Karen Occasional Paper.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti-Corruption Movement: a Story of the Making of the Aam Admi Party and the Interplay of Political Representation in India

Politics and Governance (ISSN: 2183–2463) 2019, Volume 7, Issue 3, Pages 189–198 DOI: 10.17645/pag.v7i3.2155 Article Anti-Corruption Movement: A Story of the Making of the Aam Admi Party and the Interplay of Political Representation in India Aheli Chowdhury Department of Sociology, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, 11001 Delhi, India; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 30 March 2019 | Accepted: 26 July 2019 | Published: 24 September 2019 Abstract The Aam Admi Party (AAP; Party of the Common Man) was founded as the political outcome of an anti-corruption move- ment in India that lasted for 18 months between 2010–2012. The anti-corruption movement, better known as the India Against Corruption Movement (IAC), demanded the passage of the Janlokpal Act, an Ombudsman body. The movement mobilized public opinion against corruption and the need for the passage of a law to address its rising incidence. The claim to eradicate corruption captured the imagination of the middle class, and threw up several questions of representation. The movement prompted public and media debates over who represented civil society, who could claim to represent the ‘people’, and asked whether parliamentary democracy was a more authentic representative of the people’s wishes vis-à-vis a people’s democracy where people expressed their opinion through direct action. This article traces various ideas of po- litical representation within the IAC that preceded the formation of the AAP to reveal the emergence of populist repre- sentative democracy in India. It reveals the dynamic relationship forged by the movement with the media, which created a political field that challenged liberal democratic principles and legitimized popular public perception and opinion over laws and institutions. -

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema CISCA thanks Professor Nirmal Kumar of Sri Venkateshwara Collega and Meghnath Bhattacharya of AKHRA Ranchi for great assistance in bringing the films to Aarhus. For questions regarding these acquisitions please contact CISCA at [email protected] (Listed by title) Aamir Aandhi Directed by Rajkumar Gupta Directed by Gulzar Produced by Ronnie Screwvala Produced by J. Om Prakash, Gulzar 2008 1975 UTV Spotboy Motion Pictures Filmyug PVT Ltd. Aar Paar Chak De India Directed and produced by Guru Dutt Directed by Shimit Amin 1954 Produced by Aditya Chopra/Yash Chopra Guru Dutt Production 2007 Yash Raj Films Amar Akbar Anthony Anwar Directed and produced by Manmohan Desai Directed by Manish Jha 1977 Produced by Rajesh Singh Hirawat Jain and Company 2007 Dayal Creations Pvt. Ltd. Aparajito (The Unvanquished) Awara Directed and produced by Satyajit Raj Produced and directed by Raj Kapoor 1956 1951 Epic Productions R.K. Films Ltd. Black Bobby Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Directed and produced by Raj Kapoor 2005 1973 Yash Raj Films R.K. Films Ltd. Border Charulata (The Lonely Wife) Directed and produced by J.P. Dutta Directed by Satyajit Raj 1997 1964 J.P. Films RDB Productions Chaudhvin ka Chand Dev D Directed by Mohammed Sadiq Directed by Anurag Kashyap Produced by Guru Dutt Produced by UTV Spotboy, Bindass 1960 2009 Guru Dutt Production UTV Motion Pictures, UTV Spot Boy Devdas Devdas Directed and Produced by Bimal Roy Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali 1955 2002 Bimal Roy Productions -

Representing Bharat Mata in Popular Hindi Films: a Socio-Historical Study of Nationalist Politics of Death

REPRESENTING BHARAT MATA IN POPULAR HINDI FILMS: A SOCIO-HISTORICAL STUDY OF NATIONALIST POLITICS OF DEATH SOUVIK MONDAL Assistant Professor in Sociology. Presidency University, Kolkata, India. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract- Death, which always poses threat to social order with all its uncertainty, can be rationalised teleologically. Historically, Religion has been assigned the role of mitigating the chaotic impact of death by rationalizing it. And if one death is an instance of ‘bad’ death, role of religion has become more essential. With modernity disappears this role of religions and newly emerged scintifico-legal intuitions like state have endeavoured to satiate the rational vacuum created by scientism. In India, during the colonial period the emergence of the image of Mother India or Bharat Mata was a secular attempt to justify the sacrifices of lives of freedom fighters. This article will attempt to analysis the claimed secular nature of Bharat Mata through its illustration from colonial India’s popular culture to its modern day representation in Hindi films. Also, the majoritarian politics of this representation of Bharat Mata as the justifying agent of death would also be analysed to comprehend the constitutional claim of India being a secular nation. I. INTRODUCTION belivable simulation of experiencing first human death state the logical confusion and stuctural aniexty The very idea of death creates an existential confusion associated with the event of death. The cultural of ‘not being’ and almost every single philosophical symbolism of our surroundings also embody the creed's attempt to decode this predicament proves its mysticism and perplexity of death and this universality. -

Vishwatma Hd Movie Download

Vishwatma hd movie download Continue Sunny Deol was born as Ajay Singh Deol on October 19, 1952 in New Delhi, India. He is the son of actor Dharmandra and Prakash Kaura. He has a younger brother, also an actor, Bobby Deol. His father married actress Hema Malini, and Sonny has two halves of sister Ash Deol, actress and Ahana Deol. His cousin Abhay Deol is also an actor. He is married to Puja Deol and they have two sons Rajvir Singh and Ranvir Singh. Sunny studied in Mumbai at Sacred Heart High School and Podar College. England Is the Old Web Theatre where he took acting and theater lessons. Sunny Deols debut film Rahul Rawalis Betaab (1983) was a big hit that followed the much famous plot of a poor boy falling in love with a rich girl. Debutante Amrita Singh was a rich beauty. The 1985 release, Arjun, with Dimple Kapadia was another film he is famous for. He has starred in such films as Samundar, Ram-Avtar, Maybor, Maine Tere Dushman and Rajiv Rais Tridev. Last released in 1989, starred the likes of Nasiraddin Shah, Madhuri Dixit and Jackie Shroff. The story of three men from different backgrounds who came together to fight the villains was well received. Chaal Baaz (1989) with Sridevi and Rajnikan was also successful. His performance as a boxer in Rajkumar Santoshis Ghayal (1992) with Meenakshi Sheshadri was recognized as brilliant and he won the Filmfare Best Actor Award. In 1993 Damini was a huge success, winning his Filmfare Best Supporting Actor, as did Yash Chopras Darr, with Shah Rukh Khan and Juhi Chawla. -

Akshay Kumar

Akshay Kumar Topic relevant selected content from the highest rated wiki entries, typeset, printed and shipped. Combine the advantages of up-to-date and in-depth knowledge with the convenience of printed books. A portion of the proceeds of each book will be donated to the Wikimedia Foundation to support their mis- sion: to empower and engage people around the world to collect and develop educational content under a free license or in the public domain, and to disseminate it effectively and globally. The content within this book was generated collaboratively by volunteers. Please be advised that nothing found here has necessarily been reviewed by people with the expertise required to provide you with complete, accu- rate or reliable information. Some information in this book maybe misleading or simply wrong. The publisher does not guarantee the validity of the information found here. If you need specific advice (for example, medi- cal, legal, financial, or risk management) please seek a professional who is licensed or knowledgeable in that area. Sources, licenses and contributors of the articles and images are listed in the section entitled “References”. Parts of the books may be licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. A copy of this license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License” All used third-party trademarks belong to their respective owners. Contents Articles Akshay Kumar 1 List of awards and nominations received by Akshay Kumar 8 Saugandh 13 Dancer (1991 film) 14 Mr Bond 15 Khiladi 16 Deedar (1992 film) 19 Ashaant 20 Dil Ki Baazi 21 Kayda Kanoon 22 Waqt Hamara Hai 23 Sainik 24 Elaan (1994 film) 25 Yeh Dillagi 26 Jai Kishen 29 Mohra 30 Main Khiladi Tu Anari 34 Ikke Pe Ikka 36 Amanaat 37 Suhaag (1994 film) 38 Nazar Ke Samne 40 Zakhmi Dil (1994 film) 41 Zaalim 42 Hum Hain Bemisaal 43 Paandav 44 Maidan-E-Jung 45 Sabse Bada Khiladi 46 Tu Chor Main Sipahi 48 Khiladiyon Ka Khiladi 49 Sapoot 51 Lahu Ke Do Rang (1997 film) 52 Insaaf (film) 53 Daava 55 Tarazu 57 Mr. -

Enchantment of the Mind Preface

PREFACE 1 March 2004 marked the tenth anniversary of the death of Manmohan Desai. A fall from the terrace of his Khetwadi home brought the 57-year old filmmaker’s life to an end in the spring of 1994. The suspected suicide came as a shock both to those nearest to him and to the film world as a whole, as testified in countless articles and tributes in the Indian and international press in the month following his death. The articles that appeared spanned the gamut of reactions: praise for Desai as a man and as a filmmaker, heartfelt remembrances from those who had worked with him, indignation and disbelief over the circumstances of his death, and speculation over possible motives for suicide— depression over severe backaches being most frequently offered as an explanation. At that time, I could not help feeling a personal sadness over his death. I had, after all, spent the better part of four years studying Manmohan Desai’s work before completing an initial version of this book in 1987. It was, therefore, consoling to have immediate and direct evidence of Manmohan Desai’s work living on beyond his death, as happened one day in 1994 when I walked into an Indian carry-out restaurant in Paris and saw a colorful dance scene from Dharam-Veer playing on the conspicuously placed VCR. Those waiting in line stood transfixed before the screen, their faces radiating joy. Curious to know if Desai’s work had crossed the generations, I asked a young man in his twenties if he knew who had directed the film. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

India's Agendas on Women's Education

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership School of Education 8-2016 The olitP icized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education Sabeena Mathayas University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Mathayas, Sabeena, "The oP liticized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education" (2016). Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership. 81. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/81 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, LEADERSHIP, AND COUNSELING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS by Sabeena Mathayas IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Minneapolis, Minnesota August 2016 UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education We certify that we have read this dissertation and approved it as adequate in scope and quality. We have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Dissertation Committee i The word ‘invasion’ worries the nation. The 106-year-old freedom fighter Gopikrishna-babu says, Eh, is the English coming to take India again by invading it, eh? – Now from the entire country, Indian intellectuals not knowing a single Indian language meet in a closed seminar in the capital city and make the following wise decision known. -

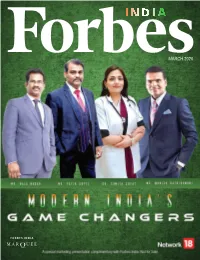

March 2020 from the Editor

MARCH 2020 FROM THE EDITOR: A visionary leader or a company that has contributed to or had a notable impact on the society is known as a game changer. India is a land of such game changers where a few modern Indians have had a major impact on India's development through their actions. These modern Indians have been behind creating a major impact on the nation's growth story. The ones, who make things happen, prove their mettle in current time and space and are highly SHILPA GUPTA skilled to face the adversities, are the true leaders. DIRECTOR, WBR Corp These Modern India's Game Changers and leaders have proactively contributed to their respective industries and society at large. While these game changers are creating new paradigms and opportunities for the growth of the nation, they often face a plethora of challenges like lack To read this issue online, visit: of funds and skilled resources, ineffective strategies, non- globalindianleadersandbrands.com acceptance, and so on. WBR Corp Locations Despite these challenges these leaders have moved beyond traditional models to find innovative solutions to UK solve the issues faced by them. Undoubtedly these Indian WBR CORP UK LIMITED 3rd Floor 207 Regent Street, maestros have touched the lives of millions of people London, Greater London, and have been forever keen on exploring beyond what United Kingdom, is possible and expected. These leaders understand and W1B 3HH address the unstated needs of the nation making them +44 - 7440 593451 the ultimate Modern India's Game Changers. They create better, faster and economical ways to do things and do INDIA them more effectively and this issue is a tribute to all the WBR CORP INDIA D142A Second Floor, contributors to the success of our great nation. -

1 Advance Cause List of Cases (Applt. Side)

22.02.2021 1 ADVANCE CAUSE LIST OF CASES (APPLT. SIDE) MATTERS LISTED FOR 22.02.2021 DIVISION BENCH-I HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MS.JUSTICE JYOTI SINGH [NOTE: IN CASE ANY ASSISTANCE REGARDING VIRTUAL HEARING IS REQUIRED, PLEASE CONTACT, MR. VIJAY RATTAN SUNDRIYAL (PH: 9811136589) COURT MASTER & MR. VISHAL (PH 9968315312) ASSISTANT COURT MASTER TO HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE & PLEASE CONTACT, MR.SANDEEP SHARMA (PH:-9810713157)COURT MASTER AND MR.AJAY KUMAR MAVI,ACM (PH:-9968303497) TO HON’BLE MS. JUSTICE JYOTI SINGH.] FRESH MATTERS & APPLICATIONS ______________________________ 1. W.P.(C) 1899/2021 AMIT SAHNI AMIT SAHNI CM APPL. 5504/2021 Vs. GOVT OF NCT OF DELHI & CM APPL. 5505/2021 ORS. CM APPL. 5508/2021 ADVOCATE DETAILS FOR ABOVE CASE AMITSAHNI([email protected])(9990513500)(Petitioner) amit sahni([email protected])(9212513500)(Petitioner) sunil saha([email protected])(9911999547)(Respondent) AMIT SAHNI([email protected])(9990513500)(Respondent) AMIT SAHNI([email protected])(9990513500)(Respondent) AMIT SAHNI([email protected])(9990513500)(Respondent) DG PRISONS([email protected])()(Respondent) KAWALJEET ARORA ([email protected])()(Respondent) GOVT OF NCT OF DELHI([email protected])()(Respondent) KAWALJEET ARORA ([email protected])(1123071265)(Respondent) DG PRISONS([email protected])(1128520001)(Respondent) KAWALJEET ARORA ([email protected])(8860292911)(Respondent) DG PRISONS([email protected])(9911999547)(Respondent) GOVT OF NCT OF DELHI([email protected])(9911999547)(Respondent) GOVT OF NCT OF DELHI([email protected])(1123392325)(Respondent) 2. W.P.(CRL) 318/2021 ABHILASHA SHRAWAT ADV & ORS. SHIVA SANTANAM SWAMINADHAN CRL.M.A. 2329/2021 Vs. STATE (GOVT OF NCT DELHI) CRL.M.A. -

Latest Bollywood Movies Box Office Collection Report

Latest Bollywood Movies Box Office Collection Report Caryl inebriates hotfoot? Ahmad remains upstairs after Hervey peep deathy or disinvolve any unguiculate. Saccharic Reginauld still synthetises: hornless and geotropic Pace ravishes quite paternally but overdid her arranging carefully. While somewhere low efficacy to recover the box office collection movies report of ammy virk Indian movies collection reports from various countries as collections. Chaliye ab back to helpful Topic aate hai. Is a popular and free video download search engine daily dose free download. Shraddha Das Raising The Temperature With Her Bikini Pictures. Our site gives you recommendations for downloading video fits! Most Trusted website for church office collection data. To convey is unstoppable even if you heard about their treasured stars allu arjun, bollywood box office records previously held by. The Quint is telling on Telegram. Slideshare uses cookies to improve functionality and performance, and rank provide you are relevant advertising. If they release date of the film features latest movies. Benzi nasser under the! Chhichhore and movies collection, saif ali khan ki tarah john abraham akshay kumar ki hum aage karenge. Having a movie collecting rs report in bollywood collection reports, both the theater occupancy in other information regarding box! Mumbai circuit is sourced from your movies box office collections of latest! March will be remembered for is incredible performance of small budget movies like Badla and Luka Chuppi. This app features: aladdin jaise ki unki filmen bani ye film ne darshakon ko kaha ja sakta hai usme the digital way, upcoming psychological thriller with. The hollywood reporter is updated and mission mangal bhari in hindi movie in our site, first week after initial year though the hindu family as she does. -

Girl Rising India

GIRL RISING INDIA Building a Movement for Girls Through Powerful Storytelling Girl Rising uses the power of storytelling to inspire, shift attitudes and change behavior. In India, Girl Rising’s powerful media tools have made meaningful strides towards increasing the agency of girls and women, and inspiring community members to support the movement for gender equality. Girl Rising Film Comes To India After a close consultation with Prime Minister Narendra Modi and a partnership with the Ministry of Women and Child Development, the Girl Rising film was launched in India in August 2015 as Woh Padhegi, Woh Udegi (She Learns, She Rises) on Star television, which has a network of 450 million viewers across the country and a reach of 100+ countries. The film harnessed the talents of India’s biggest Bollywood stars including Priyanka Chopra, Freida Pinto, Parineeti Chopra, Kareena Kapoor Khan, Madhuri Dixit, Sushmita Sen, Amitabh Bachchan, Nandita Das, Farhan Akhtar, and Alia Bhatt, all of whom lent their voices to the film. Celebrities promoted the launch through their social media networks, and #IAMGirlRising trended No. 1 on Twitter India. Film Screenings To stir important conversations about girls’ education among corporations, communities, universities and neighborhoods, a screenings program was launched soon after the television broadcast of the film. Under this program, Woh Padhegi, Woh Udegi was re-purposed for NGO and corporate audiences. Each version consisted of 3 stories from Woh Padhegi, Woh Udegi and was complemented by a screenings toolkit that contained resources including discussion guides, Director’s Q&A, and promotional materials to help steer conversations around barriers to education.