Liskeard & Caradon Railway Survey 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

176 Exchange (Penzance), Rail Ale Trail, 114 43, 49 Seven Stones pub (St Index Falmouth Art Gallery, Martin’s), 168 Index 101–102 Skinner’s Brewery A Foundry Gallery (Truro), 138 Abbey Gardens (Tresco), 167 (St Ives), 48 Barton Farm Museum Accommodations, 7, 167 Gallery Tresco (New (Lostwithiel), 149 in Bodmin, 95 Gimsby), 167 Beaches, 66–71, 159, 160, on Bryher, 168 Goldfish (Penzance), 49 164, 166, 167 in Bude, 98–99 Great Atlantic Gallery Beacon Farm, 81 in Falmouth, 102, 103 (St Just), 45 Beady Pool (St Agnes), 168 in Fowey, 106, 107 Hayle Gallery, 48 Bedruthan Steps, 15, 122 helpful websites, 25 Leach Pottery, 47, 49 Betjeman, Sir John, 77, 109, in Launceston, 110–111 Little Picture Gallery 118, 147 in Looe, 115 (Mousehole), 43 Bicycling, 74–75 in Lostwithiel, 119 Market House Gallery Camel Trail, 3, 15, 74, in Newquay, 122–123 (Marazion), 48 84–85, 93, 94, 126 in Padstow, 126 Newlyn Art Gallery, Cardinham Woods in Penzance, 130–131 43, 49 (Bodmin), 94 in St Ives, 135–136 Out of the Blue (Maraz- Clay Trails, 75 self-catering, 25 ion), 48 Coast-to-Coast Trail, in Truro, 139–140 Over the Moon Gallery 86–87, 138 Active-8 (Liskeard), 90 (St Just), 45 Cornish Way, 75 Airports, 165, 173 Pendeen Pottery & Gal- Mineral Tramways Amusement parks, 36–37 lery (Pendeen), 46 Coast-to-Coast, 74 Ancient Cornwall, 50–55 Penlee House Gallery & National Cycle Route, 75 Animal parks and Museum (Penzance), rentals, 75, 85, 87, sanctuaries 11, 43, 49, 129 165, 173 Cornwall Wildlife Trust, Round House & Capstan tours, 84–87 113 Gallery (Sennen Cove, Birding, -

SHLAA2 Report Draft

Cornwall Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment Cornwall Council February 2015 1 Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................... 4 1.1 Background ................................................................................. 4 1.2 Study Area .................................................................................. 4 1.3 Purpose of this Report ................................................................... 5 1.4 Structure of the Report ................................................................. 6 2. Planning Policy Context ...................................................................... 7 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................. 7 2.2 National Planning Policy Framework (2012) ..................................... 7 2.3 Emerging Cornwall Local Plan ......................................................... 8 2.4 Determining Cornwall’s Housing Need ........................................... 10 2.5 Determining the Buffer for Non-Delivery ........................................ 11 2.6 Summary .................................................................................. 12 3. Methodology ................................................................................... 13 3.1 Introduction ............................................................................... 13 3.2 Baseline Date ............................................................................. 13 3.3 A Partnership -

The Distribution of Ammonium in Granites from South-West England

Journal of the Geological Society, London, Vol. 145, 1988, pp. 37-41, 1 fig., 5 tables. Printed in Northern Ireland The distribution of ammonium in granites from South-West England A. HALL Department of Geology, Royal Holloway and Bedford New College, Egham, Surrey TW20 OEX, UK Abstract: The ammonium contents of granites, pegmatites and hydrothermally altered rocks from SW England have been measured. Ammonium levels in the granites are generally high compared with those from other regions, averaging 36ppm,and they differ markedlybetween intrusions. The pegmatites show higherammonium contents than any other igneous rocks which have yet been investigated. Ammonium contents are strongly enriched in the hydrothermally altered rocks, includ- ing greisens and kaolinized granites. There is agood correlation between the average ammonium content of the intrusions in SW England and their initial "Sr/*'Sr ratios and peraluminosity. This relationship supports the hypothesis that the ammonium in the granites is derived from a sedimentary source, either in the magmatic source region or via contamination of the magma. Introduction Results Ammonium is present as a trace constituent of granitic The granites rocks, in which it occurs in feldspars and micas substituting isomorphously for potassium (Honma & Itihara 1981). The The new analyses of Cornubian granites are given in Table amount of ammonium in granites varies from zero to over 1. They show a range of 3-179 parts per million NH:, with 100 parts per million, and it has been suggested that high the highest values being found in relatively small intrusions. concentrations may indicate the incorporation of organic- Taking the averagefor each of the major intrusions,and rich sedimentary material into the magma, either from the weighting them according to their relative areas (see Table presence of such material in rhe magmatic source region or 4), the average ammonium contentof the Cornubian granites via the assimilation of organic-rich country rocks (Urano as a whole is 36 ppm. -

Patrieda Barn, Linkinhorne, Callington, Cornwall, PL17 7NA

Patrieda Barn, Linkinhorne, Callington, Cornwall, PL17 7NA PHOTO PHOTO PHOTO PHOTO REF: LA00003721 Patreida Barn, Linkinhorne, Callington, Cornwall, PL17 7NA 2 Broad Street Launceston Cornwall PL15 8AD FREEHOLD Tel: 01566 777 777 Fax: 01566 775 115 E: [email protected] Large 3 bedroom farmhouse located near the edge of Bodmin Moor Situated within a 4 acre plot. Biomass heating Spectacular views of Sharp Tor and Caradon Hill Located on a quiet rural lane Offices also at: Exeter 01392 252262 Holsworthy 01409 253888 Bude 01288 359999 Liskeard 01579 345543 Callington 01579 384321 Callington 5 miles Launceston 10 miles Kivells Limited, registered in England & Wales. Company number: 08519705. Registered office: 2 Barnfield Crescent, Plymouth 21 miles Exeter 49 miles Exeter, Devon, EX1 1QT SITUATION Although in a quiet rural location, the property is no more than 5 miles slate hearth and shelving to chimney breast recesses. away from all amenities. The local primary school is 3 miles away at Upton Cross which also has a small grocery store and post office. and INNER HALLWAY Slate floor, doors to all downstairs accommodation and stairs leading Callington Community College is 5 miles away in Callington which also benefits from a health centre, Tesco superstore and petrol station, to first floor. Spotlighting, radiator and sliding door giving access various shops, pubs and sporting facilities including St. Mellion to:- International golf course and leisure facilities. UTILITY ROOM Room for various appliances, slate floor, double glazed window to front elevation and built-in shelving. BATHROOM PHOTO DESCRIPTION Low level W.C., panelled bath with mixer shower attachments, This is an impressive traditional stone built property set in a beautiful pedestal wash hand basin and obscure double glazing to front location with outstanding views over Sharp Tor and Caradon Hill. -

15.A-Grant-Moor-To-Sea-App.Pdf

LISKEARD TOWN COUNCIL GRANT AWARDING POLICY Aim: Liskeard Town Council allocates a grants budget annually to assist other organisations within the town to achieve projects, services, exhibitions and events of benefit to the town and its residents. Eligibility Criteria to assist potential applicants and Councillors on the Finance, Economic Development & General Purposes Committee. • Applications can only be considered if they can demonstrate that the grant aid will be of benefit to the community of Liskeard. • Grants will only be given to non-profit making organisations. • All grant applications must be accompanied by the latest set of accounts, failing this, a current statement of the funds and balances. • An individual may not receive a grant, although a club or association can apply. • A single business cannot receive a grant, although a Trade Association or Chamber might put forward an eligible project. • Grants will not be awarded retrospectively to any project. • Grants will not be given for normal repairs or maintenance. • Grants will not be paid against the normal operating costs of an organisation, e.g. wages, rents, stock etc. • Normally awards of grant will be in the range of £50 - £500. For applications which the Committee considers are exceptional, the Committee can reserve the right to approve a grant of up to £5,000. The approval of a larger sum would need to be ratified by the Town Council under Financial Regulation 5.8 of the Revised Regulations adopted on 20 October 2015. • The money must be used within two years of being awarded. • Should a grant be awarded the Town Council requires as a condition of approval that the support of the Town Council is acknowledged in all relevant press releases, social media posts etc. -

Rivendell Cottage, Caradon View, Minions, Liskeard, Cornwall Pl14 5Ll Offers in Excess of £400,000

RIVENDELL COTTAGE, CARADON VIEW, MINIONS, LISKEARD, CORNWALL PL14 5LL OFFERS IN EXCESS OF £400,000 OPEN MOORLAND 1 MILE, LISKEARD 6 MILES, LAUNCESTON 10 MILES, LOOE AND THE BEACH 14 MILES Stunning moorland cottage with handsome granite elevations and moulded mullion windows, immediately adjacent to open moorland and with studio/annexe, parking and established gardens with fabulous views over the beautiful moorland landscape. About 1251 sq ft, Entrance Porch, 25' Sitting/Dining Room, 25' Kitchen/Breakfast Room, 4 Bedrooms (1 Ensuite Washroom/WC), Family Bathroom, Driveway Parking, Carport, 466 sq ft Studio Annexe, Pretty Gardens. LOCATION In an enviable setting on within the romantic landscape of Bodmin Moor, this setting is awash with scenic beauty and an abundance of wildlife. From the property one can observe stunning views over the beautiful countryside of South East Cornwall. The wide expanse of Bodmin Moor is immediately accessible and provides excellent opportunities for equestrians and those with outdoor interests. The property is situated on the outskirts of the popular village of Upton Cross, with amenities including a renowned primary school (rated "outstanding" by Ofsted) and a bus route which links the towns of Liskeard and Launceston. Nearby is the Caradon Inn public house and the internationally renowned Sterts open air theatre. Liskeard provides access to a substantial array of amenities including a main line railway station (Plymouth to London Paddington 3 hours). The University city of Plymouth is easily accessible and boasts a comprehensive range of premier retail outlets, entertainment and dining establishments set against the back drop of the historic waterside areas of The Hoe and the Barbican. -

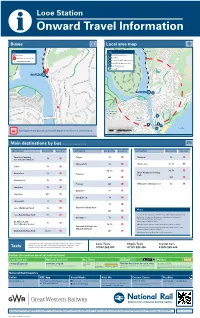

Looe Station I Onward Travel Information Buses Local Area Map

Looe Station i Onward Travel Information Buses Local area map Key Key To Liskeard A Bus Stop i Tourist Information Centre Rail replacement Bus Stop BT Boat Trips LS Local Shops, Pubs & Restaurants Station Entrance/Exit M Old Guildhall, Museum & Gaol PH Pub - The Globe Inn 10 Footpaths m in B A u te s w a Looe Station lk in g d i s t a n c e Looe Station PH C East To Polperro Looe and Pelynt LS West i Looe LS LS M km BT Looe Bay 0 0.5 Rail replacement buses/coaches will depart from the front of the station 0 Miles 0.25 Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Main destinations by bus (Data correct at September 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP Caradon Camping Pelynt 73 A Tideford 72 B 73 A (for Trelawne Manor) Plymouth X 72 B West Looe 72, 73 A Duloe 73 B 72, 73 A 72, 73 A West Waylands Holiday Hannafore 72 A Polperro Park 481 C 481 C Hessenford 72 B Polruan 481 C Widegates (Shortacross) 72 B Landrake 72 B Saltash X 72 B Lansallos 481 C Sandplace ^ 73 B Liskeard ^ 73 B 73 A Looe (Barbican Road) 72 B Seaview Holiday Park Notes 481 C Looe Bay Holiday Park 72 B Bus route 481 operates a limited service Mondays to Fridays only St Keyne [ 73 B Bus route 72 operates Mondays to Saturdays only towards Plymouth, daily towards Polperro No Man's Land Bus route 73 operates daily 72 B (for Polborder House) 72, 73 A ^ Direct trains operate to this destination from this station. -

74 – March 2021

74 Callington - Pensilvia - Liskeard 74/A/174 174 Upton Cross - Callywith College 74A Upton Cross - Liskeard Transport for Cornwall Timetable valid from 08/03/2021 until further notice. Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Service 74 174 74 74A 74 74 74 74 74 74 74 74 74 74 74 74 74 74 Service Restrictions SH Col Sch 1 SH Sch Sch SH Sch Callington, Callington School (W-bound) dep 0815 1510 Callington, New Road (N-bound) 0730 0730 0820 0820 0920 1015 1115 1215 1315 1415 1515 1545 1645 1740 1830 Callington, Lansdowne Road (W-bound) 0733 0733 0823 0823 0923 1018 1118 1218 1318 1418 1518 1548 1648 1743 1833 St Ive, opp Butchers Arms 0742 0742 0832 0832 0932 1027 1127 1227 1327 1427 1527 1557 1657 1752 1842 Upton Cross, Phone Box (W-bound) 0740 0750 Pensilva, The Cross (SE-bound) 0748 0748 0748 0758 0838 0838 0938 1033 1133 1233 1333 1433 1533 1603 1703 1758 1848 Pensilva, Glen Park (W-bound) 0750 0750 0750 0800 0840 0840 0940 1035 1135 1235 1335 1435 1535 1605 1705 1800 1850 Crows Nest, opp Crows Nest Inn 0753 0753 0753 0843 0843 0943 1038 1138 1238 1338 1438 1538 1608 1708 1803 1853 Darite, Telephone Box (SW-bound) 0756 0756 0756 0846 0846 0946 1041 1141 1241 1341 1441 1541 1611 1711 1806 1856 St Cleer, opp Market Inn 0803 0803 0803 0853 0853 0953 1048 1148 1248 1348 1448 1548 1618 1718 1813 1903 Tremar, Telephone Box (SE-bound) 0806 0806 0806 0856 0856 0956 1051 1151 1251 1351 1451 1551 1621 1721 1816 1906 Liskeard, opp Trevecca Cottages -

Cornwall Council Altarnun Parish Council

CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Baker-Pannell Lisa Olwen Sun Briar Treween Altarnun Launceston PL15 7RD Bloomfield Chris Ipc Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SA Branch Debra Ann 3 Penpont View Fivelanes Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY Dowler Craig Nicholas Rivendale Altarnun Launceston PL15 7SA Hoskin Tom The Bungalow Trewint Marsh Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TF Jasper Ronald Neil Kernyk Park Car Mechanic Tredaule Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RW KATE KENNALLY Dated: Wednesday, 05 April, 2017 RETURNING OFFICER Printed and Published by the RETURNING OFFICER, CORNWALL COUNCIL, COUNCIL OFFICES, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Kendall Jason John Harrowbridge Hill Farm Commonmoor Liskeard PL14 6SD May Rosalyn 39 Penpont View Labour Party Five Lanes Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY McCallum Marion St Nonna's View St Nonna's Close Altarnun PL15 7RT Richards Catherine Mary Penpont House Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SJ Smith Wes Laskeys Caravan Farmer Trewint Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TG The persons opposite whose names no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. -

CORNWALL Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph CORNWALL Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No Parish Location Position CW_BFST16 SS 26245 16619 A39 MORWENSTOW Woolley, just S of Bradworthy turn low down on verge between two turns of staggered crossroads CW_BFST17 SS 25545 15308 A39 MORWENSTOW Crimp just S of staggered crossroads, against a low Cornish hedge CW_BFST18 SS 25687 13762 A39 KILKHAMPTON N of Stursdon Cross set back against Cornish hedge CW_BFST19 SS 26016 12222 A39 KILKHAMPTON Taylors Cross, N of Kilkhampton in lay-by in front of bungalow CW_BFST20 SS 25072 10944 A39 KILKHAMPTON just S of 30mph sign in bank, in front of modern house CW_BFST21 SS 24287 09609 A39 KILKHAMPTON Barnacott, lay-by (the old road) leaning to left at 45 degrees CW_BFST22 SS 23641 08203 UC road STRATTON Bush, cutting on old road over Hunthill set into bank on climb CW_BLBM02 SX 10301 70462 A30 CARDINHAM Cardinham Downs, Blisland jct, eastbound carriageway on the verge CW_BMBL02 SX 09143 69785 UC road HELLAND Racecourse Downs, S of Norton Cottage drive on opp side on bank CW_BMBL03 SX 08838 71505 UC road HELLAND Coldrenick, on bank in front of ditch difficult to read, no paint CW_BMBL04 SX 08963 72960 UC road BLISLAND opp. Tresarrett hamlet sign against bank. Covered in ivy (2003) CW_BMCM03 SX 04657 70474 B3266 EGLOSHAYLE 100m N of Higher Lodge on bend, in bank CW_BMCM04 SX 05520 71655 B3266 ST MABYN Hellandbridge turning on the verge by sign CW_BMCM06 SX 06595 74538 B3266 ST TUDY 210 m SW of Bravery on the verge CW_BMCM06b SX 06478 74707 UC road ST TUDY Tresquare, 220m W of Bravery, on climb, S of bend and T junction on the verge CW_BMCM07 SX 0727 7592 B3266 ST TUDY on crossroads near Tregooden; 400m NE of Tregooden opp. -

Mar-Apr 2010

St Martin-By-Looe News Published and funded by St Martin-By-Looe Parish Council Mar/Apr 2010 Parish Council Update Planning Applications Applications for the construction of a specialist disabled-use holiday cottage at Higher Treveria, No Man’s Land, an extension to the bungalow at Cosy Nook, Cliff Valley Farm, St Martin’s and the construction of 20 affordable/local needs houses at land adjacent to The Coach House, Shortacross, Widegates were all considered by the Parish Council during the January meeting; none were received in February. Donations Requests from Tanya’s Courage Trust, supporting young peo- ple with cancer in Cornwall and The Cornwall Blind Association, resulted £50 being donated to each organisation. Police Report Since the last report dated 3rd December 2009, a total of 94 crimes have been reported within the area covered by Looe Neighbourhood Team. One of the crimes, (unauthorised taking of a motor vehicle) was reported within the Parish. On January 15th 2010 two searches under MUDA were carried out at two addresses in East Looe. Two females were arrested for posses- sion of a class A drug. PCSO DAVE BILLING 30281 Salt Bins at Millendreath A request has been made for the Parish Council to supply two salt bins for Millendreath; approval has been sought from Corn- wall Council and a decision should be made in the summer. Meeting Dates You are always welcome to attend the Parish Council Meetings. The next meetings are March 4th and April 1st. Public participa- tion is welcome before the meeting starts. 1 Tredinnick Farm Shop & Tea Rooms Widegates, Near Looe, Cornwall Local Fruit and Vegetables Fresh meat Farm scrumpy, beers and wines Home made preserves and local honey Fresh bread, cakes, pasties and pies Organic Cornish Ice Creams Open 7 days per week 9am - 6pm Monday - Saturday 0am - 5pm Sunday Tel: 01503 240992 Signposted on the A387 between Hessenford and Looe Under new management. -

The Micro-Geography of Nineteenth Century Cornish Mining?

MINING THE DATA: WHAT CAN A QUANTITATIVE APPROACH TELL US ABOUT THE MICRO-GEOGRAPHY OF NINETEENTH CENTURY CORNISH MINING? Bernard Deacon (in Philip Payton (ed.), Cornish Studies Eighteen, University of Exeter Press, 2010, pp.15-32) For many people the relics of Cornwall’s mining heritage – the abandoned engine house, the capped shaft, the re-vegetated burrow – are symbols of Cornwall itself. They remind us of an industry that dominated eighteenth and nineteenth century Cornwall and that still clings on stubbornly to the margins of a modern suburbanised Cornwall. The remains of this once thriving industry became the raw material for the successful World Heritage Site bid of 2006. Although the prime purpose of the Cornish Mining World Heritage Site team is to promote the mining landscapes of Cornwall and west Devon and the Cornish mining ‘brand’, the WHS website also recognises the importance of the industrial and cultural landscapes created by Cornish mining in its modern historical phase from 1700 to 1914.1 Ten discrete areas are inscribed as world heritage sites, stretching from the St Just mining district in the far west and spilling over the border into the Tamar Valley and Tavistock in the far east. However, despite the use of innovative geographic information system mapping techniques, visitors to the WHS website will struggle to gain a sense of the relative importance of these mining districts in the history of the industry. Despite a rich bibliography associated with the history of Cornish mining the historical geography of the industry is outlined only indirectly.2 The favoured historiographical approach has been to adopt a qualitative narrative of the relentless cycle of boom and bust in nineteenth century Cornwall.