Black Lane (PINS Ref: ROW–3237045) BHS Comment on Objector’S Statement of Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Ash and Its Churches

A History of Ash and its Churches The present parish of Ash, more than 7,000 acres in extent and one of the largest in Kent, was once only a part of the great manor of Wingham. Originally a royal manor, Wingham was given by King Athelstan of Kent to the See of Canterbury about 850 : it covered the present parishes of Ash, Goodnestone, Nonington, Wingham and parts of Staple and Womenswold. In a list of churches probably made in 1071, in which 'Aesce' is said to belong to Wingham, mention is also made of an apparently more important church 'de Raette', as well as one at 'Fleota' belonging to the manor of Folkestone. If, as seems likely, 'de Raette' refers to Richborough, this is the only record of that church; but the chapel of Fleet, actually within the 3rd century Roman walls of Richborough Castle, continued in use until the 16th century. Leland in the time of Henry VIII wrote that 'withyn the castel is a lytle paroche Chirch of S. Augustine'. It was believed that when St. Augustine first stepped ashore in England in 597 the impression of his foot was miraculously left upon a stone. This relic was afterwards kept in this chapel dedicated to him, and pilgrims flocked there upon the anniversary of the landing to pray and to recover their health. Excavations have uncovered the ground plan of the chapel, and confirm that it was pre-Norman in origin. Excavations in the northwest comer of the Roman fort have also, revealed the foundations and font of an even earlier church of c.400, one of the earliest Christian structures known in Britain. -

Agenda March 2021

GREAT MONGEHAM PARISH COUNCIL Thornton House, Thornton Lane, Eastry, Sandwich, Kent, CT13 OEU Tel: 01304 746036/07903 739792 25th February 2021 To all members of the Parish Council You are hereby summoned to attend the Ordinary Meeting of the Great Mongeham Parish Council to be held on Thursday 4th March 2021 at 7.30pm, virtually using Zoom, for the purposes of transacting the following business. Joanna Jones Clerk to the Parish Council AGENDA 1. APOLOGIES To receive apologies for non attendance at the meeting. The meeting will be adjourned so that members of the public can speak. Members of the public are welcome to attend but can only speak during the designated timeslot. Anyone wishing to attend please email [email protected] for the meeting details, providing your name and address. 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST To record declarations and reasons for interest from members relating to items on the agenda. 3. MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING a) To confirm the minutes of the Ordinary meeting of the Parish Council held on 4th February 2021. 4. ACTIONS FROM THE LAST MEETING To receive information resulting from actions generated at the last meeting. 5. CORONAVIRUS UPDATE a) Information from DDC, KCC and Central Government All emails received in connection with the Coronavirus and vaccinations have been forwarded to Council members as received. The situation changes frequently and the information is fluid in nature. NALC and SLCC continue to strongly advise local councils to continue to meet remotely, without the need for face to face contact. 6. PLANNING a) Planning Applications To discuss any planning applications received prior to the meeting. -

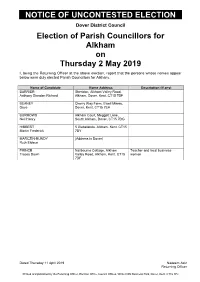

Parish Council (Uncontested)

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Dover District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Alkham on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Alkham. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BARRIER Sheridan, Alkham Valley Road, Anthony Standen Richard Alkham, Dover, Kent, CT15 7DF BEANEY Cherry Way Farm, Ewell Minnis, Dave Dover, Kent, CT15 7EA BURROWS Alkham Court, Meggett Lane, Neil Henry South Alkham, Dover, CT15 7DG HIBBERT 5 Glebelands, Alkham, Kent, CT15 Martin Frederick 7BY MARCZIN-BUNDY (Address in Dover) Ruth Eldeca PRINCE Nailbourne Cottage, Alkham Teacher and local business- Tracey Dawn Valley Road, Alkham, Kent, CT15 woman 7DF Dated Thursday 11 April 2019 Nadeem Aziz Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Election Office, Council Offices, White Cliffs Business Park, Dover, Kent, CT16 3PJ NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Dover District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Ash on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Ash. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) CHANDLER Hadaways, Cop Street, Ash, Peter David Canterbury, CT3 2DL ELLIS 60A The Street, Ash, Canterbury, Reginald Kevin Kent, CT3 2EW HARRIS-ROWLEY (Address in Dover) Andrew Raymond LOFFMAN (Address in Dover) Jeffrey Philip PORTER 38 Sandwich Rd, Ash, Canterbury, Martin -

Dover Grammar School for Girls Page 1 of 5 for Aylesham, Elvington, Eythorne and Whitfield

Buses serving Dover Grammar School for Girls page 1 of 5 for Aylesham, Elvington, Eythorne and Whitfield Getting to school 89 89X Going from school 89 88 Aylesham Baptist Church 0715 0720 Park Avenue 1544 Aylesham Oakside Road 0717 0722 Frith Road 1540 - Cornwallis Avenue Shops 0720 0725 Buckland Bridge 1552 1552 Queens Road 0723 0729 Tesco superstore 1600 - Snowdown 0726 - Whitfield The Archer 1602 1602 Nonington Village Hall 0731 - Whitfield Farncombe Way - 1604 Elvington St. John’s Road 0738 - Whitfield Forge Path 1604 1609 Eythorne EKLR Station 0741 - Eythorne EKLR Station 1612 1617 Waldershare Park 0745 - Elvington St. John’s Road 1615 1620 Whitfield Forge Path 0750 - Nonington Village Hall 1622 Whitfield Farncombe Way - 0758 Snowdown 1627 Whitfield The Archer Archers Crt Rd 0753 0801 Aylesham Baptist Church 1630 Tesco superstore 0759 - Aylesham Oakside Road 1632 Roosevelt Road - 0811 Aylesham Cornwallis Ave Shops 1635 Buckland Bridge 0809 0813 Queens Road 1638 Frith Road 0814 0818 This timetable will apply from 5th January 2020 @StagecoachSE www.stagecoachbus.com Buses serving Dover Grammar School for Girls page 2 of 5 for Sandwich, Eastry, Chillenden, Nonington Shepherdswell, Lydden, Temple Ewell and River Getting to school 80 92 89B 88A 96 Going from school 92 96 89B 80 80 88 Sandwich Guildhall 0716 Park Avenue 1543 1535 1544 Eastry The Bull Inn - 0723 Dover Pencester Road Stop B 1545 - - - Tilmanstone Plough & Harrow - 0730 Templar Street 1548 - 1540 - - Chillenden The Griffin’s Head - - 0737 Buckland Bridge Whitfield Ave - - -

Dover District Council Submission on Ward Patterns

Dover District Council Submission on Ward Patterns 6 April 2018 [This page has been intentionally left blank] Contents Section Page Foreword from the Chief Executive, Nadeem Aziz 3 Part 1 Summary of Proposals 5 Part 2 Development of Proposals 6 • Introduction 7 • Statutory Criteria for Ward Patterns 7 • Electoral Forecasting 8 • How did the Council develop its proposed ward pattern? 14 Part 3 Proposed Ward Pattern • Overview of Proposed New Ward Pattern 18 • Ward 1 Little Stour & Ashstone (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 21 • Ward 2 Sandwich (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 23 • Ward 3 Aylesham Rural (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 25 • Ward 4 Eastry Rural (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 27 • Ward 5 Coldred (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 29 • Ward 6 Whitfield Rural (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 31 • Ward 7 St Margaret’s-at-Cliffe (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 33 • Ward 8 Capel, Hougham and Alkham (Map, Electoral Data and 35 Rationale) • Ward 9 River (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 37 • Ward 10 Walmer and Kingsdown (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 39 • Ward 11 North Deal and Sholden (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 41 • Ward 12 South Deal and Castle (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 43 • Ward 13 Pier and Priory (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 45 • Ward 14 Maxton, Elms Vale & Tower Hamlets (Map, Electoral Data 47 and Rationale) • Ward 15 Dover Central (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 49 • Ward 16 St Radigund’s and Buckland (Map, Electoral Data and 51 Rationale) 1 | Page [This page has been intentionally left blank] 2 | Page Foreword Nadeem Aziz Chief Executive This document represents the formal response of Dover District Council to the invitation from the Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) to submit ward pattern proposals to accommodate a future council size of 32 councillors. -

Draft Local Plan Proposed Site Allocations - Reasons for Site Selection

Topic Paper: Draft Local Plan Proposed Site Allocations - Reasons for Site Selection Dover District Local Plan Supporting document The Selection of Site Allocations for the Draft Local Plan This paper provides the background to the selection of the proposed housing, gypsy and traveller and employment site allocations for the Draft Local Plan, and sets out the reasoning behind the selection of specific site options within the District’s Regional, District, Rural Service, Local Centres, Villages and Hamlets. Overarching Growth Strategy As part of the preparation of the Local Plan the Council has identified and appraised a range of growth and spatial options through the Sustainability Appraisal (SA) process: • Growth options - range of potential scales of housing and economic growth that could be planned for; • Spatial options - range of potential locational distributions for the growth options. By appraising the reasonable alternative options the SA provides an assessment of how different options perform in environmental, social and economic terms, which helps inform which option should be taken forward. It should be noted, however, that the SA does not decide which spatial strategy should be adopted. Other factors, such as the views of stakeholders and the public, and other evidence base studies, also help to inform the decision. The SA identified and appraised five reasonable spatial options for growth (i.e. the pattern and extent of growth in different locations): • Spatial Option A: Distributing growth to the District’s suitable and potentially suitable housing and employment site options (informed by the HELAA and Economic Land Review). • Spatial Option B: Distributing growth proportionately amongst the District’s existing settlements based on their population. -

The East Kent Ploughing Match Association Women's Section. 1951

The East Kent Ploughing Match Association Women's Section. 1951 was the first year that there was a Women's Section of the E.K.P.M.A. which was held at Adisham Court on the 18th October. Records show that a Nonington Agriculture Association P.M. was held as long ago as 1840 and continued for about 90 years with some breaks most notably during the two World Wars and during "Difficulties in the Agricultural Situation" in depression of the 1930's". Soon after the end of the Second World War, on 25th October 1945,the Shepherdswell and District P.M.Association, as it was then called, held the first Match at West Court Shepherdswell where, despite rain and gale force winds,it is thaught about 1000 people attended "Ladies"were involved selling catalogues at a shilling [5p] a time. Angela Coleman and Kate Hume being involved almost from the beginning. In 1950 the Association changed its name to the East Kent P.M.A.and the possibility of a Womens Section was suggested by Ella Robertson, John Robertson's wife. of Appleton Manor, but it was not thought to be financially possible that year. However she and a number of the P.M Committee Members' wives formed a Committee of their own and were able to put on their first Show the following year. They were a remarkable collection of Ladies, mostly Farmer's wives, the majority in their 40's or early 50's, who had worked so hard during the War coping with shortages and the worry of children being evacuated from this hot spot of East Kent, followed by a difficult 5 years trying to get back to normal. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

List of applications decided between 18/05/2020 and 25/05/2020 (Decision Date) REFERENCE ADDRESS PROPOSAL DECISION DATE DECISION CON/19/00838/M 45 Eythorne Road 26 - Retaining Wall 18-May-2020 CONAP Shepherdswell Kent CON/18/01334/C The Charity Inn 9 - Construction Management 18-May-2020 COAPP The Street Plan Woodnesborough Sandwich Kent CT13 0ND CON/19/01361/D Site At 12 - Foul Water 19-May-2020 COAPP Summerfield Farm Barnsole Road Staple Kent CON/18/01334/B The Charity Inn 4 - Levels 20-May-2020 COAPP The Street Woodnesborough Sandwich Kent CT13 0ND CON/19/00838/F 45 Eythorne Road 16 - Surface Water 21-May-2020 CONAP Shepherdswell Kent CON/20/00123/C 223 Telegraph 10 - Suds Former REF 21-May-2020 CONAP Road CON/19/01157/C Deal Kent CT14 9DU REFERENCE ADDRESS PROPOSAL DECISION DATE DECISION CON/15/00336/E Denne Court Farm Condition 18 - Archaeological 21-May-2020 COPART Hammill watching brief Woodnesborough CT13 0EG 20/00320 White Gables Erection of a single storey rear 19-May-2020 GTD Woodnesborough extension Lane Eastry CT13 0DT 20/00323 Carfax House Erection of a two storey side 19-May-2020 GTD The Street extension with Juliette balcony Stourmouth and balustrade, a single storey CT3 1HY rear extension and side porch (existing single storey side extension and porch to be demolished) 20/00287 Historic Panel Display of a non-illuminated 21-May-2020 GADV Wellington Parade public information noticeboard Walmer relocated from Walmer Car Park 20/00328 8 Bluebell Drive Certificate of lawfulness 21-May-2020 CLPG Aylesham (proposed) for the erection of CT3 3GX rear conservatory, garage conversion and front canopy porch 20/00331 Manor Farm Prior approval for the change 18-May-2020 ARPR Willow Woods of the agricultural building to Road 3no. -

Situation of Polling Stations

SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS Dover District Council Election of the Police and Crime Commissioner for the Kent Police Area Thursday 6 May 2021 The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Station Ranges of electoral register numbers Situation of Polling Station Number of persons entitled to vote thereat Deal Christian Fellowship Hall, Sutherland Road, Deal, 1 AMD1-1 to AMD1-2007 CT14 9TQ Linwood Youth Centre (New), Victoria Park, Park Avenue, 2 AMD2-1 to AMD2-1545 Deal, CT14 9UU Scout Hall (behind Warden House School), London Road, 3 AMD3-1 to AMD3-1363 Deal, CT14 9PR Deal Pentecostal Church, 69 Mill Hill, Deal, CT14 9EW 4 AMH1-1 to AMH1-2288 The Godric Centre, Rear of St John`s R C Church, St 5 AMH2-1 to AMH2-1427 Richard`s Road, Deal, CT14 9LD The Sports Centre, Off Cavell Square, Deal, CT14 9HN 6 AMH3-1 to AMH3-2232 The Golf Road Centre, 28 Golf Road, Deal, Kent, CT14 7 AN1-1 to AN1-2001 6PY The Golf Road Centre, 28 Golf Road, Deal, Kent, CT14 7 PSHN-1 to PSHN-100 6PY Cleary Hall, Landmark Centre, 129 High Street, Deal, 8 AN2-1 to AN2-1764 CT14 6BB Deal Library, Broad Street, Deal, CT14 6ER 9 AN3-1/1 to AN3-1173/2 Walmer Chapel (Rear Hall), 30 Station Road, Walmer, 10 AW1-1 to AW1-2122 Deal, CT14 7QS Walmer Parish Hall, Dover Road, Walmer, Deal, CT14 11 AW2-1 to AW2-2406 7JH St Saviour`s Church, The Strand, Walmer, Deal, CT14 12 AW3-1 to AW3-1294 7DY Walmer Sea Scout Hall, Marine Road, Walmer, Deal, 13 AW4N-1/1 to AW4N-790 CT14 7DN Scout H.Q., The Street, Sholden, Deal, -

BOYS of KENT

BOYS of KENT Original source - William BOYS & Thomas BRETT pedigree in SoG additional material from John V. Boys, Malcolm Boyes, Jenny Treadgold, Peter Walkerley, Wendy Sveistrup, Colin Boyes, The following text is at the commencement of the pedigree..... DJB This pedigree was drawn by me from various parochial registers; from sepulchral monuments; from wills registered in London; from Heraldic visitations of 1574, 1619, 1663, and from other records of the Heralds office, obligingly furnished by Sir Isaac Heard, Garter King at arms; from papers communicated by Messrs. Thomas and Nicholas Brett, of Spring-grove in Wye; and from private evidences of my own family. Besides the papers above mentioned in the possession of Messrs. Brett, I have derived assistance from the hand-writing of Dr Thomas Brett, containing a history of the Betteshanger branch, to which the Doctor was allied by the marriage of his father with Laeatitia daughter of John Boys Esq. A certificate of marriage ( an extract of which I have hereto subjoined ) is annexed to the papers of Spring-grove, in the hand of the Rev. Mr. Nicholas Brett, only son of the Doctor. The Pedigree he mentions was by no means complete, but yet of use to me, as it is particularly served to direct the enquiries necessary to the making mine so perfect as it is; the Surrey branch, ie. from the first Anthony downwards, being the only part of it wherein I have been under the necessity of trusting to the information of others. I am proud to acknowledge my obligation to William Boteler, Esq., of Eastry F.S.A as well as his unwearied assistance in drawing out the Pedigree, and for his affectionate compliance with my wishes to examine every part of the evidence adduced and attest its authenticity. -

Beresford Grove, Aylesham, Canterbury, Kent, CT3 3FA LOCATION Contents

Beresford Grove, Aylesham, Canterbury, Kent, CT3 3FA LOCATION Contents LOCATION Introduction An invaluable insight into your new home This Location Information brochure offers an informed overview of Beresford Grove as a potential new home, along with essential material about its surrounding area and its local community. It provides a valuable insight for any prospective owner or tenant. We wanted to provide you with information that you can absorb quickly, so we have presented it as visually as possible, making use of maps, icons, tables, graphs and charts. Overall, the brochure contains information about: The Property - including property details, floor plans, room details, photographs and Energy Performance Certificate. Transport - including locations of bus and coach stops, railway stations and ferry ports. Health - including locations, contact details and organisational information on the nearest GPs, pharmacies, hospitals and dentists. Local Policing - including locations, contact details and information about local community policing and the nearest police station, as well as police officers assigned to the area. Education - including locations of infant, primary and secondary schools and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for each key stage. Local Amenities - including locations of local services and facilities - everything from convenience stores to leisure centres, golf courses, theatres and DIY centres. Regal Estates 57 Castle Street, Canterbury, CT1 2PY 01227 763888 LOCATION The Property BERESFORD GROVE, CANTERBURY £255,000 x4 x1 x2 Bedrooms Living Rooms Bathrooms Where you are BERESFORD GROVE, CANTERBURY LOCATION £255,000 Regal Estates 57 Castle Street, Canterbury, CT1 2PY 01227 763888 BERESFORD GROVE, CANTERBURY LOCATION £255,000 Regal Estates 57 Castle Street, Canterbury, CT1 2PY 01227 763888 LOCATION Features BEAUTIFULLY PRESENTED FOUR BEDROOM TOWN HOUSE WITH PARKING AND NO FORWARD CHAIN. -

THE BARFRESTONE Conundrum: ‘MUCH RESTORED’ but ‘VIRTUALLY UNALTERED’

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 134 2014 THE BARFRESTONE ConUNDRUM: ‘MUCH RESTORED’ BUT ‘VIRTUALLY UNALTERED’ CHARLES COULSON R.C. Hussey’s careful memorandum in Archaeologia Cantiana (1886) of his conscientious work in 1839-41 failed to shield him from criticism during his own lifetime of having falsified a ‘gem’. This tendency has continued, even (especially) in scholarly publications such as A.W. Clapham’s , Romanesque Architecture (1934). Belief that the church was ‘rebuilt’ has persisted and has recently been re-stated in Norman Churches in Canterbury Diocese (Berg. M. and Jones, H., 2009). This paper summarises, as succinctly as possible, the case vindicating Hussey as well as the authenticity of St Nicholas Church. How it can be that a very early ‘Victorian restoration’ should not have tampered with the architectural evidence is a very persistent concern. John Betjeman’s, Collins Guide to Parish Churches (1958, p. 238), puts the perceived ambiguity very neatly regarding Barfrestone. ‘St Nicholas Church the best Norman church in Kent, is virtually unaltered, though much restored 1839-41 by Blore’. Had Edward Blore, the versatile architect of lucrative country houses in the Gothic Style,1 truly done the ‘repairs’ which his 1839 report recommended doubt would be in order.2 Fortunately, however, they were entrusted to Thomas Rickman and Richard Charles Hussey, pupil then partner of the ailing but scholarly pioneer Gothicist.3 At the end of his life, facing criticism from an architecturally and historically aware generation, Hussey in 1886 published in this Journal a meticulous record and apologia.4 The present author’s analysis of this set out below, pictorially and diagrammatically, using in part the very careful (but not infallible) drawings commissioned for vol.