3.6f North Central Zone Cultural Centre – 98 3.6g North East Zone Cultural Centre – 99 Detail from Rani ki Vav, Patan, Gujarat, A World Heritage Site 3 Ministry of Culture 4. -

The Pakistan, India, and China Triangle

India frequently experience clashes The Pakistan, along their shared borders, espe- cially on the de facto border of Pa- India, and kistan-administered and India-ad- 3 ministered Kashmir.3 China Triangle Pakistan’s Place in The triangular relationship be- the Sino-Indian tween India, China, and Pakistan is of critical importance to regional Border Dispute and global stability.4 Managing the Dr. Maira Qaddos relationship is an urgent task. Yet, the place of Pakistan in the trian- gular relationship has sometimes gone overlooked. When India and China were embroiled in the recent military standoff at the Line of Ac- tual Control (LAC), Pakistan was mentioned only because of an ex- pectation (or fear) that Islamabad would exploit the situation to press its interests in Kashmir. At that time, the Indian-administered por- tion of Kashmir had been experi- t is quite evident from the history encing lockdowns and curfews for of Pakistan’s relationship with months, raising expectations that I China that Pakistan views Sino- Pakistan might raise the tempera- Indian border disputes through a ture. But although this insight Chinese lens. This is not just be- (that the Sino-Indian clashes cause of Pakistani-Chinese friend- would affect Pakistan’s strategic ship, of course, but also because of interests) was correct, it was in- the rivalry and territorial disputes complete. The focus should not that have marred India-Pakistan have been on Pakistani opportun- relations since their independ- ism, which did not materialize, but ence.1 Just as China and India on the fundamental interconnect- have longstanding disputes that edness that characterizes the led to wars in the past (including, South Asian security situation—of recently, the violent clashes in the which Sino-Indian border disputes Galwan Valley in May-June are just one part. -

Special Bulletin Remembering Mahatma Gandhi

Special Bulletin Remembering Mahatma Gandhi Dear Members and Well Wishers Let me convey, on behalf of the Council of the Asiatic Society, our greetings and good wishes to everybody on the eve of the ensuing festivals in different parts of the country. I take this opportunity to share with you the fact that as per the existing convention Ordinary Monthly Meeting of the members is not held for two months, namely October and November. Eventually, the Monthly Bulletin of the Society is also not published and circulated. But this year being the beginning of 150 years of Birth Anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, the whole nation is up on its toes to celebrate the occasion in the most befitting manner. The Government of India has taken major initiatives to commemorate this eventful moment through its different ministries. As a consequence, the Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India, has followed it up with directives to various departments and institutions-attached, subordinate, all autonomous bodies including the Asiatic Society, under its control for taking up numerous academic programmes. The Asiatic Society being the oldest premier institution of learning in whole of this continent, which has already been declared as an Institution of National Importance since 1984 by an Act of the Parliament, Govt. of India, has committed itself to organise a number of programmes throughout the year. These programmes Include (i) holding of a National Seminar with leading academicians who have been engaged in the cultivation broadly on the life and activities (including the basic philosophical tenets) of Mahatma Gandhi, (ii) reprinting of a book entitled Studies in Gandhism (1940) written and published by late Professor Nirmal Kumar Bose (1901-1972), and (iii) organizing a series of monthly lectures for coming one year. -

Indian Anthropology

INDIAN ANTHROPOLOGY HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN INDIA Dr. Abhik Ghosh Senior Lecturer, Department of Anthropology Panjab University, Chandigarh CONTENTS Introduction: The Growth of Indian Anthropology Arthur Llewellyn Basham Christoph Von-Fuhrer Haimendorf Verrier Elwin Rai Bahadur Sarat Chandra Roy Biraja Shankar Guha Dewan Bahadur L. K. Ananthakrishna Iyer Govind Sadashiv Ghurye Nirmal Kumar Bose Dhirendra Nath Majumdar Iravati Karve Hasmukh Dhirajlal Sankalia Dharani P. Sen Mysore Narasimhachar Srinivas Shyama Charan Dube Surajit Chandra Sinha Prabodh Kumar Bhowmick K. S. Mathur Lalita Prasad Vidyarthi Triloki Nath Madan Shiv Raj Kumar Chopra Andre Beteille Gopala Sarana Conclusions Suggested Readings SIGNIFICANT KEYWORDS: Ethnology, History of Indian Anthropology, Anthropological History, Colonial Beginnings INTRODUCTION: THE GROWTH OF INDIAN ANTHROPOLOGY Manu’s Dharmashastra (2nd-3rd century BC) comprehensively studied Indian society of that period, based more on the morals and norms of social and economic life. Kautilya’s Arthashastra (324-296 BC) was a treatise on politics, statecraft and economics but also described the functioning of Indian society in detail. Megasthenes was the Greek ambassador to the court of Chandragupta Maurya from 324 BC to 300 BC. He also wrote a book on the structure and customs of Indian society. Al Biruni’s accounts of India are famous. He was a 1 Persian scholar who visited India and wrote a book about it in 1030 AD. Al Biruni wrote of Indian social and cultural life, with sections on religion, sciences, customs and manners of the Hindus. In the 17th century Bernier came from France to India and wrote a book on the life and times of the Mughal emperors Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, their life and times. -

Bulletin of the Ramaltrishna Mission Institute of Culture

Single copy: { l0 Bulletin of the Ramaltrishna Mission Institute of Culture SE,pTEMBER 2O2O rssN 0971-2755 * Vor. LXXI No.9 * GOL PARK * KOLKATA 7OOO29 Bulletin of the Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture Editor SWAMI SUPARNANANDA '\'i0t oJlt''>r Associate Editor r TIRTHANKAR DAS PURKAYASTHA Vor-urr,lr. LXXI SEPTEMBER 2O2O NuHassn * OBSERVATIONS On Enemies And Allies 4 * SAYINGS Akhanclanancla " 5 -swanti * RELIGION AND PHILOSOPHY Law of Karmo--Jhe Saving Grace K. Sarkar 6 -Bid.v-ut * PHILOSOPHY AND SCIENCE Prdna Kuntar Laha 13 -Arun * AROUNDTHEWORLD The Ramakrishna Movement in the West : Contribution of Some of Its Pioneer Swamis (1920-70FXl 17 -sihato.sh Bagchi * FORGETNOT ln Search of a Nationalist Anthropology in India Guha ... 21 -Abhilit * LANGUAGEANDLITERATURE Keats's 'Ode to a Nightingale': A Study of the Manuscript Rolt 23 -Anuraclha Kalam, the Poet's Concept of HarmonY 3l -Asit Kuntar Ciri * WELLBEING Holistic Living: Hidden Treasure of Life Agrawal Y -Lalita * THEARTS At Play with Ramakrishna-A Drama Based on the Life of Sri Ramakrishna-Xl ika Shucldhatntaprana "' 38 -Pravraj The Institute is not necessarily in agreement with the views of contributors to whom fieedom of expression is given. 225- Life subscription (20 ),ears-,Janrru)t to December): India { 1.0001 Other countries $ 300 I f Annual sutrscription (Jarutary to December): India { 100; Other countries $ 27 / f 18. FORGET NOT In Search of a Nationalist Anthropology in India ABHIJIT GUHA Introduction As earl1, as 1952 Nirrnal Kttmar Bose (a esearch on the history of doyen of Indian authropology) in a I significant article errtitled'Current Research "fJ, " Projects in Indian Arrthropology' published ra#y':ff ' [,i::' #"T Ji"" I become a formidable tradition. -

Effects of a Combined Enrichment Intervention on the Behavioural and Physiological Welfare Of

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.24.265686; this version posted August 25, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Effects of a combined enrichment intervention on the behavioural and physiological welfare of 2 captive Asiatic lions (Panthera leo persica) 3 4 Sitendu Goswami1*, Shiv Kumari Patel1, Riyaz Kadivar2, Praveen Chandra Tyagi1, Pradeep 5 Kumar Malik1, Samrat Mondol1* 6 7 1 Wildlife Institute of India, Chandrabani, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India. 8 2 Sakkarbaug Zoological Garden, Junagadh, Gujarat, India 9 10 11 12 * Corresponding authors: Samrat Mondol, Ph.D., Animal Ecology and Conservation Biology 13 Department, Wildlife Institute of India, Chandrabani, Dehradun, Uttarakhand 248001. Email- 14 [email protected] 15 Sitendu Goswami, Wildlife Institute of India, Chandrabani, Dehradun, Uttarakhand 248001. 16 Email- [email protected] 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Running head: Impacts of enrichment on Asiatic lions. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.24.265686; this version posted August 25, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 24 Abstract 25 The endangered Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica) is currently distributed as a single wild 26 population of 670 individuals and ~400 captive animals globally. -

Decentralised Composting in Bangladesh, a Win-Win Situation for All Stakeholders

Resources, Conservation and Recycling 43 (2005) 281–292 Decentralised composting in Bangladesh, a win-win situation for all stakeholders Christian Zurbrugg¨ a,∗,1, Silke Dreschera,1, Isabelle Rytza,1, A.H.Md. Maqsood Sinhab,2, Iftekhar Enayetullahb,2 a Swiss Federal Institute of Environmental Science and Technology (EAWAG), Department of Water and Sanitation in Developing Countries (SANDEC), P.O. Box 611, 8600 Duebendorf, Switzerland b WASTE CONCERN, House 21 (Side B), Road-7, Block-G, Banani Model Town, Dhaka-1213, Bangladesh Received 13 May 2003; accepted 16 June 2004 Abstract The paper describes experiences of Waste Concern, a research based Non-Governmental Organ- isation, with a community-based decentralised composting project in Mirpur, Dhaka, Bangladesh. The composting scheme started its activities in 1995 with the aim of developing a low-cost technique for composting of municipal solid waste, which is well-suited to Dhaka’s waste stream, climate, and socio-economic conditions along with the development of public–private–community partnerships in solid waste management and creation of job opportunities for the urban poor. Organic waste is converted into compost using the “Indonesian Windrow Technique”, a non-mechanised aerobic and thermophile composting procedure. In an assessment study conducted in 2001, key information on the Mirpur composting scheme was collected. This includes a description of the technical and operational aspects of the composting scheme (site-layout, process steps, mass flows, monitoring of physical and chemical parameters), the evaluation of financial parameters, and the description of the compost marketing strategy. The case study shows a rare successful decentralised collection and composting scheme in a large city of the developing world. -

2-Gayatri Bhattacharyya.Pmd

Gayatri Bhattacharyya INTERROGATING THE CIVILIZATIONAL APPROACH OF N. K. BOSE Nirmal Kumar Bose figures prominently in any discourse on the development of anthropology and sociology in India, serious or popular (Mukherjee, 1977 and 1979; Uberoi, et al., 2007; Nagla, 2008). Ramkrishna Mukherjee admires that Bose did not confine his attention to only one or two aspects of society or to any ‘fashionable’ approach, although he was gently influenced by the American ‘diffusionists’ and Malinowski (1979 : 69). Bose encouraged the younger generation of the 1950s to undertake a meticulous collection of field data, “albeit in micro situations and on the basis of a simplistic methodology”. He did not appear, to Mukherjee, a rigorous and systematic analyst so that “ultimately most of his studies leaned towards enlightened scientific journalism” (1979 : 69). In contrast to the above appraisal of Bose by Mukherjee, Surajit Sinha sought to bring into relief the extraordinary range of intellectual interests of Professor Bose and also how he brought an “original and penetrating mind” to the areas of enquiry of his choice. Bose transgressed the boundaries of specific disciplines and “the conventional divide between theoretical thinking and the application of knowledge”, between social sciences and humanities. He was in search of roots of the perennial “strength of Indian Civilisation” and the factors that constrained its creativity in modern times (Sinha, 1986 : Foreword). The approach adopted by Bose is termed “civilizational” approach (UGC NET syllabus 2000; Chaudhury, 2007; Nagla 2008; Bhattacharya, 2011). Surajit Sinha is viewed to have continued the tradition of Bose (Chaudhuri, 2007, Nagla, 2008). Chaudhury relies in his analysis a great deal on André Béteille who writes, “Fairly early in his career Bose recognised the enormous scale in both space and time of Hindu civilization to go beyond the approaches followed by the anthropologists in their studies of tribal communities. -

12 Manogaran.Pdf

Ethnic Conflict and Reconciliation in Sri Lanka National Capilal District Boundarl3S * Province Boundaries Q 10 20 30 010;1)304050 Sri Lanka • Ethnic Conflict and Reconciliation in Sri Lanka CHELVADURAIMANOGARAN MW~1 UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS • HONOLULU - © 1987 University ofHawaii Press All Rights Reserved Manufactured in the United States ofAmerica Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-Publication-Data Manogaran, Chelvadurai, 1935- Ethnic conflict and reconciliation in Sri Lanka. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Sri Lanka-Politics and government. 2. Sri Lanka -Ethnic relations. 3. Tamils-Sri Lanka-Politics and government. I. Title. DS489.8.M36 1987 954.9'303 87-16247 ISBN 0-8248-1116-X • The prosperity ofa nation does not descend from the sky. Nor does it emerge from its own accord from the earth. It depends upon the conduct ofthe people that constitute the nation. We must recognize that the country does not mean just the lifeless soil around us. The country consists ofa conglomeration ofpeople and it is what they make ofit. To rectify the world and put it on proper path, we have to first rec tify ourselves and our conduct.... At the present time, when we see all over the country confusion, fear and anxiety, each one in every home must con ., tribute his share ofcool, calm love to suppress the anger and fury. No governmental authority can sup press it as effectively and as quickly as you can by love and brotherliness. SATHYA SAl BABA - • Contents List ofTables IX List ofFigures Xl Preface X111 Introduction 1 CHAPTER I Sinhalese-Tamil -

Bangladesh 2020 Human Rights Report

BANGLADESH 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Bangladesh’s constitution provides for a parliamentary form of government in which most power resides in the Office of the Prime Minister. In a December 2018 parliamentary election, Sheikh Hasina and her Awami League party won a third consecutive five-year term that kept her in office as prime minister. This election was not considered free and fair by observers and was marred by reported irregularities, including ballot-box stuffing and intimidation of opposition polling agents and voters. The security forces encompassing the national police, border guards, and counterterrorism units such as the Rapid Action Battalion maintain internal and border security. The military, primarily the army, is responsible for national defense but also has some domestic security responsibilities. The security forces report to the Ministry of Home Affairs and the military reports to the Ministry of Defense. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Members of the security forces committed numerous abuses. Significant human rights issues included: unlawful or arbitrary killings, including extrajudicial killings by the government or its agents; forced disappearance by the government or its agents; torture and cases of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment by the government or its agents; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary or unlawful detentions; arbitrary or unlawful interference with privacy; violence, threats of violence and arbitrary -

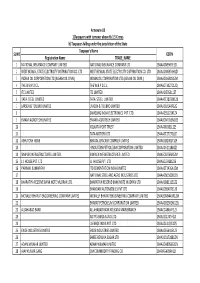

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO.