Neodomestic American Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christians in the Movies: a Century of Saints and Sinners Bryan Polk Penn State Abington, [email protected]

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 17 Article 2 Issue 2 October 2013 10-2-2013 Christians in the Movies: A Century of Saints and Sinners Bryan Polk Penn State Abington, [email protected] Recommended Citation Polk, Bryan (2013) "Christians in the Movies: A Century of Saints and Sinners," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 17 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol17/iss2/2 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Christians in the Movies: A Century of Saints and Sinners Abstract This is a book review of Peter Dans' Christians in the Movies: A Century of Saints and Sinners (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2009). Author Notes Bryan Polk, Senior Lecturer in Religious Studies at Penn State Abington, is a graduate of Susquehanna University (B.A., Religion, 1977), Lutheran Theological Seminary, Philadelphia (M.Div., 1981), and Beaver College, now Arcadia University, Glenside, PA (M.A., English, 1995). His interests, in addition to religion and film, are in the areas of Fundamentalism in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Medieval Literature, and Biblical Studies. His publications include articles on "Jesus as a Trickster God" and "The eM dieval Image of the Hero in the Harry Potter Novels," and he has written six--unpublished--novels. He lives in Abington, Pennsylvania. This book review is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol17/iss2/2 Polk: Christians in the Movies Peter Dans has written an important book, Christians in the Movies: A Century of Saints and Sinners (2009) which brings to light a number of critical insights and presents a lucid exposition of how the Motion Picture Production Code and The Catholic Legion of Decency influenced Hollywood and American society for decades. -

Selected Highlights of Women's History

Selected Highlights of Women’s History United States & Connecticut 1773 to 2015 The Permanent Commission on the Status of Women omen have made many contributions, large and Wsmall, to the history of our state and our nation. Although their accomplishments are too often left un- recorded, women deserve to take their rightful place in the annals of achievement in politics, science and inven- Our tion, medicine, the armed forces, the arts, athletics, and h philanthropy. 40t While this is by no means a complete history, this book attempts to remedy the obscurity to which too many Year women have been relegated. It presents highlights of Connecticut women’s achievements since 1773, and in- cludes entries from notable moments in women’s history nationally. With this edition, as the PCSW celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding in 1973, we invite you to explore the many ways women have shaped, and continue to shape, our state. Edited and designed by Christine Palm, Communications Director This project was originally created under the direction of Barbara Potopowitz with assistance from Christa Allard. It was updated on the following dates by PCSW’s interns: January, 2003 by Melissa Griswold, Salem College February, 2004 by Nicole Graf, University of Connecticut February, 2005 by Sarah Hoyle, Trinity College November, 2005 by Elizabeth Silverio, St. Joseph’s College July, 2006 by Allison Bloom, Vassar College August, 2007 by Michelle Hodge, Smith College January, 2013 by Andrea Sanders, University of Connecticut Information contained in this book was culled from many sources, including (but not limited to): The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, the U.S. -

Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys

William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice Volume 11 (2004-2005) Issue 2 William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law: Symposium: Attrition of Women from Article 6 the Legal Profession February 2005 Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys Ann Bartow Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl Part of the Law and Gender Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Repository Citation Ann Bartow, Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys, 11 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 221 (2005), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ wmjowl/vol11/iss2/6 Copyright c 2005 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl SOME DUMB GIRL SYNDROME: CHALLENGING AND SUBVERTING DESTRUCTIVE STEREOTYPES OF FEMALE ATTORNEYS ANN BARTOW* I. INTRODUCTION Almost every woman has had the experience of being trivialized, regarded as if she is just 'some dumb girl,' of whom few productive accomplishments can be expected. When viewed simply as 'some dumb girls,' women are treated dismissively, as if their thoughts or contributions are unlikely to be of value and are unworthy of consideration. 'Some Dumb Girl Syndrome' can arise in deeply personal spheres. A friend once described an instance of this phenomenon: When a hurricane threatened her coastal community, her husband, a military pilot, was ordered to fly his airplane to a base in the Midwest, far from the destructive reach of the impending storm. This left her alone with their two small children. -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

LAST TRAIN HOME” by Lixin Fan

Critical Acclaim For “LAST TRAIN HOME” By Lixin Fan “The future of global capitalism, in China and elsewhere: a family tragedy in the form of a documentary, as full of anger, dignity and pathos as a play by Arthur Miller.” — A.O. Scott, The New York Times “Moving. There’s drama, misunderstanding and heartbreaking. [This family’s] pain really hits home when you think that the pants you might be wearing could have contributed to it.” — Michael O'Sullivan, The Washington Post “A stunning documentary about the modern China. This is human drama, and it is real. Fan resists the urge to embellish and simply allows . [it] to unfold in front of your eyes.” — Roger EBert, Chicago Sun-Times “Beautifully explored . an exceptional documentary. An expert, unobtrusive observer, Fan disappears inside his own film and allows us to get completely inside his subjects’ lives.” — Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times “A miniature masterpiece of documentary observation.” — Ty Burr, Boston Globe “Last Train Home might just break your heart.” — MSNBC.com “Today Show” Best Bets “This is essential viewing for understanding our world.” — Lisa Schwarzbaum, Entertainment Weekly “An incredibly powerful story that should be seen and discussed around the world.” — Kristin McCracken, The Huffington Post “Chinese-Canadian director Lixin Fan presents the human cost of China's economic rise in terms any parent or child can understand.” — Colin Covert, Minneapolis Star Tribune “A remarkable documentary. Gorgeously composed shots.” — G. Allen Johnson, San Francisco Chronicle “A moving and near-perfect piece of art. Do not miss Last Train Home. [It] is not a travelogue, a polemic or a history lesson, but simply a story of people, told with elegance and care. -

International Design Conference in Aspen Records, 1949-2006

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pg1t6j Online items available Finding aid for the International Design Conference in Aspen records, 1949-2006 Suzanne Noruschat, Natalie Snoyman and Emmabeth Nanol Finding aid for the International 2007.M.7 1 Design Conference in Aspen records, 1949-2006 ... Descriptive Summary Title: International Design Conference in Aspen records Date (inclusive): 1949-2006 Number: 2007.M.7 Creator/Collector: International Design Conference in Aspen Physical Description: 139 Linear Feet(276 boxes, 6 flat file folders. Computer media: 0.33 GB [1,619 files]) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Founded in 1951, the International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) emulated the Bauhaus philosophy by promoting a close collaboration between modern art, design, and commerce. For more than 50 years the conference served as a forum for designers to discuss and disseminate current developments in the related fields of graphic arts, industrial design, and architecture. The records of the IDCA include office files and correspondence, printed conference materials, photographs, posters, and audio and video recordings. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English. Biographical/Historical Note The International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) was the brainchild of a Chicago businessman, Walter Paepcke, president of the Container Corporation of America. Having discovered through his work that modern design could make business more profitable, Paepcke set up the conference to promote interaction between artists, manufacturers, and businessmen. -

Game Changer

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 GAME CHANGER HOW COACH BUDDY TEEVENS ’79 TURNED LOSERS INTO CHAMPIONS—AND TRANSFORMED THE GAME OF FOOTBALL FOREVER FIVE DOLLARS H W’ P B B FINE HANDCRAFTED VERMONT FURNITURE CELEBRATING 4 5 YEARS OF CRAFTSMANSHIP E E L L C C 5 T G, W, VT 802.457.2600 23 S M S, H, NH 603.643.0599 NH @ . . E THETFORD, VT FLAGSHIP SHOWROOM + WORKSHOP • S BURLINGTON, VT • HANOVER, NH • CONCORD, NH NASHUA, NH • BOSTON, MA • NATICK, MA • W HARTFORD, CT • PHILADELPHIA, PA POMPY.COM • 800.841.6671 • We Offer National Delivery S . P . dartmouth_alum_Aug 2018-5.indd 1 7/22/18 10:23 PM Africa’s Wildlife Inland Sea of Japan Imperial Splendors of Russia Journey to Southern Africa Trek to the Summit with Dirk Vandewalle with Steve Ericson with John Kopper with DG Webster of Mt. Kilimanjaro March 17–30, 2019 May 22–June 1, 2019 September 11–20, 2019 October 27–November 11, 2019 with Doug Bolger and Celia Chen ’78 A&S’94 Zimbabwe Family Safari Apulia Ancient Civilizations: Vietnam and Angkor Wat December 7–16, 2019 and Victoria Falls with Ada Cohen Adriatic and Aegean Seas with Mike Mastanduno Faculty TBD June 5–13, 2019 with Ron Lasky November 5–19, 2019 Discover Tasmania March 18–29, 2019 September 15–23, 2019 with John Stomberg Great Journey Tanzania Migration Safari January 8–22, 2020 Caribbean Windward Through Europe Tour du Montblanc with Lisa Adams MED’90 Islands—Le Ponant with John Stomberg with Nancy Marion November 6–17, 2019 Mauritius, Madagascar, with Coach Buddy Teevens ’79 June 7–17, 2019 September 15–26, 2019 -

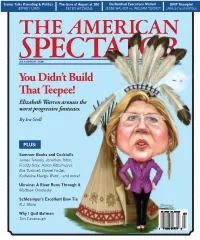

You Didn't Build That Teepee!

Trump Talks Parenting & Politics The Guns of August at 100 Do Botched Executions Matter? UKIP Triumphs! JEFFREY LORD PETER HITCHENS JESSE WALKER vs. WILLIAM TUCKER JAMES DELINGPOLE JULY/AUGUST 2014 A MONTHLY REVIEW EDITED BY R. EMMETT TYRRELL, JR. You Didn’t Build That Teepee! Elizabeth Warren arouses the worst progressive fantasies. By Ira Stoll PLUS: Summer Books and Cocktails James Taranto, Jonathan Tobin, Freddy Gray, Helen Rittelmeyer, Eve Tushnet, Daniel Foster, Katherine Mangu-Ward…and more! Ukraine: A River Runs Through It Matthew Omolesky Schlesinger’s Excellent Bow Tie R.J. Stove Why I Quit Batman Tim Cavanaugh 1 5 1 5 1 5 1 5 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 100 100 100 100 “ The best detector is not merely the one that can pick up radar from the farthest distance, although the Valentine One continues to score best.” — Autoweek Now V1 comes to a touchscreen near you. Introducing the Threat Picture You can see the arrows at work on your compatible iPhone® or AndroidTM device. Check it out… The app is free! Yo u can download V1connection, the app Where’s the radar? It’s in the Box. for free. Go to the app store on your device. When installed, the app automatically runs in Demo Mode. No need to link to V1. Analyze preloaded threat situations on three different screens: on the V1 screen, Arrow in the Box means a threat in the radar zone. on Picture, and on List. Then when you’re ready to put the Threat Picture on duty in your car, order the Bluetooth® communication module directly from us. -

One Beverly Hills Approved by Council

BEVERLYPRESS.COM INSIDE • Beverly Hills approves budget Sunny, with pg. 3 highs in the • Fire on Melrose 70s pg. 4 Volume 31 No. 23 Serving the Beverly Hills, West Hollywood, Hanock Park and Wilshire Communities June 10, 2021 WeHo calls for LASD audit One Beverly Hills approved by council n If county fails to act, city may step in n Bosse clashes with BY CAMERON KISZLA Association to audit the contracts of Mirisch on affordable all cities partnered with the LASD, housing issue The West Hollywood City which include West Hollywood. Council took action in regards to The council’s vote, which was BY CAMERON KISZLA the allegations of fraud made part of the consent calendar, comes against the Los Angeles County after the LASD was accused in a The Beverly Hills City Council Sheriff’s Department. legal filing last month of fraudu- on June 8 gave the One Beverly The council on June 7 unani- lently billing Compton, another city Hills project the necessary mously called for the Los Angeles that is contracted with the depart- approvals, but not without some County Board of Supervisors and ment, for patrolling the city less conflict between council members. the inspector general to work with See page The 4-1 vote was opposed by the California Contract Cities LASD 31 Councilman John Mirisch, who raised several issues with the pro- ject, including that more should be done to create affordable housing. rendering © DBOX for Alagem Capital Group The One Beverly Hills project includes 4.5 acres of publicly accessible Mirisch cited several pieces of evidence, including the recently botanical gardens and a 3.5-acre private garden for residents and completed nexus study from hotel guests. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Voleine Amilcar 415

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Voleine Amilcar 415-356-8383 x 244 [email protected] Mary Lugo 770-623-8190 [email protected] Cara White 843-881-1480 [email protected] For downloadable images, visit pbs.org/pressroom/ THE HOUSE I LIVE IN PREMIERES ON INDEPENDENT LENS ON MONDAY, APRIL 8, 2013 “I’d hate to imply that it’s your civic duty to see The House I Live In, but guess what — it is.” — Ty Burr, The Boston Globe (San Francisco, CA) — Winner of the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival, Eugene Jarecki’s The House I Live In builds a compelling case for the complete failure of America’s war on drugs. For the past forty years, the war on drugs has resulted in more than 45 million arrests, one trillion dollars in government spending, and America’s role as the world’s largest jailer. Yet for all that, drugs are cheaper, purer, and more available than ever. Filmed in more than twenty states, The House I Live In captures heart-wrenching stories from those on the front lines — from the dealer to the grieving mother, the narcotics officer to the senator, the inmate to the federal judge — and offers a penetrating look at the profound human rights implications of America’s longest war. The House I Live In premieres on Independent Lens, hosted by Stanley Tucci, on Monday, April 8, 2013 at 10 PM on PBS (check local listings). The film recognizes drug abuse as a matter of public health, and investigates the tragic errors and shortcomings that have resulted from framing it as an issue for law enforcement. -

American Women Writers, Visual Vocabularies, and the Lives of Literary Regionalism Katherine Mary Bloomquist Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Winter 1-1-2012 American Women Writers, Visual Vocabularies, and the Lives of Literary Regionalism Katherine Mary Bloomquist Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Bloomquist, Katherine Mary, "American Women Writers, Visual Vocabularies, and the Lives of Literary Regionalism" (2012). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 997. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/997 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of English Dissertation Examination Committee: Vivian Pollak, Chair Ruth Bohan Anca Parvulescu Daniel Shea Akiko Tsuchiya Rafia Zafar American Women Writers, Visual Vocabularies, and the Lives of Literary Regionalism by Katherine Mary Bloomquist A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2012 Saint Louis, Missouri © Copyright 2012 by Katherine Mary Bloomquist All rights reserved. Table of Contents List of Figures iii Acknowledgements iv Dissertation Abstract v Introduction: 1 Of Maps and Memoirs Chapter 1: 30 Self and Other Portraits: Sarah Orne Jewett’s “A White Heron” as Human Documents Chapter 2: 79 As If They Had a History: Documenting the Things Named in Willa Cather’s Regional Fiction Chapter 3: 137 In Place of Picture-Postcards: “Some Measure of Privacy” in Ann Petry’s Wheeling Chapter 4: 190 “Some Kind of a Writin’ Person”: Regionalism’s Unfinished Women Writers Bibliography 245 ii List of Figures Figure 1: 29 Cover Image of The Local Colorists: American Short Stories 1857-1900, ed. -

The Federal Communications Commission, Obscenity and the Chilling of Artistic Expression on Radio Airwaves

\\server05\productn\C\CAE\24-1\CAE106.txt unknown Seq: 1 15-MAY-06 13:32 YOUR REVOLUTION: THE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION, OBSCENITY AND THE CHILLING OF ARTISTIC EXPRESSION ON RADIO AIRWAVES NASOAN SHEFTEL-GOMES* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................... 192 R I. A CASE STUDY ........................................ 194 R II. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: OBSCENITY DEFINED: ONE MAN’S VULGARITY IS ANOTHER MAN’S LYRIC ........... 199 R III. BROADCAST OBSCENITY ................................ 205 R A. The Federal Communications Commission: A Notable Exception .......................................... 205 R B. Applying the FCC Test for Indecency ................. 208 R IV. “DON’T BURN THE HOUSE TO ROAST THE PIG” ........ 212 R A. The Current Landscape: The Artist Adrift ............ 212 R 1. Regulation as Government Sanctioned Censorship ................................... 212 R 2. The Artist without Recourse.................. 214 R 3. Commercial Recourse: Eminem and Sarah Jones in Sharp Contrast ...................... 218 R B. Recommendations: Legal Recourse for the “Indecent” Artist ............................................. 220 R 1. Legal Recourse: Standing for Artists.......... 221 R CONCLUSION ................................................. 226 R * Nasoan Sheftel Gomes, J.D., City University of New York School of Law 2005, Masters of Journalism (MJ), University of California at Berkeley, 1995, BA Sociology, Clark University 1993, is a law graduate with Goldfarb, Abrandt, Salzman and Kutzin in New York. The author would like to thank Professor Ruthann Robson for her supervision, guidance and keen insights during the two years within which this article was written. Thank you to Associate Professor, Rebecca Bratspies, for her assistance in interpreting the impact of Friends of the Earth v. Laidlaw upon the author’s argument. The author would also like to thank Professor Jenny Rivera for her ongoing support.