Latham&Watki Nsllp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Commercial & Technical Evolution of the Ferry

THE COMMERCIAL & TECHNICAL EVOLUTION OF THE FERRY INDUSTRY 1948-1987 By William (Bill) Moses M.B.E. A thesis presented to the University of Greenwich in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2010 DECLARATION “I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised another’s work”. ……………………………………………. William Trevor Moses Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Sarah Palmer Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Alastair Couper Date:……………………………. ii Acknowledgements There are a number of individuals that I am indebted to for their support and encouragement, but before mentioning some by name I would like to acknowledge and indeed dedicate this thesis to my late Mother and Father. Coming from a seafaring tradition it was perhaps no wonder that I would follow but not without hardship on the part of my parents as they struggled to raise the necessary funds for my books and officer cadet uniform. Their confidence and encouragement has since allowed me to achieve a great deal and I am only saddened by the fact that they are not here to share this latest and arguably most prestigious attainment. It is also appropriate to mention the ferry industry, made up on an intrepid band of individuals that I have been proud and privileged to work alongside for as many decades as covered by this thesis. -

Connections 03 05

Vol. 4 • no.1 April 2005 The story of Jesus has been the single greatest influence in shaping Europe’s past. Why should it not also be the single greatest influence in shaping Europe’s future? This book is about the role in shaping Europe’s future together! “I really believe this book is desperately needed in Europe” George Verwer, founder Operation Mobilisation For information and to order: www.initialmedia.com [email protected] O VOL. 4 • N .1 EDITORIAL From the Heart and Mind of the Editor The high calling upon the Mission Commission (MC) is to focus review three very diverse and cur- rent books on Christians in China. on the extension of the Kingdom of God in Christ. We want to Some of our readers may not agree be known as a missional structure, intent on establishing with everything Sam writes, but we Kingdom outposts around the world. We want to respond to the will all be stirred to think seriously about God’s work in that “center of cutting edge concerns of the missional people of God—the the human universe”. The other church on the move in all of its forms; serving within cultures books are almost a polar opposite as Cathy Ross introduces us to the William Taylor is the Executive and cross-culturally; near and far; home and abroad; Director of the WEA Mission very adventuresome and delightful Commission. Born in Latin evangelizing and discipling; proclaiming and serving; Mma Precious Ramotswe of America, he and his wife, expanding and missiologizing; weeping and sowing. -

The Regional Impact of the Channel Tunnel Throughout the Community

-©fine Channel Tunnel s throughpdrth^Çpmmunity European Commission European Union Regional Policy and Cohesion Regional development studies The regional impact of the Channel Tunnel throughout the Community European Commission Already published in the series Regional development studies 01 — Demographic evolution in European regions (Demeter 2015) 02 — Socioeconomic situation and development of the regions in the neighbouring countries of the Community in Central and Eastern Europe 03 — Les politiques régionales dans l'opinion publique 04 — Urbanization and the functions of cities in the European Community 05 — The economic and social impact of reductions in defence spending and military forces on the regions of the Community 06 — New location factors for mobile investment in Europe 07 — Trade and foreign investment in the Community regions: the impact of economic reform in Central and Eastern Europe 08 — Estudio prospectivo de las regiones atlánticas — Europa 2000 Study of prospects in the Atlantic regions — Europe 2000 Étude prospective des régions atlantiques — Europe 2000 09 — Financial engineering techniques applying to regions eligible under Objectives 1, 2 and 5b 10 — Interregional and cross-border cooperation in Europe 11 — Estudio prospectivo de las regiones del Mediterráneo Oeste Évolution prospective des régions de la Méditerranée - Ouest Evoluzione delle prospettive delle regioni del Mediterraneo occidentale 12 — Valeur ajoutée et ingénierie du développement local 13 — The Nordic countries — what impact on planning and development -

A Study of the Community Benefit of a Fixed Channel

A J Jl'if: COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES ] 1 J ] 1 STUDY OF THE COMMUNITY BENEFIT J i OF A FIXED CHANNEL CROSSING i i j f..»y APPENDICES M J 1 DECEMBER 1979 ,,^~r r,r*"ï i?T ^^.t . • CDAT 8139 C COOPERS & LYBRAND ASSOCIATES LIMITED MANAGEMENT AND ECONOMIC CONSULTANTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 'A. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN CROSS-CHANNEL TRAFFIC Aol Developments in Transport Services A.1.1 Shipping : Passengers A.1.2 Shipping : Freight A.1.3 Shipping : Capacity and Technical Developments A.1.4 Hovercraft and Jetfoil Services o A.1.5 Air A.1.6 Surface Connections A.2 Routes Chosen by UK Résidents in 1977 A.2.1 Introduction A.2.2 Independent, Non-Car Leisure Travellers A.2.3 Leisure Car Travellers i] A.2.4 Package Travellers A.2.5 Business Travellers •Or- :\ A.3 Developments in Freight Traffic • •• * 0 •'•-•; A.3.1 Récent Developments in Unitised Cross-Channel Traffic A.3.2 Road Ro-Ro Traffic Growth A.3.3 Conclusions . J B. MODELS OF ROUTE CHOICE B.l Introduction B.l.l Manipulation of Route Data B.1.2 Network Processing B.l.3 The Choice of Zoning System B.2 The Route Choice Model for Car Travellers B.2.1 The Network B.2.2 The Model Structure B.2.3 The Impédance Function B.2.4 The Choice Between French and Belgian Straits B.2.5 The Choice Between Calais and Boulogne B.2.6 The Choice Between Ship and Hovercraft 7»? ï'ï B.3 The Route Choice Model for Non-Car Travellers B.3.1 The Network B.3.2 The Impédance Function for Independent Travellers B.3.3 The Impédance Function for Package Travellers B.4 The Route Choice Model for Freight B.5 The Evaluation of User Benefits B.5.1 Method B.5.2 Units C. -

Volume 16 Number 2

THE TRANSPORT ECONOMIST MAGAZINE OF THE TRANSPORT ECONOMISTS GROUP VOLUME 16 NUMBER 2 EDITOR: Stuart Cole, Polytechnic of North London Business School Contents Page RECENT MEETINGS The economics of regulation in the taxicab industry Ken Gwilliam (Leeds, November 1988) 1 The role of Hoverspeed in the cross-Channel market Robin Wilkins (London, November 1988) 3 BOOK REV IEWS The Manchester Tramways (Ian Yearsley & Philip Groves) 15 1 Geoffrey Searle: An appreciation 17 RECENT MEETINGS TEG NEWS THE ECONOMICS OF REGULATION IN THE TAXICAB INDUSTRY Notice of Annual General Meeting 18 Ken Gwilliam, Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds (Leeds, November 9 1988) Membership News 19 Local authorities have had powers to regulate entry, fares Programme of Meetings 20 and conditions of operation for taxis ever since the Town Police Clauses Act of 1847. and most exercise these powers. The 1985 Committee 21 Act liberalised entry to the industry. but allowed authorities to refuse licenses if it could be demonstrated that there was no Copy Dates 22 'significant unmet demand', Thus there has been a growing industry in studies of taxi demand, of which the Institute at Leeds has undertaken a SUbstantial number. Evidence from cases fought through the Crown Courts so far suggested that it was very difficult to define what is meant by significant unmet demand, with consequential inconsistencies in decisions. For instance in Stockton the growth in the number of hire cars was accepted as evidence of unmet demand, whereas in similar circumstances elsewhere that argument has failed. Similarly the degree to which a lack of taxis at peak times or in out-of-cntre locations has been accepted as evidence has varied. -

Torm Shipping Chooses VSAT for Entire Fleet

December 2008 Torm Shipping chooses IN THIS ISSUE VSAT for entire fleet satcoms Following an approximately six-month long trial aboard the Torm Vita, GlobeRydex, Rydex version 8, released - 5 Torm Shipping is to install SingTel’s newly launched VSAT system across its Why we moved from VSAT to FleetBroadband - 100-strong fleet, as Singtel looks to expand its market base Varun Shipping - 8 High-speed, small antenna - orm Shipping has installed on each vessel as SingTel's GMVSAT business productivity by agreed a contract to part of the service, for ship- core infrastructure is man- enabling its ships to mini-VSAT at Vadero Ship TTimplement to-ship and ship-to-shore aged over its ConnectPlus become seamless exten- Management - 10 SingTel's Global Maritime voice communications. Internet Protocol Virtual sions of the shore-based Satellite repositioning for global Fleet- Very Small Aperture Ter- Claus Usen Jensen, Private Network (IP VPN), office." minal (GMVSAT) service Torm Shipping's executive which will provide Torm "It will also improve Broadband to cause service outages - 10 aboard its fleet of 100 vice president, technical with an additional level of crew welfare by allowing ships, which will provide seafarers to undertake always-on broadband con- online distance training software nectivity for the Danish and stay in touch with shipping group on a loved ones while at sea." Canada’s largest dry-bulk worldwide basis. "This multi-million dol- company to implement IMOS The deal follows a trial lar contract demonstrates software system - 16 period that began in the Torm Shipping's confi- summer of 2008, which dence in SingTel to deliver Shipdex - predicting the costs of also marked the first cus- world-class ICT solutions. -

Gateway Cities Technology Plan for Goods Movement

Final Report Gateway Cities Technology Plan for Goods Movement Task 1: Background Research prepared for Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 555 12th Street, Suite 1600 Oakland, CA 94607 date March 2012 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Study Overview .......................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 ITS Integration Plan .................................................................................... 1-5 1.3 ITS Working Group .................................................................................... 1-6 1.4 Project Tasks and Phasing ......................................................................... 1-8 1.5 Overview of Task 1 Report ...................................................................... 1-11 2.0 ITS Data and Transportation Management ................................................... 2-1 Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 2-1 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 2-5 2.2 ITS Data and Transportation Management Inventory and Systems ......................................................................................................... 2-9 2.3 Key ITS Traffic Data Summary .............................................................. -

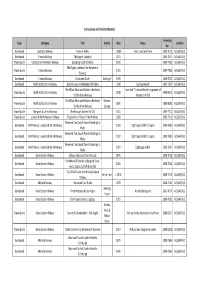

Publicity Material List

Early Guides and Publicity Material Inventory Type Company Title Author Date Notes Location No. Guidebook Cambrian Railway Tours in Wales c 1900 Front cover not there 2000-7019 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook Furness Railway The English Lakeland 1911 2000-7027 ALS5/49/A/1 Travel Guide Cambrian & Mid-Wales Railway Gossiping Guide to Wales 1870 1999-7701 ALS5/49/A/1 The English Lakeland: the Paradise of Travel Guide Furness Railway 1916 1999-7700 ALS5/49/A/1 Tourists Guidebook Furness Railway Illustrated Guide Golding, F 1905 2000-7032 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook North Staffordshire Railway Waterhouses and the Manifold Valley 1906 Card bookmark 2001-7197 ALS5/49/A/1 The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Inscribed "To Aman Mosley"; signature of Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1908 1999-8072 ALS5/29/A/1 Staffordshire Railway chairman of NSR The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Moores, Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1891 1999-8083 ALS5/49/A/1 Staffordshire Railway George Travel Guide Maryport & Carlisle Railway The Borough Guides: No 522 1911 1999-7712 ALS5/29/A/1 Travel Guide London & North Western Railway Programme of Tours in North Wales 1883 1999-7711 ALS5/29/A/1 Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7680 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7681 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, -

Addvalue Establishes Its First Tier 1 Distributor for Its New Skipper™ 150 Fleetbroadband Maritime Terminals

NEWS RELEASE ADDVALUE TECHNOLOGIES LTD Company Registration Number: 199603037H ADDVALUE ESTABLISHES ITS FIRST TIER 1 DISTRIBUTOR FOR ITS NEW SKIPPER™ 150 FLEETBROADBAND MARITIME TERMINALS Singapore, June 30, 2009 – Addvalue Technologies Ltd (“Addvalue”) announced today that its wholly-owned subsidiary, Addvalue Communications Pte Ltd, has entered into a distribution relationship with Vizada Americas (“Vizada”) making Vizada Addvalue’s first Tier 1 Distribution partner for Addvalue’s Skipper™ 150 FleetBroadband user terminal. “It is only fitting” said Addvalue’s Chairman and CEO, Dr. Colin Chan, “that Vizada is our first Tier 1 Distributor, considering the tremendous support that Vizada provided Addvalue when we introduced our first Inmarsat BGAN product, the Sabre 1, in early 2007. We are very excited to be working with Vizada again and we see Vizada’s long established experience as a world recognized leader in the maritime satellite communications industry as a significant advantage for Addvalue and our Skipper™ 150.” “Addvalue has provided reliable terminals to Vizada customers for many years and we are pleased to continue our relationship as a Tier 1 provider for the Skipper™ 150 FleetBroadband terminal which is an important part of our maritime solutions portfolio.” commented Bob Baker, President and Chief Operating Officer for Vizada Americas. The Skipper™ 150 FleetBroadband terminal will offer a voice connection at landline quality, simultaneous internet-capable IP data at up to 150kbps and a simple-to-use SMS messaging service. Operation of the Skipper™ 150 is easily accomplished Page 1 of 3 through the system’s built-in and user friendly web console, or through the 2” color LCD display on the system’s IP66 rated handset. -

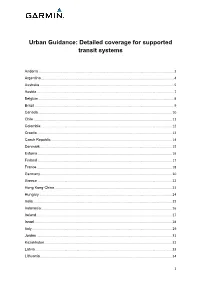

Urban Guidance: Detailed Coverage for Supported Transit Systems

Urban Guidance: Detailed coverage for supported transit systems Andorra .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Argentina ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Australia ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Austria .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Brazil ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ................................................................................................................................................ 10 Chile ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Colombia .............................................................................................................................................. 12 Croatia ................................................................................................................................................. -

Z-Family Technical Reference Manual

Z-Family Technical Reference Manual Ashtech 1170 Kifer Road Sunnyvale, CA USA 94086 Phone and Fax Numbers •Main • Voice: 408-524-1400 • Fax: 408-524-1500 • Sales • US: 800-922-2401 • International: 408-524-1670 • Fax: 408-524-1500 •Europe • Voice: 44-993-883-533 • Fax: 44-993-883-977 • Support • US: 800-229-2400 • International: 408-524-1680 • Fax: 408-524-1500 •BBS • Direct: 408-524-1527 Internet • [email protected] • http://www.ashtech.com Copyright Notice Copyright © 1998 Magellan Corporation. All rights reserved. No part of this publication or the computer programs described in it may be repro- duced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission of Magellan. Your rights with regard to this publication and the computer programs are subject to the restrictions and limitations imposed by the cop- yright laws of the United States of America (“U.S.A.”) and/or the jurisdiction in which you are located. For information on translations and distribution outside the U.S.A., please contact Ashtech. NO PATENT OR COPYRIGHT LIABILITY IS ASSUMED WITH RESPECT TO THE USE OF INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN. WHILE REASONABLE PRECAUTIONS HAVE BEEN TAKEN IN THE PREPARATION OF THIS PUB- LICATION, ASHTECH ASSUMES NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR ERRORS OR OMISSIONS, NOR IS ANY LIABILITY ASSUMED FOR DAMAGES RESULT- ING FROM THE USE OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN. FUR- THER, THIS PUBLICATION AND FEATURES DESCRIBED HEREIN ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. Printed in the United States of America. © Copyright May, 1998 Magellan Corporation Part Number: 630203-01, Revision A ii Z-Family Technical Reference Manual Trademarks Z-Surveyor, Z-FX, Z-Sensor, Z-Eurocard, GPSTopo, and the Ashtech logo are registered trademarks of Magellan. -

The Evolution of British Railways 1909-2009

The Evolution of British Railways 1909-2009 Britain’s Railways and The Railway Study Association 1909-2009 previously published in 2009 as part of A Century of Change 2019 Introduction to Second Edition Mike Horne FCILT MIRO This book was originally published by the name of ‘A Century of Change’ to commemorate the centenary of the Railway Study Association (RSA) in 1909; the Association is now the Railway Study Forum of the Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport. Plenty has already been written about the railways of Britain. When the time came to celebrate the activities of the RSA, it occurred to this author that there was something missing. I felt that although it is self-evident that the railway today is very different to that of a century ago, the real point was that railways have been in a state of constant evolution, in part to respond to the changing conditions of the country and in part because of technological change. More importantly, this change will continue. Few people entering the in- dustry today can have much conception of what these changes will be, but change there will be: big changes too. What I wanted to highlight is the huge way the railway has altered, particularly in its technology and operational practices. This has happened, with great success, under diffi cult political and fi nancial conditions. Although the railway has lost much of its market share, the numbers of people carried today have recovered dramatically, and the fact this has been done on a much smaller system is an in- credible achievement that needs to be promoted.