Introductions to Heritage Assets: Hermitages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hove and the Great

H o v e a n d t h e Gre a t Wa r A RECORD AND A R E VIE W together with the R oll o f Ho n o u r and Li st o f D i sti n c tio n s By H . M . WALBROOK ’ Im ied una er toe a u fbority cftfie Hov e Wa r Memorial Com m ittee Hove Sussex Th e Cliftonville Press 1 9 2 0 H o v e a n d t h e Gre a t Wa r A RECORD AND A REVIEW together with the R o ll o f Ho n o u r and Li st o f D i sti n c tio n s BY H . M . WALBROOK ’ In ned u nner toe a u tbority oftbe Have Wa r Memoria l Comm ittee Hove Sussex The Cliftonville Press 1 9 2 0 the Powers militant That stood for Heaven , in mighty quadrate joined Of union irresistible , moved on In silence their bright legions, to the sound Of instrumental harmony, that breathed Heroic ardour to adventurous deeds, Under their godlike leaders, in the cause O f ” God and His Messiah . J oan Milton. Fore word HAVE been asked to write a “ Foreword to this book ; personally I think the book speaks for itself. Representations have been ’ made from time to time that a record o fHove s share in the Great War should be published, and the idea having been put before the public meeting of the inhabitants called in April last to consider the question of a War Memorial , the publication became part, although a very minor part, of the scheme . -

FY12 Statbook SWK1 Dresden V02.Xlsx Bylea Tuitions Paid in FY12 by Vermont Districts to Out-Of-State Page 2 Public and Independent Schools for Regular Education

Tuitions Paid in FY12 by Vermont Districts to Out-of-State Page 1 Public and Independent Schools for Regular Education LEA id LEA paying tuition S.U. Grade School receiving tuition City State FTE Tuition Tuition Paid Level 281.65 Rate 3,352,300 T003 Alburgh Grand Isle S.U. 24 7 - 12 Northeastern Clinton Central School District Champlain NY 19.00 8,500 161,500 Public T021 Bloomfield Essex North S.U. 19 7 - 12 Colebrook School District Colebrook NH 6.39 16,344 104,498 Public T021 Bloomfield 19 7 - 12 North Country Charter Academy Littleton NH 1.00 9,213 9,213 Public T021 Bloomfield 19 7 - 12 Northumberland School District Groveton NH 5.00 12,831 64,155 Public T035 Brunswick Essex North S.U. 19 7 - 12 Colebrook School District Colebrook NH 1.41 16,344 23,102 Public T035 Brunswick 19 7 - 12 Northumberland School District Groveton NH 1.80 13,313 23,988 Public T035 Brunswick 19 7 - 12 White Mountain Regional School District Whitefiled NH 1.94 13,300 25,851 Public T048 Chittenden Rutland Northeast S.U. 36 7 - 12 Kimball Union Academy Meriden NH 1.00 12,035 12,035 Private T048 Chittenden 36 7 - 12 Lake Mary Preparatory School Lake Mary FL 0.50 12,035 6,018 Private T054 Coventry North Country S.U. 31 7 - 12 Stanstead College Stanstead QC 3.00 12,035 36,105 Private T056 Danby Bennington - Rutland S.U. 06 7 - 12 White Mountain School Bethlehem NH 0.83 12,035 9,962 Private T059 Dorset Bennington - Rutland S.U. -

The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions

Scholars Crossing History of Global Missions Center for Global Ministries 2009 The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_hist Recommended Citation Fanning, Don, "The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions" (2009). History of Global Missions. 3. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_hist/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Global Ministries at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in History of Global Missions by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Middle Ages 500-1000 1 3 The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions AD 500—1000 Introduction With the endorsement of the Emperor and obligatory church membership for all Roman citizens across the empire, Roman Christianity continued to change the nature of the Church, in stead of visa versa. The humble beginnings were soon forgotten in the luxurious halls and civil power of the highest courts and assemblies of the known world. Who needs spiritual power when you can have civil power? The transition from being the persecuted to the persecutor, from the powerless to the powerful with Imperial and divine authority brought with it the inevitable seeds of corruption. Some say that Christianity won the known world in the first five centuries, but a closer look may reveal that the world had won Christianity as well, and that, in much less time. The year 476 usually marks the end of the Christian Roman Empire in the West. -

Preaching by Thirteenth-Century Italian Hermits

PREACHING BY THIRTEENTH-CENTURY ITALIAN HERMITS George Ferzoco (University of Leicester) It is impossible to say what a hermit is with great precision.1 In the realm of the medieval church, any consultation of that great body of definitions to be found in canonical or legislative texts shows us very little indeed. For example, we know that hermits could own property, and, according to Hostiensis, that they could make wills. Bernard of Parma's gloss briefly addresses the question of whether a hermit can be elected abbot of a monastery. The gloss of Gratian by Johannes Teutonicus says that "solitanus" means "heremiticus", and one would assume that the inverse would hold true.2 Aban doning the realm of canon law, one does find something more helpful in the greatest legislative book for Western monks, the Regula Benedicti. Here, the Rule begins with a definition of four types of monks: two are good, and two are bad. The bad ones are the sarabaites—those who live in community but follow no rule— and the gyrovagues, who travel around continually and are, in Benedict's words, "slaves to their own wills and gross appetites".3 1 Giles Constable's study on hermits in the twelfth century shows the great ambiguity in defining the eremitical life. See Giles Constable, "Eremitical Forms of Monastic Life," in Monks, Hermits and Crusaders in Medieval Europe, Collected Studies Series 273 (London, 1988) 239-64, at 240-1. See also Jean Leclercq, "'Eremus' et 'eremita'. Pour l'histoire du vocabulaire de la vie solitaire," Colùctanea Ordinis Cisteräensium Reformatorum 25 (1963) 8-30. -

Women and Men Entering Religious Life: the Entrance Class of 2018

February 2019 Women and Men Entering Religious Life: The Entrance Class of 2018 Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate Georgetown University Washington, DC Women and Men Entering Religious Life: The Entrance Class of 2018 February 2019 Mary L. Gautier, Ph.D. Hellen A. Bandiho, STH, Ed.D. Thu T. Do, LHC, Ph.D. Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 Major Findings ................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Part I: Characteristics of Responding Institutes and Their Entrants Institutes Reporting New Entrants in 2018 ..................................................................................... 7 Gender ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Age of the Entrance Class of 2018 ................................................................................................. 8 Country of Birth and Age at Entry to United States ....................................................................... 9 Race and Ethnic Background ........................................................................................................ 10 Religious Background .................................................................................................................. -

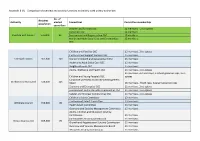

Comparison of Overview and Scrutiny Functions at Similarly Sized Unitary Authorities

Appendix B (4) – Comparison of overview and scrutiny functions at similarly sized unitary authorities No. of Resident Authority elected Committees Committee membership population councillors Children and Families OSC 12 members + 2 co-optees Corporate OSC 12 members Cheshire East Council 378,800 82 Environment and Regeneration OSC 12 members Health and Adult Social Care and Communities 15 members OSC Children and Families OSC 15 members, 2 co-optees Customer and Support Services OSC 15 members Cornwall Council 561,300 123 Economic Growth and Development OSC 15 members Health and Adult Social Care OSC 15 members Neighbourhoods OSC 15 members Adults, Wellbeing and Health OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees 21 members, 4 church reps, 3 school governor reps, 2 co- Children and Young People's OSC optees Corporate Overview and Scrutiny Management Durham County Council 523,000 126 Board 26 members, 4 faith reps, 3 parent governor reps Economy and Enterprise OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Environment and Sustainable Communities OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Safeter and Stronger Communities OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Children's Select Committee 13 members Environment Select Committee 13 members Wiltshere Council 496,000 98 Health Select Committee 13 members Overview and Scrutiny Management Committee 15 members Adults, Children and Education Scrutiny Commission 11 members Communities Scrutiny Commission 11 members Bristol City Council 459,300 70 Growth and Regeneration Scrutiny Commission 11 members Overview and Scrutiny Management Board 11 members Resources -

Give Children a Love for the Rosary Why Do Catholics Baptize Infants?

Helping our children grow in their Catholic faith. October 2017 St. Martin of Tours Parish and School Jason Fightmaster, Principal Laurie Huff, Director of Religious Education Give children a love for the Rosary Teaching children how to pray the together in a favorite spot in your Rosary can be one of the most home, light a candle, play calming inuential and long-lasting prayer music, or do whatever you like to St. Anthony Mary Claret habits you give them. make this time feel special and Consider these ideas for sacred. St. Anthony Claret helping children learn Start small and let it grow. If the was born in Spain to love the Rosary: Rosary is new to your family, in 1807 to a poor Share what you introduce the full prayer cloth weaver. He value about the by teaching the was ordained a Rosary. Some components. For priest in Catalonia people love the example, practice and in 1849, he calming rhythm of making the Sign founded the the Rosary prayers. of the Cross and Claretian order Others enjoy rehearse the shortly before becoming the meditating on Jesus’ individual archbishop of Cuba. He served as life, death, Resurrection prayers. confessor to Queen Isabella II and and Ascension described Consider using was exiled with her. He defended in the mysteries. Still the “call and the doctrine of infallibility at the others enjoy the idea of response” First Vatican Council. He also had praying a centuries old prayer. method, in which a the gifts of prophecy and healing. Help children to see what you nd leader begins a prayer and the He is the patron of textile weavers. -

Anthony the Hermit

View from the Pew Aug 2013 Kevin McCue Anthony the Hermit One of the stained glass windows I find myself gazing at frequently from the back of St. Louis is that of a Priest or Friar, clad in what appears to be a brown Franciscan robe, kneeling before a skull perched above an open book. His eyes are cast upward, his hands are clasped, and he is deep in prayer. The Franciscan habit is something I am quite familiar with as my beloved twin Uncles: Adrian and Julien Riester, were Brothers of the Franciscan Minor Order. My Uncles were truly pious men, and as a child, when they appeared gliding slowly and purposefully up the driveway of my parent’s house, they seemed otherworldly in their flowing brown habits. They were identical twins, born on the same day. However, they literally created a worldwide sensation when the both passed away, returned to The Lord, on the same day: June 1st, 2011! As they were both shy, somewhat reclusive men of God, I think they would have been embarrassed by all the fuss! And speaking of reclusive, it turns out that the image in the stained glass window is that of Saint Anthony the Hermit, also known as Anthony of Lerins and as The Father of Monks—a Christian saint. The Church celebrates his life on January 17th as the founder of Christian Monasticism. His is a most interesting tale: he was born around 251AD. His parents were wealthy, and left him a large inheritance. However, like St. Francis, he was deeply moved by The Gospel of Matthew 19:21, where Jesus instructed the young man to sell what he had, give it to the poor, and come follow him. -

Northumberland Coast Designation History

DESIGNATION HISTORY SERIES NORTHUMBERLAND COAST AONB Ray Woolmore BA(Hons), MRTPI, FRGS December 2004 NORTHUMBERLAND COAST AONB Origin 1. The Government first considered the setting up of National Parks and other similar areas in England and Wales when, in 1929, the Prime Minister, Ramsay Macdonald, established a National Park Committee, chaired by the Rt. Hon. Christopher Addison MP, MD. The “Addison” Committee reported to Government in 1931, and surprisingly, the Report1 showed that no consideration had been given to the fine coastline of Northumberland, neither by witnesses to the Committee, nor by the Committee itself. The Cheviot, and the moorland section of the Roman Wall, had been put forward as National Parks by eminent witnesses, but not the unspoilt Northumberland coastline. 2. The omission of the Northumberland coastline from the 1931 Addison Report was redressed in 1945, when John Dower, an architect/planner, commissioned by the Wartime Government “to study the problems relating to the establishment of National Parks in England and Wales”, included in his report2, the Northumberland Coast (part) in his Division C List: “Other Amenity Areas NOT suggested as National Parks”. Dower had put forward these areas as areas which although unlikely to be found suitable as National Parks, did deserve and require special concern from planning authorities “in order to safeguard their landscape beauty, farming use and wildlife, and to increase appropriately their facilities for open-air recreation”. A small-scale map in the Report, (Map II page 12), suggests that Dower’s Northumberland Coast Amenity Area stretched southwards from Berwick as a narrow coastal strip, including Holy Island, to Alnmouth. -

Paul the Hermit, H. Priscilla, Ma. Antony of Egypt, Ab. Peter's Chair At

th Wednesday, January 17 Antony of Egypt, Ab. 8:00 AM +Florence Gorlick (B.D.), By Family th Thursday, January 18 Peter’s Chair at Antioch 8:00 AM No Mass Sunday, January 14, 2018 10:00 AM Seniors Meeting - Refreshments Second Sunday in Ordinary Time 8:00 AM Holy Mass / Contemporary Group th Friday, January 19 Lector: Lauren Lightcap Marius, Martha and Sons, M. 9:00 AM Coffee Hour 8:00 AM +Dorothy Ratke (B.D.), 9:30 AM School of Christian Living (SOCL) By Susan Goodrich and Family 9:30 AM Adult Bible Class 11:00 AM Deacon Service / Contemporary Group th Lector: Natalie Jennings Saturday, January 20 Fabian, Bp. & Sebastian M. Flowers at the Main Altar are given to the Glory 8:00 AM Mass of the Day of God and in Loving Memory of Husband 1:00 PM Confirmation Class Sigmund and Son Thomas Nowak (Annv), By Ceil Nowak and Family Sunday, January 21, 2018 Monday, January 15th Third Sunday in Ordinary Time Paul the Hermit, H. 7:30 AM Harmonia Choir Practice 8:00 AM +Louise Marszalkowski, 8:00 AM Holy Mass By Estate Lector: Tammy Lightcap 8:00 AM Bingo Kitchen Workers Report 9:00 AM Coffee Hour Hosts - Youth Association 9:00 AM Bingo Team #1 Report 9:30 AM Youth Association Meeting 11:30 AM Bingo 9:30 AM Adult Bible Class 7:00 PM Harmonia Choir Practice 10:30 AM Harmonia Choir Practice 11:00 AM Holy Mass Tuesday, January 16th Lector: Christina Giczkowski Priscilla, Ma. 12:15 PM Senior Christmas Dinner 8:00 AM No Mass 6:00 PM Parish Bowling League 10:30 to Noon – Prayer Shawl (No Evening session) JANUARY PARISH COMMITTEE COUNTERS THANK YOU 8:00 AM Cindy Pecynski & Chuch Daehn The family of Regina Kosek would 11:00 AM Frank Russo & Beverly Basinski like to thank Bishop John and Fr. -

Northumberland Coast Path

Walking Holidays in Britain’s most Beautiful Landscapes Northumberland Coast Path The Northumberland Coast is best known for its sweeping beaches, imposing castles, rolling dunes, high rocky cliffs and isolated islands. Amidst this striking landscape is the evidence of an area steeped in history, covering 7000 years of human activity. A host of conservation sites, including two National Nature Reserves testify to the great variety of wildlife and habitats also found on the coast. The 64miles / 103km route follows the coast in most places with an inland detour between Belford and Holy Island. The route is generally level with very few climbs. Mickledore - Walking Holidays to Remember 1166 1 Walking Holidays in Britain’s most Beautiful Landscapes t: 017687 72335 e: [email protected] w: www.mickledore.co.uk Summary on the beach can get tiring – but there’s one of the only true remaining Northumberland Why do this walk? usually a parallel path further inland. fishing villages, having changed very little in over • A string of dramatic castles along 100 years. It’s then on to Craster, another fishing the coast punctuate your walk. How Much Up & Down? Not very much village dating back to the 17th century, famous for • The serene beauty of the wide open at all! Most days are pretty flat. The high the kippers produced in the village smokehouse. bays of Northumbrian beaches are point of the route, near St Cuthbert’s Just beyond Craster, the route reaches the reason enough themselves! Cave, is only just over 200m. imposing ruins of Dunstanburgh Castle, • Take an extra day to cross the tidal causeway to originally built in the 14th Century by Holy Island with Lindisfarne Castle and Priory. -

Tuitions Paid in FY2013 by Vermont Districts to Out-Of-State Public And

Tuitions Paid in FY2013 by Vermont Districts to Out-of-State Page 1 Public and Independent Schools for Regular Education LEA id LEA paying tuition S.U. Grade School receiving tuition City State FTE Tuition Tuition Paid Level 331.67 Rate 3,587,835 T003 Alburgh Grand Isle S.U. 24 Sec Clinton Community College Champlain NY 1.00 165 165 College T003 Alburgh 24 Sec Northeastern Clinton Central School District Champlain NY 14.61 9,000 131,481 Public T003 Alburgh 24 Sec Paul Smith College Paul Smith NY 2.00 120 240 College T010 Barnet Caledonia Central S.U. 09 Sec Haverhill Cooperative Middle School Haverhill NH 0.50 14,475 7,238 Public T021 Bloomfield Essex North S.U. 19 Sec Colebrook School District Colebrook NH 9.31 16,017 149,164 Public T021 Bloomfield 19 Sec Groveton High School Northumberland NH 3.96 14,768 58,547 Public T021 Bloomfield 19 Sec Stratford School District Stratford NH 1.97 13,620 26,862 Public T035 Brunswick Essex North S.U. 19 Sec Colebrook School District Colebrook NH 1.50 16,017 24,026 Public T035 Brunswick 19 Sec Northumberland School District Groveton NH 2.00 14,506 29,011 Public T035 Brunswick 19 Sec White Mountain Regional School District Whitefiled NH 2.38 14,444 34,409 Public T036 Burke Caledonia North S.U. 08 Sec AFS-USA Argentina 1.00 12,461 12,461 Private T041 Canaan Essex North S.U. 19 Sec White Mountain Community College Berlin NH 39.00 150 5,850 College T048 Chittenden Rutland Northeast S.U.