Bollywood Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bollywood Lens Syllabus

Bollywood's Lens on Indian Society Professor Anita Weiss INTL 448/548, Spring 2018 [email protected] Mondays, 4-7:20 pm 307 PLC; 541 346-3245 Course Syllabus Film has the ability to project powerful images of a society in ways conventional academic mediums cannot. This is particularly true in learning about India, which is home to the largest film industries in the world. This course explores images of Indian society that emerge through the medium of film. Our attention will be focused on the ways in which Indian society and history is depicted in film, critical social issues being explored through film; the depicted reality vs. the historical reality; and the powerful role of the Indian film industry in affecting social orientations and values. Course Objectives: 1. To gain an awareness of the historical background of the subcontinent and of contemporary Indian society; 2. To understand the sociocultural similarities yet significant diversity within this culture area; 3. To learn about the political and economic realities and challenges facing contemporary India and the rapid social changes the country is experiencing; 4. To learn about the Indian film industry, the largest in the world, and specifically Bollywood. Class format Professor Weiss will open each class with a short lecture on the issues which are raised in the film to be screened for that day. We will then view the selected film, followed by a short break, and then extensive in- class discussion. Given the length of most Bollywood films, we will need to fast-forward through much of the song/dance and/or fighting sequences. -

Kohram Movie Free Download in Hindi 720P Download

Kohram Movie Free Download In Hindi 720p Download 1 / 4 Kohram Movie Free Download In Hindi 720p Download 2 / 4 3 / 4 Kohram HD Amitabh Bachchan Nana Patekar Tabu H, Kohram {HD} - Amitabh Bachchan | Nana Patekar | Tabu - Hit Superhit Film by Shemaroo Download .... Kohram Full Movie Watch Online, Watch Kohram 1999 Online Full Movie Free DVDRip, Download and Watch Online Latest Hindi HD HDrip BluRay DVDscr .... Synopsis. Kohram 1999 Hindi Movie Download HD 720p Major Balbir Singh Sodhi (Amitabh Bachchan) attempts to kill the Indian Home Minister Veer Bhadra .... Khatrimaza HD Movies 300MB Movies Hd Khatrimaza.org Movies bollywood Movies ... DOWNLOAD Kohram (1999) Hindi 480p 425MB WEB HDRip MKV.. Kohram is a 1999 Indian Hindi action film directed by Mehul Kumar. It stars Amitabh Bachchan, ... Kohram. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Jump to navigation Jump to search ... Country, India. Language, Hindi. Box office, ₹13.3 crore (US$1.9 million) .... Jul 11, 2018 ... Watch Kohram: The Explosion (1999) Full Movie Online, Free Download Kohram: . FullHD 480p 720p 1080p Pc Movies Hindi Download, Mkv .... ... Movie download, Movi Kohram Dharmendra HD Mobile movie, Movi Kohram ... Dharmendra 3Gp movie, Movi Kohram Dharmendra Blu-ray 720p hd movie, .... Kohram {HD} - Amitabh Bachchan | Nana Patekar | Tabu - Hit Superhit Film. Uploaded: 12 January, 2017. By: Shemaroo. Kohraam (1991) | Dharmendra .... Jan 12, 2017 - 145 min - Uploaded by Shemaroo"Major Balbir Singh Sodhi attempts to kill the Indian Home Minister Veer Bhadra Singh but is .... May 13, 2018 ... Kohram (Ramleela) 2018 Hindi Dubbed Mkv Full Movie Download, Kohram (Ramleela) 2018 Hindi Dubbed Mkv 700 Mb Movie Download, .... Kohram {HD} - Amitabh Bachchan | Nana Patekar | Tabu - Hit Superhit Film .. -

Shah Rukh Khan from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia "SRK" Redirects Here

Shah Rukh Khan From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "SRK" redirects here. For other uses, see SRK (disambiguation). Shah Rukh Khan Shah Rukh Khan in a white shirt is interacting with the media Khan at a media event for Kolkata Knight Riders in 2012 Born Shahrukh Khan 2 November 1965 (age 50)[1] New Delhi, India[2] Residence Mumbai, Maharashtra, India Occupation Actor, producer, television presenter Years active 1988present Religion Islam Spouse(s) Gauri Khan (m. 1991) Children 3 Signature ShahRukh Khan Sgnature transparent.png Shah Rukh Khan (born Shahrukh Khan, 2 November 1965), also known as SRK, is an I ndian film actor, producer and television personality. Referred to in the media as "Baadshah of Bollywood", "King of Bollywood" or "King Khan", he has appeared in more than 80 Bollywood films. Khan has been described by Steven Zeitchik of t he Los Angeles Times as "perhaps the world's biggest movie star".[3] Khan has a significant following in Asia and the Indian diaspora worldwide. He is one of th e richest actors in the world, with an estimated net worth of US$400600 million, and his work in Bollywood has earned him numerous accolades, including 14 Filmfa re Awards. Khan started his career with appearances in several television series in the lat e 1980s. He made his Bollywood debut in 1992 with Deewana. Early in his career, Khan was recognised for portraying villainous roles in the films Darr (1993), Ba azigar (1993) and Anjaam (1994). He then rose to prominence after starring in a series of romantic films, including Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), Dil To P agal Hai (1997), Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998) and Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham.. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Spanish JOURNAL of India STUDIES

iNDIALOGS sPANISH JOURNAL OF iNDIA STUDIES Nº 1 2014 Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Editor/ Editora Felicity Hand (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona) Deputy Editors/ Editores adjuntos E. Guillermo Iglesias Díaz (Universidade de Vigo) Juan Ignacio Oliva Cruz (Universidad de La Laguna) Assistant Editors/ Editores de pruebas Eva González de Lucas (Instituto Cervantes, Kraków/Cracovia, Poland/Polonia) Maurice O’Connor (Universidad de Cádiz) Christopher Rollason (Independent Scholar) Advisory Board/ Comité Científico Ana Agud Aparicio (Universidad de Salamanca) Débora Betrisey Nadali (Universidad Complutense) Elleke Boehmer (University of Oxford, UK) Alida Carloni Franca (Universidad de Huelva) Isabel Carrera Suárez (Universidad de Oviedo) Pilar Cuder Domínguez (Universidad de Huelva) Bernd Dietz Guerrero (Universidad de Córdoba) Alberto Elena Díaz (Universidad Carlos III de Madrid) Taniya Gupta (Universidad de Granada) Belen Martín Lucas (Universidade de Vigo) Mauricio Martínez (Universidad de Los Andes y Universidad EAFIT, Bogotá, Colombia) Alejandra Moreno Álvarez (Universidad de Oviedo) Vijay Mishra (Murdoch University, Perth, Australia) Virginia Nieto Sandoval (Universidad Antonio de Nebrija) Antonia Navarro Tejero (Universidad de Córdoba) Dora Sales Salvador (Universidad Jaume I) Sunny Singh (London Metropolitan University, UK) Aruna Vasudev (Network for the Promotion of Asian Cinema NETPAC, India) Víctor Vélez (Universidad de Huelva) Layout/ Maquetación Despatx/ Office B11/144 Departament de Filologia Anglesa i Germanística Facultat -

DIPLOMARBEIT Terrorismus Im Hindi-Film

DIPLOMARBEIT Terrorismus im Hindi-Film Die Darstellung des muslimischen Terroristen als Bösewicht im indischen Mainstream-Kino,1999–2013. Anna-Franziska Steinebach angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, Januar 2015 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 317 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Betreuer: PD Mag. Dr. Claus Tieber Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Terrorismus im indischen Kontext .................................................................................. 1 1.2 Relevanz .......................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Forschungsgegenstand ..................................................................................................... 6 1.4 Hypothese ........................................................................................................................ 7 1.5 Forschungsstand .............................................................................................................. 7 1.6 Vorgehensweise und methodische Abgrenzung .............................................................. 8 2. Stereotyp ................................................................................................................................. 9 2.1 Das Stereotyp in sozialwissenschaftlichen Diskursen .................................................... -

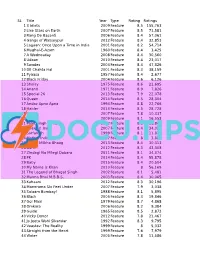

Aspirational Movie List

SL Title Year Type Rating Ratings 1 3 Idiots 2009 Feature 8.5 155,763 2 Like Stars on Earth 2007 Feature 8.5 71,581 3 Rang De Basanti 2006 Feature 8.4 57,061 4 Gangs of Wasseypur 2012 Feature 8.4 32,853 5 Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India 2001 Feature 8.2 54,714 6 Mughal-E-Azam 1960 Feature 8.4 3,425 7 A Wednesday 2008 Feature 8.4 30,560 8 Udaan 2010 Feature 8.4 23,017 9 Swades 2004 Feature 8.4 47,326 10 Dil Chahta Hai 2001 Feature 8.3 38,159 11 Pyaasa 1957 Feature 8.4 2,677 12 Black Friday 2004 Feature 8.6 6,126 13 Sholay 1975 Feature 8.6 21,695 14 Anand 1971 Feature 8.9 7,826 15 Special 26 2013 Feature 7.9 22,078 16 Queen 2014 Feature 8.5 28,304 17 Andaz Apna Apna 1994 Feature 8.8 22,766 18 Haider 2014 Feature 8.5 28,728 19 Guru 2007 Feature 7.8 10,337 20 Dev D 2009 Feature 8.1 16,553 21 Paan Singh Tomar 2012 Feature 8.3 16,849 22 Chakde! India 2007 Feature 8.4 34,024 23 Sarfarosh 1999 Feature 8.1 11,870 24 Mother India 1957 Feature 8 3,882 25 Bhaag Milkha Bhaag 2013 Feature 8.4 30,313 26 Barfi! 2012 Feature 8.3 43,308 27 Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara 2011 Feature 8.1 34,374 28 PK 2014 Feature 8.4 55,878 29 Baby 2015 Feature 8.4 20,504 30 My Name Is Khan 2010 Feature 8 56,169 31 The Legend of Bhagat Singh 2002 Feature 8.1 5,481 32 Munna Bhai M.B.B.S. -

The Female Journalist in Bollywood Middle-Class Career Woman Or Problematic National Heroine?

CRITICALviews CRITICALviews The Female Journalist in Bollywood MIDDLE-CLASS CAREER WOMAN OR PROBLEMATIC NATIONAL HEROINE? On the screen as in reality, female journalists in India have historically struggled to gain equality with their male peers. But a slew of recent Bollywood films depicting female reporters indicate that change may be afoot, as SUKHMANI KHORANA discusses. Growing up during India’s economic and communications ‘revolution’, my young mind revelled in the promise of a career in journalism that would serve both the aspirational self and the modernising nation. A role model emerged in Barkha Dutt, the LAKSHYA independent yet feminine reporter at the still-credible New Delhi Television (NDTV). I recall her fearless stint in the trenches during difficulty for career-minded women in the occasionally surface as updates on social India’s war with Pakistan in the mountains liberal West, subsequent internships at com- media, there still appears to be a plethora of Kargil (in the militancy-affected territory of mercial stations confirmed Schwartz’s views. of work opportunities in India, especially Kashmir). To my fifteen-year-old eyes, this Add to that the lack of visibility of ‘women vis-a-vis the media of the developed world. was not the beginning of embedded journal- of colour’ on Australian free-to-air televi- Moreover, as Hinglish (a mix of Hindi and ism in India. Rather, it was a milestone for sion news (barring SBS) and my journalism English) and vernacular language channels aspiring and working Indian female journal- dream was ready to shift gears and venture grow in number and importance, it is not just ists with a serious interest in hard news. -

Krrish 2006 3Gp Movie Download

Krrish 2006 3gp movie download LINK TO DOWNLOAD · Krrish () Movies Preview Koi Tumsa Nahin.3gp download. M [renuzap.podarokideal.ru] Krrish () - Pyar Ki Ek Kahani.3gp download. download 1 file. ITEM TILE download. download 16 files. MPEG4. Uplevel BACK M. Chori renuzap.podarokideal.ru Krrish 3 Video Songs Download, Krrish 3 () Hindi Movie Mp4 Video Songs Download, Krrish 3 HD Video Songs HD p p Free Download, Krrish 3 3gp Mp4 PC HD Android Mobile HD Video SongsKrrish 3 Film Full 3gp xxx mp4 video, download xnxx 3x videos, desi hot muslim girls fuck dog, indian actress katrina salman homemade 3gp sex, school renuzap.podarokideal.ru /single-post//05/30/Download-Film-Krrishgp. · Power Rangers Samurai Clash Of The Red Rangers The Movie Dual Audio p WEBRip Mbrenuzap.podarokideal.ru Krrish 3 Tamil Full Movie Free Download Mp4 krrish tamil movie download, krrish tamil movie, krrish tamil movie download kuttymovies, krrish tamil movie songs download, krrish tamil movie download tamilyogi, krrish tamil movie download tamilrockers, krrish tamil renuzap.podarokideal.ru 3 Tamil Full. Krrish 3 () Hindi BRRip Full Movie Download in Mp4 3gp HD Mp4 Bollywood movies, South Hindi Dubbed movies, Hollywood Hindi dubbed, Dual Audio, Punjabi Movies DownloadKrrish 4 Full Hindi Dubbed Movie Video Download MP4, HD MP4, Full HD, 3GP Format And Watch Krrish 4 Full Hindi Dubbed MovieKrrish Movie Free Download p BluRay HD renuzap.podarokideal.ru /06/07/KrrishFull-Movie-Download-In-Hindi-Hd. · Directed by Rakesh Roshan. With Hrithik Roshan, Priyanka Chopra, Rekha, -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee Held on 14Th, 15Th,17Th and 18Th October, 2013 Under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS)

No.F.10-01/2012-P.Arts (Pt.) Ministry of Culture P. Arts Section Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee held on 14th, 15th,17th and 18th October, 2013 under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS). The Expert Committee for the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS) met on 14th, 15th ,17thand 18th October, 2013 to consider renewal of salary grants to existing grantees and decide on the fresh applications received for salary and production grants under the Scheme, including review of certain past cases, as recommended in the earlier meeting. The meeting was chaired by Smt. Arvind Manjit Singh, Joint Secretary (Culture). A list of Expert members present in the meeting is annexed. 2. On the opening day of the meeting ie. 14th October, inaugurating the meeting, Sh. Sanjeev Mittal, Joint Secretary, introduced himself to the members of Expert Committee and while welcoming the members of the committee informed that the Ministry was putting its best efforts to promote, develop and protect culture of the country. As regards the Performing Arts Grants Scheme(earlier known as the Scheme of Financial Assistance to Professional Groups and Individuals Engaged for Specified Performing Arts Projects; Salary & Production Grants), it was apprised that despite severe financial constraints invoked by the Deptt. Of Expenditure the Ministry had ensured a provision of Rs.48 crores for the Repertory/Production Grants during the current financial year which was in fact higher than the last year’s budgetary provision. 3. Smt. Meena Balimane Sharma, Director, in her capacity as the Member-Secretary of the Expert Committee, thereafter, briefed the members about the salient features of various provisions of the relevant Scheme under which the proposals in question were required to be examined by them before giving their recommendations. -

Page 01 Feb 27.Indd

THURSDAY 27 FEBRUARY 2014 • [email protected] • www.thepeninsulaqatar.com • 4455 7741 inside Indian Indie films: CAMPUS • Qatar Academy Small, but not hosts Emirati Manga author inconsequential P | 4 P | 8-9 SCIENCE • Trying to save a rare poison frog P | 6 BOOKS • I am Malala: The struggle EGYPT’S for education SMART CARDS P | 7 HEALTH • Vegetarian diets may lower FOR BREAD blood pressure P | 11 TECHNOLOGY • BlackBerry, Motorola and Nokia search for lost glory P | 12 A device resembling a credit card swiper is revolutionising some of Learn Arabic Egypt’s politically explosive bread lines • Learn commonly used Arabic words and may help achieve the impossible and their meanings — cutting crippling food import bills. P | 13 2 PLUS | THURSDAY 27 FEBRUARY 2014 COVER STORY The financial miracle for age-old problem of Egypt’s food subsidy By Maggie Fick be bought for dollars on international markets. device resembling a Profiteers exploit the system, and credit card swiper is many people feed bread to their live- revolutionising some of stock because it is cheaper than animal Egypt’s politically explo- feed. sive bread lines and may Yet, one cash-strapped government Ahelp achieve the impossible — cutting after another has resisted attacking crippling food import bills. the problem, fearful that cutting sub- Authorities who hope to avoid pro- sidies could be political suicide. tests over subsidised loaves sold for the President Anwar Sadat triggered equivalent of one US cent have turned riots when he cut the bread subsidy in to smart cards to try to manage the 1977, while President Hosni Mubarak corrupt and wasteful bread supply faced unrest in 2008 when the rising chain that has been untouchable for price of wheat caused shortages. -

Dtp1june29final.Qxd (Page 1)

DLD‹‰‰†‰KDLD‹‰‰†‰DLD‹‰‰†‰MDLD‹‰‰†‰C A shock for Hollywood Britney admits to drug use Oops, Britney Spears has ken cocaine in the toilet of Kid Rock: Pam calling: Bebo admitted to having da- a Miami nightclub. Now, THE TIMES OF INDIA bbled in drugs, qualif- of course, the star her- Sunday, dates Durst goes global! ying that it was ‘‘a big self has chosen to co- June 29, 2003 mistake.’’ Not daring me clean. Page 7 Page 8 to actually use the A less shocking word ‘drugs’, Britn- revelation is that Brit- ey explains, ‘‘Let’s ney likes to drink — just say you reach a her favourite tipple stage in your life is ‘‘Malibu and pine- when you are curio- apple juice.’’ But us. And I was curio- she denies cheating us at one point. But on Justin Timberla- I’m way too focused ke and says she was to let anything stop ‘‘shocked’’ to see a Br- me.’’ So,was it a mis- itney-lookalike in his take? ‘‘Yes.’’ video Cry Me a River, Interestingly, not which tells the story too long back, Britney of a woman cheat- maintained that she ing on her boyfriend. OF INDIA would ‘‘sue’’ a US But then, strange things magazine which had happen when love’s lab- THANK GOD IT’S SUNDAY alleged that she had ta- our is lost. Photos: RONJOY GOGOI MANOJ KESHARWANI SOORAJ BARJATYA: THE BIG PICTURE My family was my world: My ng around, my mother decided earliest memories date back to SUNDAY SPECIAL that I needed to get married im- a home full of uncles, aunts and mediately.