The Federal Communications Commission, Obscenity and the Chilling of Artistic Expression on Radio Airwaves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Material Art from China

^ LACMA Hosts Annual Muse ’til Midnight Event Inspired by The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China WHO: The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) hosts its annual Muse ’til Midnight event, an immersive late-night museum experience. This year’s Muse ’til Midnight draws inspiration from The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China (June 2, 2019–January 5, 2020) bringing together works from the past four decades, in which conscious material choice has become a symbol of the artists’ expression. The evening includes an exceptional musical lineup curated by independent record label Ninja Tune and internet radio pioneer dublab, featuring performances by acclaimed artists such as Actress, Octo Octa, Julianna Barwick, Yu Su, and many more. Additionally, site-specific sound and visual installations, inspired by materiality, will be on view. Performances are to take place at various locations throughout the museum. This year’s event includes after-hours access to several exciting LACMA exhibitions, including The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China; Beyond Line: The Art of Korean Writing; The Invisible Man and the Masque of Blackness; and Mary Corse: A Survey in Light. Hands on art-making activities, three performance stages, a cash bar, and food for purchase will be available during the event. Muse ‘til Midnight is presented by SHOWTIME® and Max Mara. WHEN: Saturday, September 7, 2019 7:30 pm–midnight Broad Contemporary Art Museum, Level 1 7:30 pm–midnight | Miracle Mile | Strange Loop Visuals 7:30 pm–8:30 pm | Yu Su (DJ Set) 8:30 pm–10 pm | Octo Octa (DJ Set) 10 pm–midnight | Actress (DJ Set) Broad Contemporary Art Museum, Level 2 8 pm–8:45 pm | Jeremiah Chiu (Live) 9 pm–9:45 pm | Ana Roxanne (Live) 10 pm–11 pm | Julianna Barwick (Live) 11:15 pm–midnight | Ki Oni (Live) Smidt Welcome Plaza 7:30 pm–8:45 pm | Maral (DJ Set) 8:45 pm–10 pm | HELLO DJ (DJ Set) WHERE: LACMA Smidt Welcome Plaza 5905 Wilshire Blvd. -

Physicality of the Analogue by Duncan Robinson BFA(Hons)

Physicality of the Analogue by Duncan Robinson BFA(Hons) Submitted in the fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts. 2 Signed statement of originality This Thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, it incorporates no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgment is made in the text. Duncan Robinson 3 Signed statement of authority of access to copying This Thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Duncan Robinson 4 Abstract: Inside the video player, spools spin, sensors read and heads rotate, generating an analogue signal from the videotape running through the system to the monitor. Within this electro mechanical space there is opportunity for intervention. Its accessibility allows direct manipulation to take place, creating imagery on the tape as pre-recorded signal of black burst1 without sound rolls through its mechanisms. The actual physical contact, manipulation of the tape, the moving mechanisms and the resulting images are the essence of the variable electrical space within which the analogue video signal is generated. In a way similar to the methods of the Musique Concrete pioneers, or EISENSTEIN's refinement of montage, I have explored the physical possibilities of machine intervention. I am working with what could be considered the last traces of analogue - audiotape was superseded by the compact disc and the videotape shall eventually be replaced by 2 digital video • For me, analogue is the space inside the video player. -

Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys

William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice Volume 11 (2004-2005) Issue 2 William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law: Symposium: Attrition of Women from Article 6 the Legal Profession February 2005 Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys Ann Bartow Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl Part of the Law and Gender Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Repository Citation Ann Bartow, Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys, 11 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 221 (2005), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ wmjowl/vol11/iss2/6 Copyright c 2005 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl SOME DUMB GIRL SYNDROME: CHALLENGING AND SUBVERTING DESTRUCTIVE STEREOTYPES OF FEMALE ATTORNEYS ANN BARTOW* I. INTRODUCTION Almost every woman has had the experience of being trivialized, regarded as if she is just 'some dumb girl,' of whom few productive accomplishments can be expected. When viewed simply as 'some dumb girls,' women are treated dismissively, as if their thoughts or contributions are unlikely to be of value and are unworthy of consideration. 'Some Dumb Girl Syndrome' can arise in deeply personal spheres. A friend once described an instance of this phenomenon: When a hurricane threatened her coastal community, her husband, a military pilot, was ordered to fly his airplane to a base in the Midwest, far from the destructive reach of the impending storm. This left her alone with their two small children. -

International Design Conference in Aspen Records, 1949-2006

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pg1t6j Online items available Finding aid for the International Design Conference in Aspen records, 1949-2006 Suzanne Noruschat, Natalie Snoyman and Emmabeth Nanol Finding aid for the International 2007.M.7 1 Design Conference in Aspen records, 1949-2006 ... Descriptive Summary Title: International Design Conference in Aspen records Date (inclusive): 1949-2006 Number: 2007.M.7 Creator/Collector: International Design Conference in Aspen Physical Description: 139 Linear Feet(276 boxes, 6 flat file folders. Computer media: 0.33 GB [1,619 files]) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Founded in 1951, the International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) emulated the Bauhaus philosophy by promoting a close collaboration between modern art, design, and commerce. For more than 50 years the conference served as a forum for designers to discuss and disseminate current developments in the related fields of graphic arts, industrial design, and architecture. The records of the IDCA include office files and correspondence, printed conference materials, photographs, posters, and audio and video recordings. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English. Biographical/Historical Note The International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) was the brainchild of a Chicago businessman, Walter Paepcke, president of the Container Corporation of America. Having discovered through his work that modern design could make business more profitable, Paepcke set up the conference to promote interaction between artists, manufacturers, and businessmen. -

Label ARTIST Piece Tracks/Notes Format Quantity

Label ARTIST Piece Tracks/notes Format Quantity Sire Against Me! 2 song 7" single I Was A Teenage Anarchist (acoustic) 7" vinyl 2500 Sub-pop Album Leaf There Is a Wind Featuring 2 new tracks, 2 alternate takes 12" vinyl 1000 on songs from "A Chorus of Storytellers" LP Righteous Babe Ani DiFranco live @ Bull Moose recorded live on Record Store Day at CD Bull Moose in Maine Rough Trade Arthur Russell Calling Out of Context 12 new tracks Double 12" set 2000 Rocket Science Asteroids Galaxy Tour Fun Ltd edition vinyl of album with bonus 12" 250 track "Attack of the Ghost Riders" Hopeless Avenged Sevenfold Unholy Confessions picture disc includes tracks (Eternal 12" vinyl 2000 Rest, Eternal Rest (live), Unholy Confessions Artist First/Shangri- Band of Skulls Live at Fingerprints Live EP recorded at record store CD 2000 la 12/15/2009 Fingerprints Sub-pop Beach House Zebra 2 new tracks and 2 alternate from album 12" vinyl 1500 "Teen Dream" Beastie Boys white label 12" super surprise 12" vinyl 1000 Nonesuch Black Keys Tighten Up/Howlin' For 12" vinyl contains two new songs 45 RPM 12" Single 50000 You Vinyl Eagle Rock Black Label Society Skullage Double LP look at the history of Zakk Double LP 180 Wylde and Black Label Society Gram GREEN vinyl Graveface Black Moth Super Eating Us extremely limited foil pressed double LP double LP Rainbow Jagjaguwar Bon Iver/Peter Gabriel "Come Talk To Bon Iver and Peter Gabriel cover each 7" vinyl 2000 Me"/"Flume" other. Bon Iver track is EXCLUSIVE to this release Ninja Tune Bonobo featuring "Eyes -

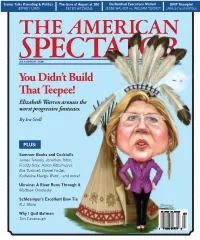

You Didn't Build That Teepee!

Trump Talks Parenting & Politics The Guns of August at 100 Do Botched Executions Matter? UKIP Triumphs! JEFFREY LORD PETER HITCHENS JESSE WALKER vs. WILLIAM TUCKER JAMES DELINGPOLE JULY/AUGUST 2014 A MONTHLY REVIEW EDITED BY R. EMMETT TYRRELL, JR. You Didn’t Build That Teepee! Elizabeth Warren arouses the worst progressive fantasies. By Ira Stoll PLUS: Summer Books and Cocktails James Taranto, Jonathan Tobin, Freddy Gray, Helen Rittelmeyer, Eve Tushnet, Daniel Foster, Katherine Mangu-Ward…and more! Ukraine: A River Runs Through It Matthew Omolesky Schlesinger’s Excellent Bow Tie R.J. Stove Why I Quit Batman Tim Cavanaugh 1 5 1 5 1 5 1 5 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 100 100 100 100 “ The best detector is not merely the one that can pick up radar from the farthest distance, although the Valentine One continues to score best.” — Autoweek Now V1 comes to a touchscreen near you. Introducing the Threat Picture You can see the arrows at work on your compatible iPhone® or AndroidTM device. Check it out… The app is free! Yo u can download V1connection, the app Where’s the radar? It’s in the Box. for free. Go to the app store on your device. When installed, the app automatically runs in Demo Mode. No need to link to V1. Analyze preloaded threat situations on three different screens: on the V1 screen, Arrow in the Box means a threat in the radar zone. on Picture, and on List. Then when you’re ready to put the Threat Picture on duty in your car, order the Bluetooth® communication module directly from us. -

One Beverly Hills Approved by Council

BEVERLYPRESS.COM INSIDE • Beverly Hills approves budget Sunny, with pg. 3 highs in the • Fire on Melrose 70s pg. 4 Volume 31 No. 23 Serving the Beverly Hills, West Hollywood, Hanock Park and Wilshire Communities June 10, 2021 WeHo calls for LASD audit One Beverly Hills approved by council n If county fails to act, city may step in n Bosse clashes with BY CAMERON KISZLA Association to audit the contracts of Mirisch on affordable all cities partnered with the LASD, housing issue The West Hollywood City which include West Hollywood. Council took action in regards to The council’s vote, which was BY CAMERON KISZLA the allegations of fraud made part of the consent calendar, comes against the Los Angeles County after the LASD was accused in a The Beverly Hills City Council Sheriff’s Department. legal filing last month of fraudu- on June 8 gave the One Beverly The council on June 7 unani- lently billing Compton, another city Hills project the necessary mously called for the Los Angeles that is contracted with the depart- approvals, but not without some County Board of Supervisors and ment, for patrolling the city less conflict between council members. the inspector general to work with See page The 4-1 vote was opposed by the California Contract Cities LASD 31 Councilman John Mirisch, who raised several issues with the pro- ject, including that more should be done to create affordable housing. rendering © DBOX for Alagem Capital Group The One Beverly Hills project includes 4.5 acres of publicly accessible Mirisch cited several pieces of evidence, including the recently botanical gardens and a 3.5-acre private garden for residents and completed nexus study from hotel guests. -

Ninja Jamm Is an App That Allows You to Remix and Reimagine Songs and Tunes in an Intuitive Way

Ninja Jamm – Frequently Asked Questions What is Ninja Jamm? Ninja Jamm is an app that allows you to remix and reimagine songs and tunes in an intuitive way. It is not an app that simply allows you to mix two tunes together – Ninja Jamm presents you all the elements of a song, broken down into easy-to-access samples which include the original compositions and more besides. Through touch and gesture controls and the intuitive Ninja Jamm interface, you are able to take an original song and reimagine it as you wish. Strip the bass and drums away and turn Eyesdown by Bonobo into a haunting piano ballad. Slow down the tempo and add reverb to the drums and bass lines to turn Take It Back by Toddla T into a down and dirty dub tune… the possibilities are endless. Ninja Jamm offers the user a way to engage with music that they love like never before. Why just consume when you can interact and create? And all for less than the price of an iTunes single. Why is Ninja Jamm a first for the music industry? Ninja Jamm is more than just an app: it’ s a brand new, interactive format for the distribution and consumption of music. It’ s a new way for people to enjoy music and a new revenue stream for artists. It will sit alongside vinyl, CD, and digital MP3 downloads in all future Ninja Tune releases. Record labels - and in particular independents record labels such as Ninja Tune - constantly seek new ways to engage their audiences and to answer the challenges met by competition from streaming services, and the increase in consumption of music via YouTube search or even file shares. -

List of Providers of Production Music*

LIST OF PROVIDERS OF PRODUCTION MUSIC* *Providers of mood music having concluded a contract with SUISA enabling it to act as a one-stop shop. Users can apply directly and exclusively to SUISA for the authorisation to use the music. Provider Label Acoris Editions T. 022 796 15 33 Moodmusicprovider by Acoris 12, rue du Grand Bay acoris@mangrove- productions.com 1220 Les Avanchets www.mangrove-productions.com Allround Music T. 041 410 22 04 Allround Music The Music library Hazy Music Swiss F. 041 410 18 04 Funtastik Music Tonework Records Zinggertorstrasse 8 G-B-W Music Unity Production Music Lib. 6006 Luzern Le Red Publishing MST Publishing Powerhouse Arcadia MSI T. 075 233 11 80 Arcadia Hollywood Music-Service-International F. 075 233 13 37 Arcadia Films Jazz line Postfach 444 [email protected] Arcadia Jingle Bank Less-is-More FL-9494 Schaan www.arcadiamusic.com ARCADIA NATIONAL Lifestyle Cinematic Loop Academy Classical Media Music Mastertrax Cosmos Library Max Music Cosmos Special Select Media music Deluxe Minimal Drones Muvico EnVogue Shorts Esovision Spot leitmotiv Galaxy Star music inc. Global Authentic Therapy Viva BMG Production Music (Germany) GmbH 1 Revolution Music Klanglobby Charlottenstraße 59 101 Dark Orchid Music Kool Kat 10117 Berlin [email protected] Absolute Music L. A. Edition Music Library GERMANY T: 0039 030 - 300 133 277 Adrenalin L.a. Riot Adrenalin Vocals Lab Hits Altitude Music Lalela Music Altitude Underscore Latin Music Collective Altitude X Faber Lemoncake Amped Library Of The Human Soul Amplitude Liquid -

Satellite Credits

Kid Koala RIC SAN (or DJ Kid Koala as he is known) is a master of pushing the SATELLITE boundaries of turntable artistry to THURSDAY, MAY 2, 7:30 PM E incredible effect. In his first visit to Carolina FRIDAY, MAY 3, 8 PM Performing Arts, he puts the imaginative style for SATURDAY, MAY 4, 8 PM which he is renowned on display with two unique CURRENT ARTSPACE + STUDIO experiences. During Satellite, audience members are seated at ROBOT DANCE PARTY stations equipped with a turntable, effects box, SATURDAY, MAY 4, 10 AM & 2 PM and a small crate of color-coded vinyl records. SUNDAY, MAY 5, 2 PM Through subtle lighting changes in the room, the CURRENT ARTSPACE + STUDIO audience is cued to play along with DJ Kid Koala, who leads them from his DJ booth. The idea for Satellite emerged from Kid Koala’s Music To Draw To series, where he would spin SATELLITE CREDITS calming music for people to draw or write Eric San, Musician / Composer to, creating a powerful creative energy in the Felix Boisvert, Musician / Turn Table room. He wanted to create an experience that Conductor was “deliberately slow, meditative, emergent, Karina Bleau, Chemical Puppeteer and creative, where everyone in the room Brian Neuman, Production / Tour Manager contributed in a small way to create the music.” carolinaperformingarts.org 55 The audience is an integral part of the show, Kid Koala is a world-renowned scratch DJ, accompanying Kid Koala to create an “ambient vinyl music producer, and an award-winning graphic novelist. orchestra,” melding their individual strains into a He has released four solo albums on Ninja Tune, including fluid body of sound. -

On the Square in Oxford Since 1979. U.S

Dear READER, Service and Gratitude It is not possible to express sufficiently how thankful we at Square Books have been, and remain, for the amazing support so many of you have shown to this bookstore—for forty years, but especially now. Nor can I adequately thank the loyal, smart, devoted booksellers here who have helped us take safe steps through this unprecedented difficulty, and continue to do so, until we find our way to the other side. All have shown strength, resourcefulness, resilience, and skill that maybe even they themselves did not know they possessed. We are hearing stories from many of our far-flung independent bookstore cohorts as well as other local businesses, where, in this community, there has long been—before Amazon, before Sears—a shared knowledge regarding the importance of supporting local places and local people. My mother made it very clear to me in my early teens why we shopped at Mr. Levy’s Jitney Jungle—where Paul James, Patty Lampkin, Richard Miller, Wall Doxey, and Alice Blinder all worked. Square Books is where Slade Lewis, Sid Albritton, Andrew Pearcy, Jesse Bassett, Jill Moore, Dani Buckingham, Paul Fyke, Jude Burke-Lewis, Lyn Roberts, Turner Byrd, Lisa Howorth, Sami Thomason, Bill Cusumano, Cody Morrison, Andrew Frieman, Katelyn O’Brien, Beckett Howorth, Cam Hudson, Morgan McComb, Molly Neff, Ted O’Brien, Gunnar Ohberg, Kathy Neff, Al Morse, Rachel Tibbs, Camille White, Sasha Tropp, Zeke Yarbrough, and I all work. And Square Books is where I hope we all continue to work when we’ve found our path home-free. -

Counting the Music Industry: the Gender Gap

October 2019 Counting the Music Industry: The Gender Gap A study of gender inequality in the UK Music Industry A report by Vick Bain Design: Andrew Laming Pictures: Paul Williams, Alamy and Shutterstock Hu An Contents Biography: Vick Bain Contents Executive Summary 2 Background Inequalities 4 Finding the Data 8 Key findings A Henley Business School MBA graduate, Vick Bain has exten sive experience as a CEO in the Phase 1 Publishers & Writers 10 music industry; leading the British Academy of Songwrit ers, Composers & Authors Phase 2 Labels & Artists 12 (BASCA), the professional as sociation for the UK's music creators, and the home of the Phase 3 Education & Talent Pipeline 15 prestigious Ivor Novello Awards, for six years. Phase 4 Industry Workforce 22 Having worked in the cre ative industries for over two decades, Vick has sat on the Phase 5 The Barriers 24 UK Music board, the UK Music Research Group, the UK Music Rights Committee, the UK Conclusion & Recommendations 36 Music Diversity Taskforce, the JAMES (Joint Audio Media in Education) council, the British Appendix 40 Copyright Council, the PRS Creator Voice program and as a trustee of the BASCA Trust. References 43 Vick now works as a free lance music industry consult ant, is a director of the board of PiPA http://www.pipacam paign.com/ and an exciting music tech startup called Delic https://www.delic.net work/ and has also started a PhD on gender diversity in the UK music industry at Queen Mary University of London. Vick was enrolled into the Music Week Women in Music Awards ‘Roll Of Honour’ and BBC Radio 4 Woman’s Hour Music Industry Powerlist.