Company Neutral Revenue Support Scheme (CNRS)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Railfreight in Colour for the Modeller and Historian Free

FREE RAILFREIGHT IN COLOUR FOR THE MODELLER AND HISTORIAN PDF David Cable | 96 pages | 02 May 2009 | Ian Allan Publishing | 9780711033641 | English | Surrey, United Kingdom PDF Br Ac Electric Locomotives In Colour Download Book – Best File Book The book also includes a historical examination of the development of electric locomotives, allied to hundreds of color illustrations with detailed captions. An outstanding collection of photographs revealing the life and times of BR-liveried locomotives and rolling stock at a when they could be seen Railfreight in Colour for the Modeller and Historian across the network. The AL6 or Class 86 fleet of ac locomotives represents the BRB ' s second generation of main - line electric traction. After introduction of the various new business sectorsInterCity colours appeared in various guiseswith the ' Swallow ' livery being applied from Also in Cab superstructure — Light grey colour aluminium paint considered initially. The crest originally proposed was like that used on the AC electric locomotives then being deliveredbut whether of cast aluminium or a transfer is not quite International Railway Congress at Munich 60 years of age and over should be given the B. Multiple - aspect colour - light signalling has option of retiring on an adequate pension to Consideration had been given to AC Locomotive Group reports activity on various fronts in connection with its comprehensive collection of ac electric locos. Some of the production modelshoweverwill be 25 kV ac electric trains designed to work on BR ' s expanding electrified network. Headlight circuits for locomotives used in multiple - unit operation may be run through the end jumpers to a special selector switch remote Under the tower's jurisdiction are 4 color -light signals and subsidiary signals for Railfreight in Colour for the Modeller and Historian movements. -

The Role for Rail in Port-Based Container Freight Flows in Britain

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by WestminsterResearch The role for rail in port-based container freight flows in Britain ALLAN WOODBURN Bionote Dr Allan Woodburn is a Senior Lecturer in the Transport Studies Group at the University of Westminster, London, NW1 5LS. He specialises in freight transport research and teaching, mainly related to operations, planning and policy and with a particular interest in rail freight. 1 The role for rail in port-based container freight flows in Britain ALLAN WOODBURN Email: [email protected] Tel: +44 20 7911 5000 Fax: +44 20 7911 5057 Abstract As supply chains become increasingly global and companies seek greater efficiencies, the importance of good, reliable land-based transport linkages to/from ports increases. This poses particular problems for the UK, with its high dependency on imported goods and congested ports and inland routes. It is conservatively estimated that container volumes through British ports will double over the next 20 years, adding to the existing problems. This paper investigates the potential for rail to become better integrated into port-based container flows, so as to increase its share of this market and contribute to a more sustainable mode split. The paper identifies the trends in container traffic through UK ports, establishes the role of rail within this market, and assesses the opportunities and threats facing rail in the future. The analysis combines published statistics and other information relating to container traffic and original research on the nature of the rail freight market, examining recent trends and future prospects. -

The Commercial & Technical Evolution of the Ferry

THE COMMERCIAL & TECHNICAL EVOLUTION OF THE FERRY INDUSTRY 1948-1987 By William (Bill) Moses M.B.E. A thesis presented to the University of Greenwich in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2010 DECLARATION “I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised another’s work”. ……………………………………………. William Trevor Moses Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Sarah Palmer Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Alastair Couper Date:……………………………. ii Acknowledgements There are a number of individuals that I am indebted to for their support and encouragement, but before mentioning some by name I would like to acknowledge and indeed dedicate this thesis to my late Mother and Father. Coming from a seafaring tradition it was perhaps no wonder that I would follow but not without hardship on the part of my parents as they struggled to raise the necessary funds for my books and officer cadet uniform. Their confidence and encouragement has since allowed me to achieve a great deal and I am only saddened by the fact that they are not here to share this latest and arguably most prestigious attainment. It is also appropriate to mention the ferry industry, made up on an intrepid band of individuals that I have been proud and privileged to work alongside for as many decades as covered by this thesis. -

Connections 03 05

Vol. 4 • no.1 April 2005 The story of Jesus has been the single greatest influence in shaping Europe’s past. Why should it not also be the single greatest influence in shaping Europe’s future? This book is about the role in shaping Europe’s future together! “I really believe this book is desperately needed in Europe” George Verwer, founder Operation Mobilisation For information and to order: www.initialmedia.com [email protected] O VOL. 4 • N .1 EDITORIAL From the Heart and Mind of the Editor The high calling upon the Mission Commission (MC) is to focus review three very diverse and cur- rent books on Christians in China. on the extension of the Kingdom of God in Christ. We want to Some of our readers may not agree be known as a missional structure, intent on establishing with everything Sam writes, but we Kingdom outposts around the world. We want to respond to the will all be stirred to think seriously about God’s work in that “center of cutting edge concerns of the missional people of God—the the human universe”. The other church on the move in all of its forms; serving within cultures books are almost a polar opposite as Cathy Ross introduces us to the William Taylor is the Executive and cross-culturally; near and far; home and abroad; Director of the WEA Mission very adventuresome and delightful Commission. Born in Latin evangelizing and discipling; proclaiming and serving; Mma Precious Ramotswe of America, he and his wife, expanding and missiologizing; weeping and sowing. -

The Regional Impact of the Channel Tunnel Throughout the Community

-©fine Channel Tunnel s throughpdrth^Çpmmunity European Commission European Union Regional Policy and Cohesion Regional development studies The regional impact of the Channel Tunnel throughout the Community European Commission Already published in the series Regional development studies 01 — Demographic evolution in European regions (Demeter 2015) 02 — Socioeconomic situation and development of the regions in the neighbouring countries of the Community in Central and Eastern Europe 03 — Les politiques régionales dans l'opinion publique 04 — Urbanization and the functions of cities in the European Community 05 — The economic and social impact of reductions in defence spending and military forces on the regions of the Community 06 — New location factors for mobile investment in Europe 07 — Trade and foreign investment in the Community regions: the impact of economic reform in Central and Eastern Europe 08 — Estudio prospectivo de las regiones atlánticas — Europa 2000 Study of prospects in the Atlantic regions — Europe 2000 Étude prospective des régions atlantiques — Europe 2000 09 — Financial engineering techniques applying to regions eligible under Objectives 1, 2 and 5b 10 — Interregional and cross-border cooperation in Europe 11 — Estudio prospectivo de las regiones del Mediterráneo Oeste Évolution prospective des régions de la Méditerranée - Ouest Evoluzione delle prospettive delle regioni del Mediterraneo occidentale 12 — Valeur ajoutée et ingénierie du développement local 13 — The Nordic countries — what impact on planning and development -

A Study of the Community Benefit of a Fixed Channel

A J Jl'if: COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES ] 1 J ] 1 STUDY OF THE COMMUNITY BENEFIT J i OF A FIXED CHANNEL CROSSING i i j f..»y APPENDICES M J 1 DECEMBER 1979 ,,^~r r,r*"ï i?T ^^.t . • CDAT 8139 C COOPERS & LYBRAND ASSOCIATES LIMITED MANAGEMENT AND ECONOMIC CONSULTANTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 'A. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN CROSS-CHANNEL TRAFFIC Aol Developments in Transport Services A.1.1 Shipping : Passengers A.1.2 Shipping : Freight A.1.3 Shipping : Capacity and Technical Developments A.1.4 Hovercraft and Jetfoil Services o A.1.5 Air A.1.6 Surface Connections A.2 Routes Chosen by UK Résidents in 1977 A.2.1 Introduction A.2.2 Independent, Non-Car Leisure Travellers A.2.3 Leisure Car Travellers i] A.2.4 Package Travellers A.2.5 Business Travellers •Or- :\ A.3 Developments in Freight Traffic • •• * 0 •'•-•; A.3.1 Récent Developments in Unitised Cross-Channel Traffic A.3.2 Road Ro-Ro Traffic Growth A.3.3 Conclusions . J B. MODELS OF ROUTE CHOICE B.l Introduction B.l.l Manipulation of Route Data B.1.2 Network Processing B.l.3 The Choice of Zoning System B.2 The Route Choice Model for Car Travellers B.2.1 The Network B.2.2 The Model Structure B.2.3 The Impédance Function B.2.4 The Choice Between French and Belgian Straits B.2.5 The Choice Between Calais and Boulogne B.2.6 The Choice Between Ship and Hovercraft 7»? ï'ï B.3 The Route Choice Model for Non-Car Travellers B.3.1 The Network B.3.2 The Impédance Function for Independent Travellers B.3.3 The Impédance Function for Package Travellers B.4 The Route Choice Model for Freight B.5 The Evaluation of User Benefits B.5.1 Method B.5.2 Units C. -

Volume 16 Number 2

THE TRANSPORT ECONOMIST MAGAZINE OF THE TRANSPORT ECONOMISTS GROUP VOLUME 16 NUMBER 2 EDITOR: Stuart Cole, Polytechnic of North London Business School Contents Page RECENT MEETINGS The economics of regulation in the taxicab industry Ken Gwilliam (Leeds, November 1988) 1 The role of Hoverspeed in the cross-Channel market Robin Wilkins (London, November 1988) 3 BOOK REV IEWS The Manchester Tramways (Ian Yearsley & Philip Groves) 15 1 Geoffrey Searle: An appreciation 17 RECENT MEETINGS TEG NEWS THE ECONOMICS OF REGULATION IN THE TAXICAB INDUSTRY Notice of Annual General Meeting 18 Ken Gwilliam, Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds (Leeds, November 9 1988) Membership News 19 Local authorities have had powers to regulate entry, fares Programme of Meetings 20 and conditions of operation for taxis ever since the Town Police Clauses Act of 1847. and most exercise these powers. The 1985 Committee 21 Act liberalised entry to the industry. but allowed authorities to refuse licenses if it could be demonstrated that there was no Copy Dates 22 'significant unmet demand', Thus there has been a growing industry in studies of taxi demand, of which the Institute at Leeds has undertaken a SUbstantial number. Evidence from cases fought through the Crown Courts so far suggested that it was very difficult to define what is meant by significant unmet demand, with consequential inconsistencies in decisions. For instance in Stockton the growth in the number of hire cars was accepted as evidence of unmet demand, whereas in similar circumstances elsewhere that argument has failed. Similarly the degree to which a lack of taxis at peak times or in out-of-cntre locations has been accepted as evidence has varied. -

Gateway Cities Technology Plan for Goods Movement

Final Report Gateway Cities Technology Plan for Goods Movement Task 1: Background Research prepared for Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 555 12th Street, Suite 1600 Oakland, CA 94607 date March 2012 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Study Overview .......................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 ITS Integration Plan .................................................................................... 1-5 1.3 ITS Working Group .................................................................................... 1-6 1.4 Project Tasks and Phasing ......................................................................... 1-8 1.5 Overview of Task 1 Report ...................................................................... 1-11 2.0 ITS Data and Transportation Management ................................................... 2-1 Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 2-1 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 2-5 2.2 ITS Data and Transportation Management Inventory and Systems ......................................................................................................... 2-9 2.3 Key ITS Traffic Data Summary .............................................................. -

Latham&Watki Nsllp

555 Eleventh Street, N.W., Suite 1000 Washington, D.C. 20004-1304 Tel: +1.202.637.2200 Fax: +1.202.637.2201 www.lw.com FIRM / AFFILIATE OFFICES LATHAM&WATKI N SLLP Barcelona New Jersey Brussels New York Chicago Northern Virginia Dubai Orange County Frankfurt Paris August 26, 2008 Hamburg Rome Hong Kong San Diego London San Francisco Los Angeles Shanghai Ms. Marlene H. Dortch Madrid Silicon Valley Secretary Milan Singapore Federal Communications Commission Moscow Tokyo Munich Washington, D.C. 445 12th Street, SW Washington, DC 20554 Re: Applications for Consent to Transfer Control of Stratos Global Corporation and Its Subsidiaries from an Irrevocable Trust to Inmarsat plc, IB Docket No. 08-143, DA 08-1659 Dear Ms. Dortch: Inmarsat plc respectfully submits this corrected copy of its Opposition, filed August 25, 2008. As filed, the first page after the Summary inadvertently contained a “draft” header that was an artifact from before the document was finalized for filing. The attached corrected Opposition removes that stray header, but is otherwise identical to the document filed on August 25, 2008. Please contact the undersigned if you have any questions. Sincerely yours, /s/ John P. Janka Jeffrey A. Marks Counsel for Inmarsat plc Attachment CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I, Jeffrey A. Marks, hereby certify that on this 26th day of August 2008, I caused to be served a true copy of the foregoing by first class mail, postage pre-paid (or as otherwise indicated) upon the following: John F. Copes* Gail Cohen* Policy Division, International Bureau Wireline Competition Bureau Federal Communications Commission Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street, S.W. -

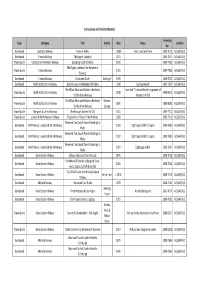

Publicity Material List

Early Guides and Publicity Material Inventory Type Company Title Author Date Notes Location No. Guidebook Cambrian Railway Tours in Wales c 1900 Front cover not there 2000-7019 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook Furness Railway The English Lakeland 1911 2000-7027 ALS5/49/A/1 Travel Guide Cambrian & Mid-Wales Railway Gossiping Guide to Wales 1870 1999-7701 ALS5/49/A/1 The English Lakeland: the Paradise of Travel Guide Furness Railway 1916 1999-7700 ALS5/49/A/1 Tourists Guidebook Furness Railway Illustrated Guide Golding, F 1905 2000-7032 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook North Staffordshire Railway Waterhouses and the Manifold Valley 1906 Card bookmark 2001-7197 ALS5/49/A/1 The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Inscribed "To Aman Mosley"; signature of Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1908 1999-8072 ALS5/29/A/1 Staffordshire Railway chairman of NSR The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Moores, Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1891 1999-8083 ALS5/49/A/1 Staffordshire Railway George Travel Guide Maryport & Carlisle Railway The Borough Guides: No 522 1911 1999-7712 ALS5/29/A/1 Travel Guide London & North Western Railway Programme of Tours in North Wales 1883 1999-7711 ALS5/29/A/1 Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7680 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7681 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, -

Railnews 2009 Directory

Railnews 2009 Directory 1.Train Operators Full listing of all UK passenger & freight operating companies in the UK 2. Recruitment & Training Companies & government-run organisations focused on training and recruitment within the UK rail industry 3. Industry Stakeholders Government & independent organisations including Network Rail and the BTP 4. Industry Suppliers UK and International companies supplying, manufacturing and serving the UK industry 5. Industry Representatives Rail and transport unions Railnews Ltd, 180-186 Kings Cross Road, Kings Cross Business Centre, London, WC1X 9DE | 020 7689 1610 | www.railnews.co.uk | [email protected] Train Operators Train Operators ARRIVA PLC Fax: 01603 214 517 Managing Director UK Trains: Bob Holland Email: [email protected] EAST MIDLAND TRAINS (Stagecoach Group) Telephone: 0191 520 4000 Website: www.c2c-online.co.uk Managing Director: Tim Shoveller Email: [email protected] Postal Address: c2c Rail Ltd, 207 Old Street, London, EC1V 9NR Telephone: 08457 125 678 Website: www.arriva.co.uk Email: [email protected] Postal Address: Admiral Way, Doxford International Business Park, CHILTERN RAILWAYS (DB Regio/Laing Rail) Website: www.eastmidlandstrains.co.uk Sunderland, SR3 3XP Chairman: Adrian Shooter Postal Address: East Midlands Trains, 1 Prospect Place, Millennium Franchises: Arrive Trains Wales; CrossCountry. Telephone: 08456 005 165 Way, Pride Park, Derby, DE24 8HG Fax: 01296 332126 ARRIVA TRAINS WALES/TRENAU ARRIVA CYMRU Website: www.chilternrailways.co.uk EUROSTAR Managing Director: Tim Bell Postal Address: The Chiltern Railway Company Ltd, 2nd floor, Eurostar (UK) Ltd is part of Eurostar Group. the UK company is owned Telephone: 0845 6061660 Western House, 14 Rickfords Hill, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, HP20 by London and Continental Railways and managed by Inter Capital Fax: 02920 645349 2RX and Regional Rail Ltd, a consortium of National Express Group, Email: [email protected] Belgian Railways, French Railways and British Airways. -

Competition Act 1998

Competition Act 1998 Decision of the Office of Rail Regulation* English Welsh and Scottish Railway Limited Relating to a finding by the Office of Rail Regulation (ORR) of an infringement of the prohibition imposed by section 18 of the Competition Act 1998 (the Act) and Article 82 of the EC Treaty in respect of conduct by English Welsh and Scottish Railway Limited. Introduction 1. This decision relates to conduct by English Welsh and Scottish Railway Limited (EWS) in the carriage of coal by rail in Great Britain. 2. The case results from two complaints. 3. On 1 February 2001 Enron Coal Services Limited (ECSL)1 submitted a complaint to the Director of Fair Trading2. Jointly with ECSL, Freightliner Limited (Freightliner) also, within the same complaint, alleged an infringement of the Chapter II prohibition in respect of a locomotive supply agreement between EWS and General Motors Corporation of the United States (General Motors). Together these are referred to as the Complaint. The Complaint alleges: “[…] that English, Welsh and Scottish Railways Limited (‘EWS’), the dominant supplier of rail freight services in England, Wales and Scotland, has systematically and persistently acted to foreclose, deter or limit Enron Coal Services Limited’s (‘ECSL’) participation in the market for the supply of coal to UK industrial users, particularly in the power sector, to the serious detriment of competition in that market. The complaint concerns abusive conduct on the part of EWS as follows. • Discriminatory pricing as between purchasers of coal rail freight services so as to disadvantage ECSL. *Certain information has been excluded from this document in order to comply with the provisions of section 56 of the Competition Act 1998 (confidentiality and disclosure of information) and the general restrictions on disclosure contained at Part 9 of the Enterprise Act 2002.