Syntrophic Degradation of Cadaverine by a Defined Methanogenic Coculture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Author Version (PDF)

Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry Accepted Manuscript This is an Accepted Manuscript, which has been through the Royal Society of Chemistry peer review process and has been accepted for publication. Accepted Manuscripts are published online shortly after acceptance, before technical editing, formatting and proof reading. Using this free service, authors can make their results available to the community, in citable form, before we publish the edited article. We will replace this Accepted Manuscript with the edited and formatted Advance Article as soon as it is available. You can find more information about Accepted Manuscripts in the Information for Authors. Please note that technical editing may introduce minor changes to the text and/or graphics, which may alter content. The journal’s standard Terms & Conditions and the Ethical guidelines still apply. In no event shall the Royal Society of Chemistry be held responsible for any errors or omissions in this Accepted Manuscript or any consequences arising from the use of any information it contains. www.rsc.org/obc Page 1 of 26 Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry Comparison of alternative nucleophiles for Sortase A-mediated bioconjugation and application in neuronal cell labelling Samuel Baera, Julie Nigro a,b, Mariusz P. Madej a, Rebecca M. Nisbet a,b, Randy Suryadinata a, Gregory Coia a, Lisa P. T. Hong a, Timothy E. Adams a, Charlotte C. Williams *a†, Stewart D. Nuttall a,b†. Manuscript aCSIRO Materials Science and Engineering, 343 Royal Parade, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, AUSTRALIA. bPreventative Health Flagship, 343 Royal Parade, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, AUSTRALIA. *Correspondence to: Charlotte C. Williams ([email protected] ) at CSIRO Materials Accepted Science and Engineering, 343 Royal Parade, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, AUSTRALIA; Ph: +61 3 9662 7100). -

Anaerobic Microbial LCFA Degradation in Bioreactors

Presented in Session PP3A – Bio-electrochemical Processes 11th IWA World Congress on Anaerobic Digestion 23-27 September 2007 Brisbane, Australia Anaerobic microbial LCFA degradation in bioreactors D.Z. Sousa*, M.A. Pereira*, J.I. Alves*, H. Smidt**, A.J.M. Stams**, M.M. Alves* * Institute for Biotechnology and Bioengineering, Center for Biological Engineering, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal (E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]) ** Laboratory of Microbiology, Wageningen University, Hesselink van Suchtelenweg 4, 6703 CT Wageningen, The Netherlands Abstract This paper reviews recent results obtained on long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) anaerobic degradation. Two LCFA were used as model substrates: oleate, a mono-unsaturated LCFA, and palmitate, a saturated LCFA, both abundant in LCFA-rich wastewaters. 16S rRNA gene analysis of sludge samples submitted to continuous oleate- and palmitate-feeding followed by batch degradation of the accumulated LCFA demonstrated that bacterial communities were dominated by members of the Clostridiaceae and Syntrophomonadaceae families. Archaeal populations were mainly comprised of hydrogen-consuming microorganisms belonging to the genus Methanobacterium, and acetate- utilizers from the genera Methanosaeta and Methanosarcina. Enrichment cultures growing on oleate and palmitate, in the absence or presence of sulfate, gave more insight into the major players involved in the degradation of unsaturated and saturated LCFA. Syntrophomonas-related species were identified as predominant microorganisms in all the enrichment cultures. Microorganisms clustering within the family Syntrophobacteraceae were identified in the methanogenic and sulfate-reducing enrichments growing on palmitate. Distinct bacterial consortia were developed in oleate and palmitate enrichments, and observed differences might be related to the different degrees of saturation of these two LCFA. -

Role of Cadaverine and Piperidine in the Formation of N-Nitrosopiperidine in Heated Cured Meat

ROLE OF CADAVERINE AND PIPERIDINE IN THE FORMATION OF N-NITROSOPIPERIDINE IN HEATED CURED MEAT Drabik-Markiewicz G.1, 2, De Mey E. 1, Impens S. 1, Kowalska T. 2, Vander Heyden Y. 3 and Paelinck H.1* 1Research Group for Technology and Quality of Animal Products, Catholic University College Gent, Technology Campus Gent, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, 1 Gebroeders Desmetstraat, 9000 Gent, Belgium 2University of Silesia, Institute of Chemistry, 9 Szkolna Street, 40-006 Katowice, Poland 3Analytical Chemistry and Pharmaceutical Technology, Center for Pharmaceutical Research (CePhaR), Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), Laarbeeklaan 103, B-1090 Brussels, Belgium *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract — N-nitrosamines are carcinogenic compounds, which formation in meat products depends from different factors e.g., temperature, storage time, precursors and/or added sodium nitrite. Sodium nitrite is important for meat processing as curing agent. The aim of this study was to determine the role of cadaverine and piperidine on the formation of N-nitrosamines in heated cured meat products. Such experimental products were processed with different amounts of sodium nitrite ( 0 mg kg -1, 120 mg kg -1, 480 mg kg -1), 1000 mg kg -1 of cadaverine or 10 mg kg -1 of piperidine, and heated at 85°C, 120°C, 160°C or 220°C. Experimental evidence was produced using gas chromatography in combination with Thermal Energy Analyzer (GC-TEA). The obtained analytical results were statistically evaluated by means of the Univariate Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) approach. In the current study only N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) and N-nitrosopiperidine (NPIP) were detected. -

Article the Bee Hemolymph Metabolome: a Window Into the Impact of Viruses on Bumble Bees

Article The Bee Hemolymph Metabolome: A Window into the Impact of Viruses on Bumble Bees Luoluo Wang 1,2, Lieven Van Meulebroek 3, Lynn Vanhaecke 3, Guy Smagghe 2 and Ivan Meeus 2,* 1 Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Insect Developmental Biology and Applied Technology, Institute of Insect Science and Technology, School of Life Sciences, South China Normal University, Guangzhou, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Plants and Crops, Faculty of Bioscience Engineering, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium; [email protected], [email protected] 3 Laboratory of Chemical Analysis, Department of Veterinary Public Health and Food Safety, Faculty of Vet- erinary Medicine, Ghent University, Merelbeke, Belgium; [email protected]; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Selection of the targeted biomarker set: In total we identified 76 metabolites, including 28 amino acids (37%), 11 carbohy- drates (14%), 11 carboxylic acids, 2 TCA intermediates, 4 polyamines, 4 nucleic acids, and 16 compounds from other chemical classes (Table S1). We selected biologically-relevant biomarker candidates based on a three step approach: (1) their expression profile in stand- ardized bees and its relation with viral presence, (2) pathways analysis on significant me- tabolites; and (3) a literature search to identify potential viral specific signatures. Step (1) and (2), pathways analysis on significant metabolites We performed two-way ANOVA with Tukey HSD tests for post-hoc comparisons and used significant metabolites for metabolic pathway analysis using the web-based Citation: Wang, L.L.; Van platform MetaboAnalyst (http://www.metaboanalyst.ca/) in order to get insights in the Meulebroek, L.; Vanhaecke. -

Syntrophic Butyrate and Propionate Oxidation Processes 491

Environmental Microbiology Reports (2010) 2(4), 489–499 doi:10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00147.x Minireview Syntrophic butyrate and propionate oxidation processes: from genomes to reaction mechanismsemi4_147 489..499 Nicolai Müller,1† Petra Worm,2† Bernhard Schink,1* a cytoplasmic fumarate reductase to drive energy- Alfons J. M. Stams2 and Caroline M. Plugge2 dependent succinate oxidation. Furthermore, we 1Faculty for Biology, University of Konstanz, D-78457 propose that homologues of the Thermotoga mar- Konstanz, Germany. itima bifurcating [FeFe]-hydrogenase are involved 2Laboratory of Microbiology, Wageningen University, in NADH oxidation by S. wolfei and S. fumaroxidans Dreijenplein 10, 6703 HB Wageningen, the Netherlands. to form hydrogen. Summary Introduction In anoxic environments such as swamps, rice fields In anoxic environments such as swamps, rice paddy fields and sludge digestors, syntrophic microbial communi- and intestines of higher animals, methanogenic commu- ties are important for decomposition of organic nities are important for decomposition of organic matter to matter to CO2 and CH4. The most difficult step is the CO2 and CH4 (Schink and Stams, 2006; Mcinerney et al., fermentative degradation of short-chain fatty acids 2008; Stams and Plugge, 2009). Moreover, they are the such as propionate and butyrate. Conversion of these key biocatalysts in anaerobic bioreactors that are used metabolites to acetate, CO2, formate and hydrogen is worldwide to treat industrial wastewaters and solid endergonic under standard conditions and occurs wastes. Different types of anaerobes have specified only if methanogens keep the concentrations of these metabolic functions in the degradation pathway and intermediate products low. Butyrate and propionate depend on metabolite transfer which is called syntrophy degradation pathways include oxidation steps of (Schink and Stams, 2006). -

Dietary Supplementation of Inorganic, Organic, and Fatty Acids in Pig: a Review

animals Review Dietary Supplementation of Inorganic, Organic, and Fatty Acids in Pig: A Review Giulia Ferronato * and Aldo Prandini Department of Animal Sciences, Food and Nutrition (DIANA), Faculty of Agriculture, Food and Environmental Science, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Via Emilia Parmense 84, 29100 Piacenza, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 14 August 2020; Accepted: 18 September 2020; Published: 25 September 2020 Simple Summary: The role of acids in pig feed strategies has changed from feed acidifier and preservative to growth promoter and antibiotics substitute. Since the 2006 European banning of growth promoters in the livestock sector, several feed additives have been tested with the goal of identifying molecules with the greatest beneficial antimicrobial, growth-enhancing, or disease-preventing abilities. These properties have been identified among various acids, ranging from inexpensive inorganic acids to organic and fatty acids, and these have been widely used in pig production. Acids are mainly used during the weaning period, which is considered one of the most critical phases in pig farming, as well as during gestation, lactation, and fattening. Such supplementation generally yields improved growth performance and increased feed efficiency; these effects are the consequences of different modes of action acting on the microbiome composition, gut mucosa morphology, enzyme activity, and animal energy metabolism. Abstract: Reduction of antibiotic use has been a hot topic of research over the past decades. The European ban on growth-promoter use has increased the use of feed additivities that can enhance animal growth performance and health status, particularly during critical and stressful phases of life. -

Manipulating Posttranslational Modification in Natural Product Biosynthesis

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Manipulating posttranslational modification in natural product biosynthesis Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0sn8v44w Author Foley, Timothy Leyden Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Manipulating Posttranslational Modification in Natural Product Biosynthesis A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chemistry by Timothy Leyden Foley Committee in charge: Professor Michael D. Burkart, Chair Professor Stuart Brody Professor Elizabeth A. Komives Professor Emmanuel Theodorakis Professor Jerry Yang 2010 Copyright Timothy Leyden Foley, 2010 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Timothy Leyden Foley is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my family and friends. Most of all, to my mother, whose constant support and unwaivering acceptance of my decisions has been -

Phenotype Microarrays™

Phenotype MicroArrays™ PM1 MicroPlate™ Carbon Sources A1 A2 A3 A4 A5 A6 A7 A8 A9 A10 A11 A12 Negative Control L-Arabinose N-Acetyl -D- D-Saccharic Acid Succinic Acid D-Galactose L-Aspartic Acid L-Proline D-Alanine D-Trehalose D-Mannose Dulcitol Glucosamine B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B7 B8 B9 B10 B11 B12 D-Serine D-Sorbitol Glycerol L-Fucose D-Glucuronic D-Gluconic Acid D,L -α-Glycerol- D-Xylose L-Lactic Acid Formic Acid D-Mannitol L-Glutamic Acid Acid Phosphate C1 C2 C3 C4 C5 C6 C7 C8 C9 C10 C11 C12 D-Glucose-6- D-Galactonic D,L-Malic Acid D-Ribose Tween 20 L-Rhamnose D-Fructose Acetic Acid -D-Glucose Maltose D-Melibiose Thymidine α Phosphate Acid- -Lactone γ D-1 D2 D3 D4 D5 D6 D7 D8 D9 D10 D11 D12 L-Asparagine D-Aspartic Acid D-Glucosaminic 1,2-Propanediol Tween 40 -Keto-Glutaric -Keto-Butyric -Methyl-D- -D-Lactose Lactulose Sucrose Uridine α α α α Acid Acid Acid Galactoside E1 E2 E3 E4 E5 E6 E7 E8 E9 E10 E11 E12 L-Glutamine m-Tartaric Acid D-Glucose-1- D-Fructose-6- Tween 80 -Hydroxy -Hydroxy -Methyl-D- Adonitol Maltotriose 2-Deoxy Adenosine α α ß Phosphate Phosphate Glutaric Acid- Butyric Acid Glucoside Adenosine γ- Lactone F1 F2 F3 F4 F5 F6 F7 F8 F9 F10 F11 F12 Glycyl -L-Aspartic Citric Acid myo-Inositol D-Threonine Fumaric Acid Bromo Succinic Propionic Acid Mucic Acid Glycolic Acid Glyoxylic Acid D-Cellobiose Inosine Acid Acid G1 G2 G3 G4 G5 G6 G7 G8 G9 G10 G11 G12 Glycyl-L- Tricarballylic L-Serine L-Threonine L-Alanine L-Alanyl-Glycine Acetoacetic Acid N-Acetyl- -D- Mono Methyl Methyl Pyruvate D-Malic Acid L-Malic Acid ß Glutamic Acid Acid -

Omega-3 Fatty Acids Correlate with Gut Microbiome Diversity And

Omega-3 fatty acids correlate with gut microbiome diversity and production of N- carbamylglutamate in middle aged and elderly women Cristina Mennia, Jonas Zierera, Tess Pallistera, Matthew A Jacksona, Tao Longb, Robert P Mohneyc, Claire J Stevesa, Tim D Spectora, Ana M Valdesa,d,e a Department of Twin Research and Genetic Epidemiology, Kings College London, London, UK. b Sanford Burnham Prebys, USA cMetabolon Inc., Raleigh-Durham, NC 27709, USA. dSchool of Medicine , Nottingham City Hospital, Hucknall Road, Nottingham, UK. e NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre, Nottingham, UK. Corresponding author: Dr Ana M Valdes School of Medicine Clinical Sciences Building, Nottingham City Hospital, Hucknall Road, Nottingham, NG5 1PB, UK Phone number: +44 (0)115 823 1954; Fax number:+44(0) 115 823 1757 email: [email protected] Supplementary Table 1. List of faecal metabolites significantly associated to DHA circulating levels (FDR<0.05)adjusting for age, BMI and family relatedness. Super Pathway Sub pathway Metabolite BETA SE P Q Lipid Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid (n3 and n6) eicosapentaenoate (EPA; 20:5n3) 0.15 0.04 4.35x10-5 0.01 Xenobiotics Carbamylated aminoacid N-carbamylglutamate 0.15 0.04 1.21x10-4 0.02 Peptide Dipeptide Derivative anserine 0.13 0.04 5.39x10-4 0.04 Supplementary Table 2. Associations between five measures of microbiome diversity and circulating levels of PUFA adjusting for age, BMI fibre intake and family relatedness SHANNON DIVERSITY CHAO1 OBSERVED Phylogenetic Diversity SIMPSON SPECIES Beta SE P Beta SE P Beta SE P Beta SE P Beta SE P DHA 0.13 0.04 0.002 0.12 0.04 0.003 0.14 0.04 0.001 0.12 0.04 0.01 0.09 0.04 0.02 FAW3 0.12 0.04 0.005 0.13 0.04 0.003 0.13 0.04 0.002 0.12 0.05 0.01 0.08 0.04 0.05 LA 0.10 0.05 0.02 0.10 0.05 0.03 0.10 0.05 0.03 0.10 0.05 0.03 0.09 0.04 0.04 (18:2) FAW6 0.09 0.04 0.02 0.10 0.04 0.01 0.10 0.04 0.01 0.10 0.04 0.02 0.08 0.04 0.05 DHA=22:6 docosahexaenoic acid;, FAW3= Omega-3 fatty acids; 18:2, LA= linoleic acid;; FAW6=omega-6 fatty acids Supplementary Table 3. -

Formation of Cadaverine As an Effect of A-Difluoromethylornithine on Chick Embryo Fibroblasts Transformed by Rous Sarcoma Virus

(CANCER RESEARCH 45, 2159-2164, May 1985] Formation of Cadaverine as an Effect of a-Difluoromethylornithine on Chick Embryo Fibroblasts Transformed by Rous Sarcoma Virus Uriel Bachrach and Alalia Shtorch Department of Molecular Biology, Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School, Jerusalem, Israel ABSTRACT that DFMO does not interfere with the growth, DNA synthesis, and protein synthesis of normal and transformed cells. However, Chick embryo fibre-blasts grew normally in the presence of 1 DFMO leads to a significant reduction of cellular putrescine x 10~3 to 10 x 1CT3 M a-difluoromethylornithine (DFMO). This levels. This decrease is compensated by the accumulation of drug did not interfere with protein and DNA synthesis of normal cadaverine (1,5-diaminopentane) in the DFMO-treated cells. A fibroblasts and of cells transformed by Rous sarcoma virus. The preliminary account of this work has been given previously (5). morphological appearance of normal and transformed cells was not altered by DFMO, as determined by scanning electron mi croscopy. Flow microfluorometric analyses also confirmed the MATERIALS AND METHODS notion that normal or transformed cells were not blocked by Viruses and Tissue Cultures. A wild type of RSV-SR 17-A and its DFMO in the Gìphase of the cell cycle. As expected, DFMO temperature-sensitive mutant, T5, were used as described elsewhere reduced cellular putrescine levels. This diamine, however, was (10,11). Primary cultures of CEF, prepared from 9- to 11-day-old chick replaced by the analogue cadaverine (1,5-diaminopentane), embryos, were seeded on 90-mm plastic plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Den which accumulated mainly in the transformed cells. -

Biotechnology for Biofuels

Biotechnology for Biofuels This Provisional PDF corresponds to the article as it appeared upon acceptance. Fully formatted PDF and full text (HTML) versions will be made available soon. Comparative metagenomics of biogas-producing microbial communities from production-scale biogas plants operating under wet or dry fermentation conditions Biotechnology for Biofuels (2015)8:14Sample doi:10.1186/s13068-014-0193-8 Yvonne Stolze ([email protected]) Martha Zakrzewski ([email protected]) Irena Maus ([email protected]) Felix Eikmeyer ([email protected]) Sebastian Jaenicke ([email protected]) Nils Rottmann ([email protected]) Clemens Siebner ([email protected]) Alfred Pühler ([email protected]) Andreas Schlüter ([email protected]) Sample ISSN 1754-6834 Article type Research article Submission date 29 September 2014 Acceptance date 22 December 2014 Article URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13068-014-0193-8 Like all articles in BMC journals, this peer-reviewed article can be downloaded, printed and distributed freely for any purposes (see copyright notice below). Articles in BMC journals are listed in PubMed and archived at PubMed Central. For information about publishing your research in BMC journals or any BioMed Central journal, go to http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/authors/ © 2015 Stolze et al.; licensee BioMed Central. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. -

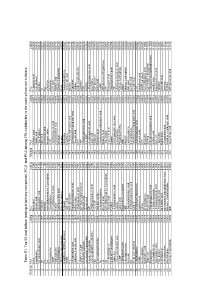

Table S1. to P 50 and Bo Ttom Loadin G of Primary Com Pone Nt

Table S1. Top 50 and bottom loading of primary component (PC)1 and PC2 among 276 metabolites in the roots of two rice cultivars. Ranking PC1 Loding PC2 Loding Ranking PC1 Loding PC2 Loding 1 β-Ala 0.1133 Mucic acid 0.1344 227 Sebacic acid -0.0017 Pelargonic acid -0.0668 2 Hypotaurine 0.1127 Glucaric acid 0.1247 228 Vanillic acid -0.0020 CoA_divalent -0.0672 3 3-Aminoisobutyric acid 0.1116 Glucosaminic acid 0.1192 229 Trimethylamine -0.0021 Ornithine -0.0676 4 Thr 0.1097 Pyridoxine 0.1180 230 Malic acid -0.0029 Tyr -0.0677 5 Pro 0.1075 Allantoin 0.1158 231 cis-Aconitic acid -0.0030 Arg -0.0680 6 Ser 0.1062 N-Acetylglucosamine 1-phosphate 0.1090 232 Norspermidine -0.0033 γ-Glu-Cys -0.0685 7 O-Acetylserine 0.1051 Trimethylamine 0.1039 233 GMP -0.0038 Adenosine -0.0699 8 cGMP 0.1050 Trimethylamine N-oxide 0.1036 234 2-Hydroxyvaleric acid -0.0044 Citric acid -0.0703 9 Hydroxyproline 0.1032 Betaine 0.1016 235 2-Oxoisovaleric acid -0.0056 Allantoic acid -0.0716 10 N6-Methyllysine 0.1029 Cysteinesulfinic acid 0.1009 236 Uric acid -0.0056 Glucose 6-phosphate -0.0718 11 CMP-N-acetylneuraminate 0.1029 N-Acetyl-β-alanine 0.0991 237 Adenine -0.0071 Rhein -0.0757 12 Glutathione (GSSG)_divalent 0.1020 Pyridoxal 0.0981 238 Adenosine -0.0079 Homoserinelactone -0.0761 13 SDMA 0.1014 Vanillic acid 0.0980 239 Morpholine -0.0082 cis-Aconitic acid -0.0772 14 Phe 0.1014 N-Acetylcysteine 0.0961 240 11-Aminoundecanoic acid -0.0108 Adenine -0.0774 15 5-Aminovaleric acid 0.1014 Phosphoenolpyruvic acid 0.0952 241 1H-Imidazole-4-propionic acid -0.0113 Guanosine -0.0776