The Migration from Singsås, Orway, to the Upper Midwest, 1850-1905

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horg, Hov and Ve – a Pre-Christian Cult Place at Ranheim in Trønde- Lag, Norway, in the 4Rd – 10Th Centuries AD

Preben Rønne Horg, hov and ve – a pre-Christian cult place at Ranheim in Trønde- lag, Norway, in the 4rd – 10th centuries AD Abstract In the summer of 2010 a well-preserved cult place was excavated at Ranheim on Trondheim Fjord, in the county of Sør-Trøndelag, Norway. The site consisted of a horg in the form of a flat, roughly circular stone cairn c.15 m in diameter and just under 1 m high, a hov in the form of an almost rectangular building with strong foundations, and a processional avenue marked by two stone rows. The horg is presumed to be later than c. AD 400. The dating of the hov is AD 895–990 or later, during a period when several Norwegian kings reigned, including Harald Hårfager (AD 872–933), and when large numbers of Norwegians emigrated and colonized Iceland and other North Atlantic islands between AD 874 and AD 930 in response to his ruth- less regime. The posts belonging to the hov at Ranheim had been pulled out and all of the wood removed, and the horg had been carefully covered with stones and clay. Thereafter, the cult place had been entirely covered with earth, presumably during the time of transition to Christianity, and was thus effectively concealed and forgotten until it was excavated in 2010. Introduction Since the mid-1960s until about 2000 there has have been briefly mentioned by Lars Larsson been relatively little research in Scandinavia fo- in Antiquity in connection with his report on cusing on concrete evidence for Norse religion a ritual building at Uppåkra in Skåne (Larsson from religious sites, with the exception of Olaf 2007: 11–25). -

Trondheim Cruise Port Events: Trondheim Jazz Festival (June) , St

TrONDHeiM CruiSe POrT Events: Trondheim Jazz Festival (June) www.jazzfest.no , St. Olavs Festival (July/August) www.olavsfestdagene.no, Trondheim Food Festival (August) www.tronderskmatfestival.no. Cruise season: May – September. Tourist Information: www.visit-trondheim.com | www.visitnorway.com | Page 52 | Page | www.visitnorway.com Trondheim Photo: Johan Berge/Innovation Norway Nidaros Cathedral Photo: Terje Rakke, Nordic Life Guided tour of the city Guided city walk World Heritage Site Røros Daily at 12.00 from 30.05 – 28.08. Daily at 14.00 from 27.06 – 21.08. Distance from Trondheim Harbour: 160 km Languages: Norwegian, english and German Languages; Norwegian and english. The town of Røros is one of the oldest towns of Duration: 2 hours, start from the market square. Duration: 1.5 - 2 hours wooden buildings in Europe, and also one of the few Capacity; 50 persons. Start from Tourist information Office. mining towns in the world that has been found worthy Tickets are sold at the Tourist information Office. Tickets are sold at the Tourist information Office. a place at UNESCO’S World Heritage List. A tour of Trondheim and its outskirts. We visit Join us for a walk through the streets of Trondheim, The town centre boasts a rare collection of large and Haltdalen Stave Church at the Folk Museum, and sense the city’s history that stretches from the well preserved wooden buildings, made all the more pass the Norwegian University of Science and Middle Ages to our own high-tech society! real and authentic by the fact that the people of today Technology, Kristiansten Fort, the Royal Residence live and work in them. -

Høring Av Søknad Om Driftskonsesjon for Utvidelse Av Solberg Steinbrudd I Midtre Gauldal Kommune

Adresseinformasjon fylles inn ved ekspedering. Dato: 27.05.2019 Se mottakerliste nedenfor. Vår ref: 17/02640-12 Deres ref: Høring av søknad om driftskonsesjon for utvidelse av Solberg steinbrudd i Midtre Gauldal kommune. Tiltakshaver: Koren Sprengningsservice AS. Leiv Erikssons vei 39 Direktoratet for mineralforvaltning med Bergmesteren for Svalbard (DMF) har mottatt Postboks 3021 Lade N-7441 Trondheim søknad om driftskonsesjon etter mineralloven § 43, datert 28. juni 2017. TELEFON + 47 73 90 46 00 Søknaden om driftskonsesjon sendes med dette på høring til aktuelle høringsinstanser [email protected] E-POST for at saken skal bli tilstrekkelig belyst, i henhold til forvaltningsloven § 17. Vi ber WEB www.dirmin.no kommunen om å informere oss så snart som mulig hvis det er særlig berørte parter GIRO 7694.05.05883 som ikke står på adresselista for denne høringen. SWIFT DNBANOKK IBAN NO5376940505883 ORG.NR. NO 974 760 282 Høringsfrist: 24. juni 2019. SVALBARDKONTOR Søknaden med vedlegg er tilgjengelig på dirmin.no under ”Saker til høring”. TELEFON +47 79 02 12 92 Sammendrag av søknaden Koren Sprengningsservice AS søker om driftskonsesjon for utvidelse av Solberg steinbrudd. Uttaket er lokalisert på gbnr. 130/1 i Midtre Gauldal kommune. Tiltakshaver oppgir at omsøkt areal er ca. 185 daa. Tiltakshaver har allerede fått tildelt driftskonsesjon for uttak av masser innenfor et område på 62 daa. Dette konsesjonsområdet samsvarer med det som tidligere var avsatt til råstoffutvinning i kommuneplanens arealdel. I etterkant av dette har tiltakshaver fått regulert et større område til råstoffutvinning. DMF har lagt til grunn at omsøkt område er det som i gjeldende reguleringsplan er regulert til råstoffutvinning, med unntak av området hvor det allerede er gitt konsesjon. -

NORWAY Welcome to Hurtigruten

2010 The Norwegian Coastal Voyage NORWAY Welcome to Hurtigruten Hurtigruten is renowned for its comprehensive and adventurous voyages. With 117 years of maritime experience and a fleet of thirteen comfortable ships, we offer voyages that go beyond the realms of other liners, providing the best in specialist knowledge and expertise on journeys that exceed expectations and provide an opportunity to encounter environments, wildlife, and people. NORWAY Our ships have been an integral part of Norwegian coastal life for generations, with daily departures from Bergen crossing the Arctic Circle to sail deeper into the heart of this spectacular landscape. Beneath the dazzling brilliance of the Midnight Sun or the Northern Lights, these regular sailings call at remote ports almost never visited by com- mercial liners, bringing passengers to isolated communities lying amid a backdrop of breathtaking scenery. 71° N NOR WA Y NORTH CAPE Mehamn Berlevag Honningsvag Batsfjord Havoysund Hammerfest Kjollefjord Vardo CONTENTS Oksfjord Vadso 4–5 The Voyage You’ve Always Dreamed of Kirkenes THEME VOYAGES Tromso Skjervoy RUSSIA 6–7 Connecting Coastal Communities VESTERALEN 44–45 Give Your Journey an Extra Dimension Risoyhamn 8–9 Hurtigruten and National Geographic Finnsnes 46–49 Hurtigruten’s Theme Voyages Sortland 10–11 Discover the Norwegian Fjords Stokmarknes Harstad FINLAND Svolvaer 12–13 Spring—Three Seasons In Five Days PRE- & POST-CRUISE EXCURSIONS Stamsund 14–15 Summer—24-Hour Natural Reading Light & EXPLORATIONS 16–17 Autumn—Experience Stunning Bright -

Administrative and Statistical Areas English Version – SOSI Standard 4.0

Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 Administrative and statistical areas Norwegian Mapping Authority [email protected] Norwegian Mapping Authority June 2009 Page 1 of 191 Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 1 Applications schema ......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Administrative units subclassification ....................................................................................7 1.1 Description ...................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 CityDistrict ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 CityDistrictBoundary ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.3 SubArea ................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 BasicDistrictUnit ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.5 SchoolDistrict ........................................................................................................... 16 1.1.6 <<DataType>> SchoolDistrictId ............................................................................... 17 1.1.7 SchoolDistrictBoundary ........................................................................................... -

Kommunedelplan for Kulturminner (Kulturminneplan)

Kommunedelplan for kulturminner (kulturminneplan) Holtålen kommune 2021 – 2026 Eidet smeltehytte Kommunedelplan for kulturminner – Holtålen kommune – forslag 15.03.2021 2 1. Innholdsfortegnelse: 2. Bakgrunn: ..................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Innledning: ................................................................................................................................... 4 4. Forholdet til retningslinjer og andre planer: ....................................................................... 5 5. Hva er et kulturminne? .............................................................................................................. 6 6. Hvorfor skal vi ta vare på kulturminner? .............................................................................. 6 7. Begrepsavklaring: ...................................................................................................................... 7 8. Om arbeidet og utvelgelse: ...................................................................................................... 8 9. Museene og kulturminnefeltet: ............................................................................................... 8 9.1 Ålen bygdemuseum: ............................................................................................................... 9 9.2 Petran museum: ...................................................................................................................... -

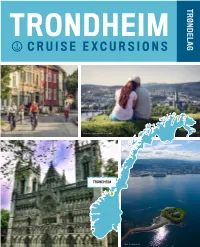

Cruise Excursions

TRØNDELAG TRONDHEIM CRUISE EXCURSIONS Photo: Steen Søderholm / trondelag.com Photo: Steen Søderholm / trondelag.com TRONDHEIM Photo: Marnie VIkan Firing Photo: Trondheim Havn TRONDHEIM TRØNDELAG THE ROYAL CAPITAL OF NORWAY THE HEART OF NORWEGIAN HISTORY Trondheim was founded by Viking King Olav Tryggvason in AD 997. A journey in Trøndelag, also known as Central-Norway, will give It was the nation’s first capital, and continues to be the historical you plenty of unforgettable stories to tell when you get back home. capital of Norway. The city is surrounded by lovely forested hills, Trøndelag is like Norway in miniature. Within few hours from Trond- and the Nidelven River winds through the city. The charming old heim, the historical capital of Norway, you can reach the coastline streets at Bakklandet bring you back to architectural traditions and with beautiful archipelagos and its coastal culture, the historical the atmosphere of days gone by. It has been, and still is, a popular cultural landscape around the Trondheim Fjord and the mountains pilgrimage site, due to the famous Nidaros Cathedral. Trondheim in the national parks where the snow never melts. Observe exotic is the 3rd largest city in Norway – vivid and lively, with everything animals like musk ox or moose in their natural environment, join a a big city can offer, but still with the friendliness of small towns. fishing trip in one of the best angler regions in the world or follow While medieval times still have their mark on the center, innovation the tracks of the Vikings. If you want to combine impressive nature and modernity shape it. -

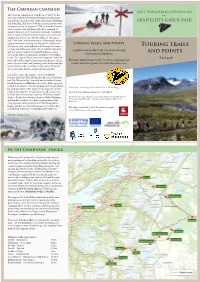

Touring Trails and Points Norway on Poor Roads and Paths

The Carolean campaign The Carolean campaign on Trondheim, 1718–1719, has seriously affected the Swedish-Norwegian border region and still lives on in the souls of the inhabitants of Jämtland and Trøndelag. The days of Sweden as a great power were coming to an end. In August of 1718 an army of Carolean soldiers gathered in Jämtland under the command of General Armfeldt with the mission to invade Trondheim and the region of Trøndelag within a period of six weeks. Mobilised in Duved were 10 073 soldiers, 6 721 horses and 2 500 cattle. A troublesome war project began: heavy equipment was to be transported across the border into Touring trails and points Norway on poor roads and paths. In Norway the sconces Touring trails of Stene and Skåne were taken and via Stjørdal the heavy A guide in the tracks of the Caroleans through and wet march continued towards Trondheim. Along and points the way the army was repeatedly attacked by Norwegian Jämtland and Trøndelag troops. The siege of Trondheim took a long time and both Travel guide sides suffered from lack of provisions and diseases. All the For more information on the Carolean campaign and years of poor harvests and suffering prior to the campaign related activities, please visit www.karoliner.com only served to make the situation even worse. However, the actual battles had not resulted in many deaths. Late in December, the army received news that the Swedish King Karl XII had been shot dead at Fredrikstens fort. On Christmas Eve, Armfeldt and his withered army found themselves in Haltdalen where they held vespers at a small stave church. -

På Tur I Midtre Gauldal – Nasjonalparkkommune

MG:NYTT NO 02 JULI 2010 | INFORMASJONSAVIS FOR MIDTRE GAULDAL KOMMUNE PÅ TUR I MIDTRE GAULDAL – NASJONALPARKKOMMUNE Pilegrimsleia – en opplevelse 02 | NO 02 JULI 2010 Rådmann Knut Dukane Velkommen til kommunen vår! Dette nummeret av MG:nytt er spesielt viet kort- og langveisfarende besøkende. Turbok for Intensjonen er, foruten å gi informasjon om de mange ulike Midtre Gauldal severdighetene vi har, å pirre oppdagertrangen slik at den enkelte kan få muligheten til minneverdige opplevelser Midtre Gauldal er en vidstrakt kommune, og byr på opp- utenom allfarvei. levelser i en variert natur rik på kulturminner. Skal du ut i terrenget, er Turbok for Midtre Gauldal den perfekte guide Gjestfriheten er stor, og ikke minst besitter mange av langs vei, sti og lokalhistorie. tilbudsgiverne og andre fastboende et vell av historiske fakta og lokalkunnskap om mange fasetter ved folk, om Turbok for Midtre Gauldal tegner opp og foreslår turer i kultur, og plasser i vår vidstrakte og vakre kommune. Be- skog og mark, til fots, på sykkel og på ski rundt om kom- nytter en seg av dette, vil opplevelsene bli enda sterkere munen. Hver tur er vurdert ut fra hvor krevende de er, og og lettere å hente fram fra sinnets minebok i mørke høst gir anbefaling om passende form og alder. Sånn sett blir og vinterkvelder. boka en ypperlig ressurs for alle friluftslivsinteresserte, enten det er barnefamilier, aktive idrettsutøvere eller den Muligheter for variert fiske, studiet av mangeartet flora, gjengse turgåer som gjerne vil trø ut av sine vante stier for smak av tradisjonsmat og seterkost, og besøk på ulike å se mer av Midtre Gauldal. -

Samfunnsmessig Konsekvensanalyse Midtre Gauldal, 2020

Samfunnsmessig konsekvensanalyse Midtre Gauldal Konsekvenser av flyttingen av Norsk Kylling Bilde 1: Støren sentrum, Midtre Gauldal Trøndelag fylkeskommune 5.11.2020 Innhold Illustrasjonsliste ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Kart ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Tabeller ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Figurer ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Bilder ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Sammendrag av hovedfunn ................................................................................................................... 6 1. Bakgrunn ......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Kort om Kommunen ................................................................................................................ 8 1.2 Norsk Kylling .......................................................................................................................... 10 2. Befolkning .................................................................................................................................... -

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Department of Geology and Mineral Resources Engineering Management Front page: Kristian Drivenes in the field (Photo: Øystein Gjermshusengen) Mai Britt Mørk Rolf Arne Kleiv Bjørn Nilsen Head of Department, Mineral Production Ingenieering Geology Geology Group and HSE Group and Rock Mecanics Group Visiting address Department of Geology and Mineral Resources Engineering Sem Sælands vei 1 7491 Trondheim, Norway +47 73 59 48 00 [email protected] Marzena Ewa Grindal Torkjell Breivik www.ntnu.edu/igb Head of Office Head of Laboratory Scientific staff Professors Bjørge Brattli, Rolf Arne Kleiv, Hanumantha Rao Kota, Allan George Krill, Rune Berg-Edland Larsen, Charlie Chunlin Li, Stephen John Lippard, Suzanne McEnroe, Mai Britt E. Mørk, Bjørn Nilsen Associate Professors Terje Harald Bargel, Kristian Drivenes, Steinar Løve Ellefmo, Maarten Felix, Erik Stabell Ludvigsen, Krishna Kanta Panthi, Randi Kalskin Ramstad, Bjørn Eske Sørensen, Maria Thornhill, Kurt Aasly Adjunct Faculty Christine Fichler, Solveig Føreland, Eivind Grøv, Sunniva Haugen, Reginald Hermanns, Atle Mørk, Arve Næss, Quoc Nghia Trinh, Børge Johannes Wigum Temporary scientific staff Postdoctoral fellows and researchers Nathan Church, Harald Gether, Thomas Grant, Helge Rushfeldt Doctoral candidates Chhatra Bahadur Basnet, Liyuan Chi, Øyvind Dammyr, Priyanka Dhar, Justin Olabode Fadipe, Marit Fladvad, Sondre Gjengedal, Anette Utgården Granseth, Are Håvard Høien, Cyril Jerome Juliani, Hanne Kvitsand, Aleksandra Lang, Alexander Michels, Benedicte Eikeland Nilssen, -

NGU Rapport 91.117 Grunnvatn I Midtre Gauldal Kommune

NGU Rapport 91.117 Grunnvatn i Midtre Gauldal kommune Norges geologiske undersøkelse 7491 TRONDHEIM Tlf. 73 90 40 00 Telefaks 73 92 16 20 RAPPORT Rapport nr.: 91.117 ISSN 0800-3416 Gradering: Åpen Tittel: Grunnvatn i Midtre Gauldal kommune Forfatter: Oppdragsgiver: Soldal O., Grønlie A. Miljøverndepartementet, NGU Fylke: Kommune: Sør-Trøndelag Midtre Gauldal Kartblad (M=1:250.000) Kartbladnr. og -navn (M=1:50.000) Trondheim, Røros 1520 I, 1620 IV Forekomstens navn og koordinater: Sidetall: 12 Pris: 50,- Kartbilag: Feltarbeid utført: Rapportdato: Prosjektnr.: Ansvarlig: Juni 1990 05.03.91 63.2521.32 Sammendrag: Midtre Gauldal kommune er ein A-kommune i GiN-prosjektet. Vurderigane byggjer på tidlegare undersøkningar samt synfaring i dei ulike områda. For dei prioriterte stadane er konklusjonen: Soknedal – mogeleg i lausmassar, Forsetmo – mogeleg i lausmassar, Enodd – mogeleg i lausmassar, Singsås – mogeleg i lausmassar, Støren – mogeleg i lausmassar. I Soknedal pågår det undersøkningar, for tida ser det ut til å vera mogeleg å løysa vassforsyninga ved hjelp av kunstig infiltrasjon. BEMERK at kommunene er skilt i A- og B-kommuner. Dette er gjort av fylkeskommunen etter oppfordring fra Miljøverndepartementet for å konsentrere innsatsen om de kommuner som har størst behov i henhold til GIN’s målsetting. I A-kommunene gjøres det feltarbeid, mens det ikke gjøres feltarbeid i B-kommunene. Der baseres vurderingene på eksisterende materiale og kunnskaper om forholdene uten at ny viten innhentes. Rapportens innhold vil derfor i regelen bære preg