Research Bulletins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magnetothermal Multiplexing for Biomedical Applications

Magnetothermal Multiplexing for Biomedical Applications by Michael G. Christiansen B.S. Physics, Arizona State University, 2012 Submitted to the Department of Materials Science and Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2017 © 2017 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved Signature of Author………………………………………………………………………………… Department of Materials Science and Engineering May 25, 2017 Certified by………………………………………………………………………………………… Polina Anikeeva Professor of Materials Science and Engineering Thesis Advisor Certified by………………………………………………………………………………………… Donald R. Sadoway Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students 1 Magnetothermal Multiplexing for Biomedical Applications by Michael G. Christiansen Submitted tot eh Department of Materials Science and Engineering on May 25, 2017 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Materials Science and Engineering ABSTRACT Research on biomedical applications of magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) has increasingly sought to demonstrate noninvasive actuation of cellular processes and material responses using heat dissipated in the presence of an alternating magnetic field (AMF). By modeling the dependence of hysteresis losses on AMF amplitude and constraining AMF conditions to be physiologically suitable, it can be shown that MNPs exhibit uniquely optimal driving conditions that depend on controllable material properties such as magnetic anisotropy, magnetization, and particle volume. “Magnetothermal multiplexing,” which relies on selecting materials with substantially distinct optimal AMF conditions, enables the selective heating of different kinds of collocated MNPs by applying different AMF parameters. This effect has the potential to extend the functionality of a variety of emerging techniques with mechanisms that rely on bulk or nanoscale heating of MNPs. -

ARTIFICIAL MATERIALS for NOVEL WAVE PHENOMENA Metamaterials 2019

ROME, 16-21 SEPTEMBER 2019 META MATE RIALS 13TH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS ON ARTIFICIAL MATERIALS FOR NOVEL WAVE PHENOMENA Metamaterials 2019 Proceedings In this edition, there are no USB sticks for the distribution of the proceedings. The proceedings can be downloaded as part of a zip file using the following link: 02 President Message 03 Preface congress2019.metamorphose-vi.org/proceedings2019 04 Welcome Message To browse the Metamaterials’19 proceedings, please open “Booklet.pdf” that will open the main file of the 06 Program at a Glance proceedings. By clicking the papers titles you will be forwarded to the specified .pdf file of the papers. Please 08 Monday note that, although all the submitted contributions 34 Tuesday are listed in the proceedings, only the ones satisfying requirements in terms of paper template and copyright 58 Wednesday form have a direct link to the corresponding full papers. 82 Thursday 108 Student paper competition 109 European School on Metamaterials Quick download for tablets and other mobile devices (370 MB) 110 Social Events 112 Workshop 114 Organizers 116 Map: Crowne Plaza - St. Peter’s 118 Map to the Metro 16- 21 September 2019 in Rome, Italy 1 President Message Preface It is a great honor and pleasure for me to serve the Virtual On behalf of the Technical Program Committee (TPC), Institute for Artificial Electromagnetic Materials and it is my great pleasure to welcome you to the 2019 edition Metamaterials (METAMORPHOSE VI) as the new President. of the Metamaterials Congress and to outline its technical Our institute spun off several years ago, when I was still a program. -

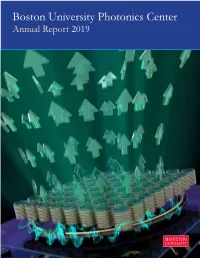

Boston University Photonics Center Annual Report 2019 the Above Image Is an Overview of MEMS Mirror Design

Boston University Photonics Center Annual Report 2019 The above image is an overview of MEMS mirror design. The image, featuring Professor David Bishop’s research, is a false color SEM image of the MEMS magnet mirror, comprised of four bimorphs that lift a polysilicon platform off the substrate. A 250 μm cubed N52 magnet is attached to the platform using a custom pick and place micro-gluing technique and a gold plated mirror is glued on top of the magnet using the same gluing technique. (Source: Reprinted with permission from © The Optical Society. C. Pollock, J. Javor, A. Stange, L. K. Barrett, and D. J. Bishop, “Extreme angle, tip-tilt MEMS micromirror enabling full-hemispheric, quasi-static optical coverage,” Optics Express, 2019, 27(11), 15318-15326.) Front cover image: Coupled nonlinear metamaterials, featuring a self-adaptive or intelligent response, serve to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio of magnetic resonance imaging by more than tenfold. (Source: X. Zhao, G. Duan, K. Wu, S.W. Anderson, and X. Zhang, “Intelligent metamaterials based on nonlinearity for magnetic resonance imaging,” Advanced Materials, 2019, 31(49): 1905461. Copyright Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. Reproduced with permission.) Letter from the Director THIS ANNUAL REPORT summarizes activities of the Boston University Photonics Center for the 2018-2019 academic year. In it, you will find quantitative and descriptive information regarding our photonics programs in education, interdisciplinary research, business innovation, and technology development. Located at the heart of Boston University’s urban campus, the Photonics Center is an interdisciplinary hub for education, research, scholarship, innovation, and technology development associated with practical uses of light. -

The Demon Haunted World

THE DEMON- HAUNTED WORLD Science as a Candle in the Dark CARL SAGAN BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK Preface MY TEACHERS It was a blustery fall day in 1939. In the streets outside the apartment building, fallen leaves were swirling in little whirlwinds, each with a life of its own. It was good to be inside and warm and safe, with my mother preparing dinner in the next room. In our apartment there were no older kids who picked on you for no reason. Just the week be- fore, I had been in a fight—I can't remember, after all these years, who it was with; maybe it was Snoony Agata from the third floor— and, after a wild swing, I found I had put my fist through the plate glass window of Schechter's drug store. Mr. Schechter was solicitous: "It's all right, I'm insured," he said as he put some unbelievably painful antiseptic on my wrist. My mother took me to the doctor whose office was on the ground floor of our building. With a pair of tweezers, he pulled out a fragment of glass. Using needle and thread, he sewed two stitches. "Two stitches!" my father had repeated later that night. He knew about stitches, because he was a cutter in the garment industry; his job was to use a very scary power saw to cut out patterns—backs, say, or sleeves for ladies' coats and suits—from an enormous stack of cloth. Then the patterns were conveyed to endless rows of women sitting at sewing machines. -

Quantum Model of Ferrofluid Motion

Quantum Model of Ferrofluid Motion Ferrofluids, with their mesmeric display of shape-shifting spikes, are a favorite exhibit in science shows. These eye-catching examples of magnetic fields in action could become even more dramatic through computational work that captures their motion. [37] Case Western Reserve University researchers are working to change that. They have pioneered a new approach called Magnetic Resonance Fingerprinting, which uses more sensitive scanning techniques that they expect could detect whether treatments are working after just one dose of chemo. [36] The standard approach to building a quantum computer with majoranas as building blocks is to convert them into qubits. However, a promising application of quantum computing—quantum chemistry—would require these qubits to be converted again into so-called fermions. [35] Scientists have shown how an optical chip can simulate the motion of atoms within molecules at the quantum level, which could lead to better ways of creating chemicals for use as pharmaceuticals. [34] Chinese scientists Xianmin Jin and his colleagues from Shanghai Jiao Tong University have successfully fabricated the largest-scaled quantum chip and demonstrated the first two-dimensional quantum walks of single photons in real spatial space, which may provide a powerful platform to boost analog quantum computing for quantum supremacy. [33] To address this technology gap, a team of engineers from the National University of Singapore (NUS) has developed an innovative microchip, named BATLESS, that can continue to operate even when the battery runs out of energy. [32] Stanford researchers have developed a water-based battery that could provide a cheap way to store wind or solar energy generated when the sun is shining and wind is blowing so it can be fed back into the electric grid and be redistributed when demand is high. -

Carlo Matteucci and the Legacy of Luigi Galvani

Archives Italiennes de Biologie, 149 (Suppl.): 3-9, 2011. Carlo Matteucci and the legacy of Luigi Galvani M. BRESADOLA Department of Humanities and Neuroscience Center, University of Ferrara, and National Institute of Neuroscience, Italy A bstract Carlo Matteucci (1811-1868) is considered one of the founders of electrophysiology, thanks to his research on electric fish, nerve conduction, and muscular contraction. In this essay Matteucci’s early investigation into life pro- cesses is discussed in the context of the debates on Galvanism, a new scientific field inaugurated by the discovery of animal electricity made by Luigi Galvani in the 1790s. Matteucci rejected both a “physicalist” and a “vitalist” interpretation of the phenomena of Galvanism, adopting instead the same view which had guided Galvani in his research on animal electricity. In this regard, Matteucci can be considered the true scientific heir of Galvani. Key words Matteucci, Carlo • Galvani, Luigi • Galvanism • History of electrophysiology Introduction of Moruzzi’s article; instead, I shall focus on some minor works which Matteucci published in the early In an article published in 1964, which still remains 1830s, in the period that preceded his major discov- the most relevant study of Carlo Matteucci’s sci- eries. My aim is to reconstruct the context in which entific work, Giuseppe Moruzzi claimed that “the Matteucci’s electrophysiological research began, electrophysiological work to which [Matteucci] owes and to identify some interests and motives which imperishable fame begins in 1836” (Moruzzi, 1964; guided Matteucci in his scientific investigation. To English translation in Moruzzi, 1996, p. 70). It was this end I shall examine the content of two papers in that year, in fact, that Matteucci identified the ner- which Matteucci published in 1830 and which vous centres responsible for the electrical discharge concerned some phenomena that were included in of Torpedo. -

THE JOURNAL of the ACOUSTICAL SOCIETY of AMERICA 170Th Meeting: Acoustical Society of America 138, No

The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America Vol. 138, No. 3, Pt. 2 of 2, September 2015 www.acousticalsociety.org 170th Meeting Acoustical Society of America Hyatt Regency Jacksonville Riverfront Hotel Jacksonville, Florida 2–6 November 2015 Table of Contents on p. A5 Published by the Acoustical Society of America through AIP Publishing LLC www.pcb.com/acoustics Booth #5 Come See Us at the ASA Exhibit Prepolarized Free-field Microphone Model 378B02 IEC 61094-4 compliant test and measurement microphone for audible range applications PERFORMANCE NOT JUST A MICROPHONE Inside every microphone is 40 years of sensor design and UNBEATABLE PRICE manufacturing expertise. Exceeding all expectations, our price, 24/7 TECH SUPPORT support, warranty and delivery are unmatched. BEST WARRANTY FAST SHIPMENT Toll Free in USA 800-828-8840 E-mail [email protected] Website www.pcb.com www.pcb.com/ShopSensors THE JOURNAL OF THE ACOUSTICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA ISSN: 0001-4966 Periodicals Postage Paid at Postmaster: If undeliverable, send notice on Form 3579 to: CODEN: JASMAN Huntington Station, NY and ACOUSTICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA Additional Mailing Offices 1305 Walt Whitman Road, Suite 300, Melville, NY 11747-4300 SAVE TIME AT EVERY STAGE FROM MEASUREMENT THROUGH TO REPORT FOR GOOD MEASURE Taking accurate acoustic measurements is critical – but not everything. You also need to efficiently document and report on what you’re doing to finish a project. Introducing the new Measurement Partner, a suite of innovative solutions that supports customers through every step of the measurement process. Take remote measurements with its Wi-Fi-enabled sound level meters so sound fields aren’t disturbed. -

![Massimo Tinazzi[*]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6331/massimo-tinazzi-4616331.webp)

Massimo Tinazzi[*]

Massimo Tinazzi[*] PERPETUAL ELECTROMOTIVE OF GIUSEPPE ZAMBONI. MANUFACTURE, COMPARISONS AND DEVELOPS During a cold morning at the end of the winter of 1812 abbot Giuseppe Zamboni gave to Veronese typographer Dionigio Ramanzini a manuscripts titled "Della pila elettrica a secco. Dissertazione", then two years later the typography Mainardi published his second work, "Descrizione ed uso dell'elettromotore perpetuo". These dates mark the first appearance in scientific literary of a brilliant experimenter that perfected his electrical machines with much meticulousness for following thirty years. Between 1820 and 1822 the heirs Merlo published the fundamental treatise in two great volumes with the title "L'elettromotore perpetuo", in which Zamboni developed and deepened the method to build and for the theoretical and experimental functioning of the instruments that he realized since 1810. We can say that this date marks the birth of the Zamboni dry piles and later the set-up of the first electrostatic clock: practically an electrical machine that was the starting point for the history of the finalized applications of the electricity, at least in Italy. With these preliminary statements I expected to find in Verona many evidences or biographical and monumental references to remember one of the most stimulating and active minds in this city. Instead few years after his death Giuseppe Zamboni seems to disappear from the cultural panorama of Verona. Today there is only a memorial tablet on the front of a building where he lived and that now belongs to the bishop, a marble bust in the entrance-hall of the Agriculture Science and Letters Academy in Verona, that has its seat in Erbisti Building, piece of the sculptor Grazioso Spazzi, in addition to a pair of portraits, one of this in the Academy and the other in the Liceo Classico Scipione Maffei in Verona. -

Team Members Are Proposed As Key Personnel

Multi-Modal Approaches to Real-Time Video Analysis Team Members: All team members are proposed as Key Personnel. Garrett T. Kenyon* [email protected] 505-667-1900 Dylan Paiton** [email protected] 505-720-5074 Pete Schultz [email protected] Vicente Malave [email protected] 619-800-4113 *lead developer, **alternate lead developer Description of Capability to be Delivered We intend to provide users with a high-performance (MPI-based, multi-core, GPU-accelerated) software tool for using biologically-inspired, hierarchical neural networks to detect objects of interest in streaming video by combining texture/color, shape and motion/depth cues. The system will be capable of processing video data or still imagery. The software to be provided will build upon an existing high-performance, open-source, NSF-funded neural simulation toolbox called PetaVision. Last fall, several members of our team worked closely together in an analogous boiler room atmosphere while competing in the DARPA NeoVision2 shootout. The close environment and hard deadline allowed for scientific advances at a more accelerated rate and forced innovative ways to combine traditionally independent algorithms. In particular, we found that by combining previously independent efforts to model different aspects of cortical visual processing, including local color/texture patches, long-range shape processing and relative depth from motion, we obtained better detection and localization accuracy than was possible using any of the individual processing techniques alone. By integrating a variety of new approaches to the implementation of these separate visual processing modalities and combining these modalities into a single simulation environment, we expect to produce dramatic improvements in the state-of-the- art of object detection and localization in high-definition video. -

Nature‑Inspired Structural Materials for Flexible Electronic Devices

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Nature‑Inspired Structural Materials for Flexible Electronic Devices Liu, Yaqing; He, Ke; Chen, Geng; Leow, Wan Ru; Chen, Xiaodong 2017 Liu, Y., He, K., Chen, G., Leow, W. R., & Chen, X. (2017). Nature‑Inspired Structural Materials for Flexible Electronic Devices. Chemical Reviews, 117(20), 12893‑12941. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/87992 https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00291 © 2017 American Chemical Society (ACS). This is the author created version of a work that has been peer reviewed and accepted for publication by Chemical Reviews, American Chemical Society (ACS). It incorporates referee’s comments but changes resulting from the publishing process, such as copyediting, structural formatting, may not be reflected in this document. The published version is available at: [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00291]. Downloaded on 28 Sep 2021 08:16:43 SGT Nature-inspired Structural Materials for Flexible Electronic Devices Yaqing Liu, Ke He, Geng Chen, Wan Ru Leow, and Xiaodong Chen* Innovative Centre for Flexible Devices (iFLEX), School of Materials Science and Engineering, Nanyang Technological University, 50 Nanyang Avenue, 639798, Singapore. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Exciting advancements have been made in the field of flexible electronic devices in the last two decades and will certainly lead to a revolution in peoples’ lives in the future. However, due to the poor sustainability of the active materials in complex stress environments, new requirements have been adopted for the construction of flexible devices. Thus, hierarchical architectures in natural materials, which have developed various environment-adapted structures and materials through natural selection, can serve as guides to solve the limitations of materials and engineering techniques. -

Carbon Nanotube Microarchitectures for Mechanical Metamaterials By

Carbon Nanotube Microarchitectures for Mechanical Metamaterials by Sei Jin Park A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Mechanical Engineering) in The University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor A. John Hart, Co-Chair, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Professor Wei Lu, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Xiaogan Liang Professor Anthony M. Waas © Sei Jin Park 2014 DEDICATION to Joyful smile, Unwavering character, Life, youthfulness, Love, peace and happiness, I dedicate this thesis And myself. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I arrived in Ann Arbor in the fall of 2005 as a naïve college freshman. Nine years later, I bid goodbye as a Doctor of Mechanical Engineering. So much has happened in that duration, and I am truly thankful for all the experiences that have led to this academic milestone. I would like to express my respect and deepest gratitude to my advisor Professor John Hart. It has been a great honor and privilege working with him. Without his guidance, I would not have dreamed of achieving a doctoral degree. His enthusiasm, insight, and drive are truly exceptional and have inspired me to become a better researcher. One of John’s admirable qualities as an advisor is that he always made time for his students despite his busy schedule. His devotion to his students is a testament to his mentorship and passion for training future scientists. I extend my appreciation to my doctoral committee members Professor Wei Lu, Professor Anthony Waas, and Professor Xiaogan Liang for their time and continuous support. They have offered invaluable advice throughout my graduate career. -

General Bibliography on Alessandro Volta

Georgia Santangelo and Carla Garbarino General Bibliography on Alessandro Volta We offer here to historians of science a bibliography which is meant to be an introduction to Alessandro Volta’s primary and secondary sources. While no such effort can claim completeness, we have done our best to include the most relevant titles found in a number of libraries. The first step was to search for items in OPACS (On-Line Public Access Catalogues) or in CD-ROMs of European and North American National Libraries, and in the most important collective catalogues (e.g. the British Library, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the Library of Congress, the Italian SBN [Sistema Bibliotecario Nazionale] and the ACNP [Archivio Collettivo Nazionale dei Periodici], the Karlsruhe Virtual Catalogue); besides, for the wealth of primary and secondary sources on the history of science, the Burndy Library of the Dibner Institute-Boston and the Bakken Library. Some researches have been carried out in situ: in France at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, at the Library of the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, at the Médiathèque of the Cité des Sciences et de l’Industrie; in Germany, at the Deutsches Museum Library; in Italy at the Public Library of Como, at the Istituto Lombardo and at the Brera Library in Milan, and at the University Library of Pavia, which, (born in the second part of the eighteenth century with a scientific bent), owns a rich heritage of scientific volumes and journals of that age. Regarding the works of Volta and his contemporaries, we examined some bibliographies on Volta, written in 1813,1 in 1877,2 and in 1900.3 In addition, we examined bibliographical references contained in the National Edition of Volta’s works4 and in the Regesto (catalogue) of Volta’s manuscripts (written by Alessandro 1 Catalogo delle opere state pubblicate dal Volta sino a tutto l’anno 1813.