Massimo Tinazzi[*]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carta E Colore Per La Ricorrenza Del 150° Anniversario Dell'unità D'italia

Carta e colore per la ricorrenza del 150° Anniversario dell’Unità d’Italia di Anna Onesti Di tre colori - carta e colore per la ricorrenza del 150° Anniversario dell’Unità d’Italia Installazione ideata e realizzata da Anna Onesti con la collaborazione di Fabrizio Di Pietro Testi di Paolo Di Paolo e Alberto Boatto Roma, 23 marzo - 1 maggio 2011, Istituto Nazionale per la Grafica, Dirigente Maria Antonella Fusco In occasione dei festeggiamenti per il 150° anniversario dell’Unità d’Italia grazie al contributo congiunto dei due Istituti Italiani di Cultura siamo lieti di presentare, per la prima volta in Australia, le 150 lanterne di Anna Onesti. Lanterne di tre colori fatte a Melbourne, 22 agosto-16 settembre 2011, Istituto Italiano di Cultura, mano, delicate, leggere eppure così evocative e potenti nel loro rammentare agli italiani Direttore Stefano Fossati in Italia e a tutti quelli che si sono stabiliti altrove nel mondo l‘Unita` del nostro paese. Sydney, 29 agosto-23 settembre 2011, Istituto Italiano di Cultura, Gli Istituti Italiani di Cultura di Melbourne e Sydney, si augurano che gli italiani Direttore Alessandra Bertini d’Australia possano vivere una grande emozione alla luce delle 150 lanterne e sentirsi parte di un paese d’origine dal quale hanno saputo trapiantare valori e conoscenza riuscendo ad affermare e a far riconoscere l’identita` italiana in ogni ambito sociale, culturale, artistico, economico, politico e scientifico. Edizione italiana della mostra Commissario della mostra: Rita Bernini We are pleased to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the unification of Italy by Grafica e comunicazione: Marina Ventura presenting for the first time in Australia, thanks to the mutual effort and contribution of Laboratori e didattica: Gabriella Bocconi the two Italian Institutes of Culture, the 150 lanterns by Anna Onesti. -

Magnetothermal Multiplexing for Biomedical Applications

Magnetothermal Multiplexing for Biomedical Applications by Michael G. Christiansen B.S. Physics, Arizona State University, 2012 Submitted to the Department of Materials Science and Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2017 © 2017 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved Signature of Author………………………………………………………………………………… Department of Materials Science and Engineering May 25, 2017 Certified by………………………………………………………………………………………… Polina Anikeeva Professor of Materials Science and Engineering Thesis Advisor Certified by………………………………………………………………………………………… Donald R. Sadoway Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students 1 Magnetothermal Multiplexing for Biomedical Applications by Michael G. Christiansen Submitted tot eh Department of Materials Science and Engineering on May 25, 2017 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Materials Science and Engineering ABSTRACT Research on biomedical applications of magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) has increasingly sought to demonstrate noninvasive actuation of cellular processes and material responses using heat dissipated in the presence of an alternating magnetic field (AMF). By modeling the dependence of hysteresis losses on AMF amplitude and constraining AMF conditions to be physiologically suitable, it can be shown that MNPs exhibit uniquely optimal driving conditions that depend on controllable material properties such as magnetic anisotropy, magnetization, and particle volume. “Magnetothermal multiplexing,” which relies on selecting materials with substantially distinct optimal AMF conditions, enables the selective heating of different kinds of collocated MNPs by applying different AMF parameters. This effect has the potential to extend the functionality of a variety of emerging techniques with mechanisms that rely on bulk or nanoscale heating of MNPs. -

ARTIFICIAL MATERIALS for NOVEL WAVE PHENOMENA Metamaterials 2019

ROME, 16-21 SEPTEMBER 2019 META MATE RIALS 13TH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS ON ARTIFICIAL MATERIALS FOR NOVEL WAVE PHENOMENA Metamaterials 2019 Proceedings In this edition, there are no USB sticks for the distribution of the proceedings. The proceedings can be downloaded as part of a zip file using the following link: 02 President Message 03 Preface congress2019.metamorphose-vi.org/proceedings2019 04 Welcome Message To browse the Metamaterials’19 proceedings, please open “Booklet.pdf” that will open the main file of the 06 Program at a Glance proceedings. By clicking the papers titles you will be forwarded to the specified .pdf file of the papers. Please 08 Monday note that, although all the submitted contributions 34 Tuesday are listed in the proceedings, only the ones satisfying requirements in terms of paper template and copyright 58 Wednesday form have a direct link to the corresponding full papers. 82 Thursday 108 Student paper competition 109 European School on Metamaterials Quick download for tablets and other mobile devices (370 MB) 110 Social Events 112 Workshop 114 Organizers 116 Map: Crowne Plaza - St. Peter’s 118 Map to the Metro 16- 21 September 2019 in Rome, Italy 1 President Message Preface It is a great honor and pleasure for me to serve the Virtual On behalf of the Technical Program Committee (TPC), Institute for Artificial Electromagnetic Materials and it is my great pleasure to welcome you to the 2019 edition Metamaterials (METAMORPHOSE VI) as the new President. of the Metamaterials Congress and to outline its technical Our institute spun off several years ago, when I was still a program. -

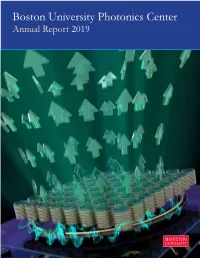

Boston University Photonics Center Annual Report 2019 the Above Image Is an Overview of MEMS Mirror Design

Boston University Photonics Center Annual Report 2019 The above image is an overview of MEMS mirror design. The image, featuring Professor David Bishop’s research, is a false color SEM image of the MEMS magnet mirror, comprised of four bimorphs that lift a polysilicon platform off the substrate. A 250 μm cubed N52 magnet is attached to the platform using a custom pick and place micro-gluing technique and a gold plated mirror is glued on top of the magnet using the same gluing technique. (Source: Reprinted with permission from © The Optical Society. C. Pollock, J. Javor, A. Stange, L. K. Barrett, and D. J. Bishop, “Extreme angle, tip-tilt MEMS micromirror enabling full-hemispheric, quasi-static optical coverage,” Optics Express, 2019, 27(11), 15318-15326.) Front cover image: Coupled nonlinear metamaterials, featuring a self-adaptive or intelligent response, serve to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio of magnetic resonance imaging by more than tenfold. (Source: X. Zhao, G. Duan, K. Wu, S.W. Anderson, and X. Zhang, “Intelligent metamaterials based on nonlinearity for magnetic resonance imaging,” Advanced Materials, 2019, 31(49): 1905461. Copyright Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. Reproduced with permission.) Letter from the Director THIS ANNUAL REPORT summarizes activities of the Boston University Photonics Center for the 2018-2019 academic year. In it, you will find quantitative and descriptive information regarding our photonics programs in education, interdisciplinary research, business innovation, and technology development. Located at the heart of Boston University’s urban campus, the Photonics Center is an interdisciplinary hub for education, research, scholarship, innovation, and technology development associated with practical uses of light. -

Volume VI 1988 NINETEENTH-CENTUKY ITALIAN

Volume VI 1988 NINETEENTH-CENTUKY ITALIAN OPERA IN THE CONTEMPORARY PRESS (PART I) Papers from Bologna: the Fourteenth Congress of the International Musicological Society (1987) Introduction H. Robert Cohen (College Park) Marcello Conati (Parma) Italian Opera and the English Press, 1836-1856 Leanne Langley (London) Zur Beurteilung der italienischen Oper in Christoph-Hellmut Mahling 11 der deutschsprachigen Presse zwischen (Mainz) 1815 und 1825 Italian Opera Premieres and Revivals Zoltán Roman 16 in the Hungarian Press, 1864-1894 (Calgary) Nineteenth-Century Italian Opera as Gerald Seaman 21 seen in the Contemporary Russian Press (Auckland) PERIODICA MUSICA Published jointly by: EDITORS Center for Studies in Nineteenth- H. Robert Cohen Century Music, University of Donald Gislason Maryland at College Park, U.S.A. Peter Loeffler Zoltán Roman Centre international de recherche sur la presse musicale, Conservatorio EDITORIAL BOARD di musica "Arrigo Boito," Parma- Comune di Colorno, Italy H. Robert Cohen Marcello Conati MPM operates under the auspices Zoltán Roman of the International Musícological Society and the International B USINES S MANAGER Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres Gaétan Martel ISSN 0822-7594 ©Copyright 1990, The University of Maryland at College Park INTRODUCTION The Fourteenth Congress of the International Musicological Society was held in Bologna, Italy (with additional sessions in Parma and Ferrara) from 27 August to 1 September 1987. Two congress sessions were organized under the auspices of the Repertoire International de la Presse Musicale by H. Robert Cohen and Marcello Conati. The second, which took place in Parma, in the Sala Verdi of the Conservatorio "Arrigo Boito " on Sunday, 30 August from 1 lh30 to 13h, offered an extensive demonstra tion of the computer programs and laser printing techniques developed for the production of RIPM volumes at the Center for Studies in Nineteenth-Century Music of the University of Maryland at College Park. -

LE MIE MEMORIE ARTISTICHE Giovanni Pacini

LE MIE MEMORIE ARTISTICHE Giovanni Pacini English translation: Adriaan van der Tang, October 2011 1 2 GIOVANNI PACINI: LE MIE MEMORIE ARTISTICHE PREFACE Pacini’s autobiography Le mie memorie artistiche has been published in several editions. For the present translation the original text has been used, consisting of 148 pages and published in 1865 by G.G. Guidi. In 1872 E. Sinimberghi in Rome published Le mie memorie artistiche di Giovanni Pacini, continuate dall’avvocato Filippo Cicconetti. The edition usually referred to was published in 1875 by Le Monnier in Florence under the title Le mie memorie artistiche: edite ed inedite, edited by Ferdinando Magnani. The first 127 pages contain the complete text of the original edition of 1865 – albeit with a different page numbering – extended with the section ‘inedite’ of 96 pages, containing notes Pacini made after publication of the 1865-edition, beginning with three ‘omissioni’. This 1875- edition covers the years as from 1864 and describes Pacini’s involvement with performances of some of his operas in several minor Italian theatres. His intensive supervision at the first performances in 1867 of Don Diego di Mendoza and Berta di Varnol was described as well, as were the executions of several of his cantatas, among which the cantata Pacini wrote for the unveiling of the Rossini- monument in Pesaro, his oratorios, masses and instrumental works. Furthermore he wrote about the countless initiatives he developed, such as the repatriation of Bellini’s remains to Catania and the erection of a monument in Arezzo in honour of the great poet Guido Monaco, much adored by him. -

The Demon Haunted World

THE DEMON- HAUNTED WORLD Science as a Candle in the Dark CARL SAGAN BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK Preface MY TEACHERS It was a blustery fall day in 1939. In the streets outside the apartment building, fallen leaves were swirling in little whirlwinds, each with a life of its own. It was good to be inside and warm and safe, with my mother preparing dinner in the next room. In our apartment there were no older kids who picked on you for no reason. Just the week be- fore, I had been in a fight—I can't remember, after all these years, who it was with; maybe it was Snoony Agata from the third floor— and, after a wild swing, I found I had put my fist through the plate glass window of Schechter's drug store. Mr. Schechter was solicitous: "It's all right, I'm insured," he said as he put some unbelievably painful antiseptic on my wrist. My mother took me to the doctor whose office was on the ground floor of our building. With a pair of tweezers, he pulled out a fragment of glass. Using needle and thread, he sewed two stitches. "Two stitches!" my father had repeated later that night. He knew about stitches, because he was a cutter in the garment industry; his job was to use a very scary power saw to cut out patterns—backs, say, or sleeves for ladies' coats and suits—from an enormous stack of cloth. Then the patterns were conveyed to endless rows of women sitting at sewing machines. -

The Birth of an Opera

THE BIRTH OF AN OPERA FIFTEEN MASTERPIECES from POPPEA TO WOZZECK Michael Rose IV • %'V • Norton & Company New York London Il Barbiere di Siviglia H E FIRST PERFORMANCE of Rossini's Barber was one of the great fiascos of operatic history. Yet only eight months earlier its composer had taken the first big step in what was to be the most daz- zling operatic career of the early nineteenth century. When Gioacchino Rossini arrived in Naples on 27 June 1815, he was twenty-three years old, he had fourteen operas to his credit, and he had never been this far from home in his life. Born in Pesaro and brought up in Bologna, his early successes had been largely confined to Venice and Milan, and the political divisions of the peninsula, recently reinstated after the Napoleonic interregnum, imposed at least two national borders between the Hapsburg regions of Lombardy and Venetia and the Bour- bon Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. But the Italian passion for opera had no respect for political frontiers and already Rossini was being spoken of across Italy as the latest operatic phenomenon. Since Naples had been for a century and a half one of the most important, perhaps the most influen- tial, of Italian centres of operatic activity, the appointment of this stripling from the north as director of its royal theatres raised eager anticipation (and not a few eyebrows) as well as opening a new chapter in Rossini's life. But Italian opera in the early nineteenth century was a cutthroat business. The Neapolitan contract did not tie him exclusively to Naples, and now that he had freed himself from the Venice-Milan axis of earlier years, Rossini was keen to exploit the new possibilities of his position. -

Quantum Model of Ferrofluid Motion

Quantum Model of Ferrofluid Motion Ferrofluids, with their mesmeric display of shape-shifting spikes, are a favorite exhibit in science shows. These eye-catching examples of magnetic fields in action could become even more dramatic through computational work that captures their motion. [37] Case Western Reserve University researchers are working to change that. They have pioneered a new approach called Magnetic Resonance Fingerprinting, which uses more sensitive scanning techniques that they expect could detect whether treatments are working after just one dose of chemo. [36] The standard approach to building a quantum computer with majoranas as building blocks is to convert them into qubits. However, a promising application of quantum computing—quantum chemistry—would require these qubits to be converted again into so-called fermions. [35] Scientists have shown how an optical chip can simulate the motion of atoms within molecules at the quantum level, which could lead to better ways of creating chemicals for use as pharmaceuticals. [34] Chinese scientists Xianmin Jin and his colleagues from Shanghai Jiao Tong University have successfully fabricated the largest-scaled quantum chip and demonstrated the first two-dimensional quantum walks of single photons in real spatial space, which may provide a powerful platform to boost analog quantum computing for quantum supremacy. [33] To address this technology gap, a team of engineers from the National University of Singapore (NUS) has developed an innovative microchip, named BATLESS, that can continue to operate even when the battery runs out of energy. [32] Stanford researchers have developed a water-based battery that could provide a cheap way to store wind or solar energy generated when the sun is shining and wind is blowing so it can be fed back into the electric grid and be redistributed when demand is high. -

Carlo Matteucci and the Legacy of Luigi Galvani

Archives Italiennes de Biologie, 149 (Suppl.): 3-9, 2011. Carlo Matteucci and the legacy of Luigi Galvani M. BRESADOLA Department of Humanities and Neuroscience Center, University of Ferrara, and National Institute of Neuroscience, Italy A bstract Carlo Matteucci (1811-1868) is considered one of the founders of electrophysiology, thanks to his research on electric fish, nerve conduction, and muscular contraction. In this essay Matteucci’s early investigation into life pro- cesses is discussed in the context of the debates on Galvanism, a new scientific field inaugurated by the discovery of animal electricity made by Luigi Galvani in the 1790s. Matteucci rejected both a “physicalist” and a “vitalist” interpretation of the phenomena of Galvanism, adopting instead the same view which had guided Galvani in his research on animal electricity. In this regard, Matteucci can be considered the true scientific heir of Galvani. Key words Matteucci, Carlo • Galvani, Luigi • Galvanism • History of electrophysiology Introduction of Moruzzi’s article; instead, I shall focus on some minor works which Matteucci published in the early In an article published in 1964, which still remains 1830s, in the period that preceded his major discov- the most relevant study of Carlo Matteucci’s sci- eries. My aim is to reconstruct the context in which entific work, Giuseppe Moruzzi claimed that “the Matteucci’s electrophysiological research began, electrophysiological work to which [Matteucci] owes and to identify some interests and motives which imperishable fame begins in 1836” (Moruzzi, 1964; guided Matteucci in his scientific investigation. To English translation in Moruzzi, 1996, p. 70). It was this end I shall examine the content of two papers in that year, in fact, that Matteucci identified the ner- which Matteucci published in 1830 and which vous centres responsible for the electrical discharge concerned some phenomena that were included in of Torpedo. -

THE JOURNAL of the ACOUSTICAL SOCIETY of AMERICA 170Th Meeting: Acoustical Society of America 138, No

The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America Vol. 138, No. 3, Pt. 2 of 2, September 2015 www.acousticalsociety.org 170th Meeting Acoustical Society of America Hyatt Regency Jacksonville Riverfront Hotel Jacksonville, Florida 2–6 November 2015 Table of Contents on p. A5 Published by the Acoustical Society of America through AIP Publishing LLC www.pcb.com/acoustics Booth #5 Come See Us at the ASA Exhibit Prepolarized Free-field Microphone Model 378B02 IEC 61094-4 compliant test and measurement microphone for audible range applications PERFORMANCE NOT JUST A MICROPHONE Inside every microphone is 40 years of sensor design and UNBEATABLE PRICE manufacturing expertise. Exceeding all expectations, our price, 24/7 TECH SUPPORT support, warranty and delivery are unmatched. BEST WARRANTY FAST SHIPMENT Toll Free in USA 800-828-8840 E-mail [email protected] Website www.pcb.com www.pcb.com/ShopSensors THE JOURNAL OF THE ACOUSTICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA ISSN: 0001-4966 Periodicals Postage Paid at Postmaster: If undeliverable, send notice on Form 3579 to: CODEN: JASMAN Huntington Station, NY and ACOUSTICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA Additional Mailing Offices 1305 Walt Whitman Road, Suite 300, Melville, NY 11747-4300 SAVE TIME AT EVERY STAGE FROM MEASUREMENT THROUGH TO REPORT FOR GOOD MEASURE Taking accurate acoustic measurements is critical – but not everything. You also need to efficiently document and report on what you’re doing to finish a project. Introducing the new Measurement Partner, a suite of innovative solutions that supports customers through every step of the measurement process. Take remote measurements with its Wi-Fi-enabled sound level meters so sound fields aren’t disturbed. -

BARBER Guide Updated 10.10.13

VICTOR DeRENZI, Artistic Director RICHARD RUSSELL, Executive Director Exploration in Opera Teacher Resource Guide - 2014 Winter Festival Season The Barber of Seville By Gioachino Rossini Table of Contents The Opera The Cast ...................................................................................................... 1 The Story ...................................................................................................... 2-3 The Composer ............................................................................................. 4 The First Performance ................................................................................. 5-6 Listening and Viewing .................................................................................. 6 The History Timeline ....................................................................................................... 7-8 The City of Seville ....................................................................................... 9-10 The History of Barbering ............................................................................. 11-13 Beaumarchais and Barber ............................................................................ 14-18 In The News ................................................................................................ 19-21 All About Opera What to Expect at the Opera ....................................................................... 22 Opera Terms ..............................................................................................