Analysis of Miocene Primates: Kenyapithecus, Sivapithecus, and Proconsul by Amanda Day a SENIOR THESIS for the UNIVERSITY HONORS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Evolution: a Paleoanthropological Perspective - F.H

PHYSICAL (BIOLOGICAL) ANTHROPOLOGY - Human Evolution: A Paleoanthropological Perspective - F.H. Smith HUMAN EVOLUTION: A PALEOANTHROPOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE F.H. Smith Department of Anthropology, Loyola University Chicago, USA Keywords: Human evolution, Miocene apes, Sahelanthropus, australopithecines, Australopithecus afarensis, cladogenesis, robust australopithecines, early Homo, Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, Australopithecus africanus/Australopithecus garhi, mitochondrial DNA, homology, Neandertals, modern human origins, African Transitional Group. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Reconstructing Biological History: The Relationship of Humans and Apes 3. The Human Fossil Record: Basal Hominins 4. The Earliest Definite Hominins: The Australopithecines 5. Early Australopithecines as Primitive Humans 6. The Australopithecine Radiation 7. Origin and Evolution of the Genus Homo 8. Explaining Early Hominin Evolution: Controversy and the Documentation- Explanation Controversy 9. Early Homo erectus in East Africa and the Initial Radiation of Homo 10. After Homo erectus: The Middle Range of the Evolution of the Genus Homo 11. Neandertals and Late Archaics from Africa and Asia: The Hominin World before Modernity 12. The Origin of Modern Humans 13. Closing Perspective Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary UNESCO – EOLSS The basic course of human biological history is well represented by the existing fossil record, although there is considerable debate on the details of that history. This review details both what is firmly understood (first echelon issues) and what is contentious concerning humanSAMPLE evolution. Most of the coCHAPTERSntention actually concerns the details (second echelon issues) of human evolution rather than the fundamental issues. For example, both anatomical and molecular evidence on living (extant) hominoids (apes and humans) suggests the close relationship of African great apes and humans (hominins). That relationship is demonstrated by the existing hominoid fossil record, including that of early hominins. -

Unravelling the Positional Behaviour of Fossil Hominoids: Morphofunctional and Structural Analysis of the Primate Hindlimb

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Doctorado en Biodiversitat Facultad de Ciènces Tesis doctoral Unravelling the positional behaviour of fossil hominoids: Morphofunctional and structural analysis of the primate hindlimb Marta Pina Miguel 2016 Memoria presentada por Marta Pina Miguel para optar al grado de Doctor por la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, programa de doctorado en Biodiversitat del Departamento de Biologia Animal, de Biologia Vegetal i d’Ecologia (Facultad de Ciències). Este trabajo ha sido dirigido por el Dr. Salvador Moyà Solà (Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont) y el Dr. Sergio Almécija Martínez (The George Washington Univertisy). Director Co-director Dr. Salvador Moyà Solà Dr. Sergio Almécija Martínez A mis padres y hermana. Y a todas aquelas personas que un día decidieron perseguir un sueño Contents Acknowledgments [in Spanish] 13 Abstract 19 Resumen 21 Section I. Introduction 23 Hominoid positional behaviour The great apes of the Vallès-Penedès Basin: State-of-the-art Section II. Objectives 55 Section III. Material and Methods 59 Hindlimb fossil remains of the Vallès-Penedès hominoids Comparative sample Area of study: The Vallès-Penedès Basin Methodology: Generalities and principles Section IV. -

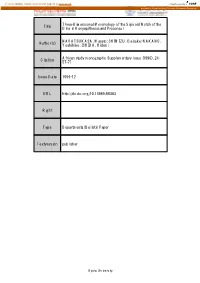

Title Three-Dimensional Morphology of the Sigmoid Notch of The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Three-Dimensional Morphology of the Sigmoid Notch of the Title Ulna in Kenyapithecus and Proconsul NAKATSUKASA, Masato; SHIMIZU, Daisuke; NAKANO, Author(s) Yoshihiko; ISHIDA, Hidemi African study monographs. Supplementary issue (1996), 24: Citation 57-71 Issue Date 1996-12 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/68383 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl. 24: 57-71, December 1996 57 THREE-DIMENSIONAL MORPHOLOGY OF THE SIGMOID NOTCH OF THE ULNA IN KENYAPITHECUS AND PROCONSUL Masato Nakatsukasa Daisuke Shimizu Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Faculty of Science, Kyoto University Yoshihiko Nakano Department of Biological Anthropology, Faculty of Human Sciences, Osaka University Hidemi Ishida Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Faculty of Science, Kyoto University ABSTRACT The three-dimensional (3-D) morphology of the sigmoid notch was examined in Kenyapithecus, Proconsul, and several living anthropoids by using an automatic 3-D digitizer. It was revealed that Kenyapithecus and Proconsul exhibit a very similar morphology of the dis tal region of the sigmoid notch; including the absence of a median keel and a downward sloped coronoid process. In addition, the proxilnal region of the sigmoid notch is curved more acutely relative to the distal region in Proconsul. This morphological complex is unique and not found in the examined living primates. The benefits of 3-D morphometries are discussed. Key Words: Kenyapithecus, Proconsul, sigmoid notch, three-dimensional morphometrics, ulna. INTRODUCTION Recently, automatic three-dimensional (3-0) digitizers have become more fre quently to be used for biometrics. -

Linnaean Taxonomic Classification Nomenclature All Biologists Use a Single Naming System That Essentially Follows the Practice O

Linnaean Taxonomic Classification Nomenclature All biologists use a single naming system that essentially follows the practice of Linnaeus. Taxa are always given Latin names (or Latinized ones). This is a label and not a definition. (Homo sapiens – wise man) The name of a species always consists of two words – the genus (generic) name followed by the species (specific) name. Grammatically, the genus is a noun and the species is adjective or another noun in opposition. The genus name is always capitalized and italicized. The species name is italicized only. If you used the genus name already you may use the first letter followed by a period. Homo sapiens, H. sapiens In the rare cases where a subgenus name is used it is capitalized, italicized and put in parentheses after the genus. Australopithecus (Paranthropus) robustus If a subspecies name is used it comes at the end and is italicized only. E.G. Homo sapiens sapiens Categories above the genus level are capitalized but not italicized. They generally have endings that show the level of classification. ini for tribe (Infraorder), oidea for superfamily, idae for family. Above the superfamily the only rule is that the name must be Latin or Latinized. The Latin names are often anglicized by dropping the ending and it is not normally capitalized. Hominidae – hominid. Technically the full name of the taxon should include the name of its inventor and the date but this is only done if the discussion is concerning the taxonomy of the name. Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758 Ideally, a taxon should have only one name, but some have been given more than one and there is a disagreement over which one has priority or which one is better. -

Glaciation (Oakley, 1950). Variations in the Proposed Beginning Dates

EVOLUTION OF THE HUMAN HAND AMD THE GREAT HAND-AXE TRADITION Grover S. Krantz The hand-axe is both the earliest and the longest persisting of standar- dized stone tools. They present a continuous history of one tool type from the first to the third interglacial periods, a span.of at least 200,000 years and perhaps as many as half a million. Equally remarkable is their geographical range which covers all of Africa, western Europe and southern Asia--fully half of-the then habitable Old Vorld. Aside from differences in the local stone that was utilized, hand-axes from this whole area are constructed on the same plan and show no clear regional typology. Other tool types occur with hand-axes: utilized flakes are found at all levels, and in the later half of the sequence there-are cleavers, ovates, trimmed flakes and spherical stone balls. Throughout the sequence, however, the basic design of the hand-axe continues with its intended formnapparently unchanged. We thus have a continuous record of man's attempts to produce a single type of 'implement over mst of his tool making history. (See Figure 1.) Recent discoveries of fossil man have made it increasingly evident that biological evolution of the human body was also in progress coincident with the development of ancient stone tool types. 'While the exact time of appearance of Homo siens is still in some dispute (see Stewart, 1950 and Oakley., 1957), it is no nowseriously maintained that the earliest tool makers necessarily approximated the modern or even the neanderthal morphologies. -

A Unique Middle Miocene European Hominoid and the Origins of the Great Ape and Human Clade Salvador Moya` -Sola` A,1, David M

A unique Middle Miocene European hominoid and the origins of the great ape and human clade Salvador Moya` -Sola` a,1, David M. Albab,c, Sergio Alme´ cijac, Isaac Casanovas-Vilarc, Meike Ko¨ hlera, Soledad De Esteban-Trivignoc, Josep M. Roblesc,d, Jordi Galindoc, and Josep Fortunyc aInstitucio´Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avanc¸ats at Institut Catala`de Paleontologia (ICP) and Unitat d’Antropologia Biolo`gica (Dipartimento de Biologia Animal, Biologia Vegetal, i Ecologia), Universitat Auto`noma de Barcelona, Edifici ICP, Campus de Bellaterra s/n, 08193 Cerdanyola del Valle`s, Barcelona, Spain; bDipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita`degli Studi di Firenze, Via G. La Pira 4, 50121 Florence, Italy; cInstitut Catala`de Paleontologia, Universitat Auto`noma de Barcelona, Edifici ICP, Campus de Bellaterra s/n, 08193 Cerdanyola del Valle`s, Barcelona, Spain; and dFOSSILIA Serveis Paleontolo`gics i Geolo`gics, S.L. c/ Jaume I nu´m 87, 1er 5a, 08470 Sant Celoni, Barcelona, Spain Edited by David Pilbeam, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and approved March 4, 2009 (received for review November 20, 2008) The great ape and human clade (Primates: Hominidae) currently sediments by the diggers and bulldozers. After 6 years of includes orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and humans. fieldwork, 150 fossiliferous localities have been sampled from the When, where, and from which taxon hominids evolved are among 300-m-thick local stratigraphic series of ACM, which spans an the most exciting questions yet to be resolved. Within the Afro- interval of 1 million years (Ϸ12.5–11.3 Ma, Late Aragonian, pithecidae, the Kenyapithecinae (Kenyapithecini ؉ Equatorini) Middle Miocene). -

8. Primate Evolution

8. Primate Evolution Jonathan M. G. Perry, Ph.D., The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Stephanie L. Canington, B.A., The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Learning Objectives • Understand the major trends in primate evolution from the origin of primates to the origin of our own species • Learn about primate adaptations and how they characterize major primate groups • Discuss the kinds of evidence that anthropologists use to find out how extinct primates are related to each other and to living primates • Recognize how the changing geography and climate of Earth have influenced where and when primates have thrived or gone extinct The first fifty million years of primate evolution was a series of adaptive radiations leading to the diversification of the earliest lemurs, monkeys, and apes. The primate story begins in the canopy and understory of conifer-dominated forests, with our small, furtive ancestors subsisting at night, beneath the notice of day-active dinosaurs. From the archaic plesiadapiforms (archaic primates) to the earliest groups of true primates (euprimates), the origin of our own order is characterized by the struggle for new food sources and microhabitats in the arboreal setting. Climate change forced major extinctions as the northern continents became increasingly dry, cold, and seasonal and as tropical rainforests gave way to deciduous forests, woodlands, and eventually grasslands. Lemurs, lorises, and tarsiers—once diverse groups containing many species—became rare, except for lemurs in Madagascar where there were no anthropoid competitors and perhaps few predators. Meanwhile, anthropoids (monkeys and apes) emerged in the Old World, then dispersed across parts of the northern hemisphere, Africa, and ultimately South America. -

List of Entries

Volume 1.qxd 9/13/2005 3:29 PM Page ix GGGGG LIST OF ENTRIES Aborigines Anthropic principle Apes, greater Aborigines Anthropocentrism Apes, lesser Acheulean culture Anthropology and business Apollonian Acropolis Anthropology and Aquatic ape hypothesis Action anthropology epistemology Aquinas, Thomas Adaptation, biological Anthropology and the Third Arboreal hypothesis Adaptation, cultural World Archaeology Aesthetic appreciation Anthropology of men Archaeology and gender Affirmative action Anthropology of religion studies Africa, socialist schools in Anthropology of women Archaeology, biblical African American thought Anthropology, careers in Archaeology, environmental African Americans Anthropology, characteristics of Archaeology, maritime African thinkers Anthropology, clinical Archaeology, medieval Aggression Anthropology, cultural Archaeology, salvage Ape aggression Anthropology, economic Architectural anthropology Agricultural revolution Anthropology, history of Arctic Agriculture, intensive Future of anthropology Ardrey, Robert Agriculture, origins of Anthropology, humanistic Argentina Agriculture, slash-and-burn Anthropology, philosophical Aristotle Alchemy Anthropology, practicing Arsuaga, J. L. Aleuts Anthropology, social Art, universals in ALFRED: The ALlele FREquency Anthropology and sociology Artificial intelligence Database Social anthropology Artificial intelligence Algonquians Anthropology, subdivisions of Asante Alienation Anthropology, theory in Assimilation Alienation Anthropology, Visual Atapuerca Altamira cave -

Chapter 18 Body Size and Intelligence in Hominoid Evolution

Chapter 18 ................................ ................................ Body Size and Intelligence in Hominoid ................................ ................................ chapter Evolution ................................ ................................ Carol Ward ................................ Department of Anthropology – Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences ................................ 107 Swallow Hall, University of Missouri ................................ Columbia, MO 65211 USA ................................ [email protected] ................................ Mark Flinn ................................ Department of Anthropology, 107 Swallow Hall, University of Missouri ................................ Columbia, MO 65211 USA ................................ [email protected] ................................ David Begun ................................ Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto ................................ Toronto, ON M5S 3G3, Canada ................................ [email protected] ................................ ................................ Word count: text (6526) XML Typescript c Cambridge University Press – Generated by TechBooks. Body Size and Intelligence in Hominoid Evolution Page 1218 of 1365 A-Head 1 Introduction ................................ ................................ 2 Great apes and humans are the largest brained primates. Aside from a few ................................ 3 extinct subfossil lemurs, they are also the largest in body mass. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Wrist and Ankle Morphology of Hominoids and Lorisids, with Implications for the Evolution of Hominoid Locomotion

Durham E-Theses A comparative analysis of the wrist and ankle morphology of hominoids and lorisids, with implications for the evolution of hominoid locomotion Read, Catriona S. How to cite: Read, Catriona S. (2001) A comparative analysis of the wrist and ankle morphology of hominoids and lorisids, with implications for the evolution of hominoid locomotion, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3775/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 A Comparative Analysis of the Wrist and Ankle Morphology of Hominoids and Lorisids, with Implications for the Evolution of Hominoid Locomotion A Dissertation presented by Catriona S. Read to The Graduate School For the degree of Master of Science m Biological Anthropology Department of Anthropology University of Durham September 2001 The co11yright of this thesis rests with the author. -

Fossil Primates

AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education Page 1 of 16 www.accessscience.com Fossil primates Contributed by: Eric Delson Publication year: 2014 Extinct members of the order of mammals to which humans belong. All current classifications divide the living primates into two major groups (suborders): the Strepsirhini or “lower” primates (lemurs, lorises, and bushbabies) and the Haplorhini or “higher” primates [tarsiers and anthropoids (New and Old World monkeys, greater and lesser apes, and humans)]. Some fossil groups (omomyiforms and adapiforms) can be placed with or near these two extant groupings; however, there is contention whether the Plesiadapiformes represent the earliest relatives of primates and are best placed within the order (as here) or outside it. See also: FOSSIL; MAMMALIA; PHYLOGENY; PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY; PRIMATES. Vast evidence suggests that the order Primates is a monophyletic group, that is, the primates have a common genetic origin. Although several peculiarities of the primate bauplan (body plan) appear to be inherited from an inferred common ancestor, it seems that the order as a whole is characterized by showing a variety of parallel adaptations in different groups to a predominantly arboreal lifestyle, including anatomical and behavioral complexes related to improved grasping and manipulative capacities, a variety of locomotor styles, and enlargement of the higher centers of the brain. Among the extant primates, the lower primates more closely resemble forms that evolved relatively early in the history of the order, whereas the higher primates represent a group that evolved more recently (Fig. 1). A classification of the primates, as accepted here, appears above. Early primates The earliest primates are placed in their own semiorder, Plesiadapiformes (as contrasted with the semiorder Euprimates for all living forms), because they have no direct evolutionary links with, and bear few adaptive resemblances to, any group of living primates. -

Australopiths Wading? Homo Diving?

Symposium: Water and Human Evolution, April 30th 1999, University Gent, Flanders, Belgium Proceedings Australopiths wading? Homo diving? http://allserv.rug.ac.be/~mvaneech/Symposium.html http://www.flash.net/~hydra9/marcaat.html Marc Verhaegen & Stephen Munro – 23 July 1999 Abstract Asian pongids (orangutans) and African hominids (gorillas, chimpanzees and humans) split 14-10 million years ago, possibly in the Middle East, or elsewhere in Eurasia, where the great ape fossils of 12-8 million years ago display pongid and/or hominid features. In any case, it is likely that the ancestors of the African apes, australopithecines and humans, lived on the Arabian-African continent 8-6 million years ago, when they split into gorillas and humans-chimpanzees. They could have frequently waded bipedally, like mangrove proboscis monkeys, in the mangrove forests between Eurasia and Africa, and partly fed on hard-shelled fruits and oysters like mangrove capuchin monkeys: thick enamel plus stone tool use is typically seen in capuchins, hominids and sea otters. The australopithecines might have entered the African inland along rivers and lakes. Their dentition suggests they ate mostly fruits, hard grass-like plants, and aquatic herbaceous vegetation (AHV). The fossil data indicates that the early australopithecines of 4-3 million years ago lived in waterside forests or woodlands; and their larger, robust relatives of 2-1 million years ago in generally more open milieus near marshes and reedbeds, where they could have waded bipedally. Some anthropologists believe the present-day African apes evolved from australopithecine-like ancestors, which would imply that knuckle-walking gorillas and chimpanzees evolved in parallel from wading- climbing ‘aquarborealists’.