Aa, Ee, Ea, Oo, Oi, Ou, Eu, Ai, Ei Ow, Oy, Ew, Ey, Uw, Aw, Ay U (When at the End of a Word) Ogh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

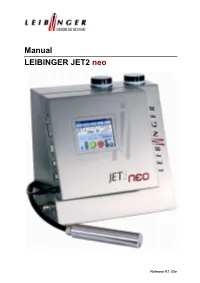

Manual LEIBINGER JET2 Neo

Manual LEIBINGER JET2 neo Release R1.00e Group 1 Table of contents Page 1 1.1 Table of contents 1.1 Table of contents ..........................................................................................................1 1.2 Group directory.............................................................................................................9 1.3 Publisher.....................................................................................................................10 1.4 Introduction.................................................................................................................12 1.5 Document information.................................................................................................13 1.6 Guarantee...................................................................................................................13 2. Safety ..............................................................................................................................14 2.1 Dangers......................................................................................................................14 2.2 Safety instructions and recommendations...................................................................14 2.3 Intended use...............................................................................................................16 2.4 Safety sticker ..............................................................................................................17 2.5 Operating staff ............................................................................................................18 -

The Origin of the Peculiarities of the Vietnamese Alphabet André-Georges Haudricourt

The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet André-Georges Haudricourt To cite this version: André-Georges Haudricourt. The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet. Mon-Khmer Studies, 2010, 39, pp.89-104. halshs-00918824v2 HAL Id: halshs-00918824 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00918824v2 Submitted on 17 Dec 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Published in Mon-Khmer Studies 39. 89–104 (2010). The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet by André-Georges Haudricourt Translated by Alexis Michaud, LACITO-CNRS, France Originally published as: L’origine des particularités de l’alphabet vietnamien, Dân Việt Nam 3:61-68, 1949. Translator’s foreword André-Georges Haudricourt’s contribution to Southeast Asian studies is internationally acknowledged, witness the Haudricourt Festschrift (Suriya, Thomas and Suwilai 1985). However, many of Haudricourt’s works are not yet available to the English-reading public. A volume of the most important papers by André-Georges Haudricourt, translated by an international team of specialists, is currently in preparation. Its aim is to share with the English- speaking academic community Haudricourt’s seminal publications, many of which address issues in Southeast Asian languages, linguistics and social anthropology. -

Daniel O'connell

Daniel O’Connell 708 Hoover St., Norman OK 73072 (405) 820-6218 – [email protected] EDUCATION ACCELERATED DUAL DEGREE PROGRAM: Completing Petroleum Engineering undergraduate Degree and an MBA concurrently Michael F. Price College of Business, University of Oklahoma Norman, OK Master of Business Administration; GPA: 4.0/4.0 May 2018 Training the Street; Two-Day Financial Modeling Seminar Mewbourne College of Earth and Energy, University of Oklahoma Norman, OK Bachelor of Science in Petroleum Engineering; GPA: 3.4/4.0 May 2018 EXPERIENCE May 2017- Gulfport Energy Oklahoma City, OK August 2017 Reservoir Engineering, (Internship) Forecasted oil, gas, and water production and revenues for all PDP wells within ARIES Quantified the effect of compression and spacing on already producing wells Created a water type-curve lookup table within ARIES, based on correlations found in Spotfire, to be used in water production forecasting for new wells drilled in the Utica January 2017- OU Center for Creation of Economic Wealth (CCEW) Norman, OK May 2017 Oklahoma Funding Accelerator Consulting Associate (Internship) Semester-long internship working closely with local Oklahoma City startup, SendARide, on business model generation, business plan creation, financial projections, and loan proposal preparation Researched and suggested top priority candidates for adoption of the SendARide app Explored healthcare regulations for possible limitations and opportunities for success May 2016- LINN Energy Agua Dulce, TX August 2016 Production Engineering, -

Influences on the Development of Early Modern English

Influences on the Development of Early Modern English Kyli Larson Wright This article covers the basic social, historical, and linguistic influences that have transformed the English language. Research first describes components of Early Modern English, then discusses how certain factors have altered the lexicon, phonology, and other components. Though there are many factors that have shaped English to what it is today, this article only discusses major factors in simple and straightforward terms. 72 Introduction The history of the English language is long and complicated. Our language has shifted, expanded, and has eventually transformed into the lingua franca of the modern world. During the Early Modern English period, from 1500 to 1700, countless factors influenced the development of English, transforming it into the language we recognize today. While the history of this language is complex, the purpose of this article is to determine and map out the major historical, social, and linguistic influences. Also, this article helps to explain the reasons for their influence through some examples and evidence of writings from the Early Modern period. Historical Factors One preliminary historical event that majorly influenced the development of the language was the establishment of the print- ing press. Created in 1476 by William Caxton at Westminster, London, the printing press revolutionized the current language form by creating a means for language maintenance, which helped English gravitate toward a general standard. Manuscripts could be reproduced quicker than ever before, and would be identical copies. Because of the printing press spelling variation would eventually decrease (it was fixed by 1650), especially in re- ligious and literary texts. -

The English Language

The English Language Version 5.0 Eala ðu lareow, tæce me sum ðing. [Aelfric, Grammar] Prof. Dr. Russell Block University of Applied Sciences - München Department 13 – General Studies Winter Semester 2008 © 2008 by Russell Block Um eine gute Note in der Klausur zu erzielen genügt es nicht, dieses Skript zu lesen. Sie müssen auch die “Show” sehen! Dieses Skript ist der Entwurf eines Buches: The English Language – A Guide for Inquisitive Students. Nur der Stoff, der in der Vorlesung behandelt wird, ist prüfungsrelevant. Unit 1: Language as a system ................................................8 1 Introduction ...................................... ...................8 2 A simple example of structure ..................... ......................8 Unit 2: The English sound system ...........................................10 3 Introduction..................................... ...................10 4 Standard dialects ................................ ....................10 5 The major differences between German and English . ......................10 5.1 The consonants ................................. ..............10 5.2 Overview of the English consonants . ..................10 5.3 Tense vs. lax .................................. ...............11 5.4 The final devoicing rule ....................... .................12 5.5 The “th”-sounds ................................ ..............12 5.6 The “sh”-sound .................................. ............. 12 5.7 The voiced sounds / Z/ and / dZ / ...................................12 5.8 The -

Ligature Modeling for Recognition of Characters Written in 3D Space Dae Hwan Kim, Jin Hyung Kim

Ligature Modeling for Recognition of Characters Written in 3D Space Dae Hwan Kim, Jin Hyung Kim To cite this version: Dae Hwan Kim, Jin Hyung Kim. Ligature Modeling for Recognition of Characters Written in 3D Space. Tenth International Workshop on Frontiers in Handwriting Recognition, Université de Rennes 1, Oct 2006, La Baule (France). inria-00105116 HAL Id: inria-00105116 https://hal.inria.fr/inria-00105116 Submitted on 10 Oct 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Ligature Modeling for Recognition of Characters Written in 3D Space Dae Hwan Kim Jin Hyung Kim Artificial Intelligence and Artificial Intelligence and Pattern Recognition Lab. Pattern Recognition Lab. KAIST, Daejeon, KAIST, Daejeon, South Korea South Korea [email protected] [email protected] Abstract defined shape of character while it showed high recognition performance. Moreover when a user writes In this work, we propose a 3D space handwriting multiple stroke character such as ‘4’, the user has to recognition system by combining 2D space handwriting write a new shape which is predefined in a uni-stroke models and 3D space ligature models based on that the and which he/she has never seen. -

A Corpus·Based Investigation of Xhosa English In

A CORPUS·BASED INVESTIGATION OF XHOSA ENGLISH IN THE CLASSROOM SETTING A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS of RHODES UNIVERSITY by CANDICE LEE PLATT January 2004 Supervisor: Professor V.A de K1erk ABSTRACT This study is an investigation of Xhosa English as used by teachers in the Grahamstown area of the Eastern Cape. The aims of the study were firstly, to compile a 20 000 word mini-corpus of the spoken English of Xhosa mother tongue teachers in Grahamstown, and to use this data to describe the characteristics of Xhosa English used in the classroom context; and secondly, to assess the usefulness of a corpus-based approach to a study of this nature. The English of five Xhosa mother-tongue teachers was investigated. These teachers were recorded while teaching in English and the data was then transcribed for analysis. The data was analysed using Wordsmith Tools to investigate patterns in the teachers' language. Grammatical, lexical and discourse patterns were explored based on the findings of other researchers' investigations of Black South African English and Xhosa English. In general, many of the patterns reported in the literature were found in the data, but to a lesser extent than reported in literature which gave quantitative information. Some features not described elsewhere were also found . The corpus-based approach was found to be useful within the limits of pattern matching. 1I TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1.1 CORPORA 1 1.2 BLACK SOUTH -

Writing & Language Development Center Phonetic Alphabet for English Language Learners Pin, Play, Top, Pretty, Poppy, Possibl

Writing & Language Development Center Phonetic Alphabet f o r English Language Learners A—The Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is a system of phonetic symbols developed by linguists to represent P each of the wide variety of sounds (phones or phonemes) used in spoken human language. This includes both vowel and consonant sounds. The IPA is used to signal the pronunciation of words. Each symbol is treated separately, with examples (like those used in the dictionary) so you can pronounce the word in American English. Single consonant sounds Symbol Sound Example p p in “pen” pin, play, top, pretty, poppy, possible, pepper, pour t t in “taxi” tell, time, toy, tempted, tent, tender, bent, taste, to ɾ or ţ t in “bottle” butter, writer, rider, pretty, matter, city, pity ʔ or t¬ t in “button” cotton, curtain, kitten, Clinton, continent, forgotten k c in “corn” c in “car”, k in “kill”, q in “queen”, copy, kin, quilt s s in “sandal” c in “cell” or s in “sell”, city, sinful, receive, fussy, so f f in “fan” f in “face” or ph in “phone” gh laugh, fit, photo, graph m m in “mouse” miss, camera, home, woman, dam, mb in “bomb” b b in “boot” bother, boss, baby, maybe, club, verb, born, snobby d d in “duck” dude, duck, daytime, bald, blade, dinner, sudden, do g g in “goat” go, guts, giggle, girlfriend, gift, guy, goat, globe, go z z in “zebra” zap, zipper, zoom, zealous, jazz, zucchini, zero v v in “van” very, vaccine, valid, veteran, achieve, civil, vivid n n in “nurse” never, nose, nice, sudden, tent, knife, knight, nickel l l in “lake” liquid, laugh, linger, -

Natural Phonetic Tendencies and Social Meaning: Exploring the Allophonic Raising Split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly

This is a repository copy of Natural phonetic tendencies and social meaning: Exploring the allophonic raising split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/133952/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Moore, E.F. and Carter, P. (2018) Natural phonetic tendencies and social meaning: Exploring the allophonic raising split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly. Language Variation and Change, 30 (3). pp. 337-360. ISSN 0954-3945 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394518000157 This article has been published in a revised form in Language Variation and Change [https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394518000157]. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © Cambridge University Press. Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Title: Natural phonetic tendencies -

A Study of Idiom Translation Strategies Between English and Chinese

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 3, No. 9, pp. 1691-1697, September 2013 © 2013 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.9.1691-1697 A Study of Idiom Translation Strategies between English and Chinese Lanchun Wang School of Foreign Languages, Qiongzhou University, Sanya 572022, China Shuo Wang School of Foreign Languages, Qiongzhou University, Sanya 572022, China Abstract—This paper, focusing on idiom translation methods and principles between English and Chinese, with the statement of different idiom definitions and the analysis of idiom characteristics and culture differences, studies the strategies on idiom translation, what kind of method should be used and what kind of principle should be followed as to get better idiom translations. Index Terms— idiom, translation, strategy, principle I. DEFINITIONS OF IDIOMS AND THEIR FUNCTIONS Idiom is a language in the formation of the unique and fixed expressions in the using process. As a language form, idioms has its own characteristic and patterns and used in high frequency whether in written language or oral language because idioms can convey a host of language and cultural information when people chat to each other. In some senses, idioms are the reflection of the environment, life, historical culture of the native speakers and are closely associated with their inner most spirit and feelings. They are commonly used in all types of languages, informal and formal. That is why the extent to which a person familiarizes himself with idioms is a mark of his or her command of language. Both English and Chinese are abundant in idioms. -

L Vocalisation As a Natural Phenomenon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Essex Research Repository L Vocalisation as a Natural Phenomenon Wyn Johnson and David Britain Essex University [email protected] [email protected] 1. Introduction The sound /l/ is generally characterised in the literature as a coronal lateral approximant. This standard description holds that the sounds involves contact between the tip of the tongue and the alveolar ridge, but instead of the air being blocked at the sides of the tongue, it is also allowed to pass down the sides. In many (but not all) dialects of English /l/ has two allophones – clear /l/ ([l]), roughly as described, and dark, or velarised, /l/ ([…]) involving a secondary articulation – the retraction of the back of the tongue towards the velum. In dialects which exhibit this allophony, the clear /l/ occurs in syllable onsets and the dark /l/ in syllable rhymes (leaf [li˘f] vs. feel [fi˘…] and table [te˘b…]). The focus of this paper is the phenomenon of l-vocalisation, that is to say the vocalisation of dark /l/ in syllable rhymes 1. feel [fi˘w] table [te˘bu] but leaf [li˘f] 1 This process is widespread in the varieties of English spoken in the South-Eastern part of Britain (Bower 1973; Hardcastle & Barry 1989; Hudson and Holloway 1977; Meuter 2002, Przedlacka 2001; Spero 1996; Tollfree 1999, Trudgill 1986; Wells 1982) (indeed, it appears to be categorical in some varieties there) and which extends to many other dialects including American English (Ash 1982; Hubbell 1950; Pederson 2001); Australian English (Borowsky 2001, Borowsky and Horvath 1997, Horvath and Horvath 1997, 2001, 2002), New Zealand English (Bauer 1986, 1994; Horvath and Horvath 2001, 2002) and Falkland Island English (Sudbury 2001). -

Reading Foundational Skills

Common Core State StandardS for engliSh language artS & literaCy in hiStory/SoCial StudieS, SCienCe, and teChniCal SubjeCtS reading Foundational skills The following supplements the Reading Standards: Foundational Skills (K–5) in the main document (pp. 14–16). See page 40 in the bibliography of this appendix for sources used in helping construct the foundational skills and the material below. Phoneme-Grapheme correspondences Consonants Common graphemes (spellings) are listed in the following table for each of the consonant sounds. Note that the term grapheme refers to a letter or letter combination that corresponds to one speech sound. Figure 8: Consonant Phoneme-Grapheme Correspondences in English Common Graphemes (Spellings) Phoneme Word Examples for the Phoneme* /p/ pit, spider, stop p /b/ bit, brat, bubble b /m/ mitt, comb, hymn m, mb, mn /t/ tickle, mitt, sipped t, tt, ed /d/ die, loved d, ed /n/ nice, knight, gnat n, kn, gn /k/ cup, kite, duck, chorus, folk, quiet k, c, ck, ch, lk, q /g/ girl, Pittsburgh g, gh /ng/ sing, bank ng, n /f/ fluff, sphere, tough, calf f, ff, gh, ph, lf /v/ van, dove v, ve /s/ sit, pass, science, psychic s, ss, sc, ps /z/ zoo, jazz, nose, as, xylophone z, zz, se, s, x /th/ thin, breath, ether th /th/ this, breathe, either th /sh/ shoe, mission, sure, charade, precious, notion, mission, sh, ss, s, ch, sc, ti, si, ci special /zh/ measure, azure s, z /ch/ cheap, future, etch ch, tch /j/ judge, wage j, dge, ge /l/ lamb, call, single l, ll, le /r/ reach, wrap, her, fur, stir r, wr, er/ur/ir /y/ you, use, feud, onion y, (u, eu), i /w/ witch, queen w, (q)u /wh/ where wh /h/ house, whole h, wh *Graphemes in the word list are among the most common spellings, but the list does not include all possible graph- emes for a given consonant.