Wild Chimpanzees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan Paniscus)

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Editors: Dr Jeroen Stevens Contact information: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp – K. Astridplein 26 – B 2018 Antwerp, Belgium Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Great Ape TAG TAG Chair: Dr. María Teresa Abelló Poveda – Barcelona Zoo [email protected] Edition: First edition - 2020 1 2 EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (February 2020) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA APE TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

§4-71-6.5 LIST of CONDITIONALLY APPROVED ANIMALS November

§4-71-6.5 LIST OF CONDITIONALLY APPROVED ANIMALS November 28, 2006 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Plesiopora FAMILY Tubificidae Tubifex (all species in genus) worm, tubifex PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Crustacea ORDER Anostraca FAMILY Artemiidae Artemia (all species in genus) shrimp, brine ORDER Cladocera FAMILY Daphnidae Daphnia (all species in genus) flea, water ORDER Decapoda FAMILY Atelecyclidae Erimacrus isenbeckii crab, horsehair FAMILY Cancridae Cancer antennarius crab, California rock Cancer anthonyi crab, yellowstone Cancer borealis crab, Jonah Cancer magister crab, dungeness Cancer productus crab, rock (red) FAMILY Geryonidae Geryon affinis crab, golden FAMILY Lithodidae Paralithodes camtschatica crab, Alaskan king FAMILY Majidae Chionocetes bairdi crab, snow Chionocetes opilio crab, snow 1 CONDITIONAL ANIMAL LIST §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Chionocetes tanneri crab, snow FAMILY Nephropidae Homarus (all species in genus) lobster, true FAMILY Palaemonidae Macrobrachium lar shrimp, freshwater Macrobrachium rosenbergi prawn, giant long-legged FAMILY Palinuridae Jasus (all species in genus) crayfish, saltwater; lobster Panulirus argus lobster, Atlantic spiny Panulirus longipes femoristriga crayfish, saltwater Panulirus pencillatus lobster, spiny FAMILY Portunidae Callinectes sapidus crab, blue Scylla serrata crab, Samoan; serrate, swimming FAMILY Raninidae Ranina ranina crab, spanner; red frog, Hawaiian CLASS Insecta ORDER Coleoptera FAMILY Tenebrionidae Tenebrio molitor mealworm, -

Gorilla Beringei (Eastern Gorilla) 07/09/2016, 02:26

Gorilla beringei (Eastern Gorilla) 07/09/2016, 02:26 Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia ChordataMammaliaPrimatesHominidae Scientific Gorilla beringei Name: Species Matschie, 1903 Authority: Infra- specific See Gorilla beringei ssp. beringei Taxa See Gorilla beringei ssp. graueri Assessed: Common Name(s): English –Eastern Gorilla French –Gorille de l'Est Spanish–Gorilla Oriental TaxonomicMittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B. and Wilson D.E. 2013. Handbook of the Mammals of the World: Volume Source(s): 3 Primates. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. This species appeared in the 1996 Red List as a subspecies of Gorilla gorilla. Since 2001, the Eastern Taxonomic Gorilla has been considered a separate species (Gorilla beringei) with two subspecies: Grauer’s Gorilla Notes: (Gorilla beringei graueri) and the Mountain Gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei) following Groves (2001). Assessment Information [top] Red List Category & Criteria: Critically Endangered A4bcd ver 3.1 Year Published: 2016 Date Assessed: 2016-04-01 Assessor(s): Plumptre, A., Robbins, M. & Williamson, E.A. Reviewer(s): Mittermeier, R.A. & Rylands, A.B. Contributor(s): Butynski, T.M. & Gray, M. Justification: Eastern Gorillas (Gorilla beringei) live in the mountainous forests of eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, northwest Rwanda and southwest Uganda. This region was the epicentre of Africa's "world war", to which Gorillas have also fallen victim. The Mountain Gorilla subspecies (Gorilla beringei beringei), has been listed as Critically Endangered since 1996. Although a drastic reduction of the Grauer’s Gorilla subspecies (Gorilla beringei graueri), has long been suspected, quantitative evidence of the decline has been lacking (Robbins and Williamson 2008). During the past 20 years, Grauer’s Gorillas have been severely affected by human activities, most notably poaching for bushmeat associated with artisanal mining camps and for commercial trade (Plumptre et al. -

Bonobos (Pan Paniscus) Show an Attentional Bias Toward Conspecifics’ Emotions

Bonobos (Pan paniscus) show an attentional bias toward conspecifics’ emotions Mariska E. Kreta,1, Linda Jaasmab, Thomas Biondac, and Jasper G. Wijnend aInstitute of Psychology, Cognitive Psychology Unit, Leiden University, 2333 AK Leiden, The Netherlands; bLeiden Institute for Brain and Cognition, 2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands; cApenheul Primate Park, 7313 HK Apeldoorn, The Netherlands; and dPsychology Department, University of Amsterdam, 1018 XA Amsterdam, The Netherlands Edited by Susan T. Fiske, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, and approved February 2, 2016 (received for review November 8, 2015) In social animals, the fast detection of group members’ emotional perspective, it is most adaptive to be able to quickly attend to rel- expressions promotes swift and adequate responses, which is cru- evant stimuli, whether those are threats in the environment or an cial for the maintenance of social bonds and ultimately for group affiliative signal from an individual who could provide support and survival. The dot-probe task is a well-established paradigm in psy- care (24, 25). chology, measuring emotional attention through reaction times. Most primates spend their lives in social groups. To prevent Humans tend to be biased toward emotional images, especially conflicts, they keep close track of others’ behaviors, emotions, and when the emotion is of a threatening nature. Bonobos have rich, social debts. For example, chimpanzees remember who groomed social emotional lives and are known for their soft and friendly char- whom for long periods of time (26). In the chimpanzee, but also in acter. In the present study, we investigated (i) whether bonobos, the rarely studied bonobo, grooming is a major social activity and similar to humans, have an attentional bias toward emotional scenes a means by which animals living in proximity may bond and re- ii compared with conspecifics showing a neutral expression, and ( ) inforce social structures. -

Orangutan…Taxonomy…And…Nomenclature

«««« ORANGUTAN…TAXONOMY…AND…NOMENCLATURE« « Craig«D em itros« « The«taxonom y«of«the«orangutan«has«been«confusing«and«is«still«the«subject«of« m uch«debate.«Q uestions«at«the«specific«and«subspecific«level«are«still«being« investigated«(Courtenay«et«al.«1988).«The«follow ing«taxonom ic«inform ation«is« taken«prim arily«from «G roves,«1971.« « H IG H ER«LEVEL«TAXO N O M Y:« O rder:«Prim ates« Suborder:«A nthropoidea« Superfam ily:«H om inoidea« Fam ily:«Pongidae«(Includes«extant«genera«Pan,…Gorilla…and…Pongo).« « H ISTO RICA L«TAXO N O M Y«AT«TH E«G EN U S«A N D «G EN U S«SPECIES«LEVEL:«« G enus« Pongo«Lacepede,«1799.« O urangus«Zim m erm an,«1777«(N am e«invalidated).« « G enus«species«(Pongo…pygm aeus«H oppius,«1763).« Sim ia…pygm aeus«H oppius,«1763.««Type«locality«Sum atra.« Sim ia…satyrus«Linnaeus,«1766.« O urangus…outangus«Zim m erm an,«1777.« Pongo…borneo«Lacepede,«1799.««Type«locality«Borneo.« Sim ia…Agrais«Schreber,«1779.««Type«locality«Borneo.« Pongo…W urm bii«Tiedem ann,«1808.««Type«locality«Borneo.« Pongo…Abelii«Lesson,«1827.««Type«locality«Sum atra.« Sim ia…M orio«O w en,«1836.««Type«locality«Borneo.« Pithecus…bicolor«I.«G eoffroy,«1841.««Type«locality«Sum atra.« Sim ia…Gargantica«Pearson,«1841.««Type«locality«Sum atra.« Pithecus…brookei«Blyth,«1853.««Type«locality«Saraw ak.« Pithecus…ow enii«Blyth,«1853.««Type«locality«Saraw ak.« Pithecus…curtus«Blyth,«1855.««Type«locality«Saraw ak.« Satyrus…Knekias«M eyer,«1856.««Type«locality«Borneo.« Pithecus…W allichii«G ray,«1870.««Type«locality«Borneo.« Pithecus…sum atranus«Selenka,«1896.««Type«locality«Sum atra.« Pongo…pygm aeus«Rothschild,«1904.««First«use«of«this«com bination.« Ptihecus…w allacei«Elliot,«1913.««Type«locality«Borneo.« « CURRENT…TAXONOMY« « The«current«and«m ost«accepted«taxonom y«of«the«G enus«Pongo«includes«one« species«Pongo…pygm aeus«and«tw o«subspecies«P.p.…pygm aeus«(the«Bornean« subspecies)«and«P.p.…abelii«(the«Sum atran«subspecies)«(Bem m el«1968;«Jones« 1969;«G roves«1971;«Jacobshagen«1979;«Seuarez«et«al.«1979«and«G roves«1993).« 5« « . -

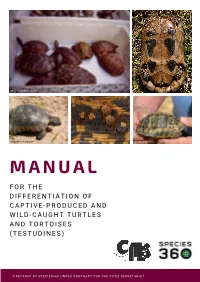

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

University of Nevada, Reno Effects of Fire on Desert Tortoise (Gopherus Agassizii) Thermal Ecology a Dissertation Submitted in P

University of Nevada, Reno Effects of fire on desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) thermal ecology A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology by Sarah J. Snyder Dr. C. Richard Tracy/Dissertation Advisor May 2014 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by SARAH J. SNYDER Entitled Effects of fire on desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) thermal ecology be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY C. Richard Tracy, Ph.D., Advisor Kenneth Nussear, Ph.D., Committee Member Peter Weisberg, Ph.D., Committee Member Lynn Zimmerman, Ph.D., Committee Member Lesley DeFalco, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph. D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2014 i ABSTRACT Among the many threats facing the desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) is the destruction and alteration of habitat. In recent years, wildfires have burned extensive portions of tortoise habitat in the Mojave Desert, leaving burned landscapes that are virtually devoid of living vegetation. Here, we investigated the effects of fire on the thermal ecology of the desert tortoise by quantifying the thermal quality of above- and below-ground habitat, determining which shrub species are most thermally valuable for tortoises including which shrub species are used by tortoises most frequently, and comparing the body temperature of tortoises in burned and unburned habitat. To address these questions we placed operative temperature models in microhabitats that received filtered radiation to test the validity of assuming that the interaction between radiation and radiation-absorbing properties of the model can result in a single, mean radiant absorptance regardless of whether the incident solar radiation is direct unfiltered or filtered by plant canopies, using the desert tortoise as a case study. -

Download Vol. 20, No. 2

BULLETIN of the FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM Biological Sciences Volume 20 1976 Number 2 THE GENUS GOPHERUS ( TESTUDINIDAE ): PT. I. OSTEOLOGY AND RELATIONSHIPS OF EXTANT SPECIES WALTER AUFFENBERC e = UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA GAINESVILLE Numbers of the BULLETIN OF THE FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM, BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES, are published at irregular intervals. Volumes contain about 300 pages and are not necessaril; completed in any one calendar year. CARTER R. GILBERT, Editor RHODA J, RYBAK, Managing Editor Consultants for this issue: JAMES L. DOBIE J, ALAN HOLMAN SAM R. TELFORD, JR. Communications concerning purchase or exchange of the publications and all man- uscripts should be addressed to the Managing Editor of the Bulletin, Florida State Museum, Museum Road, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611. This public document was promulgated at an annual cost of $2,561.67 or $2.328 per copy. It makes available to libraries, scholars, and all interested persons the results of researches in the natural sciences, emphasizing the Circum-Caribbean region. Publication date: January 23, 1976 Price $2.35 THE GENUS GOPHERUS (TESTUDINIDAE): PT. I. OSTEOLOGY AND RELATIONSHIPS OF EXTANT SPECIES WALTER AUFFENBERGl SYNOPSIS: Adult skeletons of the extant species of the genus Gopherus were studied to determine the kind and level of similarities and differences between them and to form a comparative base for studies of fossil members of the genus. The skeleton and its variation in each of the species is described and/or figured and analyzed. The four extant species form two species groups, based on a number of osteological characters. One group includes G. polyphemus and G, #avomarginatus, the other G. -

Movement, Home Range and Habitat Use in Leopard Tortoises (Stigmochelys Pardalis) on Commercial

Movement, home range and habitat use in leopard tortoises (Stigmochelys pardalis) on commercial farmland in the semi-arid Karoo. Martyn Drabik-Hamshare Submitted in fulfilment of the academic requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Discipline of Ecological Sciences School of Life Sciences College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science University of KwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg Campus 2016 ii ABSTRACT Given the ever-increasing demand for resources due to an increasing human population, vast ranges of natural areas have undergone land use change, either due to urbanisation or production and exploitation of resources. In the semi-arid Karoo of southern Africa, natural lands have been converted to private commercial farmland, reducing habitat available for wildlife. Furthermore, conversion of land to energy production is increasing, with areas affected by the introduction of wind energy, solar energy, or hydraulic fracturing. Such widespread changes affects a wide range of animal and plant communities. Southern Africa hosts the highest diversity of tortoises (Family: Testudinidae), with up to 18 species present in sub-Saharan Africa, and 13 species within the borders of South Africa alone. Diversity culminates in the Karoo, whereby up to five species occur. Tortoises throughout the world are undergoing a crisis, with at least 80 % of the world’s species listed at ‘Vulnerable’ or above. Given the importance of many tortoise species to their environments and ecosystems— tortoises are important seed dispersers, whilst some species produce burrows used by numerous other taxa—comparatively little is known about certain aspects relating to their ecology: for example spatial ecology, habitat use and activity patterns. -

Growing and Shrinking in the Smallest Tortoise, Homopus Signatus Signatus: the Importance of Rain

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Oecologia (2007) 153:479–488 DOI 10.1007/s00442-007-0738-7 GLOBAL CHANGE AND CONSERVATION ECOLOGY Growing and shrinking in the smallest tortoise, Homopus signatus signatus: the importance of rain Victor J. T. Loehr · Margaretha D. Hofmeyr · Brian T. Henen Received: 21 November 2006 / Accepted: 21 March 2007 / Published online: 24 April 2007 © Springer-Verlag 2007 Abstract Climate change models predict that the range of dorso-ventrally, so a reduction in internal matter due to the world’s smallest tortoise, Homopus signatus signatus, starvation or dehydration may have caused SH to shrink. will aridify and contract in the next decades. To evaluate Because the length and width of the shell seem more rigid, the eVects of annual variation in rainfall on the growth of reversible bone resorption may have contributed to shrink- H. s. signatus, we recorded annual growth rates of wild age, particularly of the shell width and plastron length. individuals from spring 2000 to spring 2004. Juveniles Based on growth rates for all years, female H. s. signatus grew faster than did adults, and females grew faster than need 11–12 years to mature, approximately twice as long as did males. Growth correlated strongly with the amount of would be expected allometrically for such a small species. rain that fell during the time just before and within the However, if aridiWcation lowers average growth rates to the growth periods. Growth rates were lowest in 2002–2003, level of 2002–2003, females would require 30 years to when almost no rain fell between September 2002 and mature. -

Conservation of South African Tortoises with Emphasis on Their Apicomplexan Haematozoans, As Well As Biological and Metal-Fingerprinting of Captive Individuals

CONSERVATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN TORTOISES WITH EMPHASIS ON THEIR APICOMPLEXAN HAEMATOZOANS, AS WELL AS BIOLOGICAL AND METAL-FINGERPRINTING OF CAPTIVE INDIVIDUALS By Courtney Antonia Cook THESIS submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (Ph.D.) in ZOOLOGY in the FACULTY OF SCIENCE at the UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG Supervisor: Prof. N. J. Smit Co-supervisors: Prof. A. J. Davies and Prof. V. Wepener June 2012 “We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals. Remote from universal nature, and living by complicated artifice, man in civilization surveys the creature through the glass of his knowledge and sees thereby a feather magnified and the whole image in distortion. We patronize them for their incompleteness, for their tragic fate of having taken form so far below ourselves. And therein we err, and greatly err. For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours they move finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings; they are other nations caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth.” Henry Beston (1928) ABSTRACT South Africa has the highest biodiversity of tortoises in the world with possibly an equivalent diversity of apicomplexan haematozoans, which to date have not been adequately researched. Prior to this study, five apicomplexans had been recorded infecting southern African tortoises, including two haemogregarines, Haemogregarina fitzsimonsi and Haemogregarina parvula, and three haemoproteids, Haemoproteus testudinalis, Haemoproteus balazuci and Haemoproteus sp.