Appendix 2 GRANGE CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hub South East Scotland Territory Annual Report 2016-2017

Hub South East Scotland Territory Annual Report 2016-2017 ‰ Hub South East: Your Development Partner of Choice Our achievements : 2010 onwards HUB PROJECTS VALUE OF VALUE IN SOUTH EAST SCOTLAND PROPORTION of CONSTRUCTION WORK PACKAGES AWARDED to £563m SCOTTISH SMEs £ 349 197m OPEN and OPERATIONAL NEW JOBS % £185m IN CONSTRUCTION created 87 £181m IN DEVELOPMENT GRADUATE & TRAINING EDUCATIONAL SUPPORT New and existing Site, School School and FE 290APPRENTICESHIP and FE Visits Work Placements and trainee places + + 27,000 3,300 Professional Employment persons days 110 including GRADUATES Figures correct at end July 2017 ‰ 2 ‰ Foreword – Chairs 4 ‰ Territory Programme Director’s Report 7 ‰ Hub South East Chief Executive’s Report 10 ‰ Projects Completed 13 ‰ Contents Under Construction 23 ‰ In Development 33 ‰ Strategic Support Services 39 ‰ Performance 43 ‰ Added Value through Hub South East 50 ‰ Abstract of Accounts 53 ‰ ‰ 3 ‰ Foreword Welcome to the 2016/17 Annual Report for the South East Territory, The Territory’s Strategic vision is to work together to provide enhanced local services covering the reporting period August 2016 to July 2017. and achieve tangible benefits for partners and communities in the Lothians and Borders and we have been making real headway in delivering it. This is our seventh year in operation, and we have continued to work together to improve local services by delivering modern, high quality This year in the South East Territory, we handed over our biggest completed project, community infrastructure across the Territory. Phase 1 of the development of the Royal Edinburgh Hospital campus (P18) and broke ground on our highest value revenue funded project at the East Lothian With eight projects on site and more in development, we are sustaining a Community Hospital (P28) - the largest project to date in the Hub programme across good level of activity. -

The Scottish Genealogist

THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGY SOCIETY THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGIST INDEX TO VOLUMES LIX-LXI 2012-2014 Published by The Scottish Genealogy Society The Index covers the years 2012-2014 Volumes LIX-LXI Compiled by D.R. Torrance 2015 The Scottish Genealogy Society – ISSN 0330 337X Contents Please click on the subject to be visited. ADDITIONS TO THE LIBRARY APPRECIATIONS ARTICLE TITLES BOOKMARKS BOOK REVIEWS CONTRIBUTORS FAMILY TREES GENERAL INDEX ILLUSTRATIONS INTRODUCTION QUERIES INTRODUCTION Where a personal or place name is mentioned several times in an article, only the first mention is indexed. LIX, LX, LXI = Volume number i. ii. iii. iv = Part number 1- = page number ; - separates part numbers within the same volume : - separates volume numbers BOOKMARKS The contents of this CD have been bookmarked. Select the second icon down at the left-hand side of the document. Use the + to expand a section and the – to reduce the selection. If this icon is not visible go to View > Show/Hide > Navigation Panes > Bookmarks. Recent Additions to the Library (compiled by Joan Keen & Eileen Elder) LIX.i.43; ii.102; iii.154: LX.i.48; ii.97; iii.144; iv.188: LXI.i.33; ii.77; iii.114; Appreciations 2012-2014 Ainslie, Fred LIX.i.46 Ferguson, Joan Primrose Scott LX.iv.173 Hampton, Nettie LIX.ii.67 Willsher, Betty LIX.iv.205 Article Titles 2012-2014 A Call to Clan Shaw LIX.iii.145; iv.188 A Case of Adultery in Roslin Parish, Midlothian LXI.iv.127 A Knight in Newhaven: Sir Alexander Morrison (1799-1866) LXI.i.3 A New online Medical Database (Royal College of Physicians) -

Astley Ainslie Hospital 1

Astley Ainslie Hospital Community Consultation Disposal Commitment Introduction The Astley Ainslie Hospital has now been declared surplus to NHS Lothian clinical strategy requirements. Services are being relocated as part of the closure process, the majority most within the nearby Royal Edinburgh Hospital campus. As part of the process of disposing of surplus assets NHS Lothian is committing to engaging with all key stakeholders, including the general public, MSP's Councilors, CEC planning department, Historic Environment Scotland and other interest groups to collate ideas and issues that are of importance to the community. Purpose of document With service re-provision still at the planning stage there is a substantial period available for community engagement prior to any disposal route being implemented. Meetings have already been held with local Community Council representatives, MSP's and the general public. The purpose of this document is to confirm NHS Lothian’s commitment to on-going engagement and to suggest a plan for the nature of this engagement and the documentation that will demonstrate the prioritised outcomes which will inform a disposal. This information will be used to create the criteria which all parties will use to establish the re-use of the land and buildings. It will form the basis of a document creating the most important development parameters for the site. This document will be formalised by way of a Development Brief containing all main development aspects and will be offered to CEC planning department for endorsement Engagement commitment • Inclusion – NHS Lothian is seeking to engage with all stakeholders to provide the widest range of interests the opportunity to provide their opinions. -

Consultant Medical Oncologist (Breast/Renal) in Cancer Services

JOB TITLE: Consultant Medical Oncologist (Breast/Renal) in Cancer Services JOB REFERENCE: CG 2054 JOBTRAIN REFERENCE: 044290 CLOSING DATE: 03 April 2021 INTERVIEW DATE: 06 May 2021 http://careers.nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk Contents Section Section 1: Person Specification Section 2: Introduction to Appointment Section 3: Departmental and Directorate Information Section 4: Main Duties and Responsibilities Section 5: Job Plan Section 6: Contact Information Section 7: Working for NHS Lothian Section 8: Terms and Conditions of Employment Section 9: General Information for Candidates Unfortunately we cannot accept CV’s as a form of application and only application forms completed via the Jobtrain system will be accepted. Please visit https://apply.jobs.scot.nhs.uk for further details on how to apply. You will receive a response acknowledging receipt of your application. This post requires the post holder to have a PVG Scheme membership/record. If the successful applicant is not a current PVG member for the required regulatory group i.e. child and/or adult, then an application will need to be made to Disclosure Scotland and deemed satisfactory before the successful post holder can commence work. All NHS Scotland and NHS Lothian Medical vacancies are advertised on our medical jobs microsite: www.medicaljobs.scot.nhs.uk Please visit our Careers website for further information on what NHS Lothian has to offer http://careers.nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk http://careers.nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk Section 1: Person Specification REQUIREMENTS ESSENTIAL DESIRABLE -

Notice of Meeting and Agenda

Planning Committee 10am, Thursday 7 August 2014 Grange Conservation Area Character Appraisal – Final Version Item number Report number Executive/routine Executive Wards Meadows/Morningside, Southside/Newington Executive summary The Grange Conservation Area Character Appraisal is the first of a series to be revised to reflect changing circumstances, community concerns and to produce a more user- friendly document. The document has resulted from an intensive programme of engagement with local community organisations and consultation within the Council. Feedback on the draft appraisal has been generally very positive. Detailed comments, concerns and suggestions have been reflected in the final version. The final version of the document is presented here for approval. Links Coalition pledges P40 Council outcomes CO19, CO23 Single Outcome Agreement SO4 Report Grange Conservation Area Character Appraisal – Final Version Recommendations 1.1 It is recommended that the committee approves the attached final version of the Grange Conservation Area Character Appraisal. Background 2.1 On 27 February 2014, the Planning Committee approved the revised Grange Conservation Area Character Appraisal in draft for consultation. Main report 3.1 Consultation on the draft appraisal ran from 12 March to 14 April 2014. An exhibition in Newington Library ran from 17 to 30 March and received about 40 visitors over the two sessions which were staffed by planning officers. Direct consultations were sent to 43 local and national interest groups. 3.2 The consultation generated 36 responses in total, 33 via the online survey and 3 directly by email. The majority of responses (31) were from individuals, mostly residents in the area. The Grange Association, Grange and Prestonfield Community Council, NHS Lothian, Falcon Bowling and Tennis Club and Carlton Cricket Club sent detailed responses. -

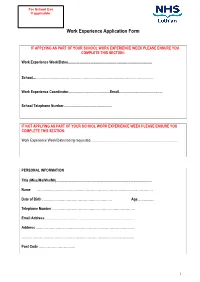

Work Experience Application Form

For School Use If applicable: Work Experience Application Form IF APPLYING AS PART OF YOUR SCHOOL WORK EXPERIENCE WEEK PLEASE ENSURE YOU COMPLETE THIS SECTION: Work Experience Week/Dates........................................................................................... School....……………………………………………………………………………………………. Work Experience Coordinator.............................................Email............................................... School Telephone Number.................................................... IF NOT APPLYING AS PART OF YOUR SCHOOL WORK EXPERIENCE WEEK PLEASE ENSURE YOU COMPLETE THIS SECTION: Work Experience Week/Dates being requested............................................................................................. PERSONAL INFORMATION Title (Miss/Ms/Mrs/Mr)....................................................................................................... Name …………………………………………………………………………………………… Date of Birth ……………………………………………………… Age.................. Telephone Number ………………………………………………………………… Email Address ……………………………………………………………………… Address ……………………………………………………………………………… ………………………………………………………………………………………… Post Code …………………………… 1 PLEASE INDICATE YOUR CHOSEN CAREER PATH …………………………………………………………………………………………. Please indicate your choice of placement and list your 1. preference in order (e.g. midwifery, cardiology) 2. 3. PLEASE INDICATE THE LOCATIONS YOU CAN CONSIDER Placement Location: using numbers (1 being your first choice, 2 being your second choice, etc) please mark all the areas that you could -

The Scottish Genealogist

THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGY SOCIETY THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGIST INDEX TO VOLUMES LIX-LXI 2012-2014 Published by The Scottish Genealogy Society The Index covers the years 2012-2014 Volumes LIX-LXI Compiled by D.R. Torrance 2015 The Scottish Genealogy Society – ISSN 0330 337X Contents Appreciations 1 Article Titles 1 Book Reviews 3 Contributors 4 Family Trees 5 General Index 9 Illustrations 6 Queries 5 Recent Additions to the Library 5 INTRODUCTION Where a personal or place name is mentioned several times in an article, only the first mention is indexed. LIX, LX, LXI = Volume number i. ii. iii. iv = Part number 1- = page number ; - separates part numbers within the same volume : - separates volume numbers Appreciations 2012-2014 Ainslie, Fred LIX.i.46 Ferguson, Joan Primrose Scott LX.iv.173 Hampton, Nettie LIX.ii.67 Willsher, Betty LIX.iv.205 Article Titles 2012-2014 A Call to Clan Shaw LIX.iii.145; iv.188 A Case of Adultery in Roslin Parish, Midlothian LXI.iv.127 A Knight in Newhaven: Sir Alexander Morrison (1799-1866) LXI.i.3 A New online Medical Database (Royal College of Physicians) LX.iv.177 A very short visit to Scotslot LIX.iii.144 Agnes de Graham, wife of John de Monfode, and Sir John Douglas LXI.iv.129 An Octogenarian Printer’s Recollections LX.iii.108 Ancestors at Bannockburn LXI.ii.39 Andrew Robertson of Gladsmuir LIX.iv.159: LX.i.31 Anglo-Scottish Family History Society LIX.i.36 Antiquarian is an odd name for a society LIX.i.27 Balfours of Balbirnie and Whittinghame LX.ii.84 Battle of Bannockburn Family History Project LXI.ii.47 Bothwells’ Coat-of-Arms at Glencorse Old Kirk LX.iv.156 Bridges of Bishopmill, Elgin LX.i.26 Cadder Pit Disaster LX.ii.69 Can you identify this wedding party? LIX.iii.148 Candlemakers of Edinburgh LIX.iii.139 Captain Ronald Cameron, a Dungallon in Morven & N. -

Ellen's Glen House – Hawthorn Ward

Ellen’s Glen House – Hawthorn Ward Hawthorn ward is a 30 bedded complex clinical care ward which specialises in palliative and end of life care. We have two respite beds which enable us to provide support for families caring for their loved one at home. Our patient group can vary from someone in the late 40s to someone in their 90s. Patients are complex and have multiple co-morbidities ranging from Cancer, Stroke, Parkinsons Disease, MS and Diabetes to name a few. Hawthorn ward is located on the first floor of Ellen’s Glen House, which is part of Edinburgh Health and Social Care Partnerships community hospitals and is situated on Edinburgh’s Southside just off the Lasswade Road. It easily accessed by Bus or car and has its own onsite parking. We aspire to provide excellent, individualised care and actively encourage patients and their relatives to be involved in any decisions regarding their care. We strive to provide high quality person centred care for our patients and the team works very hard to achieve these goals. Unfortunately our patients tend to be with us for short periods of time, due to the nature of their illness. This makes it even more important for us as a team to ensure we give them a sense of belonging and worth, and help make meaningful contributions to decisions on their care and wellbeing. Hawthorn ward has a friendly and welcoming team environment. It is a great place to start off your Nursing career and equally we welcome staff with experience. There are plenty opportunities to enhance your knowledge and undertake further training ie: Flying start, National Procedural Award, extended roles. -

PCJMG Minutes 12.12.13

Primary Care Contractor Organisation and Community Health (and Care) Partnerships PRIMARY CARE JOINT MANAGEMENT GROUP Note of meeting held at 1pm on Thursday 12 December 2013 in the Boardroom, St Roque, Astley Ainslie Hospital. Present: Dr Nigel Williams, Ass. Medical Director (depute Chair) Tim Montgomery, Edinburgh CHP Steve Faulkner, PCCO Dr Hamish Reid, Midlothian CHP Jane Houston, Partnership Dr Pete Shishodia, GP Sub-Committee Mark Hunter, PCCO Finance Dr Sian Tucker, LUCS Dr James McCallum, West Lothian CHCP Dr Jon Turvill, East Lothian CHP Stephen McBurney, Community Pharmacy Kevin Wallace, Area Ophthalmic Committee (deputising for Sandra McNaughton) David White, Edinburgh CHP Lizzie McGeechan, PCCO Alison McNeillage, PCCO In attendance: Lee Doyle (notes) Apologies: Marion Christie, Lynda Cowie, Dr Ian McKay, Sandra McNaughton, Robert Packham, David Small. Introduction and Welcome 72. Minute of Meeting on 14 November 2013 72.1 The draft minute of the meeting on the 14 November 2013 was approved as an accurate record. 72.2 Review of progress on specific ongoing actions: 416 National Community Pharmacy Contract – deferred until January. 72 Flu Immunisation of House Bound Patients – 20 practices have taken up the LES with 528 hard to reach patients being identified to the Community Vaccination Team. 127 Care Homes – ‘Complex Frail Elderly in the Community’ draft paper will be taken to the Enhanced Services Review Group meeting on 17/12/13 (Dr Nigel Williams). 64 Edinburgh CHP proposal for standardising/agreeing funding for practices offering services to care homes to the PCJMG for comment – on agenda. Completed 35 Extended Immunisation Programme – Child Immunisation programme going well. -

Lothian NHS Board Waverley Gate 2-4 Waterloo Place Edinburgh EH1 3EG

Lothian NHS Board Waverley Gate 2-4 Waterloo Place Edinburgh EH1 3EG Telephone: 0131 536 9000 www.nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk www.nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk Date: 26/11/2020 Your Ref: Our Ref: 4769 Enquiries to : Richard Mutch Extension: 35687 Direct Line: 0131 465 5687 [email protected] [email protected] Dear FREEDOM OF INFORMATION – BACKLOG MAINTENANCE I write in response to your request for information in relation to backlog maintenance within NHS Lothian. Question: The size in terms of estimated cost of the current repairs backlog at each hospital within the health board. Answer: Site Name Total BELHAVEN HOSPITAL 27,091.16 BELHAVEN HOSPITAL 237,995.14 BELHAVEN HOSPITAL 143,782.98 EDINGTON COTTAGE HOSPITAL 2,578.84 WESTERN GENERAL HOSPITAL 20,487,272.68 WESTERN GENERAL HOSPITAL 1,627,052.49 WESTERN GENERAL HOSPITAL 2,235,126.53 ASTLEY AINSLIE HOSPITAL 2,821,673.59 ASTLEY AINSLIE HOSPITAL 2,818,364.43 ASTLEY AINSLIE HOSPITAL 1,267,424.57 LIBERTON HOSPITAL 1,429,263.08 LIBERTON HOSPITAL 209,569.02 LIBERTON HOSPITAL 441,477.45 ROYAL EDINBURGH HOSPITAL 1,944,980.83 ROYAL EDINBURGH HOSPITAL 266,362.80 ROYAL EDINBURGH HOSPITAL 825,518.13 ROYAL HOSPITAL FOR SICK CHILDREN 863,468.66 Backlog Maintenance - November 2020 ROYAL HOSPITAL FOR SICK CHILDREN 662,327.15 ROYAL HOSPITAL FOR SICK CHILDREN 18,677.34 ST. MICHAELS HOSPITAL 9,408.02 ST. MICHAELS HOSPITAL 24,125.87 ST. MICHAELS HOSPITAL 1,164,395.38 ST. JOHNS HOSPITAL 6,879,018.43 ST. JOHNS HOSPITAL 614,916.61 PRINCESS ALEXANDRA EYE PAVILION 4,941,345.92 Question: The proportion of this backlog that is considered to be a) high risk and b) significant risk Answer: Significant High Total 26,522,347.73 401,249.43 51,963,217.10 I hope the information provided helps with your request. -

International Forum on Quality & Safety in Healthcare Experience

International Forum on Quality & Safety in Healthcare Experience Visit to NHS Lothian – 27 March 2019 Experience Day 5: Innovative approaches to anticipatory patient care and mental health 09.00am: ● Group 1 (50 delegates) departure by coach for Astley Ainslie Hospital 09.30am ● Group 2 (25 delegates) departure by coach for Newbattle High School Group 1 programme 10.30am: Arrival at Astley Ainslie Hospital. Refreshments, Welcome & Introduction – Simon Watson, Chief Quality Officer, NHS Lothian 11.00am: Departure for experience sessions. 25 delegates per group. Astley Ainslie Hospital (on site) Royal Edinburgh Hospital (approx. 10 mins transport) Session 1: Flow Centre, Astley Ainslie Hospital The Flow Centre supports the flow of patients across all adult acute sites in Lothian, managing all referrals for urgent acute care, either in the community or in a hospital setting. The Flow Centre manages and co-ordinates all transport for transfers and discharges across Lothian, including repatriations to other Boards out with Lothian. Delegates will be able hear from sites, staff in the community and see the Flow Centre in action, hear about how it was created with opportunity to view transport options. This award winning team has implemented a robust safety and clinical governance framework to ensure the safety of patients at the interface between primary and secondary care. From initial contact to the patient being admitted or arriving home, the Flow Centre ensures that the patient is seen in the right place at the right time by -

Introduction

Lothian Enteral Tube Feeding Best Practice Statement Introduction This document has been produced by the Lothian Enteral Tube Feeding Best Practice Statement Review Group. The group was established in May 2012 and devised a workplan. The remit of the Review Group was to update the Lothian Enteral Tube Feeding Best Practice Statement for Adults and Children that was published in December 2007. The content of the original document was reviewed, updated as necessary and new sections added to incorporate evidence since 2007. Where possible the recommendations are based on evidence, research or National Guidance. Where this was not available some statements are based on consensus of expert opinion and any related reference(s) listed. The Best Practice Statement applies to all adult, paediatric and neonate patients in Lothian, with the exception of the neonates in Simpson’s Reproductive Centre, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh and St John’s Hospital. It is intended that this best practice statement should be implemented across NHS Lothian for hospitals and community. The Best Practice Statement will be reviewed on a rolling programme as required. At time of publication, some sections are currently under review, and this is clearly stated within the document. Julia Mackel Chair - Lothian Enteral Tube Feeding Best Practice Statement Review Group Review group membership Ruth Hymers Senior Dietitian Western General Hospital, Edinburgh Jenny Livingstone Senior Paediatric Dietician Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh Julia Mackel (Chair) CENT