THE BARFRESTONE Conundrum: ‘MUCH RESTORED’ but ‘VIRTUALLY UNALTERED’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shepherdswell · Dover · Kent Ct15 7Lx

Land & Property Experts LONG LANE FARM LONG LANE · SHEPHERDSWELL · DOVER · KENT CT15 7LX LOCATION LONG LANE FARM Long Lane Farm is situated either side of Long Lane, immediately to the north of the village of Shepherdswell in LONG LANE East Kent. Shepherdswell benefits from a range of local facilities and amenities along with a main line rail SHEPHERDSWELL station with links to Canterbury and therefore London. DOVER Dover, Folkstone and Canterbury are all within a 10 mile radius and can provide a more comprehensive range of KENT CT15 7LX facilities and amenities along with schooling and national and international rail links to London and or the Continent. Shepherdswell - 1 mile Please see the Location Plan below which shows the location of the property in relation to the surrounding Aylesham - 3 miles towns and villages. Dover - 6 miles Folkstone - 10 miles DIRECTIONS Canterbury - 10 miles From the centre of Shepherdswell, go north on Eythorne Road towards Deal and once you have passed the Co- An opportunity to purchase an agricultural Op and crossed the adjacent railway bridge, carry on for a further half a mile and shortly after crossing the East holding with significant range of farm buildings Kent Light railway take the left onto Barfrestone Road. Follow this road for approximately a quarter of a mile some with planning permission, detached and take the first left onto Long Lane. The farmhouse, yard and buildings at Long Lane Farm are approximately farmhouse and approximately 100 acres of a quarter of a mile on your left. workable land. From Canterbury, take the A2 south east towards Dover, take the exit off to Barfrestone which takes you onto • Lot 1 – Farmhouse, garden and paddock land – 1.21 Westcourt Road. -

A History of Ash and Its Churches

A History of Ash and its Churches The present parish of Ash, more than 7,000 acres in extent and one of the largest in Kent, was once only a part of the great manor of Wingham. Originally a royal manor, Wingham was given by King Athelstan of Kent to the See of Canterbury about 850 : it covered the present parishes of Ash, Goodnestone, Nonington, Wingham and parts of Staple and Womenswold. In a list of churches probably made in 1071, in which 'Aesce' is said to belong to Wingham, mention is also made of an apparently more important church 'de Raette', as well as one at 'Fleota' belonging to the manor of Folkestone. If, as seems likely, 'de Raette' refers to Richborough, this is the only record of that church; but the chapel of Fleet, actually within the 3rd century Roman walls of Richborough Castle, continued in use until the 16th century. Leland in the time of Henry VIII wrote that 'withyn the castel is a lytle paroche Chirch of S. Augustine'. It was believed that when St. Augustine first stepped ashore in England in 597 the impression of his foot was miraculously left upon a stone. This relic was afterwards kept in this chapel dedicated to him, and pilgrims flocked there upon the anniversary of the landing to pray and to recover their health. Excavations have uncovered the ground plan of the chapel, and confirm that it was pre-Norman in origin. Excavations in the northwest comer of the Roman fort have also, revealed the foundations and font of an even earlier church of c.400, one of the earliest Christian structures known in Britain. -

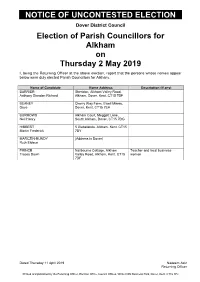

Parish Council (Uncontested)

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Dover District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Alkham on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Alkham. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BARRIER Sheridan, Alkham Valley Road, Anthony Standen Richard Alkham, Dover, Kent, CT15 7DF BEANEY Cherry Way Farm, Ewell Minnis, Dave Dover, Kent, CT15 7EA BURROWS Alkham Court, Meggett Lane, Neil Henry South Alkham, Dover, CT15 7DG HIBBERT 5 Glebelands, Alkham, Kent, CT15 Martin Frederick 7BY MARCZIN-BUNDY (Address in Dover) Ruth Eldeca PRINCE Nailbourne Cottage, Alkham Teacher and local business- Tracey Dawn Valley Road, Alkham, Kent, CT15 woman 7DF Dated Thursday 11 April 2019 Nadeem Aziz Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Election Office, Council Offices, White Cliffs Business Park, Dover, Kent, CT16 3PJ NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Dover District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Ash on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Ash. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) CHANDLER Hadaways, Cop Street, Ash, Peter David Canterbury, CT3 2DL ELLIS 60A The Street, Ash, Canterbury, Reginald Kevin Kent, CT3 2EW HARRIS-ROWLEY (Address in Dover) Andrew Raymond LOFFMAN (Address in Dover) Jeffrey Philip PORTER 38 Sandwich Rd, Ash, Canterbury, Martin -

Notes on Roman Roads in East Kent Margary

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society NOTES ON ROMAN ROADS IN EAST KENT By IvAN D. MARGARY, F.S.A. THE Roman roads of East Kent are generally so obvious and well known that no further description of them seems necessary. There are, however, a few points at which the line is doubtful or where topographical problems admit of some discussion, and it is in considera- tion of these that the following notes are offered. They are based upon field observation made during a visit of some days to the district in June, 1947. STONE STREET—LYMPNE TO CANTERBURY The very striking directness of this road makes it clear that its purpose was to link Canterbury with the Roman port at Lympne. This was probably situated below the old cliffs, near the hamlet of West Hythe, to which access is given by a convenient combo in the cliffs at that point from Shipway Cross above. The Saxon Shore fort at Stutfall Castle was, of course, a late Roman construction, much later than Stone Street, and was probably connected to West Hythe by a spur road below the cliffs, for access to it from Lympne, directly above, would have been awkward. It is to Shipway Cross and the head of the combe that the main alignment of Stone Street is exactly directed. Although it has now disappeared between the Cross and New Inn Green, there are distinct traces of its scattered stone metalling in the field to the south of the Green, while portions of hedgerows and a footpath mark some parts of its course there. -

Black Lane (PINS Ref: ROW–3237045) BHS Comment on Objector’S Statement of Case

Black Lane (PINS ref: ROW–3237045) BHS comment on objector’s statement of case A. Introduction A.1. These are the comments on the British Horse Society (BHS) on the statement of case submitted by ET Landnet on behalf of its client, Mr Fox-Pitt. We refer below to the position represented by ET Landnet as the case made by ‘the objector’. We refer to refer- ences in the BHS statement of case as ‘SOC, X.Y’, meaning item Y in part X of the state- ment of case. We refer to the order way as ‘Black Lane’. We refer to numbered paragraphs in the objector’s statement of case as ‘ETL, para.X’. A.2. We make the following observation in opening. A.3. Firstly, we recognise, as the objector observes, that there are inconsistencies in the evidence in support of confirming the order. That is why there is an order before the Secretary of State. If Black Lane had remained in continuous and unchallenged use up to the present day, the whole of it would have been readily identified and added to the defin- itive map and statement under Part IV of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. As it is, use has been in decline since the early nineteenth century (SOC, I.G), and only part was recorded under the 1949 Act — and then only as an apparently dead- end footpath (see our comments at para.C.20 below). A.4. Secondly, the Knowlton estate was acquired in 1904 by Maj. Francis Elmer Speed,1 of whom Marietta Fox-Pitt (née Speed), the present owner of Knowlton Court, is a descendent. -

Dover Grammar School for Girls Page 1 of 5 for Aylesham, Elvington, Eythorne and Whitfield

Buses serving Dover Grammar School for Girls page 1 of 5 for Aylesham, Elvington, Eythorne and Whitfield Getting to school 89 89X Going from school 89 88 Aylesham Baptist Church 0715 0720 Park Avenue 1544 Aylesham Oakside Road 0717 0722 Frith Road 1540 - Cornwallis Avenue Shops 0720 0725 Buckland Bridge 1552 1552 Queens Road 0723 0729 Tesco superstore 1600 - Snowdown 0726 - Whitfield The Archer 1602 1602 Nonington Village Hall 0731 - Whitfield Farncombe Way - 1604 Elvington St. John’s Road 0738 - Whitfield Forge Path 1604 1609 Eythorne EKLR Station 0741 - Eythorne EKLR Station 1612 1617 Waldershare Park 0745 - Elvington St. John’s Road 1615 1620 Whitfield Forge Path 0750 - Nonington Village Hall 1622 Whitfield Farncombe Way - 0758 Snowdown 1627 Whitfield The Archer Archers Crt Rd 0753 0801 Aylesham Baptist Church 1630 Tesco superstore 0759 - Aylesham Oakside Road 1632 Roosevelt Road - 0811 Aylesham Cornwallis Ave Shops 1635 Buckland Bridge 0809 0813 Queens Road 1638 Frith Road 0814 0818 This timetable will apply from 5th January 2020 @StagecoachSE www.stagecoachbus.com Buses serving Dover Grammar School for Girls page 2 of 5 for Sandwich, Eastry, Chillenden, Nonington Shepherdswell, Lydden, Temple Ewell and River Getting to school 80 92 89B 88A 96 Going from school 92 96 89B 80 80 88 Sandwich Guildhall 0716 Park Avenue 1543 1535 1544 Eastry The Bull Inn - 0723 Dover Pencester Road Stop B 1545 - - - Tilmanstone Plough & Harrow - 0730 Templar Street 1548 - 1540 - - Chillenden The Griffin’s Head - - 0737 Buckland Bridge Whitfield Ave - - -

Dover District Council Submission on Ward Patterns

Dover District Council Submission on Ward Patterns 6 April 2018 [This page has been intentionally left blank] Contents Section Page Foreword from the Chief Executive, Nadeem Aziz 3 Part 1 Summary of Proposals 5 Part 2 Development of Proposals 6 • Introduction 7 • Statutory Criteria for Ward Patterns 7 • Electoral Forecasting 8 • How did the Council develop its proposed ward pattern? 14 Part 3 Proposed Ward Pattern • Overview of Proposed New Ward Pattern 18 • Ward 1 Little Stour & Ashstone (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 21 • Ward 2 Sandwich (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 23 • Ward 3 Aylesham Rural (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 25 • Ward 4 Eastry Rural (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 27 • Ward 5 Coldred (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 29 • Ward 6 Whitfield Rural (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 31 • Ward 7 St Margaret’s-at-Cliffe (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 33 • Ward 8 Capel, Hougham and Alkham (Map, Electoral Data and 35 Rationale) • Ward 9 River (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 37 • Ward 10 Walmer and Kingsdown (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 39 • Ward 11 North Deal and Sholden (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 41 • Ward 12 South Deal and Castle (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 43 • Ward 13 Pier and Priory (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 45 • Ward 14 Maxton, Elms Vale & Tower Hamlets (Map, Electoral Data 47 and Rationale) • Ward 15 Dover Central (Map, Electoral Data and Rationale) 49 • Ward 16 St Radigund’s and Buckland (Map, Electoral Data and 51 Rationale) 1 | Page [This page has been intentionally left blank] 2 | Page Foreword Nadeem Aziz Chief Executive This document represents the formal response of Dover District Council to the invitation from the Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) to submit ward pattern proposals to accommodate a future council size of 32 councillors. -

Eastry, Sandwich

Eastry, Sandwich Sunnyside Selson Eastry Sandwich Kent CT13 0EF Description • Bedroom 15'8 x 10'0 Ground Floor (4.78m x 3.05m) With built-in • Lobby wardrobes • Hall • Bedroom • Lounge 15'4 x 10'5 24'8 x 12'2 (4.67m x 3.18m) (7.52m x 3.71m) With built-in cupboard • Dining Room 12'2 x 10'0 • Bedroom (3.71m x 3.05m) 9'1 x 8'4 (2.77m x 2.54m) • Kitchen/Breakfast Plus built-in Room wardrobe 13'3 x 10'0 (4.04m x 3.05m) • Bedroom 8'6 x 6'11 • Conservatory (2.59m x 2.11m) 25'6 x 8'0 (7.77m x 2.44m) • WC • Boiler Room External • Bath & Shower • Driveway Room 13'10 x 9'2 • Rear Garden (4.22m x 2.79m) Mainly laid to lawn with patio area, a First Floor greenhouse, garden room, • Landing summerhouse and log cabin Property Sunnyside is a delightful four-bedroom family home which provides good sized living accommodation and boasts wonderful countryside views. Located in the hamlet of Selson, close to the village of Eastry, the property is ideally situated between Sandwich and Deal as well as being within easy reach of Canterbury. The property provides spacious accommodation throughout with a large entrance lobby, generous lounge with feature fireplace, fully fitted kitchen, separate dining area and a conservatory to enjoy the beautiful garden and field views. The ground floor is completed with a four-piece family bathroom. To the first floor there are four good sized bedrooms, three of which have fitted wardrobes and the master bedroom boasts fabulous views to the rear. -

Draft Local Plan Proposed Site Allocations - Reasons for Site Selection

Topic Paper: Draft Local Plan Proposed Site Allocations - Reasons for Site Selection Dover District Local Plan Supporting document The Selection of Site Allocations for the Draft Local Plan This paper provides the background to the selection of the proposed housing, gypsy and traveller and employment site allocations for the Draft Local Plan, and sets out the reasoning behind the selection of specific site options within the District’s Regional, District, Rural Service, Local Centres, Villages and Hamlets. Overarching Growth Strategy As part of the preparation of the Local Plan the Council has identified and appraised a range of growth and spatial options through the Sustainability Appraisal (SA) process: • Growth options - range of potential scales of housing and economic growth that could be planned for; • Spatial options - range of potential locational distributions for the growth options. By appraising the reasonable alternative options the SA provides an assessment of how different options perform in environmental, social and economic terms, which helps inform which option should be taken forward. It should be noted, however, that the SA does not decide which spatial strategy should be adopted. Other factors, such as the views of stakeholders and the public, and other evidence base studies, also help to inform the decision. The SA identified and appraised five reasonable spatial options for growth (i.e. the pattern and extent of growth in different locations): • Spatial Option A: Distributing growth to the District’s suitable and potentially suitable housing and employment site options (informed by the HELAA and Economic Land Review). • Spatial Option B: Distributing growth proportionately amongst the District’s existing settlements based on their population. -

The East Kent Ploughing Match Association Women's Section. 1951

The East Kent Ploughing Match Association Women's Section. 1951 was the first year that there was a Women's Section of the E.K.P.M.A. which was held at Adisham Court on the 18th October. Records show that a Nonington Agriculture Association P.M. was held as long ago as 1840 and continued for about 90 years with some breaks most notably during the two World Wars and during "Difficulties in the Agricultural Situation" in depression of the 1930's". Soon after the end of the Second World War, on 25th October 1945,the Shepherdswell and District P.M.Association, as it was then called, held the first Match at West Court Shepherdswell where, despite rain and gale force winds,it is thaught about 1000 people attended "Ladies"were involved selling catalogues at a shilling [5p] a time. Angela Coleman and Kate Hume being involved almost from the beginning. In 1950 the Association changed its name to the East Kent P.M.A.and the possibility of a Womens Section was suggested by Ella Robertson, John Robertson's wife. of Appleton Manor, but it was not thought to be financially possible that year. However she and a number of the P.M Committee Members' wives formed a Committee of their own and were able to put on their first Show the following year. They were a remarkable collection of Ladies, mostly Farmer's wives, the majority in their 40's or early 50's, who had worked so hard during the War coping with shortages and the worry of children being evacuated from this hot spot of East Kent, followed by a difficult 5 years trying to get back to normal. -

Dover District Council Submission on Council Size

Dover District Council Submission on Council Size 8 December 2017 [This page has been intentionally left blank] Contents Section Page No. Foreword from the Chief Executive, Nadeem Aziz 3 Summary of Proposals 5 Part 1 - Introduction 6 Electoral Review 6 The Dover District 6 Shared Services 8 The Dover District Local Plan 9 Electoral Arrangements for the Dover District 9 Part 2 – Governance and Decision Making Arrangements 11 Current Governance Arrangements 11 The Executive 11 The Council 16 Other Bodies 16 Committee Arrangements 17 Delegated Decisions 18 Outside Body Appointments 19 Plans for Future Governance Arrangements 19 Committees 20 Proposed Council Size of 32 Councillors 27 Part 3 – Scrutiny Function 28 Current Arrangements 28 Future Scrutiny Arrangements 29 The Preferred Model 31 Part 4 – The Representational Role of Councillors in the Community 32 Part 5 – Comparison with Other Districts 34 Comparison with Canterbury and Shepway 35 Part 6 – Overall Conclusions on Council Size 37 Appendix 1 – Committee Functions 39 Appendix 2 – Outside Body Appointments 43 Appendix 3 – Ward Councillor Role 45 Appendix 4 – Proposed Future Governance Arrangements 47 1 | Page [This page has been intentionally left blank] 2 | Page Foreword Nadeem Aziz Chief Executive I am pleased to provide the Council’s submission on council size for consideration by the Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) as part of the preliminary stage of the Electoral Review process. You will recall that the Council had initially requested a review on council size for ‘around 35’ councillors at its meeting held on 17 May 2017. This initial position has been refined following an Extraordinary Council meeting held on 6 December 2017 and we are now asking that a council size of 32 Members be adopted. -

Christine Haggart Clerk to Ash Parish Council

Christine Haggart Environment, Planning and Clerk to Ash Parish Council (Dover District) Enforcement c/o 5 Fairview Road, Invicta House Elvington, nr Dover, County Hall Maidstone Kent Kent CT15 4EP ME14 1XX Phone: 03000 415673 Ask for: Francesca Potter Email: [email protected] 23 December 2019 BY EMAIL ONLY Dear Ms Haggart Re: Ash Parish Council Neighbourhood Development Plan - Regulation 14 Thank you for consulting Kent County Council (KCC) on the Ash Parish Neighbourhood Development Plan, in accordance with the Neighbourhood Planning (General) Regulations 2012. The County Council has reviewed the draft Neighbourhood Plan and, for ease of reference, has provided comments structured under the chapter headings and policies in the Neighbourhood Plan. Section 2: Ash Parish Now Locality and History Paragraph 24 – The text in this paragraph refers to resources held at the Ash Heritage Group. It could also usefully mention the Ash Neighbourhood Development Plan Archaeological Review that was prepared in 2018, which provides a helpful review of the archaeological history of Ash. This review is primarily drawn from the Kent Historic Environment Record, which should also be mentioned as a source of baseline evidence. Paragraph 30 - The County Council recommends that “105 Historic England building listings” is amended to read “105 Listed Buildings”. There are 789 records of archaeological sites, historic buildings and artefactual discoveries in the Parish that are not legally protected, but which nonetheless contribute to the historic character of Ash. Paragraph 32 - The historic character of the landscape is a key element of the character of Ash (particularly on the fringes of existing developments or on greenfield sites).