The Function of the Antennae in Rhodnius Prolixus (Hemiptera) and the Mechanism of Orientation to the Host by V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trypanosoma Cruzi Immune Response Modulation Decreases Microbiota in Rhodnius Prolixus Gut and Is Crucial for Parasite Survival and Development

Trypanosoma cruzi Immune Response Modulation Decreases Microbiota in Rhodnius prolixus Gut and Is Crucial for Parasite Survival and Development Daniele P. Castro1*, Caroline S. Moraes1, Marcelo S. Gonzalez2, Norman A. Ratcliffe1, Patrı´cia Azambuja1,3, Eloi S. Garcia1,3 1 Laborato´rio de Bioquı´mica e Fisiologia de Insetos, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Fundac¸a˜o Oswaldo Cruz (Fiocruz), Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2 Laborato´rio de Biologia de Insetos, Departamento de Biologia Geral, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF) Nitero´i, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3 Departamento de Entomologia Molecular, Instituto Nacional de Entomologia Molecular (INCT-EM), Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Abstract Trypanosoma cruzi in order to complete its development in the digestive tract of Rhodnius prolixus needs to overcome the immune reactions and microbiota trypanolytic activity of the gut. We demonstrate that in R. prolixus following infection with epimastigotes of Trypanosoma cruzi clone Dm28c and, in comparison with uninfected control insects, the midgut contained (i) fewer bacteria, (ii) higher parasite numbers, and (iii) reduced nitrite and nitrate production and increased phenoloxidase and antibacterial activities. In addition, in insects pre-treated with antibiotic and then infected with Dm28c, there were also reduced bacteria numbers and a higher parasite load compared with insects solely infected with parasites. Furthermore, and in contrast to insects infected with Dm28c, infection with T. cruzi Y strain resulted in a slight decreased numbers of gut bacteria but not sufficient to mediate a successful parasite infection. We conclude that infection of R. prolixus with the T. cruzi Dm28c clone modifies the host gut immune responses to decrease the microbiota population and these changes are crucial for the parasite development in the insect gut. -

When Hiking Through Latin America, Be Alert to Chagas' Disease

When Hiking Through Latin America, Be Alert to Chagas’ Disease Geographical distribution of main vectors, including risk areas in the southern United States of America INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION 2012 EDITION FOR MEDICAL ASSISTANCE For updates go to www.iamat.org TO TRAVELLERS IAMAT [email protected] www.iamat.org @IAMAT_Travel IAMATHealth When Hiking Through Latin America, Be Alert To Chagas’ Disease COURTESY ENDS IN DEATH segment upwards, releases a stylet with fine teeth from the proboscis and Valle de los Naranjos, Venezuela. It is late afternoon, the sun is sinking perforates the skin. A second stylet, smooth and hollow, taps a blood behind the mountains, bringing the first shadows of evening. Down in the vessel. This feeding process lasts at least twenty minutes during which the valley a campesino is still tilling the soil, and the stillness of the vinchuca ingests many times its own weight in blood. approaching night is broken only by a light plane, a crop duster, which During the feeding, defecation occurs contaminating the bite wound periodically flies overhead and disappears further down the valley. with feces which contain parasites that the vinchuca ingested during a Bertoldo, the pilot, is on his final dusting run of the day when suddenly previous bite on an infected human or animal. The irritation of the bite the engine dies. The world flashes before his eyes as he fights to clear the causes the sleeping victim to rub the site with his or her fingers, thus last row of palms. The old duster rears up, just clipping the last trees as it facilitating the introduction of the organisms into the bloodstream. -

A New Species of Rhodnius from Brazil (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 675: 1–25A new (2017) species of Rhodnius from Brazil (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae) 1 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.675.12024 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research A new species of Rhodnius from Brazil (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae) João Aristeu da Rosa1, Hernany Henrique Garcia Justino2, Juliana Damieli Nascimento3, Vagner José Mendonça4, Claudia Solano Rocha1, Danila Blanco de Carvalho1, Rossana Falcone1, Maria Tercília Vilela de Azeredo-Oliveira5, Kaio Cesar Chaboli Alevi5, Jader de Oliveira1 1 Faculdade de Ciências Farmacêuticas, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” (UNESP), Araraquara, SP, Brasil 2 Departamento de Vigilância em Saúde, Prefeitura Municipal de Paulínia, SP, Brasil 3 Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP), Campinas, SP, Brasil 4 Departa- mento de Parasitologia e Imunologia, Universidade Federal do Piauí (UFPI), Teresina, PI, Brasil 5 Instituto de Biociências, Letras e Ciências Exatas, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” (UNESP), São José do Rio Preto, SP, Brasil Corresponding author: João Aristeu da Rosa ([email protected]) Academic editor: G. Zhang | Received 31 January 2017 | Accepted 30 March 2017 | Published 18 May 2017 http://zoobank.org/73FB6D53-47AC-4FF7-A345-3C19BFF86868 Citation: Rosa JA, Justino HHG, Nascimento JD, Mendonça VJ, Rocha CS, Carvalho DB, Falcone R, Azeredo- Oliveira MTV, Alevi KCC, Oliveira J (2017) A new species of Rhodnius from Brazil (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae). ZooKeys 675: 1–25. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.675.12024 Abstract A colony was formed from eggs of a Rhodnius sp. female collected in Taquarussu, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, and its specimens were used to describe R. -

Vectors of Chagas Disease, and Implications for Human Health1

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Denisia Jahr/Year: 2006 Band/Volume: 0019 Autor(en)/Author(s): Jurberg Jose, Galvao Cleber Artikel/Article: Biology, ecology, and systematics of Triatominae (Heteroptera, Reduviidae), vectors of Chagas disease, and implications for human health 1095-1116 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Biology, ecology, and systematics of Triatominae (Heteroptera, Reduviidae), vectors of Chagas disease, and implications for human health1 J. JURBERG & C. GALVÃO Abstract: The members of the subfamily Triatominae (Heteroptera, Reduviidae) are vectors of Try- panosoma cruzi (CHAGAS 1909), the causative agent of Chagas disease or American trypanosomiasis. As important vectors, triatomine bugs have attracted ongoing attention, and, thus, various aspects of their systematics, biology, ecology, biogeography, and evolution have been studied for decades. In the present paper the authors summarize the current knowledge on the biology, ecology, and systematics of these vectors and discuss the implications for human health. Key words: Chagas disease, Hemiptera, Triatominae, Trypanosoma cruzi, vectors. Historical background (DARWIN 1871; LENT & WYGODZINSKY 1979). The first triatomine bug species was de- scribed scientifically by Carl DE GEER American trypanosomiasis or Chagas (1773), (Fig. 1), but according to LENT & disease was discovered in 1909 under curi- WYGODZINSKY (1979), the first report on as- ous circumstances. In 1907, the Brazilian pects and habits dated back to 1590, by physician Carlos Ribeiro Justiniano das Reginaldo de Lizárraga. While travelling to Chagas (1879-1934) was sent by Oswaldo inspect convents in Peru and Chile, this Cruz to Lassance, a small village in the state priest noticed the presence of large of Minas Gerais, Brazil, to conduct an anti- hematophagous insects that attacked at malaria campaign in the region where a rail- night. -

Redalyc.Towards an Understanding of the Interactions of Trypanosoma

Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências ISSN: 0001-3765 [email protected] Academia Brasileira de Ciências Brasil Azambuja, Patrícia; A. Ratcliffe, Norman; S. Garcia, Eloi Towards an understanding of the interactions of Trypanosoma cruzi and Trypanosoma rangeli within the reduviid insect host Rhodnius prolixus Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, vol. 77, núm. 3, set., 2005, pp. 397-404 Academia Brasileira de Ciências Rio de Janeiro, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=32777304 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências (2005) 77(3): 397-404 (Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences) ISSN 0001-3765 www.scielo.br/aabc Towards an understanding of the interactions of Trypanosoma cruzi and Trypanosoma rangeli within the reduviid insect host Rhodnius prolixus PATRÍCIA AZAMBUJA1, NORMAN A. RATCLIFFE2 and ELOI S. GARCIA1 1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz Av. Brasil 4365, 21045-900 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil 2Biomedical and Physiologial Research Group, School of Biological Sciences, University of Wales Swansea, Singleton Park, Swansea, SA28PP, United Kingdom Manuscript received on March 3, 2005; accepted for publication on March 30, 2005; contributed by Eloi S. Garcia* ABSTRACT This review outlines aspects on the developmental stages of Trypanosoma cruzi and Trypanosoma rangeli in the invertebrate host, Rhodnius prolixus. Special attention is given to the interactions of these parasites with gut and hemolymph molecules and the effects of the organization of midgut epithelial cells on the parasite development. -

The Occurrence of Rhodnius Prolixus Stal, 1859, Naturally Infected By

Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Vol. 93(2): 141-143, Mar./Apr. 1998 141 The studied area, Granja Florestal, Teresópolis, RESEARCH NOTE can be characterized as a secondary rain forest with poor human dwellings on the forests borders. The local population live basically on small agricul- The Occurrence of ture and hunting. Weekly searches were performed between September and March (1994-95) and in- Rhodnius prolixus Stal, 1859, cluded palm-trees, bracts of pteridophyta, bird and Naturally Infected by mammal nests, leafages and bromeliaceae. The collected insects were maintained in glass Trypanosoma cruzi in the flasks, fed through a membrane (ES Garcia et al. State of Rio de Janeiro, 1975 Rev Brasil Biol 35: 207-210) and the nymphs were allowed to moult. Seven isolates of T. cruzi Brazil (Hemiptera, were obtained through inoculation of swiss mice with the feces of the infected bugs. Axenic me- Reduviidae, Triatominae) dium derived metacyclic forms (105) from each Ana Paula Pinho, Teresa Cristina M isolate and were intraperitoneally inoculated in five swiss outbred mice weighing 18-20g. No mortal- Gonçalves*, Regina Helena ity occurred and only rare flagellates during a 2-3 Mangia**, Nédia S Nehme Russell**, day period could be observed in the fresh blood + Ana Maria Jansen/ preparations examined every other day, during two Departmento de Protozoologia *Departmento de months. Furthermore, the experimental infection Entomologia **Departmento de Bioquímica e by the isolates was stable as confirmed by the posi- Biologia Molecular, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Av. tive hemocultures made three months after the in- Brasil 4365, 21045-900 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil oculation. -

Oviposition in the Blood-Sucking Insect Rhodnius Prolixus Is Modulated by Host Odors Fabio Guidobaldi1,2* and Pablo G Guerenstein1,2

Guidobaldi and Guerenstein Parasites & Vectors (2015) 8:265 DOI 10.1186/s13071-015-0867-5 RESEARCH Open Access Oviposition in the blood-sucking insect Rhodnius prolixus is modulated by host odors Fabio Guidobaldi1,2* and Pablo G Guerenstein1,2 Abstract Background: Triatomine bugs are blood-sucking insects, vectors of Chagas disease. Despite their importance, their oviposition behavior has received relatively little attention. Some triatomines including Rhodnius prolixus stick their eggs to a substrate. It is known that mechanical cues stimulate oviposition in this species. However, it is not clear if chemical signals play a role in this behavior. We studied the role of host cues, including host odor, in the oviposition behavior of the triatomine R. prolixus. Methods: Tests were carried out in an experimental arena and stimuli consisted of a mouse or hen feathers. The number of eggs laid and the position of those eggs with respect to the stimulus source were recorded. Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Results: Both a mouse and hen feathers stimulated oviposition. In addition, hen feathers evoked a particular spatial distribution of eggs that was not observed in the case of mouse. Conclusions: We propose that volatile chemical cues from the host play a role in the oviposition behavior of triatomines that stick their eggs. Thus, host odor would stimulate and spatially guide oviposition. Keywords: Oviposition stimulation, Spatial distribution of eggs, Chagas disease, Triatomine, Hematophagous insect, Insect control, Insect monitoring Background In those cases in which optimal oviposition sites are The selection of sites for oviposition is a critical factor rare or difficult to find, female’s fitness would increase if for the survival of the offspring of an individual. -

Universidade Do Estado Da Bahia Anais Da Xxiii Jornada De Iniciação

UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DA BAHIA ANAIS DA XXIII JORNADA DE INICIAÇÃO CIENTÍFICA “UNIVERSIDADE PÚBLICA E GRATUITA: RESISTÊNCIA, PRODUÇÃO CIENTÍFICA E TRANSFORMAÇÃO SOCIAL.” Salvador, 14 a 16 de outubro de 2019. FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA Sistema de Bibliotecas da UNEB Biblioteca Edivaldo Machado Boaventura Jornada de Iniciação Científica da UNEB (23.: 2019: Salvador, BA) Anais [da] / XXIII Jornada de Iniciação Científica da UNEB: Universidade Pública e Gratuita: Resistência, Produção Científica E Transformação Social, Salvador de 14 a 16 de outubro de 2019. Salvador: EDUNEB, 2019. 635p. ISSN : 2237-6895. 1. Ensino superior - Pesquisa - Brasil - Congressos. 2. Pesquisa - Bahia - Congressos. I. Universidade do Estado da Bahia - Congressos. CDD: 378.0072 UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DA BAHIA REITORIA JOSÉ BITES DE CARVALHO VICE-REITORIA MARCELO DUARTE DANTAS ÁVILA CHEFIA DE GABINETE (CHEGAB) HILDA SILVA FERREIRA PRÓ-REITORIA DE ENSINO DE GRADUAÇÃO (PROGRAD) ELIENE MARIA DA SILVA PRÓ-REITORIA DE PESQUISA E ENSINO DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO (PPG) TÂNIA MARIA HETKOWSKI PRÓ-REITORIA DE EXTENSÃO (PROEX) ADRIANA SANTOS MARMORE LIMA PRÓ-REITORIA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO (PROAD) DANIEL DE CERQUEIRA GÓES PRÓ-REITORIA DE PLANEJAMENTO (PROPLAN) IZA ANGELICA CARVALHO DA SILVA PRÓ-REITORIA DE GESTÃO E DESENVOLVIMENTO (PGDP) LILIAN DA ENCARNAÇÃO CONCEIÇÃO PRÓ-REITORIA DE AÇÕES AFIRMATIVA (PROAF) AMELIA TEREZA SANTA ROSA MARAUX PRÓ-REITORIA DE ASSISTÊNCIA ESTUDANTIL (PRAES) ELIVÂNIA REIS DE ANDRADE ALVES PRÓ-REITORIA DE INFRAESTRUTURA (PROINFRA) FAUSTO FERREIRA COSTA GUIMARÃES UNIDADE -

Distribution and Ecological Aspects of Rhodnius Pallescens in Costa Rica

Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Vol. 101(1): 75-79, February 2006 75 Distribution and ecological aspects of Rhodnius pallescens in Costa Rica and Nicaragua and their epidemiological implications Rodrigo Zeledón/+, Francisca Marín*, Nidia Calvo**, Emperatriz Lugo*, Sonia Valle* Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad Nacional, Apartado Postal 86, Heredia, Costa Rica *Programa de Enfermedad de Chagas, Ministerio de Salud, Managua, Nicaragua **Instituto Costarricense de Investigación y Enseñanza en Nutrición y Salud, Tres Ríos, Cartago, Costa Rica In light of the Central American Initiative for the control of Chagas disease, efforts were made on the part of Costa Rican and Nicaraguan teams, working separately, to determine the present status of Rhodnius pallescens in areas close to the common border of the two countries, where the insect has appeared within the last few years. The opportunity was also used to establish whether R. prolixus, a vector present in some areas of Nicaragua, has been introduced in recent years into Costa Rica with Nicaraguan immigrants. It became evident that wild adults of R. pallescens are common visitors to houses in different towns of a wide area characterized as a humid, warm lowland, on both sides of the frontier. Up to the present, this bug has been able to colonize a small proportion of human dwellings only on the Nicaraguan side. There was strong evidence that the visitation of the adult bug to houses is related to the attraction of this species to electric lights. There were no indications of the presence of R. prolixus either in Nicaragua or in Costa Rica in this area of the Caribbean basin. -

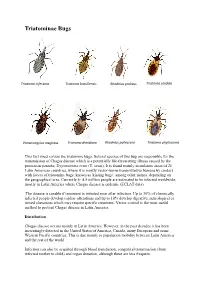

Triatominae Bugs

Triatominae Bugs Triatoma infestans Triatoma brasiliensis Rhodnius prolixus Triatoma sordida Panstrongylus megistus Triatoma dimidiata Rhodnius pallescens Triatoma phyllosoma This fact sheet covers the triatomine bugs. Several species of this bug are responsible for the transmission of Chagas disease which is a potentially life-threatening illness caused by the protozoan parasite, Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi). It is found mainly in endemic areas of 21 Latin American countries, where it is mostly vector-borne transmitted to humans by contact with faeces of triatomine bugs, known as 'kissing bugs', among other names, depending on the geographical area. Currently 4- 4.5 million people are estimated to be infected worldwide, mostly in Latin America where Chagas disease is endemic (ECLAT data). The disease is curable if treatment is initiated soon after infection. Up to 30% of chronically infected people develop cardiac alterations and up to 10% develop digestive, neurological or mixed alterations which may require specific treatment. Vector control is the most useful method to prevent Chagas disease in Latin America. Distribution Chagas disease occurs mainly in Latin America. However, in the past decades it has been increasingly detected in the United States of America, Canada, many European and some Western Pacific countries. This is due mainly to population mobility between Latin America and the rest of the world. Infection can also be acquired through blood transfusion, congenital transmission (from infected mother to child) and organ donation, although these are less frequent. Transmission In Latin America, T. cruzi parasites are mainly transmitted by contact with the faeces of infected blood-sucking triatomine bugs. These bugs, vectors that carry the parasites, typically live in the cracks of poorly-constructed homes in rural or suburban areas. -

Satellitome Analysis of Rhodnius Prolixus, One of the Main Chagas Disease Vector Species

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Satellitome Analysis of Rhodnius prolixus, One of the Main Chagas Disease Vector Species Eugenia E. Montiel 1, Francisco Panzera 2 , Teresa Palomeque 1 , Pedro Lorite 1,* and Sebastián Pita 2,* 1 Department of Experimental Biology, Genetics, University of Jaén. Paraje las Lagunillas sn., 23071 Jaén, Spain; [email protected] (E.E.M.); [email protected] (T.P.) 2 Evolutionary Genetic Section, Faculty of Science, University of the Republic, Iguá 4225, Montevideo 11400, Uruguay; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (P.L.); [email protected] (S.P.) Abstract: The triatomine Rhodnius prolixus is the main vector of Chagas disease in countries such as Colombia and Venezuela, and the first kissing bug whose genome has been sequenced and assembled. In the repetitive genome fraction (repeatome) of this species, the transposable elements represented 19% of R. prolixus genome, being mostly DNA transposon (Class II elements). However, scarce information has been published regarding another important repeated DNA fraction, the satellite DNA (satDNA), or satellitome. Here, we offer, for the first time, extended data about satellite DNA families in the R. prolixus genome using bioinformatics pipeline based on low-coverage sequencing data. The satellitome of R. prolixus represents 8% of the total genome and it is composed by 39 satDNA families, including four satDNA families that are shared with Triatoma infestans, as well as telomeric (TTAGG) and (GATA) repeats, also present in the T. infestans genome. Only three of them exceed n n 1% of the genome. Chromosomal hybridization with these satDNA probes showed dispersed signals over the euchromatin of all chromosomes, both in autosomes and sex chromosomes. -

Blood-Feeding of Rhodnius Prolixus Doi

Biomédica 2017;37:2017;37:299-302299-302 Blood-feeding of Rhodnius prolixus doi: https://doi.org/10.7705/biomedica.v34i2.3304 IMAGES IN BIOMEDICINE Blood-feeding of Rhodnius prolixus Kevin Escandón-Vargas1,2, Carlos A. Muñoz-Zuluaga1,3, Liliana Salazar3 1 Escuela de Medicina, Facultad de Salud, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia 2 Departamento de Microbiología, Facultad de Salud, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia 3 Departamento de Morfología, Facultad de Salud, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia Triatomines (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) are blood-sucking insect vectors of the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi which is the causative agent of Chagas’ disease. Rhodnius prolixus is the most epidemiologically important vector of T. cruzi in Colombia. Triatomines are regarded to be vessel-feeders as they obtain their blood meals from vertebrate hosts by directly inserting their mouthparts into vessels. Microscopic techniques are useful for visualizing and describing the morphology of biological structures. Here, we show images of the blood-feeding of R. prolixus, including some histological features by light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy of the mouthparts of R. prolixus when feeding on a laboratory mouse. Key words: Rhodnius; Triatominae; microscopy; histology. doi: https://doi.org/10.7705/biomedica.v34i2.3304 Alimentación de Rhodnius prolixus Los triatominos (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) son insectos hematófagos vectores del protozooTrypanosoma cruzi, el cual causa la enfermedad de Chagas. Rhodnius prolixus es el vector de T. cruzi de mayor importancia epidemiológica en Colombia. Para alimentarse, los triatominos introducen su probóscide directamente en los vasos sanguíneos de los huéspedes vertebrados. La microscopía es una técnica útil para visualizar y describir la morfología de estructuras biológicas.