Historiographical Conversations About the Backcountry: Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Spring 2006.Qxd

Anthony Grafton History’s postmodern fates Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/daed/article-pdf/135/2/54/1829123/daed.2006.135.2.54.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 As the twenty-½rst century begins, his- in the mid-1980s to almost one thousand tory occupies a unique, but not an envi- now. But the vision of a rise in the num- able, position among the humanistic dis- ber of tenure-track jobs that William ciplines in the United States. Every time Bowen and others evoked, and that lured Clio examines her reflection in the mag- many young men and women into grad- ic mirror of public opinion, more voices uate school in the 1990s, has never mate- ring out, shouting that she is the ugliest rialized in history. The market, accord- Muse of all. High school students rate ingly, seems out of joint–almost as bad- history their most boring subject. Un- ly so as in the years around 1970, when dergraduates have fled the ½eld with production of Ph.D.s ½rst reached one the enthusiasm of rats leaving a sinking thousand or more per year just as univer- ship. Thirty years ago, some 5 percent sities and colleges went into economic of all undergraduates majored in histo- crisis. Many unemployed holders of doc- ry. Nowadays, around 2 percent do so. torates in history hold their teachers and Numbers of new Ph.D.s have risen, from universities responsible for years of op- a low of just under ½ve hundred per year pression, misery, and wasted effort that cannot be usefully reapplied in other careers.1 Anthony Grafton, a Fellow of the American Acad- Those who succeed in obtaining ten- emy since 2002, is Henry Putnam University Pro- ure-track positions, moreover, may still fessor of History at Princeton University and ½nd themselves walking a stony path. -

I^Igtorical ^Siisociation

American i^igtorical ^siisociation SEVENTY-SECOND ANNUAL MEETING NEW YORK HEADQUARTERS: HOTEL STATLER DECEMBER 28, 29, 30 Bring this program with you Extra copies 25 cents Please be certain to visit the hook exhibits The Culture of Contemporary Canada Edited by JULIAN PARK, Professor of European History and International Relations at the University of Buffalo THESE 12 objective essays comprise a lively evaluation of the young culture of Canada. Closely and realistically examined are literature, art, music, the press, theater, education, science, philosophy, the social sci ences, literary scholarship, and French-Canadian culture. The authors, specialists in their fields, point out the efforts being made to improve and consolidate Canada's culture. 419 Pages. Illus. $5.75 The American Way By DEXTER PERKINS, John L. Senior Professor in American Civilization, Cornell University PAST and contemporary aspects of American political thinking are illuminated by these informal but informative essays. Professor Perkins examines the nature and contributions of four political groups—con servatives, liberals, radicals, and socialists, pointing out that the continu ance of healthy, active moderation in American politics depends on the presence of their ideas. 148 Pages. $2.75 A Short History of New Yorh State By DAVID M.ELLIS, James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, Harry J. Carman HERE in one readable volume is concise but complete coverage of New York's complicated history from 1609 to the present. In tracing the state's transformation from a predominantly agricultural land into a rich industrial empire, four distinguished historians have drawn a full pic ture of political, economic, social, and cultural developments, giving generous attention to the important period after 1865. -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Ralph

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Ralph H. Records Collection Records, Ralph Hayden. Papers, 1871–1968. 2 feet. Professor. Magazine and journal articles (1946–1968) regarding historiography, along with a typewritten manuscript (1871–1899) by L. S. Records, entitled “The Recollections of a Cowboy of the Seventies and Eighties,” regarding the lives of cowboys and ranchers in frontier-era Kansas and in the Cherokee Strip of Oklahoma Territory, including a detailed account of Records’s participation in the land run of 1893. ___________________ Box 1 Folder 1: Beyond The American Revolutionary War, articles and excerpts from the following: Wilbur C. Abbott, Charles Francis Adams, Randolph Greenfields Adams, Charles M. Andrews, T. Jefferson Coolidge, Jr., Thomas Anburey, Clarence Walroth Alvord, C.E. Ayres, Robert E. Brown, Fred C. Bruhns, Charles A. Beard and Mary R. Beard, Benjamin Franklin, Carl Lotus Belcher, Henry Belcher, Adolph B. Benson, S.L. Blake, Charles Knowles Bolton, Catherine Drinker Bowen, Julian P. Boyd, Carl and Jessica Bridenbaugh, Sanborn C. Brown, William Hand Browne, Jane Bryce, Edmund C. Burnett, Alice M. Baldwin, Viola F. Barnes, Jacques Barzun, Carl Lotus Becker, Ruth Benedict, Charles Borgeaud, Crane Brinton, Roger Butterfield, Edwin L. Bynner, Carl Bridenbaugh Folder 2: Douglas Campbell, A.F. Pollard, G.G. Coulton, Clarence Edwin Carter, Harry J. Armen and Rexford G. Tugwell, Edward S. Corwin, R. Coupland, Earl of Cromer, Harr Alonzo Cushing, Marquis De Shastelluz, Zechariah Chafee, Jr. Mellen Chamberlain, Dora Mae Clark, Felix S. Cohen, Verner W. Crane, Thomas Carlyle, Thomas Cromwell, Arthur yon Cross, Nellis M. Crouso, Russell Davenport Wallace Evan Daview, Katherine B. -

Book Reviews and Book Notes

BOOK REVIEWS AND BOOK NOTES EDITED BY NORMAN B. WILKINSON lVe.xed and Troubled Englishmen, T590-i642. By Carl Bridenbaugh. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1968. Pp. 487. $10.00.) In this enormously erudite and lengthy volume Carl Bridenbaugh investi- gates the characters, habits, and activities of Englishmen in the half cen- tury before war erupted between King and Parliament, and during which "The First Swarming" and "The Puritan Hegira" took place. He has explored the visual remains of an earlier England, consulted a vast nunm- ber of archives, libraries, and repositories, and scrutinized the evidence afforded by literature, secular and ecclesiastical records, the Statute Book, pamphlets, tracts and sermons. Purely demographical statistics and analysis are not stressed, nor is any attempt made to compare the condition and motivation of English with other colonial peoples, though an occasional note reveals some interest in this. What has been most successfully achieved is a panorama more vivid and extensive than hitherto available, of the island inhabitants on the eve of colonization. The author's easy command of varied material and lively style make this readily and agreeably perceived and understood. Students of both English and early American history should be grateful for the series of pictures of the people in country and town; their ranks of society, health and disease, daily routine and food, community partic- ipation, and their sins against God and man. Three chapters deal with "The Rulers and the Ruled"; "The Faiths of Englishmen"; and "Educated and Cultured English." The chief concern throughout is the portraying of the vexatious and troubles besetting the everyday life of ordinary people in the early seventeenth century; purely constitutional, political and ideological controversies appear only inferentially. -

In 193X, Constance Rourke's Book American Humor Was Reviewed In

OUR LIVELY ARTS: AMERICAN CULTURE AS THEATRICAL CULTURE, 1922-1931 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Schlueter, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Thomas Postlewait, Adviser Professor Lesley Ferris Adviser Associate Professor Alan Woods Graduate Program in Theatre Copyright by Jennifer Schlueter c. 2007 ABSTRACT In the first decades of the twentieth century, critics like H.L. Mencken and Van Wyck Brooks vociferously expounded a deep and profound disenchantment with American art and culture. At a time when American popular entertainments were expanding exponentially, and at a time when European high modernism was in full flower, American culture appeared to these critics to be at best a quagmire of philistinism and at worst an oxymoron. Today there is still general agreement that American arts “came of age” or “arrived” in the 1920s, thanks in part to this flogging criticism, but also because of the powerful influence of European modernism. Yet, this assessment was not, at the time, unanimous, and its conclusions should not, I argue, be taken as foregone. In this dissertation, I present crucial case studies of Constance Rourke (1885-1941) and Gilbert Seldes (1893-1970), two astute but understudied cultural critics who saw the same popular culture denigrated by Brooks or Mencken as vibrant evidence of exactly the modern American culture they were seeking. In their writings of the 1920s and 1930s, Rourke and Seldes argued that our “lively arts” (Seldes’ formulation) of performance—vaudeville, minstrelsy, burlesque, jazz, radio, and film—contained both the roots of our own unique culture as well as the seeds of a burgeoning modernism. -

Robert C. Darnton Shelby Cullom Davis ‘30 Professor of European History Princeton University

Robert C. Darnton Shelby Cullom Davis ‘30 Professor of European History Princeton University President 1999 LIJ r t i Robert C. Darnton The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu once remarked that Robert Damton’s principal shortcoming as a scholar is that he “writes too well.” This prodigious talent, which arouses such suspicion of aristocratic pretension among social scientists in republican France, has made him nothing less than an academic folk hero in America—one who is read with equal enthusiasm and pleasure by scholars and the public at large. Darnton’ s work improbably blends a strong dose of Cartesian rationalism with healthy portions of Dickensian grit and sentiment. The result is a uniquely American synthesis of the finest traits of our British and French ancestors—a vision of the past that is at once intellectually bracing and captivatingly intimate. fascination with the making of modem Western democracies came easily to this true blue Yankee. Born in New York City on the eve of the Second World War, the son of two reporters at the New York Times, Robert Damton has always had an immediate grasp of what it means to be caught up in the fray of modem world historical events. The connection between global historical forces and the tangible lives of individuals was driven home at a early age by his father’s death in the Pacific theater during the war. Irreparable loss left him with a deep commitment to recover the experiences of people in the past. At Phillips Academy and Harvard College, his first interest was in American history. -

Changing the Narrative

Journal of Interdisciplinary History, XLVIII:3 (Winter, 2018), 313–334. Jan de Vries Changing the Narrative: The New History That Was and Is to Come In the mid-1970s, a broad range of scholars, spanning the ideological spectrum, was actively engaged in what has been called the New History. Some of the participants in this broad movement come under discussion below, but for now it is sufficient to mention the French Annales School, the American New Economic History, the British Marxist Social History, and Historical Sociology in several forms, including modernization theorists, comparative revolutions theorists, and world-systems theorists. The adherents to these different historical orientations disagreed with each other about most substantive matters. Their single point of agreement was a shared feindbegrif—the rejection of narrative history. It inspired Burke to introduce the final volume of the New Cambridge Modern History, which appeared in 1979, with the following declaration: “In the twentieth century we have seen a break with traditional narrative history, which, like the break with the traditional novel or with representational art or with classical music, is one of the important cultural discontinuities of our time.”1 Obviously, no single influence can claim full credit for this historiographical discontinuity, but the most profound factor must be the spread of an uncomfortable feeling that the narrative form greatly restricts the types of possible historical questions and feasi- ble modes of explanation. Narrative history has attached to it, like a ball and chain, the discrete, short-term historical event—l’histoire événementielle. If, by the time of Burke’s writing, several decades of Annales School preaching had done anything, it had undermined the notion that this concept should be the foundation stone of historical explanation. -

701-01 Hunter

1 History 701: Colloquium: United States to 1865 Fall 2007 Dr. Phyllis Hunter Office: 2119 Humanities Hall [email protected] “In the beginning all the world was America.” John Locke, 1688 The purpose of this colloquium is to give graduate students a knowledge of the historiographic themes and debates that structure much of the interpretation of American History up to (and in some cases beyond) 1865. Students will read and interpret several “classic” works of history as well as several books representing new issues and/or methods. The class will be run as a seminar with weekly discussions led by groups of students. Required Texts Daniel Richter, Facing East from Indian Country (Harvard, 2003) Edmund Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom Rev. ed. (Norton, 2003) David Hackett Fischer, Albion’s Seed (Oxford, 1991) Gordon Wood, Radicalism of the American Revolution (Knopf, 1993) Simon Schama, Rough Crossings (Harper Perennial, 2007) John Larson & Michael Morrison, eds. Whither the Early Republic (Penn Press, 2005) Clare Lyons, Sex among the Rabble (UNC, 2006) John Michael Vlach, Back of the Big House (UNC, 1993) Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Men, Free Labor (Oxford, 1995) Gary Gallagher, The Confederate War (Harvard, 1999) Eric Foner, New American History (Temple Univ. Press, 1997) These texts are available for purchase at the UNCG Bookstore Requirements: 2 Because this is a seminar, the main requirement is to come to class prepared with notes and questions about the reading that will enable you to participate fully in discussion. Students will take turns leading class discussion. There will be short writing assignments and a final historiographic paper. -

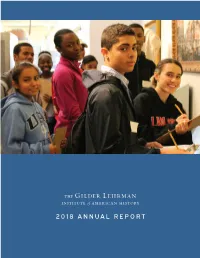

2018 Annual Report the Gilder Lehrman Institute Network in 2018

2018 ANNUAL REPORT THE GILDER LEHRMAN INSTITUTE NETWORK IN 2018 Over More than 20,000 40,000 5.6 million 750 Affiliate Schools K-12 teachers K-12 students master teachers Over Approximately 1,133 elementary, middle, 1,000 4 million and high school students historians unique website visitors entered a GLI Essay Contest More than Approximately 1,600 60,000 More than 1,011 middle and high Title I high school 428,000 educators in the school students in students in the students used 2018 Teacher GLI Saturday Hamilton Education GLI’s AP US History Seminar program Academies Program Study Guide (8% growth from 2017) 5,663 There were more than elementary, middle, and 2,114 high school teachers teachers received 455 nominated to be a professional development course enrollments in the History Teacher of the Year provided through Teaching Pace-Gilder Lehrman MA in (over 100% growth from 2017) Literacy through History American History program. OUR MISSION Students enjoy their free copies of David Blight’s Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom at the David Blight lecture in New York City, October 2018. FOUNDED IN 1994 BY RICHARD GILDER AND LEWIS E. LEHRMAN, visionaries and lifelong supporters of American history education, the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History is the leading nonprofit organization dedicated to K–12 history education while also serving the general public. The Institute’s mission is to promote the knowledge and understanding of American history through educational programs and resources. At the Institute’s core is the Gilder Lehrman Collection, one of the great archives in Amer- ican history. -

The Double Life of St. Louis Narratives of Origins and Maturity in Wade’S Urban Frontier

The Double Life of St. Louis Narratives of Origins and Maturity in Wade’s Urban Frontier ADAM ARENSON s Richard C. Wade summed up The Urban Frontier: The Rise of AWestern Cities, 1790-1830, his groundbreaking study of western urban development, he found occasion to quote William Carr Lane, St. Louis’s first mayor. In 1825, as Lane pressed the city council for the adoption of new municipal policies, he harkened back to an imagined past, a time when St. Louis “was the encamping ground of the solitary Indian trader.” Envisioning an origin story, Lane said that this first camp “became the depot and residence of many traders, under the organiza- tion of a village, and now you can see it rearing its crest in the attitude of an inspiring city.” Wade, reading across the history of Ohio Valley cities, could recognize Lane’s “history” as the rhetoric of a booster—and yet he delighted in what Lane’s story revealed as well as obscured about St. Louis’s history.1 Wade called Mayor Lane “the town’s most popular and powerful figure,” and “the West’s best student of urban affairs.”2 Such praise also __________________________ Adam Arenson is Assistant Professor of History at the University of Texas at El Paso. His book The Cultural Civil War: St. Louis and the Failures of Manifest Destiny is forthcoming. 1Richard C. Wade, The Urban Frontier: The Rise of Western Cities, 1790-1830 (Cambridge, Mass., 1959), 270, quoting Lane, St. Louis, Minutes, April 28, 1825, William Carr Lane Papers, Missouri Historical Society, St. -

Early American Reading List 2010.Pdf

Jill Lepore History Department Harvard University Early American History to 1815 Oral Examination List Spring 2010 What Is Early America? Jon Butler, Becoming America (2000) Joyce E. Chaplin, “Expansion and Exceptionalism in Early American History,” Journal of American History 89, no. 4 (2003): 1431–55 Jack P. Greene, Pursuits of Happiness: The Social Development of Early Modern British Colonies and the Formation of American Culture (1988) Richard Hofstadter, America at 1750 (1971) D. W. Meinig, The Shaping of America: Volume 1 Atlantic America, 1492-1800 (1986) Alan Taylor, American Colonies (2001) Frederick Jackson Turner, The Significance of the Frontier in American History (1893) Primary Documents Cabeza de Vaca, Narrative Richard Hakluyt, Discourse on Western Planting John Winthrop, A Modell of Christian Charity Mary Rowlandson, The Sovereignty and Goodness of God The Diary of Landon Carter Alexander Hamilton, A Gentleman’s Progress Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia Thomas Paine, Common Sense The Declaration of Independence J. Hector St. John de Crevecoeur, Letters from an American Farmer The Federalist Papers Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin The U.S. Constitution Susannah Rowson, Charlotte Temple Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America Crossings David Armitage, The British Atlantic World, 1500-1800 (2002) David Armitage, “Three Concepts of Atlantic History,” British Atlantic World (2002) Bernard Bailyn, Atlantic History: Concept and Contours (2005) Bernard Bailyn, The Peopling of British North America: An Introduction (1986) 1492 (1972) Alfred Corsby, The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of David Eltis “The Volume and Structure of the Transatlantic Slave Trade: A Reassessment,” William and Mary Quarterly (2001). -

Pulitzer Prize-Winning History Books (PDF)

PULITZER PRIZE WINNING HISTORY BOOKS The Past 50 Years 2013 Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America's Vietnam by Fredrik Logevall 2012 Malcolm X : A Life of Reinvention by Manning Marable 2011 The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery by Eric Foner 2010 Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World by Liaquat Ahamed 2009 The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family by Annette Gordon- Reed 2008 "What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848" by Daniel Walker Logevall 2007 The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation by Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff 2006 Polio: An American Story by David M. Oshinsky 2005 Washington's Crossing by David Hackett Fischer 2004 A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration by Steven Hahn 2003 An Army at Dawn: The War in North Africa, 1942-1943 by Rick Atkinson 2002 The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America by Louis Menand 2001 Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation by Joseph J. Ellis 2000 Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 by David M. Kennedy 1999 Gotham : A History of New York City to 1898 by Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace 1998 Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America's Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion by Edward J. Larson 1997 Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution by Jack N. Rakove 1996 William Cooper's Town: Power and Persuasion on the Frontier of the Early American Republic by Alan Taylor 1995 No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II by Doris Kearns Goodwin 1994 (No Award) 1993 The Radicalism of the American Revolution by Gordon S.