Center‐Periphery Bargaining in the Age Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swiss Family Hotels & Lodgings

Swiss Family Hotels & Swiss Family Hotels & Lodgings 2019. Lodgings. MySwitzerland.com Presented by Swiss Family Hotels & Lodgings at a glance. Switzerland is a small country with great variety; its Swiss Family Hotels & Lodgings are just as diverse. This map shows their locations at a glance. D Schaffhausen B o d e n A Aargau s Rhein Thur e e Töss Frauenfeld B B Basel Region Limm at Liestal Baden C irs Bern B Aarau 39 St-Ursanne Delémont Herisau Urnäsch D F A Appenzell in Fribourg Region Re 48 e 38 h u R ss Säntis Z 37 H ü 2502 r i c Wildhaus s Solothurn 68 E ub h - s e e Geneva o 49 D e L Zug Z 2306 u g Churfirsten Aare e Vaduz r W s a e La Chaux- 1607 e lense F e L 47 Lake Geneva Region Chasseral i de-Fonds e 44 n Malbun e s 1899 t r h e 1798 el Grosser Mythen Bi Weggis Rigi Glarus G Graubünden Vierwald- Glärnisch 1408 42 Schwyz 2914 Bad Ragaz Napf 2119 Pizol Neuchâtel are stättersee Stoos A Pilatus 43 Braunwald 46 2844 l L te Stans an H hâ d Jura & Three-Lakes c qu u Sarnen 1898 Altdorf Linthal art Klosters Ne Stanserhorn R C Chur 2834 24 25 26 de e Flims ac u Weissfluh Piz Buin L 2350 s 27 Davos 3312 32 I E 7 Engelberg s Tödi 23 Lucerne-Lake Lucerne Region mm Brienzer 17 18 15 e Rothorn 3614 Laax 19 20 21 Scuol e 40 y 45 Breil/Brigels 34 35 Arosa ro Fribourg Thun Brienz Titlis Inn Yverdon B 41 3238 a L D rs. -

Bernese Anabaptist History: a Short Chronological Outline (Jura Infos in Blue!)

Bernese Anabaptist History: a short chronological outline (Jura infos in blue!) 1525ff Throughout Europe: Emergence of various Anabaptist groups from a radical reformation context. Gradual diversification and development in different directions: Swiss Brethren (Switzerland, Germany, France, Austria), Hutterites (Moravia), Mennonites [Doopsgezinde] (Netherlands, Northern Germany), etc. First appearance of Anabaptists in Bern soon after 1525. Anabaptists emphasized increasingly: Freedom of choice concerning beliefs and church membership: Rejection of infant baptism, and practice of “believers baptism” (baptism upon confession of faith) Founding of congregations independent of civil authority Refusal to swear oaths and to do military service “Fruits of repentance”—visible evidence of beliefs 1528 Coinciding with the establishment of the Reformation in Bern, a systematic persecution of Anabaptists begins, which leads to their flight and migration into rural areas. Immediate execution ordered for re-baptized Anabaptists who will not recant (Jan. 1528). 1529 First executions in Bern (Hans Seckler and Hans Treyer from Lausen [Basel] and Heini Seiler from Aarau) 1530 First execution of a native Bernese Anabaptist: Konrad Eichacher of Steffisburg. 1531 After a first official 3-day Disputation in Bern with reformed theologians, well-known and successful Anabaptist minister Hans Pfistermeyer recants. New mandate moderates punishment to banishment rather than immediate execution. An expelled person who returns faces first dunking, and if returning a second time, death by drowning . 1532 Anabaptist and Reformed theologians meet for several days in Zofingen: Second Disputation. Both sides declare a victory. 1533 Further temporary moderation of anti-Anabaptist measures: Anabaptists who keep quiet are tolerated, and even if they do not, they no longer face banishment, dunking or execution, but are imprisoned for life at their own expense. -

The Land of the Tüftler – Precision Craftsmanship Through the Ages

MAGAZINE ON BUSINESS, SCIENCE AND LIVING www.berninvest.be.ch Edition 1/2020 IN THE CANTON OF BERN, SWITZERLAND PORTRAIT OF A CEO Andrea de Luca HIDDEN CHAMPION Temmentec AG START-UP Four new, ambitious companies The Land of the Tüftler – introduce themselves Precision Craftsmanship LIVING / CULTURE / TOURISM Espace découverte Énergie – the art Through the Ages of smart in using nature’s strengths Get clarity The Federal Act on Tax Reform and AHV Financing (TRAF) has transformed the Swiss tax landscape. The changes are relevant not only for companies that previously enjoyed cantonal tax status, but all taxpayers in general. That’s why it’s so important to clarify the impact of the reform on an individual basis and examine applicability of the new measures. Our tax experts are ready to answer your questions. kpmg.ch Frank Roth Head Tax Services Berne +41 58 249 58 92 [email protected] © 2020 KPMG AG is a Swiss corporation. All rights reserved. corporation. is a Swiss AG © 2020 KPMG klarheit_schaffen_inserat_229x324_0320_en_v3.indd 1 19.03.20 16:08 Content COVER STORY 4–7 The Land of the Tüftler – Get clarity Precision Craftsmanship Through the Ages START-UP 8/9 Cleveron legal-i The Federal Act on Tax Reform and AHV Financing (TRAF) has Moskito Watch transformed the Swiss tax landscape. The changes are relevant not Dokoki only for companies that previously enjoyed cantonal tax status, but all taxpayers in general. PORTRAIT OF A CEO 10/11 Andrea de Luca That’s why it’s so important to clarify the impact of the reform on HIDDEN CHAMPION 12/13 an individual basis and examine applicability of the new measures. -

Contribution À L'étude Des Cluses Du Jura Septentrional

Université de Neuchâtel Institut de géologie Contribution à l'étude des cluses du Jura septentrional Thèse présentée à (a Faculté des sciences de l'Université de Neuchâtel par Michel Monbaron Licencié es sciences Avril 1975 Imprimerie Genodruck, Bienne IMPRIMATUR POUR LA THESE Contribution al Jura septentrional deMQns.i.eur....Mii:hel...JïlDZLhar.Qn. UNIVERSITÉ DE NEUCHATEL FACULTÉ DES SCIENCES La Faculté des sciences de l'Université de Neuchâtel, sur le rapport des membres du jury, .Ml*...ae.s....px.QÍfis.s.eur.s....D*..Jiub.ert.+...P>...XMu.Y£.„„ _(BêSan£QrJ^_J_c£ autorise l'impression de la présente thèse sans exprimer d'opinion sur les propositions qui y sont contenues. Neuchâtel, le 9.~ms,xs....l9l6. Le doyen : P. Huguenin Thèse publiée avec l'appui de : l'Etat de Neuchâtel et l'Etat de Berne. Ce travail a obtenu Le Prix des Thèses 1976 de la Société Jurassienne d'Emulation. IV RESUME Une cluse jurassienne caractéristique, celle du Pichoux, est étudiée sous divers aspects. La localisation de la cluse dans l'anticlinal de Raimeux dépend en premier lieu d'un ensellement- d'axe au toit de l'imperméable oxfordien, ainsi que d'un relais axial dans le coeur de Dogger. Les systèmes de fissuration, principalement les deux sys tèmes cisaillants dextre et sénestre, ont fourni la trame sur laquel le s'est imprimée la cluse. Hydrogéologiquement, celle-ci fait office de niveau de base karstique pour de vastes territoires situés surtout à l'W ("bordure orientale des Franches-Montagnes). La principale sour ce karstique qui y jaillit est celle de Blanches Fontaines: surface du bassin 48,8 km^; débit moyen annuel 1,25 m3/sec; valeur moyenne de l'ablation karstique totale: 0,082 mm/an. -

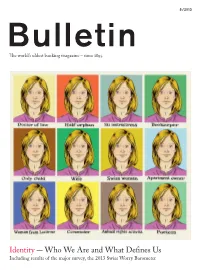

Identity - Who We Are and What Defines Us Including Results of the Major Survey, the 2013 Swiss Worry Barometer T H E Art of Progress

5 / 2013 Bulletin The world’s oldest banking magazine – since 1895. Identity - Who We Are and What Defines Us Including results of the major survey, the 2013 Swiss Worry Barometer T h e Art of progress. The new Audi A8. The art of breaking new ground in design and dynamics with lightweight engineering. Experience the technique of reducing the weight of wheels using new materials and thereby realising new potential savings. The 20" technology wheel* of the new Audi A8. More at www.audi.ch/a8 * optional feature — Editorial — Identity Is a ManyFaceted Thing 1 2 3 4 hether for individuals or groups, to build up a sense of self or differentiate from others, the act of defining identity strikes a chord with everyone and opens the emotional floodgates. The struggle to define the self is at the heart The following people contributed to this issue: W of every personal biography and, for better or worse, has shaped global history. his issue of Bulletin examines identity in Switzerland. 1 Yves Genier Knowing that a country cannot have one single identity, The Swiss business journalist is experiencing we explore various aspects of what it means to be Swiss. the upswing in the Lake Geneva region, up For example, what is still Swiss about the emigrants who were close and personal. Genier, 47, has always T lived between Geneva and Lausanne. His driven out of the country for economic reasons more than 70 report on Arc Lémanique starts on page 28 years ago and settled in northern Argentina (see page 56)? How are the economic recovery and internationalization changing the 2 Monika Bütler Arc Lémanique, the booming region on Lake Geneva (page 28)? The economics professor at the University of On page 20, we look into the phenomenon of how social insur St. -

Switzerland – a Model for Solving Nationality Conflicts?

PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE FRANKFURT Bruno Schoch Switzerland – A Model for Solving Nationality Conflicts? Translation: Margaret Clarke PRIF-Report No. 54/2000 © Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF) Summary Since the disintegration of the socialist camp and the Soviet Union, which triggered a new wave of state reorganization, nationalist mobilization, and minority conflict in Europe, possible alternatives to the homogeneous nation-state have once again become a major focus of attention for politicians and political scientists. Unquestionably, there are other instances of the successful "civilization" of linguistic strife and nationality conflicts; but the Swiss Confederation is rightly seen as an outstanding example of the successful politi- cal integration of differing ethnic affinities. In his oft-quoted address of 1882, "Qu’est-ce qu’une nation?", Ernest Renan had already cited the confederation as political proof that the nationality principle was far from being the quasi-natural primal ground of the modern nation, as a growing number of his contemporaries in Europe were beginning to believe: "Language", said Renan, "is an invitation to union, not a compulsion to it. Switzerland... which came into being by the consent of its different parts, has three or four languages. There is in man something that ranks above language, and that is will." Whether modern Switzerland is described as a multilingual "nation by will" or a multi- cultural polity, the fact is that suggestions about using the Swiss "model" to settle violent nationality-conflicts have been a recurrent phenomenon since 1848 – most recently, for example, in the proposals for bringing peace to Cyprus and Bosnia. However, remedies such as this are flawed by their erroneous belief that the confederate cantons are ethnic entities. -

Guide Touristique 2017 Touristische Attraktionen Tourist Guide 2

BIEL/BIENNE SEELAND GUIDE TOURISTIQUE 2017 TOURISTISCHE ATTRAKTIONEN TOURIST GUIDE 2 9 11 11 4 3 3 8 8 Touristen-Information | Informations touristiques | Tourist Information Bahnlinien | Voies ferrées | Railway lines Wanderwege | Chemins pédestres | Hiking trails Radwege | Pistes cyclables | Cycling trails Schifffahrtslinien | Lignes de bateaux | Shipping lines Burgen, Schlösser | Châteaux | Castles Camping | Campings | Camp sites Strandbäder | Plages | Beaches 3 9 2 1 2 7 2 1 2 4 7 5 6 6 Siehe Seiten | voir pages | see pages: 32–37, 42–43 Mehr Routen und Informationen unter | routes et informations supplémentaires sur | more routes and information at: 5 www.schweizmobil.ch 4 TOURISMUS BIEL SEELAND TOURISME BIENNE SEELAND HIGHLIGHTS Grosses erleben auf kleinem Raum. Weitschweifende Möglichkeiten zum ST. PETERSINSEL Greifen nah. Das Seeland bietet Ferien vom Feinsten und Freizeit, L’ILE ST-PIERRE die ihren Namen verdient. Unser Gästeführer bringt Ihnen all diese Angebote 10 der Region Biel Seeland näher. Sie finden darin zahlreiche Vorschläge, ST. PETER’S ISLAND die Ihnen bei der Planung einer Reise oder eines Ausfluges sowie direkt vor Ort dienen. SCHIFF IN SICHT EN BATEAU S’IL VOUS PLAÎT Vivez la grande aventure à échelle humaine. Des possibilités sans fin sont 18 WELCOME ABOARD à portée de main. La région Bienne Seeland vous propose des vacances enchanteresses et des vrais loisirs. Cette brochure vous présente les nom- breux atouts touristiques de Bienne et du Seeland et vous aidera à planifier STAND UP PADDLING vos vacances ou votre excursion dans nos contrées. 20 Enjoy great experiences in this small region, with endless possibilities within your reach. The Seeland region offers the finest vacations and opportunities KANU for recreation. -

Jura Bernois

JURA BERNOIS MÉTAIRIES ET AUBERGES DE CAMPAGNE BERG- UND LANDGASTHÖFE FARM RESTAURANTS AND COUNTRY INNS MÉTAIRIES ET AUBERGES DE CAMPAGNE BERG- UND LANDGASTHÖFE FARM RESTAURANTS AND COUNTRY INNS FASCINANTES MÉTAIRIES L’histoire de la cinquantaine de métairies dans le Jura bernois remonte au XIVe siècle. Autrefois, elles servaient aux nombreuses communes alentour d’espace d’estivage pour le bétail. Les habitants des métairies ont su développer des stratégies particulières pour lutter contre les conditions climatiques rudes et l’isolement. C’est ainsi que sont nées des coutumes et des traditions qui perdurent aujourd’hui encore dans les métairies et qui sont transmises aux visiteurs. Il est ainsi possible d’assister à la fabrication traditionnelle du fromage d’alpage ou de goûter la gentiane maison. FASZINATION MÉTAIRIES Die Geschichte der über 50 Métairies im Berner Jura geht bis ins 14. Jahrhundert zurück. Früher dienten sie den zahlreichen Gemeinden in der Umgebung als Sömmerungsge- biet für ihr Vieh. Die Bewohner der Métairies entwickelten dabei spezielle Strategien gegen die harschen klimatischen Bedingungen und die Abgeschiedenheit. Daraus ents- tanden Bräuche und Traditionen, welche in den Métairies auch heute noch gelebt, und an Gäste weitergegeben werden. So ist es beispielsweise möglich, der traditionellen Alpkäseherstellung beizuwohnen oder den selbst gebrannten Enzianschnaps zu kosten. THE FASCINATION OF «MÉTAIRIES» The history of the over 50 "métairies" (small farms worked by share-croppers) in the Bernese Jura dates back to the 14th century. In the past, the numerous local communi- ties in the area used them as summer pasture for their cattle. The occupants of the "mé- tairies" developed special strategies for withstanding the harsh climate and the remote- ness. -

Guidebook to Direct Democracy 2008 Edition

2008 Guidebook to Direct Democracy 2008 edition analysis & opinion • essays • facts & presentations • factsheets • glossary & world survey the initiative & referendum institute europe “Loosely borrowing from Churchill: ‘Direct democracy is the worst kind of democracy – Guidebook to Direct Democracy except for all the others’.” roger de weck, writer in switzerlan d and beyond “This is the clearest and most succinct book I have read about direct democracy. The IRI Guidebook describes in precise detail how direct law-making by the voters works in Switzerland and beyond, through initiative and referendum, and shows where else in the world it is taking root.” brian beedham, the economist Never before have so many people been able to vote on substantive issues. Since the in switzerland and beyond millennium, more and more countries around the world have begun to use referendums in addition to elections, and more and more people now have the possibility of exerting an influence on the political agenda by means of a right of initiative. Throughout the world, representative democracy is being reformed and modernised. Existing indirect decision- making structures are being revitalised and given greater legitimacy by the addition of direct-democratic procedures and practice. The 2008 Edition of the IRI Guidebook addresses the key issues raised during the transition to modern democracy. It offers both an introduction to and a deepening of knowledge of the world of citizen lawmaking. Features include essays on the everyday practice of direct democracy in Switzerland, Europe and the world. Factsheets include background data on many aspects of the initiative & referendum process, and a new global survey maps both procedures and practice across the world, including hotspots such as the German “Länder” and first-time referendum practitioners in countries like Costa Rica and Thailand. -

Magazine Bernecapitalarea

Edition 2/2014 www.berneinvest.com Conversation Suzanne Thoma, CEO of BKW Business Key locational advantage Sylvac SA in Malleray Research & Development Where the sun is at center stage InnoCampus Biel and CSEM Living Citizens of the world An expat family in Bern Contents / editorial 3 Conversation 4/5 “BKW is reinventing itself” An interview with Dr. Suzanne Thoma Business 6–8 Key locational advantage Sylvac SA in Malleray 9–11 Exploring design in Oberaargau Switzerland – your Design Tour Langenthal Research & Development future business 12/13 Where the sun is at center stage InnoCampus Biel and CSEM 14–16 Innovative university know-how makes the running location Haute Ecole Arc Ingénierie Dear reader, KPMG in Switzerland supports you with Living As Minister of Economic Affairs of the Canton of Bern I am committed to ensuring that the canton plays a driving and experienced specialists. We provide valuable 17–19 Citizens of the world formative role in the region that is home to Switzerland’s local knowledge and assist you in your market An expat family in Bern capital city. In doing so our priority is to implement key entry. Our experts help you with setting up your 20 Ice-skating magic with a panoramic view projects and represent our interests more rigorously at the company as well as managing tax and legal Top of Europe ICE MAGIC Interlaken national level. requirements. Competition A project that will benefit industry throughout Switzerland is our candidacy for a network location of the national Swiss 21 Wellness weekend in Interlaken Hans Jürg Steiner, Partner Innovation Park in Biel, which we launched this spring. -

Zur Kritik Einiger Thalformen Und Thalnamen Der Schweiz. A. Combe

Zur Kritik einiger Thalformen und Thalnamen der Schweiz. Von Jakob Früh. (Hierzu Tafel 3.) A. Combe, Ruz und Cluse. 1. Einbürgerung des Begriffes Combe. Die von den Jurassiern längst unterschiedenen Begriffe combe, crêt, cluse, ruz sind zuerst von J. Thurmann 1832 in seinem „Essai sur les soul ē vements jurassiques du Porrentruy" in die wissenschaftliche Terminologie eingeführt worden 1). Zwei äus- sere Umstände verleihen dieser Arbeit ohne weiteres eine hohe Bedeut- ung. Einmal enthält das Untersuchungsgebiet Thurmanns, etwa Duf. VII umfassend, sämtliche geologischen und topographischen Eigentümlichkeiten des schweizerischen Jura; dann verfügte der Autor über eine Karte in 1: 96000, welche das Dufourblatt in mancher Hinsicht übertrifft). Für Thurmann sind die. Falten ver- tikale Hebungen. Die einfachen, ganzen Gewölbe sind Hebungen erster Ordnung (Chaumont) 3); le soulèvement du second ordre ist ein bis auf den Dogger aufgebrochenes Gewölbe (Chasseral, Vellerat- kette, Blauen). Es zeigt ein von zwei oberjurassischen Kämmen oder Gräten (crēt, patois „al ētre") flankiertes Antiklinalthal, auf dessen Grund Oxfordmergel oder Oolith anstehen. Sehr bezeichnend für diese Struktur ist der deutsche Name „Zwischenberg" E der Röthi-fluh (top. Atlas Bl. 112)' ). Das ist eine Combe und in diesem Falle eine Oxfordcombe. Die Tbalenden sind häufig Cirken (cir- ') Extrait des Memoires de la soc. d'hist. nat. de Strasbourg 1832. 4°. 84 p. 5 pl. 2) Buchwalder, Garte de l'ancien ēvêché de Bäte 1815-19. 3) Vgl. Abb. in Siegfried, der schweiz. Jura. Zür. 1851, p. 66 u. 238. me li 4) Vgl. Rollier, Mat. pour la carte g ēol. de la Baisse, 8ē ^rr. I stippt. 1893 p. 79. -

(EUROPP) Blog: the Last Piece of the Puzzle? Making Sense of the Swiss Town of Moutier’S Decision to Leave the Canton Page 1 of 4 of Bern

LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog: The last piece of the puzzle? Making sense of the Swiss town of Moutier’s decision to leave the canton Page 1 of 4 of Bern The last piece of the puzzle? Making sense of the Swiss town of Moutier’s decision to leave the canton of Bern The Swiss town of Moutier has voted to leave the canton of Bern and join the neighbouring canton of Jura. Sean Mueller explains the complex history surrounding the decision. On 28 March, a majority of 55% of voters in the Swiss town of Moutier decided to leave the canton of Bern behind and join the canton of Jura. You are forgiven for thinking we have all been here before, for we have – almost four years ago. A slightly smaller majority of voters reached the same conclusion in the summer of 2017, but that result was later cancelled because too many irregularities had taken place before and during the vote. The voting booth is no stranger in this corner of the world, but more so than elsewhere in Switzerland, Moutier is connected to some peculiarly heated issues. History, identity and canton-building First, some context. The choice facing voters on 28 March was between Jura, with its 74,000 inhabitants, and Bern, with over a million (Figure 1). But why do voters have strong feelings about the cantons they are part of in the first place? The 26 Swiss cantons are the historical, legal, political and social foundation of the Swiss federation. Most of them were there long before contemporary Switzerland was created in 1848.