Tales out of School.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys

William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice Volume 11 (2004-2005) Issue 2 William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law: Symposium: Attrition of Women from Article 6 the Legal Profession February 2005 Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys Ann Bartow Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl Part of the Law and Gender Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Repository Citation Ann Bartow, Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys, 11 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 221 (2005), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ wmjowl/vol11/iss2/6 Copyright c 2005 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl SOME DUMB GIRL SYNDROME: CHALLENGING AND SUBVERTING DESTRUCTIVE STEREOTYPES OF FEMALE ATTORNEYS ANN BARTOW* I. INTRODUCTION Almost every woman has had the experience of being trivialized, regarded as if she is just 'some dumb girl,' of whom few productive accomplishments can be expected. When viewed simply as 'some dumb girls,' women are treated dismissively, as if their thoughts or contributions are unlikely to be of value and are unworthy of consideration. 'Some Dumb Girl Syndrome' can arise in deeply personal spheres. A friend once described an instance of this phenomenon: When a hurricane threatened her coastal community, her husband, a military pilot, was ordered to fly his airplane to a base in the Midwest, far from the destructive reach of the impending storm. This left her alone with their two small children. -

International Design Conference in Aspen Records, 1949-2006

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pg1t6j Online items available Finding aid for the International Design Conference in Aspen records, 1949-2006 Suzanne Noruschat, Natalie Snoyman and Emmabeth Nanol Finding aid for the International 2007.M.7 1 Design Conference in Aspen records, 1949-2006 ... Descriptive Summary Title: International Design Conference in Aspen records Date (inclusive): 1949-2006 Number: 2007.M.7 Creator/Collector: International Design Conference in Aspen Physical Description: 139 Linear Feet(276 boxes, 6 flat file folders. Computer media: 0.33 GB [1,619 files]) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Founded in 1951, the International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) emulated the Bauhaus philosophy by promoting a close collaboration between modern art, design, and commerce. For more than 50 years the conference served as a forum for designers to discuss and disseminate current developments in the related fields of graphic arts, industrial design, and architecture. The records of the IDCA include office files and correspondence, printed conference materials, photographs, posters, and audio and video recordings. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English. Biographical/Historical Note The International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) was the brainchild of a Chicago businessman, Walter Paepcke, president of the Container Corporation of America. Having discovered through his work that modern design could make business more profitable, Paepcke set up the conference to promote interaction between artists, manufacturers, and businessmen. -

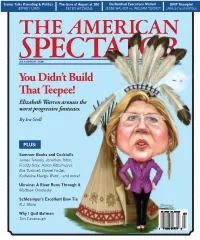

You Didn't Build That Teepee!

Trump Talks Parenting & Politics The Guns of August at 100 Do Botched Executions Matter? UKIP Triumphs! JEFFREY LORD PETER HITCHENS JESSE WALKER vs. WILLIAM TUCKER JAMES DELINGPOLE JULY/AUGUST 2014 A MONTHLY REVIEW EDITED BY R. EMMETT TYRRELL, JR. You Didn’t Build That Teepee! Elizabeth Warren arouses the worst progressive fantasies. By Ira Stoll PLUS: Summer Books and Cocktails James Taranto, Jonathan Tobin, Freddy Gray, Helen Rittelmeyer, Eve Tushnet, Daniel Foster, Katherine Mangu-Ward…and more! Ukraine: A River Runs Through It Matthew Omolesky Schlesinger’s Excellent Bow Tie R.J. Stove Why I Quit Batman Tim Cavanaugh 1 5 1 5 1 5 1 5 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 100 100 100 100 “ The best detector is not merely the one that can pick up radar from the farthest distance, although the Valentine One continues to score best.” — Autoweek Now V1 comes to a touchscreen near you. Introducing the Threat Picture You can see the arrows at work on your compatible iPhone® or AndroidTM device. Check it out… The app is free! Yo u can download V1connection, the app Where’s the radar? It’s in the Box. for free. Go to the app store on your device. When installed, the app automatically runs in Demo Mode. No need to link to V1. Analyze preloaded threat situations on three different screens: on the V1 screen, Arrow in the Box means a threat in the radar zone. on Picture, and on List. Then when you’re ready to put the Threat Picture on duty in your car, order the Bluetooth® communication module directly from us. -

One Beverly Hills Approved by Council

BEVERLYPRESS.COM INSIDE • Beverly Hills approves budget Sunny, with pg. 3 highs in the • Fire on Melrose 70s pg. 4 Volume 31 No. 23 Serving the Beverly Hills, West Hollywood, Hanock Park and Wilshire Communities June 10, 2021 WeHo calls for LASD audit One Beverly Hills approved by council n If county fails to act, city may step in n Bosse clashes with BY CAMERON KISZLA Association to audit the contracts of Mirisch on affordable all cities partnered with the LASD, housing issue The West Hollywood City which include West Hollywood. Council took action in regards to The council’s vote, which was BY CAMERON KISZLA the allegations of fraud made part of the consent calendar, comes against the Los Angeles County after the LASD was accused in a The Beverly Hills City Council Sheriff’s Department. legal filing last month of fraudu- on June 8 gave the One Beverly The council on June 7 unani- lently billing Compton, another city Hills project the necessary mously called for the Los Angeles that is contracted with the depart- approvals, but not without some County Board of Supervisors and ment, for patrolling the city less conflict between council members. the inspector general to work with See page The 4-1 vote was opposed by the California Contract Cities LASD 31 Councilman John Mirisch, who raised several issues with the pro- ject, including that more should be done to create affordable housing. rendering © DBOX for Alagem Capital Group The One Beverly Hills project includes 4.5 acres of publicly accessible Mirisch cited several pieces of evidence, including the recently botanical gardens and a 3.5-acre private garden for residents and completed nexus study from hotel guests. -

The Federal Communications Commission, Obscenity and the Chilling of Artistic Expression on Radio Airwaves

\\server05\productn\C\CAE\24-1\CAE106.txt unknown Seq: 1 15-MAY-06 13:32 YOUR REVOLUTION: THE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION, OBSCENITY AND THE CHILLING OF ARTISTIC EXPRESSION ON RADIO AIRWAVES NASOAN SHEFTEL-GOMES* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................... 192 R I. A CASE STUDY ........................................ 194 R II. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: OBSCENITY DEFINED: ONE MAN’S VULGARITY IS ANOTHER MAN’S LYRIC ........... 199 R III. BROADCAST OBSCENITY ................................ 205 R A. The Federal Communications Commission: A Notable Exception .......................................... 205 R B. Applying the FCC Test for Indecency ................. 208 R IV. “DON’T BURN THE HOUSE TO ROAST THE PIG” ........ 212 R A. The Current Landscape: The Artist Adrift ............ 212 R 1. Regulation as Government Sanctioned Censorship ................................... 212 R 2. The Artist without Recourse.................. 214 R 3. Commercial Recourse: Eminem and Sarah Jones in Sharp Contrast ...................... 218 R B. Recommendations: Legal Recourse for the “Indecent” Artist ............................................. 220 R 1. Legal Recourse: Standing for Artists.......... 221 R CONCLUSION ................................................. 226 R * Nasoan Sheftel Gomes, J.D., City University of New York School of Law 2005, Masters of Journalism (MJ), University of California at Berkeley, 1995, BA Sociology, Clark University 1993, is a law graduate with Goldfarb, Abrandt, Salzman and Kutzin in New York. The author would like to thank Professor Ruthann Robson for her supervision, guidance and keen insights during the two years within which this article was written. Thank you to Associate Professor, Rebecca Bratspies, for her assistance in interpreting the impact of Friends of the Earth v. Laidlaw upon the author’s argument. The author would also like to thank Professor Jenny Rivera for her ongoing support. -

On the Square in Oxford Since 1979. U.S

Dear READER, Service and Gratitude It is not possible to express sufficiently how thankful we at Square Books have been, and remain, for the amazing support so many of you have shown to this bookstore—for forty years, but especially now. Nor can I adequately thank the loyal, smart, devoted booksellers here who have helped us take safe steps through this unprecedented difficulty, and continue to do so, until we find our way to the other side. All have shown strength, resourcefulness, resilience, and skill that maybe even they themselves did not know they possessed. We are hearing stories from many of our far-flung independent bookstore cohorts as well as other local businesses, where, in this community, there has long been—before Amazon, before Sears—a shared knowledge regarding the importance of supporting local places and local people. My mother made it very clear to me in my early teens why we shopped at Mr. Levy’s Jitney Jungle—where Paul James, Patty Lampkin, Richard Miller, Wall Doxey, and Alice Blinder all worked. Square Books is where Slade Lewis, Sid Albritton, Andrew Pearcy, Jesse Bassett, Jill Moore, Dani Buckingham, Paul Fyke, Jude Burke-Lewis, Lyn Roberts, Turner Byrd, Lisa Howorth, Sami Thomason, Bill Cusumano, Cody Morrison, Andrew Frieman, Katelyn O’Brien, Beckett Howorth, Cam Hudson, Morgan McComb, Molly Neff, Ted O’Brien, Gunnar Ohberg, Kathy Neff, Al Morse, Rachel Tibbs, Camille White, Sasha Tropp, Zeke Yarbrough, and I all work. And Square Books is where I hope we all continue to work when we’ve found our path home-free. -

Writer, Musician, Radio Commentator, Artist

Name in English: Sandra Tsing Loh Name in Chinese: 陆赛静 [陸賽靜] Name in Pinyin: Lù Saì Jìng Gender: Female Birth Year: 1962 Birth Place: California Current location: Van Nuys, California Writer, Musician, Radio Commentator, Artist Profession(s): Writer, Performance-Artist, Radio Commentator, Musician & Composer Education: Bachelor of Science, Physics/Bachelor of Arts, Literature, 1983, California Institute of Technology; Master of Professional Writing, University of Southern California Awards: 2006, Finalist for the National Magazine Award, American Society of Magazine Editors & the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism; 2001 Distinguished Alumni Award, Caltech; 1997, Pushcart Prize for “My Father’s Chinese Wives” from Pushcart Press Contributions: Born and raised in Southern California to a Chinese father and German mother, Sandra Tsing Loh first gained notoriety with her performance art, such as playing a piano concert on an overpass of the Harbor Freeway running through Downtown Los Angeles in September 1987. Her piano and performance art have been featured in magazines such as People, GQ, Glamour, and on TV on CNN and NBC’s Tonight Show. By the 1990s she’d gained additional national fame as a respected radio commentator on NPR’s "Morning Edition" and on Ira Glass’ "This American Life." She has also been noted for writing several books including, A Year in Van Nuys, Aliens in America, Depth Takes a Holiday: Essays From Lesser Los Angeles, and a novel, If You Lived Here, You’d Be Home By Now, which was named by the Los Angeles Times as one of the 100 best fiction books of 1998. Her short stories and essays have been featured in the New York Times, Elle, Harper’s Bazaar, and Vogue. -

Tossups by Alice Gh;,\

Tossups by Alice Gh;,\. ... 1. Founded in 1970 with a staff of 35, it now employs more than 700 people and has a weekly audience of over 23 million. The self-described "media industry leader in sound gathering," its ·mission statement declares that its goal is to "work in partnership with member stations to create a more informed public." Though it was created by an act of Congress, it is not a government agency; neither is it a radio station, nor does it own any radio stations. FTP, name this provider of news and entertainment, among whose most well-known products are the programs Morning Edition and All Things Considered. Answer: National £ublic Radio . 2. He's been a nanny, an insurance officer and a telemarketer, and was a member of the British Parachute Regiment, earning medals for service in Northern Ireland and Argentina. One of his most recent projects is finding a new lead singer for the rock band INXS, while his less successful ventures include Combat Missions, The Casino, and The Restaurant. One of his best-known shows spawned a Finnish version called Diili, and shooting began recently on a spinoff starring America's favorite convict. FTP, name this godfather of reality television, the creator of The Apprentice and Survivor. Answer: Mark Burnett 3. A girl named Fern proved helpful in the second one, while Sanjay fulfilled the same role during the seventh. Cars made of paper, plastic pineapples, and plaster elephants have been key items, and participants have been compelled to eat chicken feet, a sheep's head, a kilo of caviar, and four pounds of Argentinian barbecue, although not all in the same season. -

Annual Report Fiscal Year 2015 Our Work 08

ANNUAL REPORT FISCAL YEAR 2015 OUR WORK 08 ARTIST SUPPORT 11 PUBLIC PROGRAMS 35 TRANSFORMATIVE SUPPORT 42 INSTITUTIONAL HEALTH 44 FOCUS ON THE ARTIST 45 2 “ There will always be new terrain to explore as long as there are artists willing to take risks, who tell their stories without compromise. And Sundance will be here - to provide a range of support and a creative community in which a new idea or distinctive view is championed.” ROBERT REDFORD PRESIDENT AND FOUNDER Nia DaCosta and Robert Redford, Little Woods, 2015 Directors Lab, Photo by Brandon Cruz SUNDANCE INSTITUTE ANNUAL REPORT 2015 3 WELCOME ROBERT REDFORD PRESIDENT AND FOUNDER PAT MITCHELL CHAIR, BOARD OF TRUSTEES KERI PUTNAM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR I also want to thank the nearly 750 independent artists who As we close another year spent supporting extraordinary shared their work with us last year. We supported them Sundance Institute offers an environment and opportunities The health, vitality, and diversity of the Institute’s year-round artists and sharing their work with audiences around the through our 25 residency Labs, provided direct grants for artists to take risks, experiment, and fail without fear. programs are a testament to both the independent artists world, it is my pleasure to share with you the Sundance of nearly $3 million, awarded fellowships and structured We see failure not as an end but as an essential step in the who are inspired to tell their unique stories as well as the Institute Annual Report — filled with insight into the nature mentorship, and of course celebrated and launched their road. -

August/September 2009

Published by the San Fernando Valley Audubon Society A Chapter of the National Audubon Society Aug/Sept 2009 Volume 60 No. 7 PROGRAM NOTES Olga Clarke to speak at Thursday, September 24, SFVAS General Member- ship Meeting. 7:30 p.m. TOPIC: Olga will present the birds and wildlife of Cabo San Lucas Olga Clarke, will share with us her love of nature, especially birds. A world traveler and accomplished photographer, Olga receives requests for pictures from publications all over the world. Olga has orga- nized and led natural history tours to Central and South America, Africa, India, Borneo and Southeast Asia, Australia, Hawaii, and Alaska. With her late husband, Herb, they served as guest lecturers on cruise ships, even going to Antarctica. Flashlight Walk August 23, 2009 Back by popular demand! A Family Flashlight Nature Walk at the Sepulveda Basin Wildlife Reserve will be held this summer, on Sunday, August 23 at 6:45 p.m. San Fernando Valley Audubon and the Los Angeles City Park Rangers will co-sponsor the walk. The flashlight walk is designed for experienced birdwatchers, families with kids, and adults new to bird watching. We will visit the Wildlife Area at dusk, when birds are settling in for the evening. With luck, we may see bats or an owl. Donna Timlin, SFVAS, freeing Great Blue Heron at Sepulveda Basin The walk will last about one and a half hours. Be sure to bring a flashlight. We will loan binoculars to those who do not have their own. Insect repel- lent and a light wrap are recommended. -

Journalism Awards

FORTY-NINTH 4ANNUAL 9SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB th Congratulations 49 Annual Awards for Editorial Southern California Journalism Awards Excellence in 2006 David Glovin and David Evans and Los Angeles Press Club Finalist: Magazines/Investigative A non-profit organization with 501(c)(3) status Tax ID 01-0761875 Honorary Awards “How Test Companies Fail Your Kids” 4773 Hollywood Boulevard Bloomberg Markets, December 2006 Hollywood, California 90027 for 2007 Phone: (323) 669-8081 Fax: (323) 669-8069 David Glovin and David Evans Internet: www.lapressclub.org E-mail: [email protected] THE PRESIDENT’S AWARD Finalist: Investigative Series For Impact on Media “SATs Scored in Error by Test Companies Roil Admissions Process” PRESS CLUB OFFICERS Gustavo Arellano PRESIDENT: Anthea Raymond “Ask a Mexican” Radio reporter/editor OC Weekly VICE PRESIDENT: Ezra Palmer Seth Lubove Yahoo! News THE DANIEL PEARL Award Finalist: Entertainment Feature TREASURER: Rory Johnston Freelance For Courage and Integrity in Journalism 3 “John Davis, Marvin’s Son, Feuds With Sister Over ‘Looted’ Fund” SECRETARY: Jon Beaupre Radio/TV journalist, Educator Anna Politkovskaya EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Diana Ljungaeus Journalist Chet Currier International Journalist Novaya Gazeta Finalist: Column/Commentary BOARD MEMBERS Jahan Hassan, Ekush (Bengali newspaper) THE JOSEPH M. QUINN Award Josh Kleinbaum, Los Angeles Newspaper Group For Journalistic Excellence and Distinction Michael Collins, EnviroReporter.com Eric Longabardi, TeleMedia News Prod. -

2011.ARLT101.Syllabus.Spring 2011

ARLT 101: LOS ANGELES: THE FICTION Spring 2011, SGM 123, M,W 2:00-3:50, and discussion Prof. Thomas Gustafson Office: THH 402C, ext. 0-3747, email: [email protected] Office Hours: M 10-12; T 11-12, and by appt. Course Description: Los Angeles has been mocked as a city 500 miles wide and two inches deep. It is famous for its movies and music, but critics claim that it lacks cultural depth. This course seeks to prove otherwise. The region of Southern California has a remarkably rich literary heritage extending deep into its past, and over the past two decades, Los Angeles has become a pre-eminent center of literary creativity in the United States, the home of a new generation of writers whose work address questions and concerns of special significance as we confront the problems of 21st century urban America including ethnic friction, environmental crises, social inequality, and problems associated with uprootedness and materialism. Study of the literature of this region can help perform one of the vital roles of education in a democracy and in this urban region famous for its fragmentation and the powerful allure of the image: It can teach us to listen more carefully to the rich mix of voices that compose the vox populi of Los Angeles, and thus it can help create a deeper, broader sense of our common ground. So often LA is represented in our movies and our music as a place of superficial, drive-by people: on our freeways, we pass each other by, silently, wordlessly, insulated in our cars, or we are stuck in the same jam, our mobility a dream, or we crash into each other, carelessly or in rage.