Champlain's Dream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gouverneur (Vermont) > Kindle

02FB1D19DC ~ Gouverneur (Vermont) > Kindle Gouverneur (V ermont) By - Reference Series Books LLC Dez 2011, 2011. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 247x190x13 mm. This item is printed on demand - Print on Demand Neuware - Quelle: Wikipedia. Seiten: 52. Kapitel: Liste der Gouverneure von Vermont, Howard Dean, Robert Stafford, Israel Smith, Richard Skinner, William Slade, William P. Dillingham, William A. Palmer, Ebenezer J. Ormsbee, John Wolcott Stewart, Cornelius P. Van Ness, Martin Chittenden, Erastus Fairbanks, George Aiken, Samuel C. Crafts, Ernest Gibson junior, Moses Robinson, Stanley C. Wilson, J. Gregory Smith, Mortimer R. Proctor, Frederick Holbrook, James Hartness, John A. Mead, John L. Barstow, Paul Brigham, Deane C. Davis, Horace F. Graham, John Mattocks, Ryland Fletcher, Josiah Grout, Percival W. Clement, Charles Manley Smith, George Whitman Hendee, John G. McCullough, Paul Dillingham, Isaac Tichenor, Ezra Butler, Samuel E. Pingree, Urban A. Woodbury, Peter T. Washburn, Carlos Coolidge, Lee E. Emerson, Harold J. Arthur, Philip H. Hoff, Charles K. Williams, Horace Eaton, Charles W. Gates, Levi K. Fuller, John B. Page, Fletcher D. Proctor, William Henry Wills, Julius Converse, Charles Paine, John S. Robinson, Stephen Royce, Franklin S. Billings, Madeleine M. Kunin, Hiland Hall, George H. Prouty, Joseph B. Johnson, Edward Curtis Smith, Silas H. Jennison, Roswell Farnham, Redfield Proctor, William... READ ONLINE [ 4.18 MB ] Reviews Completely essential read pdf. It is definitely simplistic but shocks within the 50 % of your book. Its been designed in an exceptionally straightforward way which is simply following i finished reading through this publication in which actually changed me, change the way i believe. -- Damon Friesen Completely among the finest book I have actually read through. -

General Election Results: Governor, P

1798 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 6,211 66.4% Moses Robinson [Democratic Republican] 2,805 30.0% Scattering 332 3.6% Total votes cast 9,348 33.6% 1799 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 7,454 64.2% Israel Smith [Democratic Republican] 3,915 33.7% Scattering 234 2.0% Total votes cast 11,603 100.0% 1800 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 6,444 63.4% Israel Smith [Democratic Republican] 3,339 32.9% Scattering 380 3.7% Total votes cast 10,163 100.0% 1802 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 7,823 59.8% Israel Smith [Democratic Republican] 5,085 38.8% Scattering 181 1.4% Total votes cast 13,089 100.0% 1803 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 7,940 58.0% Jonathan Robinson [Democratic Republican] 5,408 39.5% Scattering 346 2.5% Total votes cast 13,694 100.0% 1804 2 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 8,075 55.7% Jonathan Robinson [Democratic Republican] 6,184 42.7% Scattering 232 1.6% Total votes cast 14,491 100.0% 2 Totals do not include returns from 31 towns that were declared illegal. General Election Results: Governor, p. 2 of 29 1805 3 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 8,683 61.1% Jonathan Robinson [Democratic Republican] 5,054 35.6% Scattering 479 3.4% Total votes cast 14,216 100.0% 3 Totals do not include returns from 22 towns that were declared illegal. 1806 4 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 8,851 55.0% Jonathan Robinson [Democratic Republican] 6,930 43.0% Scattering 320 2.0% Total votes cast 16,101 100.0% 4 Totals do not include returns from 21 towns that were declared illegal. -

![Cornelius P. Van Ness [Democratic Republican] 11,479 Dudley Chase](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1477/cornelius-p-van-ness-democratic-republican-11-479-dudley-chase-921477.webp)

Cornelius P. Van Ness [Democratic Republican] 11,479 Dudley Chase

1823 Cornelius P. Van Ness [Democratic Republican] 11,479 85.6% Dudley Chase 1,088 8.1% Scattering 843 6.3% Total votes cast 13,410 100.0% 1824 Cornelius P. Van Ness [Democratic Republican] 13,413 85.3% Joel Doolittle 1,962 12.5% Scattering 346 2.2% Total votes cast 15,721 100.0% 1825 Cornelius P. Van Ness [Democratic Republican] 12,229 98.4% Scattering 195 1.6% Total votes cast 12,424 100.0% 1826 Ezra Butler [Democratic Republican] 8,966 63.3% Joel Doolittle 3,157 22.3% Scattering 2,037 14.4% Total votes cast 14,160 100.0% 1827 Ezra Butler [Democratic Republican] 13,699 85.2% Joel Doolittle 1,951 12.1% Scattering 433 2.7% Total votes cast 16,083 100.0% 1828 Samuel C. Crafts [National Republican] 16,285 91.9% Joel Doolittle [Jacksonian] 926 5.2% Scattering 513 2.9% Total votes cast 17,724 100.0% General Election Results: Governor, p. 6 of 29 1829 Samuel C. Crafts [National Republican] 14,325 55.8% Herman Allen [Anti-Masonic] 7,346 28.6% Joel Doolittle [Jacksonian] 3,973 15.5% Scattering 50 0.2% Total votes cast 25,694 44.2% 6 Though Allen of Burlington declined to identify himself with the party, he received the anti- masonic vote. 1830* Samuel C. Crafts [National Republican] 13,476 43.9% William A. Palmer [Anti-Masonic] 10,923 35.6% Ezra Meech [Jacksonian] 6,285 20.5% Scattering 37 0.1% Total votes cast 30,721 100.0% 1831* William A. -

Limitations of Law and History

FALL 2020 • VOL. 46, NO. 3 VERMONT BAR JOURNAL DEPARTMENTS 5 PRESIDENT’S COLUMN PURSUITS OF HAPPINESS 8 — An Interview with Mike Donofrio, Bassist RUMINATIONS 16 — Limitations of Law and History WRITE ON 24 — Past Tense: The Legal Prose of Justice Robert Larrow WHAT’S NEW 28 — Updates from the VBA “Barn, East Montpelier” by Jennifer Emens-Butler, Esq. BE WELL 35 — How to Feel in Control When Things are Out of Control 50 BOOK REVIEW 54 IN MEMORIAM 54 CLASSIFIEDS FEATURES 36 VBF Grantee Spotlight: South Royalton Legal Clinic Teri Corsones, Esq. 38 Access to Justice Campaign 41 Invisible Bars: The Collateral Consequences of Criminal Conviction Records Kassie R. Tibbott, Esq. 42 Can Lawyers Add Surcharges to Their Bills? Mark Bassingthwaighte, Esq. 43 Vermont Paralegal Organization, Inc. Celebrates 30 Years! Lucia White, VPO President 44 Justice Delayed Is Reunification Denied Hon. Howard Kalfus 48 Pro Bono Award Winner: Thomas French Mary Ashcroft, Esq. www.vtbar.org THE VERMONT BAR JOURNAL • FALL 2020 3 Advertisers Index VERMONT BAR JOURNAL ALPS .................................................................................................18 Vol. 46, No. 3 Fall 2020 BCM Environmental & Land Law, PLLC ...........................................20 Berman & Simmons ..........................................................................10 The Vermont Bar Association Biggam Fox & Skinner ........................................................................4 35-37 Court St, PO Box 100 Montpelier, Vermont 05601-0100 Caffry Law, PLLC .................................................................................6 -

701-01 Hunter

1 History 701: Colloquium: United States to 1865 Fall 2007 Dr. Phyllis Hunter Office: 2119 Humanities Hall [email protected] “In the beginning all the world was America.” John Locke, 1688 The purpose of this colloquium is to give graduate students a knowledge of the historiographic themes and debates that structure much of the interpretation of American History up to (and in some cases beyond) 1865. Students will read and interpret several “classic” works of history as well as several books representing new issues and/or methods. The class will be run as a seminar with weekly discussions led by groups of students. Required Texts Daniel Richter, Facing East from Indian Country (Harvard, 2003) Edmund Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom Rev. ed. (Norton, 2003) David Hackett Fischer, Albion’s Seed (Oxford, 1991) Gordon Wood, Radicalism of the American Revolution (Knopf, 1993) Simon Schama, Rough Crossings (Harper Perennial, 2007) John Larson & Michael Morrison, eds. Whither the Early Republic (Penn Press, 2005) Clare Lyons, Sex among the Rabble (UNC, 2006) John Michael Vlach, Back of the Big House (UNC, 1993) Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Men, Free Labor (Oxford, 1995) Gary Gallagher, The Confederate War (Harvard, 1999) Eric Foner, New American History (Temple Univ. Press, 1997) These texts are available for purchase at the UNCG Bookstore Requirements: 2 Because this is a seminar, the main requirement is to come to class prepared with notes and questions about the reading that will enable you to participate fully in discussion. Students will take turns leading class discussion. There will be short writing assignments and a final historiographic paper. -

ED350244.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 350 244 SO 022 631 AUTHOR True, Marshall, Ed.; And Others TITLE Vermont's Heritage: A Working Conferencefor Teachers. Plans, Proposals, and Needs. Proceedingsof a Conference (Burlington, Vermont, July 8-10, 1983). INSTITUTION Vermont Univ., Burlington. Center for Researchon Vermont. SPONS AGENCY Vermont Council on the Humanities and PublicIssues, Hyde Park. PUB DATE 83 NOT:, 130p.; For a related document,see SO 022 632. PUB TYPE Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cultural Education; *Curriculum Development; Educational Resources; Elementary Secondary Education; Folk Culture; Heritage Education; *Instructional Materials; Local History;*Material Development; Social Studies; *State History;Teacher Developed Materials; *Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS *Vermont ABSTRACT This document presents materials designedto help teachers in Vermont to teachmore effectively about that state and its heritage. The materials stem froma conference at which scholars spoke to Vermont teachers about theirwork and about how it might be taught. Papers presented at the conferenceare included, as well as sample lessons and units developed byteachers who attended the conference. Examples of papers includedare: "The Varieties of Vermont's Heritage: Resources forVermont Schools" (H. Nicholas Muller, III); "Vermont Folk Art" (MildredAmes and others); and "Resource Guide to Vermont StudiesMaterials" (Mary Gover and others). Three appendices alsoare included: (1) Vermont Studies Survey: A Report -

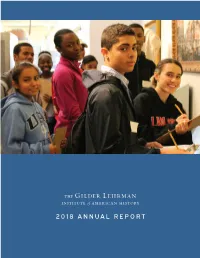

2018 Annual Report the Gilder Lehrman Institute Network in 2018

2018 ANNUAL REPORT THE GILDER LEHRMAN INSTITUTE NETWORK IN 2018 Over More than 20,000 40,000 5.6 million 750 Affiliate Schools K-12 teachers K-12 students master teachers Over Approximately 1,133 elementary, middle, 1,000 4 million and high school students historians unique website visitors entered a GLI Essay Contest More than Approximately 1,600 60,000 More than 1,011 middle and high Title I high school 428,000 educators in the school students in students in the students used 2018 Teacher GLI Saturday Hamilton Education GLI’s AP US History Seminar program Academies Program Study Guide (8% growth from 2017) 5,663 There were more than elementary, middle, and 2,114 high school teachers teachers received 455 nominated to be a professional development course enrollments in the History Teacher of the Year provided through Teaching Pace-Gilder Lehrman MA in (over 100% growth from 2017) Literacy through History American History program. OUR MISSION Students enjoy their free copies of David Blight’s Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom at the David Blight lecture in New York City, October 2018. FOUNDED IN 1994 BY RICHARD GILDER AND LEWIS E. LEHRMAN, visionaries and lifelong supporters of American history education, the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History is the leading nonprofit organization dedicated to K–12 history education while also serving the general public. The Institute’s mission is to promote the knowledge and understanding of American history through educational programs and resources. At the Institute’s core is the Gilder Lehrman Collection, one of the great archives in Amer- ican history. -

Early American Reading List 2010.Pdf

Jill Lepore History Department Harvard University Early American History to 1815 Oral Examination List Spring 2010 What Is Early America? Jon Butler, Becoming America (2000) Joyce E. Chaplin, “Expansion and Exceptionalism in Early American History,” Journal of American History 89, no. 4 (2003): 1431–55 Jack P. Greene, Pursuits of Happiness: The Social Development of Early Modern British Colonies and the Formation of American Culture (1988) Richard Hofstadter, America at 1750 (1971) D. W. Meinig, The Shaping of America: Volume 1 Atlantic America, 1492-1800 (1986) Alan Taylor, American Colonies (2001) Frederick Jackson Turner, The Significance of the Frontier in American History (1893) Primary Documents Cabeza de Vaca, Narrative Richard Hakluyt, Discourse on Western Planting John Winthrop, A Modell of Christian Charity Mary Rowlandson, The Sovereignty and Goodness of God The Diary of Landon Carter Alexander Hamilton, A Gentleman’s Progress Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia Thomas Paine, Common Sense The Declaration of Independence J. Hector St. John de Crevecoeur, Letters from an American Farmer The Federalist Papers Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin The U.S. Constitution Susannah Rowson, Charlotte Temple Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America Crossings David Armitage, The British Atlantic World, 1500-1800 (2002) David Armitage, “Three Concepts of Atlantic History,” British Atlantic World (2002) Bernard Bailyn, Atlantic History: Concept and Contours (2005) Bernard Bailyn, The Peopling of British North America: An Introduction (1986) 1492 (1972) Alfred Corsby, The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of David Eltis “The Volume and Structure of the Transatlantic Slave Trade: A Reassessment,” William and Mary Quarterly (2001). -

Pulitzer Prize-Winning History Books (PDF)

PULITZER PRIZE WINNING HISTORY BOOKS The Past 50 Years 2013 Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America's Vietnam by Fredrik Logevall 2012 Malcolm X : A Life of Reinvention by Manning Marable 2011 The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery by Eric Foner 2010 Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World by Liaquat Ahamed 2009 The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family by Annette Gordon- Reed 2008 "What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848" by Daniel Walker Logevall 2007 The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation by Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff 2006 Polio: An American Story by David M. Oshinsky 2005 Washington's Crossing by David Hackett Fischer 2004 A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration by Steven Hahn 2003 An Army at Dawn: The War in North Africa, 1942-1943 by Rick Atkinson 2002 The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America by Louis Menand 2001 Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation by Joseph J. Ellis 2000 Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 by David M. Kennedy 1999 Gotham : A History of New York City to 1898 by Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace 1998 Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America's Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion by Edward J. Larson 1997 Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution by Jack N. Rakove 1996 William Cooper's Town: Power and Persuasion on the Frontier of the Early American Republic by Alan Taylor 1995 No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II by Doris Kearns Goodwin 1994 (No Award) 1993 The Radicalism of the American Revolution by Gordon S. -

David Greenberg

DAVID GREENBERG Professor of History Professor of Journalism & Media Studies Rutgers University, The State University of New Jersey 4 Huntington Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 646.504.5071 • [email protected] Education. Columbia University, New York, NY. PhD, History. 2001. MPhil, History. 1998. MA, History. 1996. Yale University, New Haven, CT. BA, History. 1990. Summa cum laude. Phi Beta Kappa. Distinction in the major. Academic Positions. Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ. Professor, Departments of History and Journalism & Media Studies. 2016- . Associate Professor, Departments of History and Journalism & Media Studies. 2008-2016. Assistant Professor, Department of Journalism & Media Studies. 2004-2008. Appointment to the Graduate Faculty, Department of History. 2004-2008. Affiliation with Department of Political Science. Affiliation with Department of Jewish Studies. Affiliation with Eagleton Institute of Politics. Columbia University, New York, NY. Visiting Associate Professor, Department of History, Spring 2014. Yale University, New Haven, CT. Lecturer, Department of History and Political Science. 2003-04. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, Cambridge MA. Visiting Scholar. 2002-03. Columbia University, New York, NY. Lecturer, Department of History. 2001-02. Teaching Assistant, Department of History. 1996-99. Greenberg, CV, p. 2. Other Journalism and Professional Experience. Politico Magazine. Columnist and Contributing Editor, 2015- The New Republic. Contributing Editor, 2006-2014. Moderator, “The Open University” blog, 2006-07. Acting Editor (with Peter Beinart), 1996. Managing Editor, 1994-95. Reporter-researcher, 1990-91. Slate Magazine. Contributing editor and founder of “History Lesson” column, the first regular history column by a professional historian in the mainstream media. 1998-2015. Staff editor, culture section, 1996-98. The New York Times. -

Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 11-12-1992 Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Earman, Cynthia Diane, "Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830" (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOARDINGHOUSES, PARTIES AND THE CREATION OF A POLITICAL SOCIETY: WASHINGTON CITY, 1800-1830 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Cynthia Diane Earman A.B., Goucher College, 1989 December 1992 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions. -

Annual Report 2009

ANNUAL REPORT 2009 Our Mission The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History is a nonprofit organization supporting the study and love of American history through a wide range of programs and resources for students, teachers, scholars, and history enthusiasts throughout the nation. The Institute creates and works closely with history-focused schools; organizes summer seminars and development programs for teachers; produces print and digital publications and traveling exhibitions; hosts lectures by eminent historians; administers a History Teacher of the Year Award in every state and US territory; and offers national book prizes and fellowships for scholars to work in the Gilder Lehrman Collection as well as other renowned archives. Gilder Lehrman maintains two websites that serve as gateways to American history online with rich resources for educa - tors: www.gilderlehrman.org and the quarterly online journal www.historynow.org , designed specifically for K-12 teachers and students. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History Advisory Board Co-Chairmen President Executive Director Richard Gilder James G. Basker Lesley S. Herrmann Lewis E. Lehrman Joyce O. Appleby, Professor of History Emerita, Ellen V. Futter, President, American Museum University of California, Los Angeles of Natural History Edward L. Ayers, President, University of Richmond Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Alphonse Fletcher University William F. Baker, President Emeritus, Educational Professor and Director, W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for Broadcasting Corporation African and African American Research, Thomas H. Bender, University Professor of Harvard University the Humanities, New York University S. Parker Gilbert, Chairman Emeritus, Morgan Stanley Group Carol Berkin, Presidential Professor of History, Allen C. Guelzo, Henry R.