Physics at CERN's Antiproton Decelerator Arxiv:1304.3721V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CERN Courier–Digital Edition

CERNMarch/April 2021 cerncourier.com COURIERReporting on international high-energy physics WELCOME CERN Courier – digital edition Welcome to the digital edition of the March/April 2021 issue of CERN Courier. Hadron colliders have contributed to a golden era of discovery in high-energy physics, hosting experiments that have enabled physicists to unearth the cornerstones of the Standard Model. This success story began 50 years ago with CERN’s Intersecting Storage Rings (featured on the cover of this issue) and culminated in the Large Hadron Collider (p38) – which has spawned thousands of papers in its first 10 years of operations alone (p47). It also bodes well for a potential future circular collider at CERN operating at a centre-of-mass energy of at least 100 TeV, a feasibility study for which is now in full swing. Even hadron colliders have their limits, however. To explore possible new physics at the highest energy scales, physicists are mounting a series of experiments to search for very weakly interacting “slim” particles that arise from extensions in the Standard Model (p25). Also celebrating a golden anniversary this year is the Institute for Nuclear Research in Moscow (p33), while, elsewhere in this issue: quantum sensors HADRON COLLIDERS target gravitational waves (p10); X-rays go behind the scenes of supernova 50 years of discovery 1987A (p12); a high-performance computing collaboration forms to handle the big-physics data onslaught (p22); Steven Weinberg talks about his latest work (p51); and much more. To sign up to the new-issue alert, please visit: http://comms.iop.org/k/iop/cerncourier To subscribe to the magazine, please visit: https://cerncourier.com/p/about-cern-courier EDITOR: MATTHEW CHALMERS, CERN DIGITAL EDITION CREATED BY IOP PUBLISHING ATLAS spots rare Higgs decay Weinberg on effective field theory Hunting for WISPs CCMarApr21_Cover_v1.indd 1 12/02/2021 09:24 CERNCOURIER www. -

Few Electron Paramagnetic Resonances Detection On

FEW ELECTRON PARAMAGNETIC RESONANCES DETECTION TECHNIQUES ON THE RUBY SURFACE By Xiying Li Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Massood Tabib-Azar Co-Adviser: Dr. J. Adin Mann, Jr. Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY August, 2005 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of ______________________________________________________ candidate for the Ph.D. degree *. (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................. II LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................................... IV ABSTRACT............................................................................................................................................... VII CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................1 -

Interactions of Antiprotons with Atoms and Molecules

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln US Department of Energy Publications U.S. Department of Energy 1988 INTERACTIONS OF ANTIPROTONS WITH ATOMS AND MOLECULES Mitio Inokuti Argonne National Laboratory Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdoepub Part of the Bioresource and Agricultural Engineering Commons Inokuti, Mitio, "INTERACTIONS OF ANTIPROTONS WITH ATOMS AND MOLECULES" (1988). US Department of Energy Publications. 89. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdoepub/89 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Energy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in US Department of Energy Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. /'Iud Tracks Radial. Meas., Vol. 16, No. 2/3, pp. 115-123, 1989 0735-245X/89 $3.00 + 0.00 Inl. J. Radial. Appl .. Ins/rum., Part D Pergamon Press pic printed in Great Bntam INTERACTIONS OF ANTIPROTONS WITH ATOMS AND MOLECULES* Mmo INOKUTI Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, Illinois 60439, U.S.A. (Received 14 November 1988) Abstract-Antiproton beams of relatively low energies (below hundreds of MeV) have recently become available. The present article discusses the significance of those beams in the contexts of radiation physics and of atomic and molecular physics. Studies on individual collisions of antiprotons with atoms and molecules are valuable for a better understanding of collisions of protons or electrons, a subject with many applications. An antiproton is unique as' a stable, negative heavy particle without electronic structure, and it provides an excellent opportunity to study atomic collision theory. -

CERN to Seek Answers to Such Fundamental 1957, Was CERN’S First Accelerator

What is the nature of our universe? What is it ----------------------------------------- DAY 1 -------- made of? Scientists from around the world go to The 600 MeV Synchrocyclotron (SC), built in CERN to seek answers to such fundamental 1957, was CERN’s first accelerator. It provided questions using particle accelerators and pushing beams for CERN’s first experiments in particle and nuclear the limits of technology. physics. In 1964, this machine started to concentrate on nuclear physics alone, leaving particle physics to the newer During February 2019, I was given a once in a lifetime and more powerful Proton Synchrotron. opportunity to be part of The Maltese Teacher Programme at CERN, which introduced me, as one of the participants, to cutting-edge particle physics through lectures, on-site visits, exhibitions, and hands-on workshops. Why do they do all this? The main objective of these type of visits is to bring modern science into the classroom. Through this report, my purpose is to give an insight of what goes on at CERN as well as share my experience with you students, colleagues, as well as the general public. The SC became a remarkably long-lived machine. In 1967, it started supplying beams for a dedicated radioactive-ion-beam facility called ISOLDE, which still carries out research ranging from pure What does “CERN” stand for? At an nuclear physics to astrophysics and medical physics. In 1990, intergovernmental meeting of UNESCO in Paris in ISOLDE was transferred to the Proton Synchrotron Booster, and the SC closed down after 33 years of service. December 1951, the first resolution concerning the establishment of a European Council for Nuclear Research SM18 is CERN’s main facility for testing large and heavy (in French Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire) superconducting magnets at liquid helium temperatures. -

ANTIPROTON and NEUTRINO PRODUCTION ACCELERATOR TIMELINE ISSUES Dave Mcginnis August 28, 2005

ANTIPROTON AND NEUTRINO PRODUCTION ACCELERATOR TIMELINE ISSUES Dave McGinnis August 28, 2005 INTRODUCTION Most of the accelerator operating period is devoted to making antiprotons for the Collider program and accelerating protons for the NUMI program. While stacking antiprotons, the same Main Injector 120 GeV acceleration cycle is used to accelerate protons bound for the antiproton production target and protons bound for the NUMI neutrino production target. This is designated as Mixed-Mode operations. The minimum cycle time is limited by the time it takes to fill the Main Injector with two Booster batches for antiproton production and five Booster batches for neutrino production (7 x 0.067 seconds) and the Main Injector ramp rate (~ 1.5 seconds). As the antiproton stack size grows, the Accumulator stochastic cooling systems slow down which requires the cycle time to be lengthened. The lengthening of the cycle time unfortunately reduces the NUMI neutrino flux. This paper will use a simple antiproton stacking model to explore some of the tradeoffs between antiproton stacking and neutrino production. ACCUMULATOR STACKTAIL SYSTEM After the target, antiprotons are injected into the Debuncher ring where they undergo a bunch rotation and are stochastically pre-cooled for injection into the Accumulator. A fresh beam pulse injected into the Accumulator from the Debuncher is merged with previous beam pulses with the Accumulator StackTail system. This system cools and decelerates the antiprotons until the antiprotons are captured by the core cooling systems as shown in Figure 1. The antiproton flux through the Stacktail system is described by the Fokker –Plank equation ∂ψ ∂φ = − (1) ∂t ∂E where φ the flux of particles passing through the energy E and ψ is the particle density of the beam at energy E. -

Beam–Material Interactions

Beam–Material Interactions N.V. Mokhov1 and F. Cerutti2 1Fermilab, Batavia, IL 60510, USA 2CERN, Geneva, Switzerland Abstract This paper is motivated by the growing importance of better understanding of the phenomena and consequences of high-intensity energetic particle beam interactions with accelerator, generic target, and detector components. It reviews the principal physical processes of fast-particle interactions with matter, effects in materials under irradiation, materials response, related to component lifetime and performance, simulation techniques, and methods of mitigating the impact of radiation on the components and environment in challenging current and future applications. Keywords Particle physics simulation; material irradiation effects; accelerator design. 1 Introduction The next generation of medium- and high-energy accelerators for megawatt proton, electron, and heavy- ion beams moves us into a completely new domain of extreme energy deposition density up to 0.1 MJ/g and power density up to 1 TW/g in beam interactions with matter [1, 2]. The consequences of controlled and uncontrolled impacts of such high-intensity beams on components of accelerators, beamlines, target stations, beam collimators and absorbers, detectors, shielding, and the environment can range from minor to catastrophic. Challenges also arise from the increasing complexity of accelerators and experimental set-ups, as well as from design, engineering, and performance constraints. All these factors put unprecedented requirements on the accuracy of particle production predictions, the capability and reliability of the codes used in planning new accelerator facilities and experiments, the design of machine, target, and collimation systems, new materials and technologies, detectors, and radiation shielding and the minimization of radiation impact on the environment. -

Event Recorded by ATLAS When the LHC's Beam 2 Reached Closed

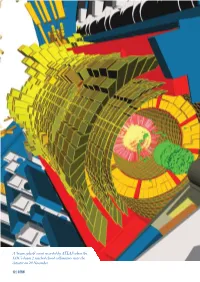

A ‘beam splash’ event recorded by ATLAS when the LHC’s beam 2 reached closed collimators near the detector on 20 November. 12 | CERN “The imminent start-up of the LHC is an event that excites everyone who has an interest in the fundamental physics of the Universe.” Kaname Ikeda, ITER Director-General, CERN Bulletin, 19 October 2009. Physics and Experiments The moment that particle physicists around the world had been The EMCal is an upgrade for ALICE, having received full waiting for finally arrived on 20 November 2009 when protons approval and construction funds only in early 2008. It will detect circulated again round the LHC. Over the following days, the high-energy photons and neutral pions, as well as the neutral machine passed a number of milestones, from the first collisions component of ‘jets’ of particles as they emerge from quark� at 450 GeV per beam to collisions at a total energy of 2.36 TeV gluon plasma formed in collisions between heavy ions; most — a world record. At the same time, the LHC experiments importantly, it will provide the means to select these events on began to collect data, allowing the collaborations to calibrate line. The EMCal is basically a matrix of scintillator and lead, detectors and assess their performance prior to the real attack which is contained in ‘supermodules’ that weigh about eight tonnes. It will consist of ten full supermodules and two partial on high-energy physics in 2010. supermodules. The repairs to the LHC and subsequent consolidation work For the ATLAS Collaboration, crucial repair work included following the incident in September 2008 took approximately modifications to the cooling system for the inner detector. -

B1.4 Microwave and Terahertz Spectroscopy

Microwave and terahertz pectroscopy 1063 B1.4 Microwave and terahertz spectroscopy Geoffrey A Blake 8 1.4.1 Introduction Spectroscopy, or the study of the interaction of light with matter. has become one of the major tools of the natural and physical ciences during this century. As the wavelength of the radiation is varied across the electromagnetic spectrum, characteristic properties of atoms, molecule , liquid and solids are probed. In the optical and ultraviolet regions (A. ""' I J-Lm up to 100 nm) it is the electronic structure of the material that is investigated, while at infrared wavelengths (""' 1-30 J-Lm) the vibrational degrees of freedom dominate. Microwave spectroscopy began in 1934 with the observation of the "-'20 GHz absorption spectrum of ammonia by Cleeton and Williams. Here we will consider the mjcrowave region of the electromagnetic spectrum to cover the l to I 00 x I 09 Hz, or I to I 00 GHz (A. ""' 30 em down to 3 mm). range. While the ammonia mjcrowave spectrum probes the inversion motion of this unique pyramidal molecule, more typically microwave spectroscopy is associated with the pure rotational motion of gas phase species. The section of the electromagnetic spectrum extending roughly from 0.1 to I 0 x 10 12 Hz (0.1-1 0 THz, 3- 300 cm- 1) is commonly known as the far-infrared (FIR), submjllimetre or terahertz (THz) region, and therefore lies between the mjcrowave and infrared windows. Accordingly, THz spectroscopy shares both cientific and technological characteri tic with its longer- and shorter-wavelength neighbours. While rich in cientific information, the FIR or THz region of the spectrum has, until recently, been notoriously lacking in good radiation ources--earning the dubious nickname 'the gap in the electromagnetic spectrum'. -

Antiproton–Proton Scattering Experiments with Polarization ( Collaboration) PAX Abstract

Technical Proposal for Antiproton–Proton Scattering Experiments with Polarization ( Collaboration) PAX arXiv:hep-ex/0505054v1 17 May 2005 J¨ulich, May 2005 2 Technical Proposal for PAX Frontmatter 3 Technical Proposal for Antiproton–Proton Scattering Experiments with Polarization ( Collaboration) PAX Abstract Polarized antiprotons, produced by spin filtering with an internal polarized gas target, provide access to a wealth of single– and double–spin observables, thereby opening a new window to physics uniquely accessible at the HESR. This includes a first measurement of the transversity distribution of the valence quarks in the proton, a test of the predicted opposite sign of the Sivers–function, related to the quark dis- tribution inside a transversely polarized nucleon, in Drell–Yan (DY) as compared to semi–inclusive DIS, and a first measurement of the moduli and the relative phase of the time–like electric and magnetic form factors GE,M of the proton. In polarized and unpolarized pp¯ elastic scattering, open questions like the contribution from the odd charge–symmetry Landshoff–mechanism at large t and spin–effects in the extraction | | of the forward scattering amplitude at low t can be addressed. The proposed de- | | tector consists of a large–angle apparatus optimized for the detection of DY electron pairs and a forward dipole spectrometer with excellent particle identification. The design and performance of the new components, required for the polarized antiproton program, are outlined. A low–energy Antiproton Polarizer Ring (APR) yields an antiproton beam polarization of Pp¯ = 0.3 to 0.4 after about two beam life times, which is of the order of 5–10 h. -

Perspective: Local Ferromagnetic Resonance Measurement Techniques

REVIEW OF SCIENTIFIC INSTRUMENTS 79, 040901 ͑2008͒ Perspective: Local ferromagnetic resonance measurement techniques: “Invited Review Article: Microwave spectroscopy based on scanning thermal microscopy: Resolution in the nanometer range” †Rev. Sci. Instrum. 79, 041101 „2008…‡ Nan Mo and Carl E. Patton Department of Physics, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523, USA ͑Received 17 March 2008; accepted 31 March 2008; published online 24 April 2008͒ According to Vonsovskii,1 ferromagnetic resonance original Frait/Soohoo schemes at different levels of sophisti- ͑FMR͒ was unknowingly discovered by Arkad’yev in 1911.2 cation. These approaches have never been able to achieve The standard citation for the experimental discovery of FMR spatial resolutions below about 10 m or so. is to Griffiths3 for his observation of the rather broad absorp- In 1988, a new approach to local FMR based on thermal tion profile and an “anomalous” electron paramagnetic reso- effects was introduced by Pelzl16 at Ruhr University, Bo- nance ͑EPR͒ field for in-plane magnetized electroplated fer- chum, Germany. This method has led to a highly sensitive 4,5 romagnetic films. One year later, Kittel explained the and very fine scale FMR measurement capability down to anomalous FMR fields by taking the dynamic demagnetizing 10 nm or so. This technique may be termed “scanning ther- fields into account. FMR is distinct from EPR because the mal FMR microscopy” ͑SThM͒. For the conventional near FMR field or frequency is shifted from the usual range of field local FMR methods introduced above, a single probe pure electron spin resonance values by substantial amounts plays a dual role in both the excitation and detection of the because of both static and dynamic demagnetizing field ef- magnetic response. -

CERN's Scientific Strategy

CERN’s Scientific Strategy Fabiola Gianotti ECFA HL-LHC Experiments Workshop, Aix-Les-Bains, 3/10/2016 CERN’s scientific strategy (based on ESPP): three pillars Full exploitation of the LHC: successful operation of the nominal LHC (Run 2, LS2, Run 3) construction and installation of LHC upgrades: LIU (LHC Injectors Upgrade) and HL-LHC Scientific diversity programme serving a broad community: ongoing experiments and facilities at Booster, PS, SPS and their upgrades (ELENA, HIE-ISOLDE) participation in accelerator-based neutrino projects outside Europe (presently mainly LBNF in the US) through CERN Neutrino Platform Preparation of CERN’s future: vibrant accelerator R&D programme exploiting CERN’s strengths and uniqueness (including superconducting high-field magnets, AWAKE, etc.) design studies for future accelerators: CLIC, FCC (includes HE-LHC) future opportunities of diversity programme (new): “Physics Beyond Colliders” Study Group Important milestone: update of the European Strategy for Particle Physics (ESPP): ~ 2019-2020 CERN’s scientific strategy (based on ESPP): three pillars Covered in this WS I will say ~nothing Full exploitation of the LHC: successful operation of the nominal LHC (Run 2, LS2, Run 3) construction and installation of LHC upgrades: LIU (LHC Injectors Upgrade) and HL-LHC Scientific diversity programme serving a broad community: ongoing experiments and facilities at Booster, PS, SPS and their upgrades (ELENA, HIE-ISOLDE) participation in accelerator-based neutrino projects outside Europe (presently mainly -

Precision Physics with Low-Energy Antiprotons — from Antiproton Decelerator to Flair∗

Vol. 41 (2010) ACTA PHYSICA POLONICA B No 2 PRECISION PHYSICS WITH LOW-ENERGY ANTIPROTONS — FROM ANTIPROTON DECELERATOR TO FLAIR∗ Eberhard Widmann Stefan Meyer Institute, Austrian Academy of Sciences Boltzmanngasse 3, 1090 Vienna, Austria (Received January 5, 2010) Experiments with low-energy antiprotons are currently performed at the Antiproton Decelerator of CERN. The main experiments deal with the spectroscopy of antiprotonic helium, an exotic three-body system, and the formation and spectroscopy of antihydrogen. A next generation facility FLAIR (Facility for Low-energy Antiproton Research) is planned at the FAIR facility, generating a factor 100 higher flux of stopped antiprotons and also offering continuous antiprotons beam, which will enable nuclear and particle physics type experiments. DOI:10.5506/APhysPolB.41.249 PACS numbers: 36.10.Gv, 11.30.Er, 14.20.Dh, 39.30.+w 1. Introduction The physics with low-energy antiprotons currently concentrates on pre- cision spectroscopy of antiprotonic atoms and antihydrogen. The reason for that is given by the characteristics of the only low-energy antiproton beam available currently at the Antiproton Decelerator (AD) of CERN. The AD [1,2] produces pulses of 3–5 × 107 antiprotons of 5.3 MeV kinetic energy every 90–120 second, which makes the beam only usable to be trapped in Penning traps or stopped in low-density gas targets. Two collaborations working at the AD, ATRAP [3] and ALPHA [4], have as goal to produce an- tihydrogen, the simplest atom consisting only of antimatter, from its charged constituents by trapping antiprotons and positrons in Pennning traps, to trap the resulting antihydrogen in a neutral-atom trap and to perform 1S–2S laser spectroscopy.