The Field System of an East Kent Parish (Deal)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda March 2021

GREAT MONGEHAM PARISH COUNCIL Thornton House, Thornton Lane, Eastry, Sandwich, Kent, CT13 OEU Tel: 01304 746036/07903 739792 25th February 2021 To all members of the Parish Council You are hereby summoned to attend the Ordinary Meeting of the Great Mongeham Parish Council to be held on Thursday 4th March 2021 at 7.30pm, virtually using Zoom, for the purposes of transacting the following business. Joanna Jones Clerk to the Parish Council AGENDA 1. APOLOGIES To receive apologies for non attendance at the meeting. The meeting will be adjourned so that members of the public can speak. Members of the public are welcome to attend but can only speak during the designated timeslot. Anyone wishing to attend please email [email protected] for the meeting details, providing your name and address. 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST To record declarations and reasons for interest from members relating to items on the agenda. 3. MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING a) To confirm the minutes of the Ordinary meeting of the Parish Council held on 4th February 2021. 4. ACTIONS FROM THE LAST MEETING To receive information resulting from actions generated at the last meeting. 5. CORONAVIRUS UPDATE a) Information from DDC, KCC and Central Government All emails received in connection with the Coronavirus and vaccinations have been forwarded to Council members as received. The situation changes frequently and the information is fluid in nature. NALC and SLCC continue to strongly advise local councils to continue to meet remotely, without the need for face to face contact. 6. PLANNING a) Planning Applications To discuss any planning applications received prior to the meeting. -

Black Lane (PINS Ref: ROW–3237045) BHS Comment on Objector’S Statement of Case

Black Lane (PINS ref: ROW–3237045) BHS comment on objector’s statement of case A. Introduction A.1. These are the comments on the British Horse Society (BHS) on the statement of case submitted by ET Landnet on behalf of its client, Mr Fox-Pitt. We refer below to the position represented by ET Landnet as the case made by ‘the objector’. We refer to refer- ences in the BHS statement of case as ‘SOC, X.Y’, meaning item Y in part X of the state- ment of case. We refer to the order way as ‘Black Lane’. We refer to numbered paragraphs in the objector’s statement of case as ‘ETL, para.X’. A.2. We make the following observation in opening. A.3. Firstly, we recognise, as the objector observes, that there are inconsistencies in the evidence in support of confirming the order. That is why there is an order before the Secretary of State. If Black Lane had remained in continuous and unchallenged use up to the present day, the whole of it would have been readily identified and added to the defin- itive map and statement under Part IV of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. As it is, use has been in decline since the early nineteenth century (SOC, I.G), and only part was recorded under the 1949 Act — and then only as an apparently dead- end footpath (see our comments at para.C.20 below). A.4. Secondly, the Knowlton estate was acquired in 1904 by Maj. Francis Elmer Speed,1 of whom Marietta Fox-Pitt (née Speed), the present owner of Knowlton Court, is a descendent. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

List of applications decided between 18/05/2020 and 25/05/2020 (Decision Date) REFERENCE ADDRESS PROPOSAL DECISION DATE DECISION CON/19/00838/M 45 Eythorne Road 26 - Retaining Wall 18-May-2020 CONAP Shepherdswell Kent CON/18/01334/C The Charity Inn 9 - Construction Management 18-May-2020 COAPP The Street Plan Woodnesborough Sandwich Kent CT13 0ND CON/19/01361/D Site At 12 - Foul Water 19-May-2020 COAPP Summerfield Farm Barnsole Road Staple Kent CON/18/01334/B The Charity Inn 4 - Levels 20-May-2020 COAPP The Street Woodnesborough Sandwich Kent CT13 0ND CON/19/00838/F 45 Eythorne Road 16 - Surface Water 21-May-2020 CONAP Shepherdswell Kent CON/20/00123/C 223 Telegraph 10 - Suds Former REF 21-May-2020 CONAP Road CON/19/01157/C Deal Kent CT14 9DU REFERENCE ADDRESS PROPOSAL DECISION DATE DECISION CON/15/00336/E Denne Court Farm Condition 18 - Archaeological 21-May-2020 COPART Hammill watching brief Woodnesborough CT13 0EG 20/00320 White Gables Erection of a single storey rear 19-May-2020 GTD Woodnesborough extension Lane Eastry CT13 0DT 20/00323 Carfax House Erection of a two storey side 19-May-2020 GTD The Street extension with Juliette balcony Stourmouth and balustrade, a single storey CT3 1HY rear extension and side porch (existing single storey side extension and porch to be demolished) 20/00287 Historic Panel Display of a non-illuminated 21-May-2020 GADV Wellington Parade public information noticeboard Walmer relocated from Walmer Car Park 20/00328 8 Bluebell Drive Certificate of lawfulness 21-May-2020 CLPG Aylesham (proposed) for the erection of CT3 3GX rear conservatory, garage conversion and front canopy porch 20/00331 Manor Farm Prior approval for the change 18-May-2020 ARPR Willow Woods of the agricultural building to Road 3no. -

Village Design Statement

Contents Page 1 Introduction 4 2 Topography and Origins of the Village 5 3 Character Area Assessments of the Village 7 4 Character Areas 4.1 Mongeham Road from St. Richard’s Road to Ripple Road 8 4.2 From Mongeham Road to Cherry Lane 12 4.3 Great Mongeham Conservation Area (Church Area) 15 4.4 Northbourne Road from Mongeham Church Close, Willow Road and single-track part of Northbourne Road 18 4.5 Cherry Lane and Pixwell Lane 21 4.6 St. Richard’s Road including St. Edmund’s Road and St. Francis Close 24 5 Architectural Details 26 6 Street Furniture 28 7 Leisure and Recreation 29 8 Traffic and Transport 35 9 Views around the Village 37 10 Design Principles 38 11 Statement of Community Involvement 41 12 Acknowledgements 42 Page 3 introduction A Village Design Statement is a constructive solution to the feelings The end-product, the Great Mongeham Design Statement, follows of many residents that they have no say over development within the four aims set out in the Constitution. Firstly, it offers analysis of their own community. The Statement provides local residents with the parish of Great Mongeham, the visual character of the a voice for their unique appreciation and understanding of their landscape, the settlement pattern, building and spaces, and its village and its surroundings. In doing so, it encapsulates and system of roads and paths. Secondly, from this analysis, it distils the documents existing features, and, consequently, sets out clear essence of what makes this parish unique and distinct, and provides guidelines for harmonious and congenial design in the future, based guidance as to how this can be conserved in the future. -

Purpose of Making the Said Intended Railway, and The

4971 purpose of making the said intended railway, and Kentish Coast Railway. the works connected therewith, with powers to (Registered provisionally, according to the Act of levy and take rates, tolls, and duties upon and in the 7 and 8 of Victoria, c. 110.) respect thereof, and to confer exemptions from the OTICE is hereby given, that application is payment of rates, tolls, and duties and other rights N intended to be made to Parliament in the and privileges. ensuing session, for an Act or Acts to authorize And it is further intended, by the said Act, to the construction and maintenance of a railway or enable the said company to be incorporated as railways, with all proper works, approaches, and aforesaid, to let on lease, or sell, or amalgamate conveniences connected therewith, commencing at the said intended railway, or any part thereof, and or near the town of Dover, in the county of Kent, the works connected therewith, or with any part and within the several parishes, townships, or extra- thereof, and all or any of the powers to be con- parochial places of Charlton, Hougham, Buckland, ferred by the said Act to, and with, any other Saint James Dover, Saint Mary the Virgin Dover, existing or projected railway company or compa- East Cliffe, and the liberties of Dover Castle, or some nies, and to enable such other railway company or or one of them, in the same county of Kent; and companies to purchase, or rent, or amalgamate, terminating at near to or upon Herne Bay Pier, in with, or to execute the said intended-railway, and the parish of Herne, in the same county; with a works, or any of them, or any part thereof, and to. -

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide the Diocese of Canterbury and the Archbishop of Canterbury's Peculiar Jurisdiction

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide The Diocese of Canterbury and the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Peculiar Jurisdiction 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 2 List of Parishes of the Diocese ...................................................................................... 1 3 Map of the Parishes of the Diocese of Canterbury ......................................................... 8 4 Peculiar Jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Canterbury .................................................... 8 4.1 Deanery of the Arches ........................................................................................... 9 4.2 Deanery of Croydon ............................................................................................... 9 4.3 Deanery of Shoreham .......................................................................................... 10 4.4 Deanery of Bocking.............................................................................................. 11 4.5 Deaneries of Pagham and Tarring ....................................................................... 11 4.6 Deanery of South Malling ..................................................................................... 11 4.7 Deanery of Monks Risborough ............................................................................. 12 1 Introduction Until the mid-19th century the diocese of Canterbury comprised parishes in Kent, east of the river Medway. But with the rearrangements -

Rural Roundup

Rural Roundup Picture by Rosie Bolton Issue Number 27 October 2012 The Community Magazine for Kingsdown Ringwould-w-Oxney Ripple Sutton, Ashley, Studdal & Little Mongeham Benefice Contacts The Reverend Cathy Sigrist BA Hons The Rectory, Upper Street , Kingsdown CT14 8BJ 01304 373 951 Email: [email protected] Sister Aileen CSC Well Cottage, Upper Street. Kingsdown, CT14 8BH 01304 361 601 Mobile: 07801 282 810 Email: [email protected] Reader Mr Norman Gilliland 9 Addelam Close, Deal CT14 9LT 01304 381 589 Email: [email protected] St John the Evangelist Church, Kingsdown Churchwardens Mr Bob Wiseman Sunninghill, St Monica‟s Road CT14 8AZ 01304 371 619 Ms Liz Sharp, 15B Archery Square, Walmer, Deal, Kent CT14 7JA 01304 449 459 Mobile: 07778 452 538 E-mail: [email protected] Parochial Church Council (Secretary) Mrs Valerie Drew Esperance, Upper Street, Kingsdown CT14 8DT 01304 372 615 Parochial Church Council (Treasurer) Sister. Aileen CSC Well Cottage, Upper Street, Kingsdown CT14 8BH 01304 361 601 Sunday School Mr Norman Gilliland 9 Addelam Close, Deal CT14 9LT 01304 381 589 Email: [email protected] St Nicholas Church, Ringwould Churchwardens Miss Ursula Bailey 52 James Hall Gardens, Walmer CT14 7TA 01304 360 149 Prof Jack Rowe Manor Lodge, Manor Mews, Ringwould CT14 8HT 01304 375 487 Parochial Church Council (Secretary) Mrs Lyn Dourthe 3 Manor Mews, Ringwould CT14 01304 360 097 Parochial Church Council (Treasurer) Mrs Jean Winn Chilterns, Back Street, Ringwould CT14 8HL 01034 361 -

The Lists of Saxon Churches in the Domesday Monachorum, and White Book of St

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society ( 60 ) THE LISTS OF SAXON CHURCHES IN THE DOMESDAY MONACHORUM, AND WHITE BOOK OF ST. AUGUSTINE. BY GORDON WARD, M.D., F.S.A. THE Domesday Monachorum is an ancient manuscript book preserved in the Chapter Library at Canterbury. It has recently been pubhshed in the third volume of the V.C.H. of Kent but with little editing or discussion. It commences with a list of churches and of the dues which they paid to the Archbishop at Easter. This is foUowed by a second hst from which it is seen that certain churches had others grouped under them in the manner of rural deaneries. The third hst contains only a few names and contains a statement of the dues paid " before the coming of Lord Lanfranc the Archbishop ". At the end of this last is a sentence to the effect that " what is before written " was ordained and instituted by Lanfranc. This can hardly refer to the dues before his coming (although it has actually been read in this sense) and so must apply to the first two lists. It foUows that these hsts were compiled in the time of Lanfranc (1070- 1089). But we can go further than this. The second hst includes the churches subordinate to MUton Regis and Newington by Sittingbourne. These are stated to have been given by the Conqueror to the Abbey of St. Augustine in 1070 (Reg. Regum Anglo-Norm. 35, 39). -

Pdf Download 269 Kb

KENT ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY CATALOGUE OF COLLECTIONS DEPOSITED AT CENTRE FOR KENTISH STUDIES Supplement U2396 Issued 2009 This paper has been downloaded from www.kentarchaeology.ac. The author has placed the paper on the site for download for personal or academic use. Any other use must be cleared with the author of the paper who retains the copyright. Please email [email protected] for details regarding copyright clearance. The Kent Archaeological Society (Registered Charity 223382) welcomes the submission of papers. The necessary form can be downloaded from the website at www.kentarchaeology.ac U2396 Material deposited by KAS at CKS 1981 BOX 1 Bundles of documents each wrapped in grey paper and indexed with the following numbers: 22 Copy of John Baynords will 1642; An abstract of the Sellindge Estate 23 Milton Manor Rent Roll 1631; Hundred of Milton Lay Subsidy 1. Edw.III (modern copies) 30 Various documents relating to Christ Church, Canterbury, 14th century (modern copies) 1 Extracts from the account books of Capt. John Harvey, RN, Mayor of Sandwich 1774-5; An account of the Old Rectory House at Northfleet; various fragments relating to the rendering of the River Medway navigable c. 1600 3 Returns of Church Plate, Diocese of Canterbury; copy of compact between Archbishop Boniface and Richard de Clare, Earl of Gloucester 42 Hen.III; Peckham Register Lay Patrons of Advowson (including Register (4) 52a. Burgested 1281 21 Sept. admit to Vicar John de Faversham on present Ledes Priory); Hundred of Tenham, Folkestone, Stouting, Maidstone 1 Edw.III 1327 Lay Subsidy (including Willo der Berghestede 16); complaint of Prior of Horten against Sir W. -

East Studdal Nurseries East Studdal Kent Trust for Thanet Archaeology

East Studdal Nurseries East Studdal Kent NGR TR 32600 49780 Archaeological Desk Based Assessment Trust for Thanet Archaeology Trust for Thanet Archaeology East Studdal Nurseries East Studdal Kent NGR TR 32600 49780 Archaeological Desk Based Assessment E. J. Boast February 2018 Issue 1 Checked by G. A. Moody CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Methodology 1.3 Scope of the Report 1.4 Structure of the Report 2 Planning Context 2.1 National Planning Policy Relating to Heritage 2.2 Local Planning Framework 2.3 Dover District Council Heritage Strategy 2.4 Statutory Legislation 3 Designated Heritage Assets in the Study Area 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Conservation Areas 3.3 Listed Buildings 3.4 Scheduled Ancient Monuments 3.5 Summary 4 Historical Resources 4.1 Historical Background of the Study Area 5 Archaeological Resources and Potential 5.1 Geology and Topography 5.2 Archaeological Introduction 5.3 Non Designated Heritage Assets within the Study Area 5.4 General Summary of the Archaeology in its Landscape Context 6 Land Development 6.1 Cartographic Evidence for the Development of the Site 6.2 Cartographic Summary 7. The Site Inspection 7.1 The Site Inspection 7.2 Summary 8 Impact Assessment 8.1 Introduction 8.2 Definitions of Level of Impact 8.3 Impacts Defined by the Study 8.4 Potential Impact of the Development of the Site 8.5 Potential Effects of Construction on the Archaeological Resource 9. Summary and Discussion 10 Acknowledgements 11 Sources Consulted Appendices 1 Listed Buildings within the Study Area 2 Gazetteer of Archaeological Sites Figures 1. -

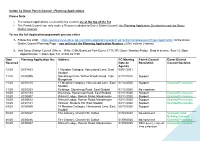

Planning Applications Please Note

Sutton by Dover Parish Council - Planning Applications Please Note: The newest applications received by the Council are at the top of the list The Parish Council can only make a Recommendation to Dover District Council, the Planning Application Decision is made by Dover District Council. To see the full Application paperwork you can either 1. Follow this LINK https://publicaccess.dover.gov.uk/online-applications/search.do?action=simple&searchType=Application to the Dover District Council Planning Page – you will need the Planning Application Number - (See column 2 below) 2. Visit Dover District Council Offices – White Cliffs Business Park Dover CT16 3PJ Open: Monday-Friday, Drop in service: 9am-12.30pm Appointments: 1.30pm-5pm Tel. 01304 821199 Date Planning Application No: Address PC Meeting Parish Council Dover District Received Date on Resolution Council Decision Agenda 12/20 20/01483 1 Meadow Cottages, Homestead Lane, East 05/01/2021 Studdal 11/20 20/00955 Stoneheap Farm, Willow Woods Road, Little 01/12/2020 Support Mongeham 11/20 20/01215 11 Meadow Cottages, Homestead Lane, East 01/12/2020 Support Granted Permission Studdal 11/20 20/01203 Fieldings, Stoneheap Road, East Studdal 01/12/2020 No response 10/20 20/01184 Bherunda, Stoneheap Road, East Studdal 03/11/2020 Support Granted Permission 10/20 20/00807 Warcott Lodge, Roman Road, Maydensole 03/11/2020 Support Granted Permission 10/20 20/00542 Warcott Lodge, Roman Road, Maydensole 03/11/2020 Support Granted Permission 10/20 20/01141 Hillcrest, Strakers Hill, East Studdal 03/11/2020 Support Granted Permission 09/20 20/00865 14 Meadow Cottages, Homestead Lane, East 06/10/2020 Support Studdal 08/20 20/00847 The Granary, Church Hill, Sutton 01/09/2020 No comment Granted Listed Building Consent 08/20 20/00846 The Granary, Church Hill, Sutton 01/09/2020 No comment Granted Permission 08/20 20/00807 Warcott Lodge, Roman Road, Maydensole 01/09/2020 DDC query, request Granted Permission time extension. -

Dover District Council

Registered Applications for week ending 24/08/12 DOVER DISTRICT COUNCIL Alkham DOV/12/00638 Certificate of lawfulness (existing) for the erection of stables and stores Ferndown Stables, Chalksole Green, Alkham, CT15 7EE Aylesham DOV/12/00605 Erection of a two storey rear extension 16 Burgess Road, Aylesham, CT3 3AU Deal DOV/12/00639 Erection for single storey side and rear extension, a detached garage and a side and rear dormer roof extension (existing garage/workshop to be demolished) 56 Golf Road, Deal, CT14 6QB DOV/12/00647 Erection of a single storey rear extension and installation of replacement windows to the front (existing rear extension to be demolished) 30 St Georges Road, Deal, CT14 6BA DOV/12/00648 Demolition of rear extension 30 St Georges Road, Deal, CT14 6BA Dover DOV/12/00430 Outline application for the erection of two semi-detatched dwellings Site Rear of Gordon Bennett & Gordon Lodge, Vale View Road, Dover CT17 9NP DOV/12/00626 Part change of use and conversion of first floor to 15 one bedroom flats and 2 two bedroom flats and associated external alterations Part of First Floor, Charlton Centre, High Street, Dover DOV/12/00646 Display of internally illuminated fascia, projecting and internal window signs 24 Pencester Road, Dover, CT16 1BW DOV/12/00649 Renewal of planning permission DOV/07/00801 for the erection of storage unit St Nicholas Church, The Linces, Dover, CT16 2BN Eythorne DOV/12/00645 Erection of a porch extension and external alterations Park End House, The Street, Eythorne, CT15 4BG Northbourne DOV/12/00642