County and Community in Medieval England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Medicine in the City of London

[From Fabricios ab Aquapendente: Opere chirurgiche. Padova, 1684] ANNALS OF MEDICAL HISTORY Third Series, Volume III January, 1941 Number 1 HISTORY OF MEDICINE IN THE CITY OF LONDON By SIR HUMPHRY ROLLESTON, BT., G.C.V.O., K.C.B. HASLEMERE, ENGLAND HET “City” of London who analysed Bald’s “Leech Book” (ca. (Llyn-din = town on 890), the oldest medical work in Eng the lake) lies on the lish and the textbook of Anglo-Saxon north bank of the leeches; the most bulky of the Anglo- I h a m e s a n d Saxon leechdoms is the “Herbarium” stretches north to of that mysterious personality (pseudo-) Finsbury, and east Apuleius Platonicus, who must not be to west from the confused with Lucius Apuleius of Ma- l ower to Temple Bar. The “city” is daura (ca. a.d. 125), the author of “The now one of the smallest of the twenty- Golden Ass.” Payne deprecated the un nine municipal divisions of the admin due and, relative to the state of opin istrative County of London, and is a ion in other countries, exaggerated County corporate, whereas the other references to the imperfections (super twenty-eight divisions are metropolitan stitions, magic, exorcisms, charms) of boroughs. Measuring 678 acres, it is Anglo-Saxon medicine, as judged by therefore a much restricted part of the present-day standards, and pointed out present greater London, but its medical that the Anglo-Saxons were long in ad history is long and of special interest. vance of other Western nations in the Of Saxon medicine in England there attempt to construct a medical litera is not any evidence before the intro ture in their own language. -

Nottingham Investigation Opening Statement

1.Introduction - Counsel 1. Good morning Chair and Panel. I am Patrick Sadd, lead Counsel to the Nottinghamshire investigations. Next to me sit Paul Livingston, Olinga Tahzib and Imogen Egan junior counsel to this investigation. 2. Today the Inquiry begins the substantive public hearings into Nottinghamshire Investigation. In line with the published scope of the investigation we will be looking at the nature and extent of, and institutional responses to the sexual abuse of children in the care of the councils. 3. The Nottinghamshire investigation is one of 13 investigations so far launched by the Inquiry and is one of three investigations looking at the response of local authorities - the others being Rochdale which was heard in 2017 and Lambeth due to be heard in late 2019. 4. In the early part of this decade, local media in Nottinghamshire began to report that a number of people who had spent time in children’s homes in the 1970s-1990s alleged that they had been sexually abused by care staff at these homes. A growing number of allegations continued to be reported and in 2011, Nottinghamshire Police opened a dedicated investigation into allegations relating to the Beechwood complex and other homes in the City area - operation Daybreak. Subsequently, Operations 1 Xeres and Equinox were launched, to include homes in the Nottinghamshire County area. 5. In 2014 and 2015 media reporting began to focus on the apparent lack of any visible outcome from the investigations or action from the local Councils. 6. In response to public demand for action, Nottinghamshire County Council and Nottingham City Council had announced an Independent Review. -

A Guide to the Historic Counties for the Press and Media

Our counties matter! A guide to the historic counties for the Press and Media Be County-Wise and get to know the Historic Counties county-wise.org.uk First Edition Visit county-wise.org.uk for more information about the Historic Counties 1 Be County-Wise and get to know the Historic Counties abcounties.com/press-and-media [email protected] Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 2 About the Association of British Counties ....................................................................... 2 About County-Wise .............................................................................................................. 2 Top ten county facts ........................................................................................................... 6 Quick county quotes .......................................................................................................... 9 Where to find a county – quickly and easily ................................................................... 10 Frequently asked questions about the counties ............................................................... 11 First published in the United Kingdom in 2014 by the Association of British Counties. Copyright © The Association of British Counties 2014 County-Wise county-wise.org.uk A guide to the historic counties for the Press and Media 2 Introduction The identity of the historic counties has become confused by the use of the term -

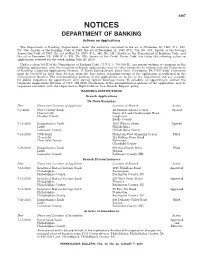

NOTICES DEPARTMENT of BANKING Actions on Applications

4397 NOTICES DEPARTMENT OF BANKING Actions on Applications The Department of Banking (Department), under the authority contained in the act of November 30, 1965 (P. L. 847, No. 356), known as the Banking Code of 1965; the act of December 14, 1967 (P. L. 746, No. 345), known as the Savings Association Code of 1967; the act of May 15, 1933 (P. L. 565, No. 111), known as the Department of Banking Code; and the act of December 19, 1990 (P. L. 834, No. 198), known as the Credit Union Code, has taken the following action on applications received for the week ending July 20, 2010. Under section 503.E of the Department of Banking Code (71 P. S. § 733-503.E), any person wishing to comment on the following applications, with the exception of branch applications, may file their comments in writing with the Department of Banking, Corporate Applications Division, 17 North Second Street, Suite 1300, Harrisburg, PA 17101-2290. Comments must be received no later than 30 days from the date notice regarding receipt of the application is published in the Pennsylvania Bulletin. The nonconfidential portions of the applications are on file at the Department and are available for public inspection, by appointment only, during regular business hours. To schedule an appointment, contact the Corporate Applications Division at (717) 783-2253. Photocopies of the nonconfidential portions of the applications may be requested consistent with the Department’s Right-to-Know Law Records Request policy. BANKING INSTITUTIONS Branch Applications De Novo Branches Date Name -

The Role and Effectiveness of Parish Councils in Gloucestershire

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Worcester Research and Publications The Role and Effectiveness of Parish Councils in Gloucestershire: Adapting to New Modes of Rural Community Governance Nicholas John Bennett Coventry University and University of Worcester April 2006 Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER TITLE PAGE NO. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 8 ABSTRACT 9 1 INTRODUCTION – Research Context, Research Aims, 11 Thesis Structure 2 LITERATURE REVIEW I: RURAL GOVERNANCE 17 Section 2.1: Definition & Chronology 17 Section 2.2 : Theories of Rural Governance 27 3 LITERATURE REVIEW II: RURAL GOVERNANCE 37 Section 3.1: The Role & Nature of Partnerships 37 Section 3.2 : Exploring the Rural White Paper 45 Section 3.3 : The Future Discourse for Rural Governance 58 Research 4 PARISH COUNCILS IN ENGLAND/INTRODUCTION TO 68 STUDY REGION 5 METHODOLOGY 93 6 COMPOSITION & VIBRANCY OF PARISH COUNCILS 106 IN GLOUCESTERSHIRE 7 ISSUES & PRIORITIES FOR PARISH COUNCILS 120 8 PARISH COUNCILS - ROLES, NEEDS & CONFLICTS 138 9 CONCLUSIONS 169 BIBLIOGRAPHY 190 ANNEXES 1 Copy of Parish Council Postal Questionnaire 200 2 Parish Council Clerk Interview Sheet & Observation Data 210 Capture Sheet 3 Listing of 262 Parish Councils in the administrative 214 county of Gloucestershire surveyed (Bolded parishes indicate those who responded to survey) 4 Sample population used for Pilot Exercise 217 5 Listing of 10 Selected Case Study Parish Councils for 218 further observation, parish clerk interviews & attendance at Parish Council Meetings 4 LIST OF MAPS, TABLES & FIGURES MAPS TITLE PAGE NO. -

The Drivers of Collaboration in Two-Tier Areas

The drivers of collaboration Working in partnership across local government Executive summary Delivering an effective response to changes in leadership can create the coronavirus means collaboration between conditions for closer joint working. Even in county and district councils is more areas where relationships are good, they important than ever. require continuing time and attention. This was the key message in an article in 2. Formal structures. Formal structures the Local Government Chronicle written by such as leaders’ groups, joint committees, the chairs of the County Councils’ Network growth boards, collaboration agreements (CCN) and District Councils’ Network (DCN) in and district deals are important in March 2020. Councillors John Fuller and David providing a robust framework for Williams wrote: “One thing is for sure: we stand collaboration and collective decision- the best possible chance of success and making. It is also important to create then recovery by working together during this the space and opportunities for informal period of national emergency.” meetings and real discussion. In this report, which was commissioned well 3. Joint posts and double hatting. Joint before the first outbreak of coronavirus, we posts and more extensive joint officer have set out the results of our research into arrangements deliver benefits for the the factors which drive collaboration between councils directly involved and wider district and county councils. district/county relationships. Members with roles in both types of council can Our evidence is drawn from a combination of also bring benefits to wider collaboration. attributable and non-attributable interviews in 12 areas with county and district councils. 4. -

Children and Young People's Committee Monday, 17 December 2018 at 10:30 County Hall, West Bridgford, Nottingham, NG2 7QP

Children and Young People's Committee Monday, 17 December 2018 at 10:30 County Hall, West Bridgford, Nottingham, NG2 7QP AGENDA 1 Minutes of the last meeting held on 19 November 2018 3 - 8 2 Apologies for Absence 3 Declarations of Interests by Members and Officers:- (see note below) (a) Disclosable Pecuniary Interests (b) Private Interests (pecuniary and non-pecuniary) 4 Annual Refresh of Local Transformation Plan for Children and 9 - 16 Young People's Emotional and Mental Health 5 Elective Home Education - Update 17 - 28 6 Update on Supporting Improvements in Children's Social Care 29 - 34 7 Proposed Changes to Staffing Structures Arising from the 35 - 38 Establishment of the Regional Adoiption Agency, Adoption East Midlands 8 Local Authority Governor Appointments to School Governing Bodies 39 - 42 During the Period 1 September to 31 December 2018 9 Promoting and Improving the Health of Looked After Children 43 - 72 10 Work Programme 73 - 78 Page 1 of 78 Notes (1) Councillors are advised to contact their Research Officer for details of any Group Meetings which are planned for this meeting. (2) Members of the public wishing to inspect "Background Papers" referred to in the reports on the agenda or Schedule 12A of the Local Government Act should contact:- Customer Services Centre 0300 500 80 80 (3) Persons making a declaration of interest should have regard to the Code of Conduct and the Council’s Procedure Rules. Those declaring must indicate the nature of their interest and the reasons for the declaration. Councillors or Officers requiring clarification on whether to make a declaration of interest are invited to contact Martin Gately (Tel. -

Weren't Many of the Historic Counties Altered Or Abolished by Local

Some frequently asked questions and answers regarding our counties. This selection is taken from information provided online by the Association of British Counties located at https://abcounties.com/questions/ Weren’t many of the historic Counties altered or abolished by local government reorganisations in the 1960s and 1970s? It is a commonly held misconception that the local government changes of the 1960s and 1970s actually altered the historic Counties of Britain. In fact they did no such thing. Modern local authority areas were only created in 1889 (in England and Wales) and 1890 (in Scotland). Initially these areas were closely based upon the historic Counties. However, they were always understood to be separate entities from the Counties themselves and, indeed, had separate terminology: they were labeled “administrative counties” and “county boroughs”. Nobody ever confused the local government areas with the historic Counties themselves. After all, the Counties of England had, by 1889, already been in existence for over 800 years (many for centuries longer). Those of Wales and Scotland had also been fixed in name and area for several centuries. The local government reorganisations of the 1960s and 1970s abolished all the “administrative counties” and “county boroughs” and created a whole new set of local government areas. However, it did not alter or abolish the Counties themselves. In Scotland the new top tier administrative areas were called “regions”. However, in England and Wales the new top tier local government areas were, confusingly, labelled “counties”. It is this use of the word “county” to mean something other than the real historic Counties which lies at the root of the confusion of the last 40 years. -

Cork County Age Friendly Town Fund 2020 Information

County Cork Age Friendly Town Fund Supporting the development of a network of Age Friendly Towns across County Cork 2020 - 2021 1 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Purpose and context This document sets out an initiative to support the development of a network of Age Friendly Towns across Cork during the lifetime of the Cork Age Friendly County Programme. This document sets out the proposal, its context and rationale, scope and benefits. The Age Friendly Ireland “Age Friendly Towns – a Guide” should be consulted for more detail. These forms are available through the Cork Age Friendly Office: Mary Creedon - Phone 021 4285557 Email [email protected] Or Noelle Desmond - Phone 021 4285161 Email [email protected] 2 BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT: AGE FRIENDLY TOWNS One of the most significant social changes facing countries around the world today is the ‘ageing population’ phenomenon. Globally we are witnessing a shift in the distribution of our population towards older ages. And Ireland is no different: According to the Central Statistics Office: • average life expectancy for men in Ireland is 76.8 years and 81.6 years for women • life expectancy at 65 is rising faster in Ireland than anywhere else in the EU • by 2041, there will be around 1.3-1.4m people in Ireland over the age of 65 – that’s one out of every four or five people • of these, 440,000 will be aged 80 or more – that’s four times as many as in 2006. The initiative proposed – developing a network of Age Friendly Towns in Cork – will complement and enhance the wider and now well established national Age Friendly Cities & Counties Programme which is currently operational in all 31 local authority areas across Ireland. -

Brief for Completion of Overview of Area Based Initiatives to Support Local Economic Development

Innovative approaches to participative community based socio-economic planning: Developing a model to underpin the sustainability of Ireland's local communities Commissioned by Ballyhoura Development Ltd and completed by Seán Ó'Riordáin & Associates October 2011 1 Table of Contents Pages Executive Summary 3-6 Introduction 7-9 The Case Studies on Community/Area-based Processes 10-22 Understanding Community Planning and its role in local economic 23-26 development including existing Arrangements in Ireland Lessons from the Case Studies 27-31 Application of the IAP/ADOPT/Communities Futures Planning Processes 32-33 Defining the geographic scope for community plans 34-36 Stimulation of the community and local elected representatives 37-39 Application to meet Minister's Objectives 40-42 Appendices Appendix 1: Community planning in the context of a move towards a municipal structure at sub-county level. 43-49 Appendix 2: From community socio-economic plans to municipal organisation 50-53 Appendix 3: Overview of ADOPT Model 54-57 Appendix 4: Actions undertaken in Mallow 58-59 Appendix 5: Interviewees 60-61 Figures Figure1: Community Planning Process 29-31 2 Executive Summary This report has been commissioned by Ballyhoura Development Ltd. to provide an overview of community/area based initiatives across Ireland. The report examines such initiatives in Counties Cork, Limerick, Mayo and Offaly. The research for the report is based on a desk top review of material made available for the research. A series of one to one interviews by telephone and a workshop of those interviewed were also conducted. The Report highlights a range of approaches to undertaking participative community based planning. -

Agenda Solent NHS Trust In-Public Board Meeting 27Th March 2017 10.30-13:05Pm Kestrel 1 & 2, Highpoint Venue, Bursledon Road, Southampton, SO19 8BR

Agenda Solent NHS Trust In-Public Board Meeting 27th March 2017 10.30-13:05pm Kestrel 1 & 2, Highpoint Venue, Bursledon Road, Southampton, SO19 8BR *Timings are tentative Item Time Dur. Title & Recommendation Exec Lead / Presenter 1 10:30 5mins Chairman’s Welcome & Update Chair • Apologies to receive To receive 2 Register of Interests & Declaration of Interests Chair To receive 3 Confirmation that meeting is Quorate Chair No business shall be transacted at meetings of the Board unless the following are present; • a minimum of two Executive Directors • at least two Non-Executive Directors including the Chair or a designated Non-Executive deputy Chair 4 *Minutes of Last Meeting and action tracker Chair To agree 5 10:35 5mins Matters Arising Chair 6 10:40 5mins Any Other Business Chair (not on the agenda but advised and agreed with the Chair for inclusion at this meeting) 7 10:45 15mins Safety and Quality First – including feedback from recent Chief Board to Floor Visits Executive / To receive Chief Nurse Strategy & Vision 8 11:00 10mins Chief Executive Report Chief To receive Executive 9 11:10 5mins Consideration of the Trust’s Foundation Trust application Chief Executive To agree / Director of Finance & Performance 10 11:15am 15mins Annual Staff Survey Feedback Director of To receive Finance & Performance Solent NHS Trust Headquarters, Highpoint Venue, Bursledon Rd, Southampton, SO19 8BR Telephone: 023 8060 8900 Fax: 023 8053 8740 Website: www.solent.nhs.uk Programme Delivery 11 11:30am 20mins Mental Health benchmarking Clinical Director -

NOTICES DEPARTMENT of BANKING Actions on Applications

3131 NOTICES DEPARTMENT OF BANKING Actions on Applications The Department of Banking (Department), under the authority contained in the act of November 30, 1965 (P. L. 847, No. 356), known as the Banking Code of 1965; the act of December 14, 1967 (P. L. 746, No. 345), known as the Savings Association Code of 1967; the act of May 15, 1933 (P. L. 565, No. 111), known as the Department of Banking Code; and the act of December 19, 1990 (P. L. 834, No. 198), known as the Credit Union Code, has taken the following action on applications received for the week ending May 25, 2010. Under section 503.E of the Department of Banking Code (71 P. S. § 733-503.E), any person wishing to comment on the following applications, with the exception of branch applications, may file their comments in writing with the Department of Banking, Corporate Applications Division, 17 North Second Street, Suite 1300, Harrisburg, PA 17101-2290. Comments must be received no later than 30 days from the date notice regarding receipt of the application is published in the Pennsylvania Bulletin. The nonconfidential portions of the applications are on file at the Department and are available for public inspection, by appointment only, during regular business hours. To schedule an appointment, contact the Corporate Applications Division at (717) 783-2253. Photocopies of the nonconfidential portions of the applications may be requested consistent with the Department’s Right-to-Know Law Records Request policy. BANKING INSTITUTIONS Conversions Date Name and Location of Applicant Action 5-20-2010 From: Adams County National Bank Filed Gettysburg Adams County To: ACNB Bank Gettysburg Adams County Application for approval to convert from a national banking association to a Pennsylvania state-chartered bank and trust company.