The Linguistic Character of Saadta Gaon's Translation of the Pentateuch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Discussion of the Theological Implications of Free Will in the Biblical Story of the Exodus from Egypt

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2012 A Discussion of the Theological Implications of Free Will In the Biblical Story of the Exodus From Egypt Michelle Okun Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Other Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Okun, Michelle, "A Discussion of the Theological Implications of Free Will In the Biblical Story of the Exodus From Egypt". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/194 A Discussion of the Theological Implications of Free Will In the Biblical Story of the Exodus From Egypt Michelle Okun Jewish Studies Thesis Professor Seth Sanders 12/20/11 Okun 2 Introduction Humans have always been acutely aware of their place in time and space, wondering what control they have over their lives. We ask questions such as: what do I, as an individual, control in my life? To what extent does a supreme being know what I will do? Jews and Jewish philosophers have grappled with these questions for centuries, looking to the Torah for advice and clues. Human intellect greatly influences how we view ourselves and our experiences in the context of our relationship with God. Human intellect and how it is aquired emerges first in the Genesis story, after man and woman have been created. The following passage is -

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the Freevisited Encyclopedi Ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the freevisited encyclopedi ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19 Hasidic Judaism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Sephardic pronunciation: [ħasiˈdut]; Ashkenazic , תודיסח :Hasidic Judaism (from the Hebrew pronunciation: [χaˈsidus]), meaning "piety" (or "loving-kindness"), is a branch of Orthodox Judaism that promotes spirituality through the popularization and internalization of Jewish mysticism as the fundamental aspect of the faith. It was founded in 18th-century Eastern Europe by Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov as a reaction against overly legalistic Judaism. His example began the characteristic veneration of leadership in Hasidism as embodiments and intercessors of Divinity for the followers. [1] Contrary to this, Hasidic teachings cherished the sincerity and concealed holiness of the unlettered common folk, and their equality with the scholarly elite. The emphasis on the Immanent Divine presence in everything gave new value to prayer and deeds of kindness, alongside rabbinical supremacy of study, and replaced historical mystical (kabbalistic) and ethical (musar) asceticism and admonishment with Simcha, encouragement, and daily fervor.[2] Hasidism comprises part of contemporary Haredi Judaism, alongside the previous Talmudic Lithuanian-Yeshiva approach and the Sephardi and Mizrahi traditions. Its charismatic mysticism has inspired non-Orthodox Neo-Hasidic thinkers and influenced wider modern Jewish denominations, while its scholarly thought has interested contemporary academic study. Each Hasidic Jews praying in the Hasidic dynasty follows its own principles; thus, Hasidic Judaism is not one movement but a synagogue on Yom Kippur, by collection of separate groups with some commonality. There are approximately 30 larger Hasidic Maurycy Gottlieb groups, and several hundred smaller groups. Though there is no one version of Hasidism, individual Hasidic groups often share with each other underlying philosophy, worship practices, dress (borrowed from local cultures), and songs (borrowed from local cultures). -

JEWISH SOCIETY and CULTURE I: the ANCIENT and MEDIEVAL EXPERIENCE History 506:271 / Jewish Studies 563:201 / Middle Eastern Studies 685:208

Professor Paola Tartakoff Office: 116 Miller Hall, 14 College Ave. E-mail: [email protected] JEWISH SOCIETY AND CULTURE I: THE ANCIENT AND MEDIEVAL EXPERIENCE History 506:271 / Jewish Studies 563:201 / Middle Eastern Studies 685:208 PROVISIONAL SYLLABUS Course Description: This course examines the social, intellectual, and religious life of the Jewish people from Israel's beginnings through to the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492. It starts with an overview of the history of Israel from c. 1400 B.C.E. to the end of the Babylonian Captivity. Next it turns to the Second Temple Period, focusing on Israel's encounter with Hellenism, Jewish eschatological hopes, and Jewish life under Roman rule. The course then explores the Jewish experience in the early medieval period. Topics in this section include the rise of rabbinic Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the world of the Babylonian academies, and Jewish life under Visigothic and Muslim rule. The last portion of the course examines Jewish life under Christian rule in Sepharad and Ashkenaz. It emphasizes important trends in medieval Jewish thought and spirituality and traces the evolution of medieval anti-Judaism. This course is required for majors and minors in Jewish Studies. Required Texts: • The Jews: A History, ed. John Efron et al. (Prentice Hall, 2009). ISBN: 0131786873. Available at the Rutgers University Bookstore (Ferren Mall, One Penn Plaza, 732-246-8448). $53.33. • Coursepack (CP) to be purchased at the Douglass Student Co-Op Store (57 Lipman Drive, 732-932- 9017; 1-800-929-COOP). $24.00. Recommended Text: • Hebrew Bible and New Testament in English, including the Apocrypha. -

Miracles and the Natural Order in Nahmanides*

Miracles and the Natural Order in Nahmanides* MMIRACLESIRACLES ANDAND THETHE NATURALNATURAL ORDERORDER IINN NNAHMANIDESAHMANIDES* From: Rabbi Moses Nahmanides (Ramban): Explorations in his Religious and Literary Virtuosity, ed. by Isadore Twersky (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Mass., 1983), pp. 107-128. The centrality of miracles in Nahmanides’ theology cannot escape the attention of even the most casual observer, and his doctrine of the hidden miracle exercised a particularly profound and abiding influence on subsequent Jewish thought. Nevertheless, his repeated emphasis on the miraculous—and particularly the unrestrained rhetoric of a few key passages—has served to obscure and distort his true position, which was far more moderate, nuanced and complex than both medieval and modern scholars have been led to believe. I To Nahmanides, miracles serve as the ultimate validation of all three central dogmas of Judaism: creation ex nihilo, divine knowledge, and providence (hiddush, yedi‘ah, hashgahah).1 In establishing the relationship between miracles and his first dogma, Nahmanides applies a philosophical argument in a particularly striking way. “According to the believer in the eternity of the world,” he writes, “if God wished to shorten the wing of * Some of the issues analyzed in this article were discussed in a more rudimentary form in chapters one, three, and four of my master’s essay, “Nahmanides’ Attitude Toward Secular Learning and its Bearing upon his Stance in the Maimonidean Controversy” (Columbia University, 1965), which was directed by Prof. Gerson D. Cohen. 1 Torat HaShem Temimah (henceforth THT), in Kitvei Ramban, ed. by Ch. Chavel I (Jerusalem, 1963), p. 150. On Nahmanides’ dogmas and their connection with miracles, see S. -

Death and Its Beyond in Early Judaism and Medieval Jewish Philosophy

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 3-1-2011 Death and Its Beyond in Early Judaism and Medieval Jewish Philosophy Adem Irmak University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Jewish Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Irmak, Adem, "Death and Its Beyond in Early Judaism and Medieval Jewish Philosophy" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 306. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/306 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. DEATH AND ITS BEYOND IN EARLY JUDAISM AND MEDIEVAL JEWISH PHILOSOPHY __________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts __________ by Adem Irmak March 2011 Advisor: Dr. Alison Schofield ©Copyright by Adem Irmak 2011 All Rights Reserved Author: Adem Irmak Title: DEATH AND ITS BEYOND IN EARLY JUDAISM AND MEDIEVAL JEWISH PHILOSOPHY Advisor: Dr. Alison Schofield Degree Date: March 2011 Abstract Afterlife and the concept of soul in Judaism is one of the main subjects that are discussed in the academia. There are some misassumptions related to hereafter and the fate of the soul after departing the body in Judaism. Since the Hebrew Bible does not talk about the death and afterlife clearly, some average people and some scholars claim that there is nothing relevant to the hereafter. -

SAADIA GAON When We Interrupted This Series of "Jewish Pn>F11es" Last

,,, i ,, ,7? V g Q ‘ ' ’LJ‘ S j I 28/") /rr l ' ~ - SAADIA GAON ' @ LT! -_-----'_--_ 174.7 (KEV ) V When we interrupted this series of "Jewish Pn>f11es" last April we had dealt with some of the outstanding personalities of the Rabbinic .Age,'from Hilfel 1n the first century B.C.E. to Rgv Ashi, who flourished in Babylonia about the year 400 CrE- We are nowXKg going to mAce a Jump of half a millenium to concern ourselves with a very great Jewish leader who flourished in the early part of the 10th century. This is a long Jump; and yofi will want to know, to begin with, A~pA what haypened 1n the intervening 500.years. As you can imagine, many things did happen; but you will also gather, from the fact that we gre making fine Jump, that no really outstanding person appeared in Jewry}:Er 031 during that period. 510mg Throughout this period the centre of gravity of Jewish life remained in Babylonia, to which country it'had shifted from Palestin /‘kawgn ) about 300 C.E. At the beginning of our period there were, perhaps, 303?o two million Jews in Babylonia. I said something in my last talk about the way they lived. Most of them fiere farmers, though some were artisans,_merchants and sailors. They formed a collection of mofe .. \N‘x—V or less concentrated and autonomous communities, mainly in the region of the larger cities such as Bagdad and Mahhza. Politically they were ruled by an Exilérph, or Resh Galuta. -

Provisional Syllabus

PROVISIONAL SYLLABUS CLASSICAL JEWISH PHILOSOPHY This course provides an introduction to the classical Jewish philosophical tradition. Beginning with Philo, through Saadia Gaon and Maimonides, the course will engage the works of the leading Jewish philosophers. In examining the writings of these thinkers, we will explore a number of questions, focusing on the role of language in communicating philosophical truth. Texts: There are two required books: Philo, The Works of Philo in the Yonge translation (ISBN: 0943575931). Maimonides, The Guide for the Perplexed (ISBN: 0486203514) You will also need a Bible (Old Testament). No particular translation is required. Course requirements: I cannot emphasize enough that attendance and preparation arc key to your success in the course. The class is built on our reading and discussing philosophical texts, so being part of the classroom community is essential. The Jewish holidays mean we will miss a number ofregularly scheduled classes, so it is critical that you make the commitment to being in class. This is a requirement. If you have more than four unexcused absences during the course of the semester it will affect your grade (depending on the number of absences); ten absences or more means you will not pass. We will discuss possible make- up dates Attendance docs not simply mean being physically present. You need to prepare the readings and be ready to contribute to class conversation. A brief (3-4 page) paper is due on November 1st, which will serve as your midterm. A longer (6-8 page) paper is due on December 8t 11, which will serve as your final. -

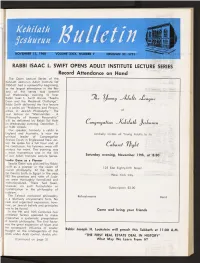

C^Onc^Rec^Ation ^J'ccllfatl Qe&Hurun N9kt

RABBI ISAAC L. SWIFT OPENS ADULT INSTITUTE LECTURE SERIES Record Attendance on Hand The Open Lecture Series of the Kehilath Jeshurun Adult Institute fof 1960-61 had a noteworthy beginning, as the largest attendance in the his¬ tory of the series was present last Wednesday evening to hear Rabbi Isaac 'L. Swift discuss "Saadia ^Jhe Gaon and the Medieval Challenge". 'L^ouncj ^dclii fad <-Heacfue Rabbi Swift delivered the first lecture in a series on "Problems and Person¬ alities in Jewish Philosophy." The of next lecture on "Maimonides - A Philosophy of Human Personality" will be delivered by Rabbi Sol Roth on Wednesday evening, December 7, C^onc^rec^ation ^J'CcLlfatl Qe&hurun at 9:00 o'clock. Our speaker, formerly a rabbi in England and Australia, is now the cordially invites all Young Adults to its spiritual leader of Congregation Ahavas Torah in Englewood New Jer¬ sey. He spoke for a full hour and, at CuLaret the conclusion, his listeners were still n9kt anxious for more. The evening was a most momentous one in the life of our Adult Institute Lecture Series. Saturday evening, November 19th, at 8:30 Saadia Gaon as a Pioneer Saadia Gaon was pictured by Rabbi Swift as a pioneer in the realm of 125 East Eighty-fifth Street Jewish philosophy. At the time of the Gaon's birth in Egypt in the year. New York City 882 the practices and rules of Juda¬ 'I ism were thoroughly formalized and institutionalized. There had been, however, no such formulation or Subscription $2.00 i crystallization in the philosophy of Judaism. -

The “Golden Age” of Jewish-Muslim Relations: Myth and Reality Mark R

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Prologue The “Golden Age” of Jewish-Muslim Relations: Myth and Reality Mark R. Cohen In the nineteenth century there was nearly universal consensus that Jews in the Islamic Middle Ages—taking al-Andalus , or Muslim Spain , as the model—lived in a “Golden Age” of Jewish-Muslim harmony,1 an interfaith utopia of tolerance and convivencia.2 It was thought that Jews min- gled freely and comfortably with Muslims, Mark R. Cohen immersed in Arabic-Islamic culture, including Professor of Near Eastern Studies at the language, poetry, philosophy, science, med- Princeton University, he holds the Khe- douri A. Zilka Professorship of Jewish icine, and the study of Scripture—a society, Civilization in the Near East. His publi- furthermore, in which Jews could and many cations include Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages did ascend to the pinnacles of political power (Princeton University Press, 1994; re- in Muslim government. This idealized picture vised edition 2008). went beyond Spain to encompass the entire Muslim world, from Baghdad to Cordova , and extended over the long centuries, bracketed by the Islamic conquests at one end and the era of Moses Maimonides (1138–1204) at the other. The idea stemmed in the fi rst instance from disappointment felt by central European Jewish historians as Emancipation-era promises of political and cultural equality remained unfulfi lled. They exploited the tolerance they ascribed to Islam to chastise their Christian neighbors for failing to rise to the standards set by non- Christian society hundreds of years earlier.3 The interfaith utopia was to a certain extent a myth; it ignored, or left unmen- tioned, the legal inferiority of the Jews and periodic outbursts of violence. -

The Aqedah at the "Crossroad": Its

Andyews University Seminary Studies, Spring-Summer 1994, Vol. 32, Nos. 1-2,29-40 CopyrightQby Andrews University Press. THE AQEDAH AT THE "CROSSROAD":ITS SIGNIFICANCE IN THE JEWISH-CHRISTIAN-MUSLIM DIALOGUE" JACQUES DOUKHAN Andrews University The memory of the Aqedah lies close to the heart of three religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. It is reflected in the liturgy of the Jews at Rosh-Ha-Shanah, of the Christians at the mass (Catholic) or holy communion (Orthodox and Protestant), and of the Muslims at the great sacrificial feast 'id al-A& ( 'id-aZ-Kabir). The same sacred story is remembered in these three traditions as an important element of their religious identity, yet the commemoration takes place at different times and represents variant meanings. In a sense, the Aqedah can be looked upon as standing at the crossroad of these three traditions as one significant sign of their common origin and also of their theological divergence. The present study examines the genesis and nature of this "crossroad." I first examine what has generated the Jewish-Christian and Jewish-Muslim controversies on the Aqedah, and what the specific character of each controversy is. Then I go back to the common source of these three traditions, namely, the Bible-and also the Qur'Zn for the Islamic tradition. This is in order to probe and/or enrich the lessons that can be learned from the controversies. The purpose of this study is modest. I will not enter into all the rich nuances of texts, traditions, and debates. Rather, I will take notice of the significant trends that relate to the Jewish-Christian and Jewish- Muslim encounters, in order to discover as far as possible the mechanisms involved, and also to serve as a basis for suggesting lessons which I believe we can learn from both the historical and present-day dialogue. -

1 Sermon by Dr. Jordan Paper Yom Kippur Morning

Sermon by Dr. Jordan Paper Yom Kippur Morning (Wednesday, September 19, 2018) WHY DO WE CELEBRATE THE HIGH HOLIDAYS? Corresponding with Rabbi Goldberg a year ago, I made some comments about the High Holidays. She suggested I give a sermon here the following year. So here I am. When I last gave a sermon in 1961, I was thrown out of a theological school for heresy. I do so now with some misgiving; I hope you checked your stones at the door. The huge sanctuary of the Orthodox synagogue in Baltimore my family went to before I left for college was virtually empty most of the year, but during the High Holidays, not only was it filled to capacity, but so were the auditorium and social hall which had ancillary services. This continues to be the situation today for many synagogues and temples. Why? Is Judaism a religion acknowledged by most of its adherents but ten days out of the year? And why these ten days? Historically, the High Holidays, as presently understood, are latecomers to the schedule of Jewish festivals. The High Holidays came to the fore Post-Diaspora when Jews in Europe began to suffer from mass murder and expulsions by Christians. The High Holidays came to be known as the Days of Awe, when the books of life and death were opened, and God’s Chosen People were judged by God as to how much they will suffer as punishment for their sinning in the previous year. My earliest memory of the High Holidays is going with my father to the water’s edge of a nearby reservoir and with him throwing pebbles from our pockets into the water to symbolize throwing away our sins (tashlikh). -

Transliteration-Guid

WELCOME Welcome to the Huntington Jewish Center and our Shabbat Services. These transliterations are offered as a regular part of our Siddur (prayerbook) so that all persons attending services at the Huntington Jewish Center may enjoy the beauty of the prayers and participate to the fullest. For those who may not be familiar with our synagogue or with our services, we include introductory material on both. Our goal is to provide an opportunity for each person to participate in a manner that affords a genuine spiritual experience. According to Jewish law, one may pray in any language. Although many congregations recite much of the liturgy in English, our own service is conducted almost entirely in Hebrew. A worshiper can experience tremendous emotional satisfaction when s/he repeats a prayer in the same language used by his/her ancestors. The Hebrew language links the Jews of all nations to one another and to their common heritage. The use of Hebrew also provides a stimulus to study the language of the Bible. This document transliterates everything spoken aloud by the congregation during the service. While this Guide is designed to answer some of the most frequently asked questions about the synagogue and our service, it cannot possibly anticipate everything. Do not hesitate to approach our Rabbi, Cantor, or regular worshipers with your questions following services. HISTORY In the late nineteenth century, services were held in the homes of the few Jewish families who lived in the Town of Huntington. In 1906, a small group of Jews organized the "Brotherhood of Jewish Men in Huntington," and in 1907 the group incorporated as the Huntington Hebrew Congregation.