The Secrets of O-Sensei's Art Hidden in Plain Sight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texas Aikido Seminar with Mark Larson Sensei (Takuto 匠人) January 13 & 14, 2018

Texas Aikido Seminar with Mark Larson Sensei (Takuto 匠人) January 13 & 14, 2018 Texas Niwa Aiki Shuren is excited to host Mark Larson Sensei at his first Texas Aikido seminar! Please join us in a fun weekend of sharing Traditional Aikido. All styles and affiliations are welcome. Mark Larson Sensei (Takuto 匠人), 6th Dan Founder and Chief Instructor, Minnesota Aiki Shuren Dojo www.aikido-shuren-dojo.com Mark Sensei was Morihiro Saito’s last long term American Uchideshi and is dedicated to teaching and sharing Traditional Aikido. Saito Sensei entrusted Mark to continue the Iwama Takemusu Aikikai organization in order to preserve and protect the Iwama style Aikido as taught by the Founder and Saito Shihan. Takuto 匠人 – A leader who receives a tradition and “austerely trains, maintains, instructs, and selflessly shares it with great vigor and spirit in order to keep that particular tradition alive”. Seminar Schedule Seminar Fees Saturday, January 13, 2018 Saturday $ 60 Registration 9:00 a.m. – 10:00 a.m. Sunday $ 40 Keiko 10:00 a.m. – Noon Weekend $ 90 Lunch Break Noon – 2:30 p.m. Keiko 2:30 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. Please bring your own jo and ken Dinner Celebration 6:30 p.m. Seminar t-shirts available Sunday, January 14, 2018 Seminar Location Registration 9:00 a.m. – 9:30 a.m. Becerra Judo & Jiu-Jitsu Club Keiko 9:30 a.m. – Noon 3035 S. Shiloh Rd, #175 Garland, TX 75041 View the Flyer and Registration in events on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/niwaaikishuren/ Texas Niwa Aiki Shuren Dojo Dinner Celebration Saturday, Jan 13, 2018 @ 6:30 p.m. -

One Circle Hold Harmless Agreement

Schools of Aikido This is not a definitive list of Aikido schools/sensei, but a list of teachers who have had great impact on Aikido and who you will want to read about. You can google them. With the exception of Koichi Tohei Sensei, all teachers pictured here have passed on, but their school/style/tradition of Aikido has been continued by their students. All of these styles of Aikido are taught in the United States, as well as in many other countries throughout the world. Morihei Ueshiba Founder of Aikido Gozo Shioda Morihiro Saito Kisshomaru Ueshiba Koichi Tohei Yoshinkai/Yoshinkan Iwama Ryu Aikikai Ki Society Ueshiba Sensei (Ô-Sensei) … Founder of Aikido. Opened the school which has become known as the Aikikai in 1932. Ô-Sensei’s son, Kisshomaru Ueshiba Sensei, became kancho of the Aikikai upon Ô-Sensei’s death. Shioda Sensei was one of Ô-Sensei’s earliest students. Founded the Yoshinkai (or Yoshinkan) school in 1954. Saito Sensei was Head Instructor of Ô-Sensei’s school in the rural town of Iwama in Ibaraki Prefecture. Saito Sensei became kancho of Iwama Ryu upon Ô-Sensei’s death. Tohei Sensei was Chief Instructor of the Aikikai upon Ô-Sensei’s death. In 1974 Tohei Sensei left the Aikikai Shin-Shin Toitsu “Ki Society” and founded or Aikido. Rod Kobayashi Bill Sosa Kobayashi Sensei became the direct student of Tohei Sensei in 1961. Kobayashi Sensei was the Chief Lecturer Seidokan International Aikido of Ki Development and the Chief Instructor of Shin-Shin Toitsu Aikido for the Western USA Ki Society (under Association Koichi Tohei Sensei). -

TAKEJI TOMITA First Experiences with Aikido…

TAKEJI TOMITA From studying with O-Sensei to the creation of Aïki Shin Myo Den. Takeji Tomita is a very charismatic master of During a training course set up by the University, Aikido. As a concrete thinker and as a teacher of he discovers the sanctuary of Aikido and the Dojo Takemusu Aiki, he has done much to spread this of Iwama in Ibaragi-Gun. There, in Iwama, aspect of O'Sensei's legacy throughout Europe. Tomita Sensei meets the founder of Aikido, O’Sensei Morihei Ueshiba for the first time. In this article we will recount the course of this « Gentleman-warrior of modern Aikido », He is deeply impressed by the personality of the who throughout his life has been able to develop latter. He also gets acquainted with Morihiro his Aikido by strictly observing the principles of Saito, who was to become his master. the Budo. From 1962 on, after his first visit in Iwama, he decides to follow the teaching of O'Sensei and of his assistant, Morihiro Saito Sensei. In 1968, he becomes Morihiro Saito's Uchideshi and is rapidly adopted by the Master's family. Being an honorary member of the Saito household was difficult because of the severe physical training it implied and because of the gardening work and the medical assistance provided by the Saito family to O-Sensei. Tomita Sensei practiced for about 7 years at the Iwama Dojo. Those years were for him formative years dedicated to education and to discovering the way of Budo. Soke Takeji Tomita Photo ©Johan Westin 2005 First experiences with Aikido… A high-level expert engaged in a constant search and evolution of his Aikido and a reknowned specialist of Aikido weapons (Aiki Jo and Aiki Ken), Tomita Sensei was born on 3rd February 1942 in Hamamatsu, in the province of Shizuoka, on the Japanese island of Honshu. -

Takemusu Aikido Compendium. 1

TAKEMUSU AIKIDO COMPENDIUM TRADITIONALAIKIDO.EU TAKEMUSU AIKIDO COMPENDIUM. 1 Welcome to the dojo! You have also inadvertently just joined a world -wide fellowship of aikidoka’s practicing this art. One of the many gifts Aikido bestows is this wider network where you are welcome, both on and off the mat, in all parts of the world where Aikido is practiced. At first this practice looks confusing. TheJapanese terminology, the rolling, the techniques which all look similar but different at the same time, the unexpected problem of figuring out which side is right and left! But Aikido is actually quite simple (that doesn’t mean easy!) so this introductory guide is meant to give some orientation and hopefully help with the initially somewhat confusing period before one finds one’s bearings and starts to see the simplicity embedded within all the apparent complexity of Aikido practice. Contents: 1. Introduction 2. Morihiro Saito Sensei 2. Takemusu Aikido 3. Aikido as Budo 4. Etiquette 4. The Dojo 5. The practice - ukemi - ritualized technical practice (kata) and free style practice (jiyu waza) - weapon training. 6. The technical structure of Aikido 7. The core techniques. 8. Terminology for naming techniques in Japanese 9. The ranks and the grading syllabus. 9. Guidelines for training in the Dojo. 10. Appendix 1: glossary of japanese terms 13. Appendix 2: ken and jo basic suburi 14. Appendix 3: recommended resources Morihiro Saito Sensei 9th Dan. 2 The style or line of Aikido that is taught in this school is known as Takemusu Aikido and is a traditional form of Aikido that was passed on from O Sensei (Morihei Ueshiba, 1883 - 1969, the Founder of Aikido) to the late Morihiro Saito Sensei (1928 -2002). -

Spring 2012 Bucks County Aikido Journal Buckscountyaikido.Com•802 New Galena Rd., Doylestown PA 18901•(215) 249-8462

Ensō • Issue 10, Spring 2012 Bucks County Aikido Journal BucksCountyAikido.com•802 New Galena Rd., Doylestown PA 18901•(215) 249-8462 Ha by George Lyons You may love Aikido now but you are headed for a crisis. And when yours arrives you will probably quit. So there you go. The hard news is out and you can’t say I didn’t tell you so. You might say, “I’m ready… bring it on.” But here’s the thing; your crisis will be uniquely yours, tailor made and targeted right at your blind spot. Damn! If only you could learn this swim but refusing to give up. Add to feel that way. Suffering has many without any of that. It’s such a beau- this that instead of one boat there is forms and when it comes as confu- tiful art, so noble and high minded, a whole fleet, some insist on rowing sion its pretty unsettling. Check in wonderful ideas to hear and think alone, while others work together, with yourself and listen. Confusion about. Embody? Even better! lots of boats, lots of ropes, lots of should not be mistaken for being The traditional way of organizing swimming… chaos! off track. There’s a difference and around this practice is so orderly. When you reach the point in your knowing what it is, is so important Lining up in straight lines, the rit- training where you see more, when as to be the central issue of our lives. uals, the forms, can give the idea things are not as simple as they used Hanging onto a trailing rope, the there is a promised land where all to be, it’s natural to long for the days idea of letting go comes to mind. -

AWA Newsletter

AWA DEC - 2017 | ISSUE 16 AWA | PAGE 01 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Jeremy M.L. Hix, Nidan Dojo Cho-Greater Lansing Aikido; Lansing, MI USA Reflecting on this year, I am inspired by those closest to me. Their perseverance, mental, physical, and emotional fortitude, go well beyond anything short of super human. There are some battles that cannot be won. As in Aikido, there is no winner or loser, only Masakatsu Agatsu "true victory is victory over oneself." Such is the life of people with chronic pain and fatigue. Conditions such as Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS), Chronic Fatigue, Rheumatoid Arthritis, and Migraines (to name a few from a long list) are "Invisible" in the sense that they may not present outward physical manifestations of the associated symptoms. Furthermore, the individual living with the condition may also feel invisible in the sense of "self" as they are dismissed as faking their ailments. Often, this causes feelings of isolation, depression, anxiety, and withdrawal. I'm fortunate to have two people in my life that are very close to my heart, both battling with invisible health conditions. They are relentless in their perseverance, in their ability to overcome. They practice Aikido on crutches, in wheelchairs, and are eager to learn. They travel to Japan and explore the world. They never give up. They never acquiesce. Through understanding, compassion, empathy, and love, we can help make visible the beautiful person beneath the vale of these chronic conditions. I would like to dedicate this editorial to my better halves: Kristy, and her sister, Kayla. Thank you both for your perseverance in the face of adversity, and for giving me the privilege of being your friend along the way. -

INTERNATIONAL AIKIDO KOSHUKAI April 9–10 2016

INTERNATIONAL AIKIDO KOSHUKAI April 9–10 2016 Seminars with SHIHAN PAOLO CORALLINI and SHIHAN ULF EVENÅS are a longstanding tradition. This year, for the first time teaching in Sweden, we have the pleasure and honor to invite the legendSTANLEY PRANIN SENSEI. Pranin Sensei is an Aikido researcher, author, and the editor of Aikido Journal. Furthermore he is a long time student of Morihiro Saito Shihan and the publisher of Morihiro Saito Shihans book series in the 90’s. This guarantees an extra dimension to this seminar and an unique opportunity to meet these three legends teaching together. The last class on Saturday, Pranin Sensei will be givning a lecture on Aikido which will be a fantastic way to deepen your knowledge about Aikido. LOCATION Frölunda Judoklubb, Klubbvägen 8. V. Frölunda FEES 900 SEK (€ 90), for the whole seminar, including the lecture on Saturday. One day 500 SEK (€ 50), not including the lecture. Only lecture 200 SEK (€ 20). Payment before first training. PARTY 160 SEK (€ 20). Notify participation when you register. ENROLMENT [email protected] (deadline is April 2, 2016). Since we can only accept a limited number of participants, priority will be given to those that apply for both days ACCOMMODATION Gothenburg Aikido Club 50 SEK (€ 5) per night, or Frölunda Judoklubb 75 SEK (€ 10) per night. Bring sleeping bag. Ibis Hotel, www.ibishotel.se/goteborg-molndal/ OTHER Bring ken and jo. Participants traveling by airplane can borrow weapons. Selling of products or advertising is permitted by Gothenburg Aikido Club only. All participants must be fully insured. Photographing and filming during classes is forbidden without permission. -

T.K. Chiba - Remembering Morihiro SAITO Sensei

T.K. Chiba - Remembering Morihiro SAITO Sensei Thanks & Copyright This essay originally appeared in Biran, the Aikido Journal of Birankai/USAF-Western Region. © Birankai international - http://www.birankai.org/ Memorial The Aikido world suffered another huge loss with the death of Morihiro Saito Shi- han, who passed away on May 13, 2002. He was a long-time follower and one of the senior disciples of the founder Morihei Ueshiba, and served as the caretaker of the Aikido Shrine in Iwama, Ibaragi Prefecture, Japan. His distinguished influence can be seen either directly or indirectly in almost every part of the globe. As he often called his art “traditional Aikido,” his art unquestionably carried the weight of O-Sensei’s direct transmission in its essence as well as from the perspective of historical fact. I have been lucky enough to have had opportunities to learn the art from Saito Sensei’s teaching at the time I be- came an uchideshi at the Iwama dojo in the late 1950s, as well as at the times he was invited to teach at Hombu Dojo one Sunday a month in the early 1960s. I still can hear the sound of his footsteps approaching the dojo from his house at Iwama, which was not more than 50 meters away, in the early morning for the morning O-Sensei and his student Saito Sensei class. As the peculiar sound of the geta (wooden shoes) echoed through the frosty pine woods, I had to consciously wake myself up, think- ing, “Here he comes.” I had to be ready not only for training on the mat, but to make sure everything had been done exactly the way it should be. -

岩 間 神 信 合 Fernando Delgado Y

Magazine Dentou IWAMA RYU Aikidō 岩 間 神 信 Iwama Shinshin Aiki Shurenkai 合 The genesis of an Institution Irimi Nage Relevant aspects 氣 of a cinematographic technique Aikido In Times 道 Of Covid-19 The impact of the pandemic on the traditional practice The Katana Origins, typology and symbols of the Samurai soul Aikido From A Gender Perspective Interview with Mónica Ramírez The first woman to get a dan degree Issue 01 / August 2020 in Iwama ryu in Chile foto: KURILLA BUDOKAN 2019 Issue 01 / August 2020 Magazine Dentou IWAMA RYU Aikidō Hitohira Saito Sensei 06 Welcome message Here in Chile, we celebrate 07 our dojo anniversary! 08 Editorial Budo, an approach to the complexity of the concept Budo: the Japanese foundation 10 of martial arts By Juan Carlos Morales Budo and the practice of aikido. In the words of master Alessandro Titarelli 11 Cover photography: Kurilla Budokan By Rodrigo Troncoso The tradition in our practice 12 lives in Iwama with 42 Key concepts: Hitohira Saito sensei 42 Kamisama, kamidana and kamiza By Fernando Delgado By Jorge Ulloa Iwama Shinshin Aiki Shurenkai The female colonization of The genesis of an institution 44 traditional aikido in Chile The Founder’s aikido By Marcela Cabezas and Josefina Ibáñez 16 Alessandro Tittarelli, by Rodrigo Troncoso The successor aikido In The Times Of Covid-19 The pandemic impact on the 22 By Tristão da Cunha traditional practice The Big Bang of Iwama Message from Hitohira Saito sensei 28 Shin Shin Aiki Shurenkai 52 regarding COVID-19 Hitohira Saito, 2004. Translation by: Miki Nakajima Translation by: Aikido South Florida The Institutional mitosis The global pandemic debacle 30 Kenny Sembokuya Sensei. -

MORIHEI UESHIBA Y MORIHIRO SAITO -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

MORIHEI UESHIBA Y MORIHIRO SAITO por Stanley Pranin Traducido por Pedro J. Riego([email protected]) Morihiro Saito, en Rohnert Park, California, en Septiembre del 2000 El proceso diversificación técnica comenzó en el aikido hasta antes de la muerte de su fundador, Morihei Ueshiba. Entre las tendencias prevalecientes en el aikido de hoy está la propuesta suave enfatizando técnicas circulares o de ki no nagare del Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba del Aikikai Hombu Dojo, el tan llamado estilo duro de la escuela del Yoshinkan Aikido liderado por Gozo Shioda Sensei, el énfasis en el concepto del "ki" del Shinshin Toitsu Aikido como es expuesto por Koichi Tohei Sensei, el sistema ecléctico de Minoru Mochizuki Sensei del Yoseikan Aikido, y el sistema deportivo de aikido el cual incluye competición desarrollado por Kenji Tomiki Shihan. A estos debe ser añadido el curriculum técnico unificado formulado por el 9th dan Aikikai Shihan Morihiro Saito. El punto de vista de Saito Sensei recalcando la relación entre el taijutsu y bukiwaza (aiki ken y jo) se ha convertido de hecho en standard para varios practicantes de aikido alrededor del mundo. Esto ha sido mayormente al éxito de sus muchos libros de técnicas de aikido y extensos viajes al extranjero. Introducción al aikido Morihiro Saito era un muchacho de 18 años delgaducho, y nada impresionante cuando por primera vez se encontró con Morihei Ueshiba en la aburrida Iwama-mura en Julio de 1946. Era un poco después del final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial y la práctica de artes marciales estaba prohibida por el GHQ. El fundador se había "oficialmente" retirado en Iwama por varios años aunque en realidad él estaba comprometido en entrenamiento intensivo y meditación en estos alrededores retirados. -

Aikido History, Layout 1

Page 1 AIKIDO HISTOR Y IN JAPAN The year 1942 is often cited as the beginning of modern aikido. It was at that time that the DAI NIHON BUTOKUKAI, desiring to achieve a standardizaton in teaching methodology and no- menclature for modern Japanese martial arts, reached an agreement with the KOBUKAI repre- sentative Minoru HIRAI to call the jujutsu form developed by Morihei UESHIBA aikido. 20 years before, in 1922, Ueshiba had received the teaching license "kyoji-dairi" from Sokaku TAKEDA of DAITO RYU. He subsequently modified these techniques and combined them with his knowledge of other styles such as YAGYU SHINGAN RYU or TENJIN SHINYO RYU into what was first called AIKI BUDOand finally, with a strong emphasis on spiritual and ethical aspects, AIKIDO.Thus, in 1942 AIKIDO joined the ranks of judo, kendo, kyudo and other modern martial arts. When viewed in terms of the development of Morihei Ueshiba's art, 1942 does coinciden- tally represent a time of great transformation as the founder retired to IWAMA that year in the midst of World War II. It was there he made great efforts to hone his technical skills and attain a higher spiritual plane. The founder himself declared that it was during the Iwama years that he perfected his aikido. It is therefore not unreasonable to consider 1942 as the dividing line between aiki budo and aikido. In reality, little aikido was practiced at this time in Japan due to the depletion of the ranks of young men who had been mobilized for the war effort. Thus, alt- hough the birth of aikido can be thought of as having occurred in 1942, its real growth began well after the end of the war. -

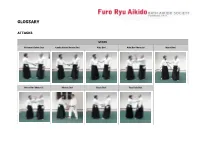

Aikido Glossary

GLOSSARY ATTACKS GRABS Ai Hanmi Katate Dori Gyaku Hanmi Katate Dori Kata Dori Kata Dori Menuchi Mune Dori Mune Dori Menuchi Morote Dori Ryote Dori Ryo Kata Dori STRIKES Shomen Uchi Yokomen Uchi Chudan Tsuki Jodan Tsuki Mae Geri GRABS FROM BEHIND (USHIRO WAZA) Ushiro Ryote Dori Ushiro Katate Dori Kubi Shime Ushiro Ryo Hiji Dori Ushiro Ryo Kata Dori Ushiro Katate Eri Dori TECHNIQUES/THROWS Ikkyo Nikyo Sankyo Yonkyo Gokyo First Principle/Teaching Second Principle/Teaching Third Principle/Teaching Fourth Principle/Teaching Fifth Principle/Teaching Rokkyo/Hiji Kime Oasae Irimi Nage Shiho Nage Kote Gaeshi Kokyu Nage Sixth Principle/Teaching Entering Throw Four Direction Throw Wrist Turn Breath Throw Kaiten Nage Koshi Nage Tenchi Nage Kokyu Ho/Sokumen Irimi Nage Ude Kime Nage Rotary Throw Hip Throw Heaven & Earth Throw Breath Principle Arm Lock Throw Sumi Otoshi Ushiro Kiri Otoshi Juji Nage Corner Drop Cutting Throw from Behind Cross Throw TERMINOLOGY Japanese English Ai Harmony/Blending/Unity/Love Ai Hanmi Mutual stance: both partners have same foot forward (opposite of Gyaku Hanmi) Aiki Blending or uniting with partner’s ki or spirit/energy Aikido The way of Aiki. Martial art founded by Morihei Ueshiba Aikidoka One who practices Aikido Aiki Jo Aikido Jo exercises. Term used by Morihiro Saito Sensei in the Iwama school Aikijutsu Literally: Art of Aiki. Term used to certain kinds of Jujutsu styles/schools pre-dating Aikido Aikikai The main Aikido organisation governing Aikido worldwide. Run from the Hombu dojo in Japan by the Ueshiba family Aiki Ken Aikido sword exercised. Term used by Morihiro Saito Sensei in the Iwama school Aiki Otoshi Aiki drop.