Cognitive Neuroscience of Ownership and Agency Q

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

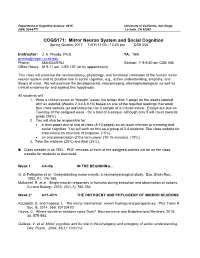

Mirror Neuron System and Social Cognition Spring Quarter 2017 Tuth 11:00 - 12:20 Pm CSB 005

Department of Cognitive Science 0515 University of California, San Diego (858) 534-6771 La Jolla, CA 92093 COGS171: Mirror Neuron System and Social Cognition Spring Quarter 2017 TuTH 11:00 - 12:20 pm CSB 005 Instructor: J. A. Pineda, Ph.D. TA: TBN [email protected] Phone: 858-534-9754 SeCtion: F 9-9:50 am CSB 005 OffiCe Hours: M 9-11 am, CSB 107 (or by appointment) This class will examine the neuroanatomy, physiology, and funCtional Correlates of the human mirror neuron system and its putative role in soCial Cognition, e.g., aCtion understanding, empathy, and theory of mind. We will examine the developmental, neuroimaging, electrophysiologiCal, as well as clinical evidence for and against this hypothesis. All students will: 1. Write a CritiCal review or “thought” essay (no longer than 1 page) on the weeks labeled with an asterisk (Weeks 2,3,4,6,8,10) based on one of the required readings that week. See Class website (or ask instruCtor) for a sample of a CritiCal review. Essays are due on Tuesday of the assigned week - for a total of 6 essays, although only 5 will count towards grade (25%). 2. You will also be responsible for: • a term paper due at end of class (8-10 pages) on an issue relevant to mirroring and social cognition. You will work on this as a group of 3-4 students. See Class website for instruCtions on structure of proposal. (15%) • an oral presentation of the term paper (10-15 minutes). (10%) 3. Take the midterm (25%) and final (25%). -

Phd Position on the Sensorimotor and Social Mechanisms of Hallucinations in Healthy Participants and Patients with Parkinson’S Disease

PhD position on the sensorimotor and social mechanisms of hallucinations in healthy participants and patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Prof. Olaf Blanke Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland The LaBoratory of Cognitive Neuroscience, directed By Olaf Blanke (https://www.epfl.ch/laBs/lnco/), has an open position for a PhD student on the investigation of the sensorimotor and social brain mechanisms of a specific hallucination (presence hallucination; Blanke et al., Current Biology 2014; Arzy et al., Nature 2006) in healthy participants and in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD). The project will couple roBotics, virtual reality (VR), experimental psychology, and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and is part of a larger research project on hallucinations. Most patients with PD are not only affected by motor symptoms (e.g., tremor), but also experience hallucinations as a symptom of the disease (Lenka et al., Neurology 2019). Despite the high prevalence of patients with hallucinations, the neural mechanisms remain poorly understood. By comBining MRI-compatible roBotics (Hara et al., J Neuroscience Methods 2014) and MRI-compatible VR, the present project plans to investigate how sensorimotor and social stimulation can induce and mimic symptomatic hallucinations (in patients with PD and in healthy participants) in a fully controlled environment. The ideal candidate should have a Master degree (or equivalent) in computer science, neuroscience, medicine, psychology, or engineering, Be strongly motivated with a keen interest in cognitive-systems neuroscience and neuroimaging/signal analysis. A strong neuroimaging background (fMRI), previous research experience in the experimental psychology, and/or strong programming skills (Matlab, python, etc.) are a plus. -

Empathy, Mirror Neurons and SYNC

Mind Soc (2016) 15:1–25 DOI 10.1007/s11299-014-0160-x Empathy, mirror neurons and SYNC Ryszard Praszkier Received: 5 March 2014 / Accepted: 25 November 2014 / Published online: 14 December 2014 Ó The Author(s) 2014. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract This article explains how people synchronize their thoughts through empathetic relationships and points out the elementary neuronal mechanisms orchestrating this process. The many dimensions of empathy are discussed, as is the manner by which empathy affects health and disorders. A case study of teaching children empathy, with positive results, is presented. Mirror neurons, the recently discovered mechanism underlying empathy, are characterized, followed by a theory of brain-to-brain coupling. This neuro-tuning, seen as a kind of synchronization (SYNC) between brains and between individuals, takes various forms, including frequency aspects of language use and the understanding that develops regardless of the difference in spoken tongues. Going beyond individual- to-individual empathy and SYNC, the article explores the phenomenon of syn- chronization in groups and points out how synchronization increases group cooperation and performance. Keywords Empathy Á Mirror neurons Á Synchronization Á Social SYNC Á Embodied simulation Á Neuro-synchronization 1 Introduction We sometimes feel as if we just resonate with something or someone, and this feeling seems far beyond mere intellectual cognition. It happens in various situations, for example while watching a movie or connecting with people or groups. What is the mechanism of this ‘‘resonance’’? Let’s take the example of watching and feeling a film, as movies can affect us deeply, far more than we might realize at the time. -

How Much Are We Willing to Pay for a Fossil?

OPINION NATURE|Vol 462|24/31 December 2009 CORRESPONDENCE Goodbye to Darwin popular religious beliefs in some ‘theory of progressive change’. (1858–1925) and Otto Dix conservative societies across the In fact, the word jinhualun (1891–1969). Some milder from a contemporary eastern world. There, the writings originated in Japan in the 1870s, conditions can even enhance with vision and thoughts of intellectuals, gaining popularity in China only productivity and creativity. For however influential, are no match after appearing in Ma Junwu’s example, the metaphysical art of One night some 40 years ago, for traditional religion. later translation of Darwin’s The Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978) I was working late and alone in the For example, in Pakistan it was Origin of Species. may have been inspired by library at the Marine Biology not until 2002 that a chapter on Instead, Yan Fu coined the migraine or epilepsy. Laboratory at Woods Hole (in evolution was included for the term tianyanlun. The Chinese Kemp focuses entirely those days, the library never really first time in a school textbook, as a words tian and yan are layered in on the beholder, as though closed), searching for something result of the federal government’s meaning, with tian translatable as — to paraphrase the French in the 1882 volume of Archiv für educational reforms. The earlier ‘heaven’ and yan as ‘development’ philosopher Roland Barthes Protistenkunde. As I opened it, out decades of attempts to suppress or ‘performance’, among other (Aspen 5–6; 1967) — the birth of fell a folded page from the magazine scientific ideas were certainly not concepts. -

3. Memory Enhancement and Cognitive Engineering

3. Memory enhancement and cognitive engineering By Olaf Blanke (Professor and Bertarelli Chair in Cognitive Neuroprosthetics, EPFL), Baptiste Gauthier (Senior Researcher, EPFL) with contributions through interviews from Itzhak Fried (Professor at the Brain Research Institute, University of California Los Angeles), Johannes Gräff (Professor at the Laboratory of Neuroepigenetics) , Bryan Johnson (CEO, Kernel) and Michael Kahana (Professor for Computational Memory, University of Pennsylvania) and edited by Moheb Costandi. Key Concepts Deep Brain Stimulation is an experimental surgical procedure that involves chronic implantation of stimulating wire electrodes into deep brain structures. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Deep Brain Stimulation as a treatment for the motor symptoms of movement disorders in 1997, and since then the technique has been used to treat approximately 150,000 Parkinson’s Disease patients. It is also being used experimentally to treat various psychiatric conditions, including major depressive disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Optogenetics is an experimental technique that offers by far the most sophisticated approach to manipulating memories. Developed over the past 15 years, optogenetics involves targeting specific neuronal cell types with genetic constructs containing light-sensitive algal genes. The constructs render specific, genetically targeted sub-sets of neurons sensitive to light, so that they can be activated or inhibited with light pulses delivered into the brain by means of optical fibres. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation stimulates brain activity by inducing a magnetic field that modulates the activity of neuronal populations within a targeted region of the cerebral cortex. Developed in 1985, the technique is being investigated as a treatment for various psychiatric conditions and received FDA approval as a treatment for drug-resistant major depression in 2008. -

1 the Development of Empathy: How, When, and Why Nicole M. Mcdonald & Daniel S. Messinger University of Miami Department Of

1 The Development of Empathy: How, When, and Why Nicole M. McDonald & Daniel S. Messinger University of Miami Department of Psychology 5665 Ponce de Leon Dr. Coral Gables, FL 33146, USA 2 Empathy is a potential psychological motivator for helping others in distress. Empathy can be defined as the ability to feel or imagine another person’s emotional experience. The ability to empathize is an important part of social and emotional development, affecting an individual’s behavior toward others and the quality of social relationships. In this chapter, we begin by describing the development of empathy in children as they move toward becoming empathic adults. We then discuss biological and environmental processes that facilitate the development of empathy. Next, we discuss important social outcomes associated with empathic ability. Finally, we describe atypical empathy development, exploring the disorders of autism and psychopathy in an attempt to learn about the consequences of not having an intact ability to empathize. Development of Empathy in Children Early theorists suggested that young children were too egocentric or otherwise not cognitively able to experience empathy (Freud 1958; Piaget 1965). However, a multitude of studies have provided evidence that very young children are, in fact, capable of displaying a variety of rather sophisticated empathy related behaviors (Zahn-Waxler et al. 1979; Zahn-Waxler et al. 1992a; Zahn-Waxler et al. 1992b). Measuring constructs such as empathy in very young children does involve special challenges because of their limited verbal expressiveness. Nevertheless, young children also present a special opportunity to measure constructs such as empathy behaviorally, with less interference from concepts such as social desirability or skepticism. -

Neural Mechanisms of Embodiment Asomatognosia Due to Premotor Cortex Damage

OBSERVATION Neural Mechanisms of Embodiment Asomatognosia Due to Premotor Cortex Damage Shahar Arzy, MD; Leila S. Overney, PhD; Theodor Landis, MD; Olaf Blanke, MD, PhD Background: Patients with asomatognosia generally de- and motor cortices. The patient’s pathological embodi- scribe parts of their body as missing or disappeared from cor- ment for her left arm was associated with mild left poreal awareness. This disturbance is generally attributed somatosensory loss, mild frontal dysfunction, and a to damage in the right posterior parietal cortex. However, behavioral deficit in the mental imagery of human recent neuroimaging and electrophysiological studies sug- arms. gest that corporeal awareness and embodiment of body parts areinsteadlinkedtothepremotorcortexofbothhemispheres. Conclusion: Asomatognosia may also be associated with damage to the right premotor cortex. Patient: We describe a patient with asomatognosia of her left arm due to damage in the right premotor Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1022-1025 SOMATOGNOSIA IS DEFINED arm or hand. After several minutes, the pa- as a patient’s feeling that tient experienced progressive restoration of parts of his or her body are her left hand and arm starting laterally, then “missing” or have disap- medially (Figure 1C), while leaving 2 holes peared from corporeal in the middle of her hand (Figure 1D). Later awareness.A1 Evidence from patients with fo- the 2 holes fused (Figure 1E) until the arm cal brain damage suggests that asomatog- was complete again (Figure 1F), and she was nosia is linked to posterior parietal le- able to move it some minutes later. No other sions, especially of the right hemisphere, bodypartsorelementsofextrapersonalspace and generally affects the contralesional were experienced as modified. -

CNS 2014 Program

Cognitive Neuroscience Society 21st Annual Meeting, April 5-8, 2014 Marriott Copley Place Hotel, Boston, Massachusetts 2014 Annual Meeting Program Contents 2014 Committees & Staff . 2 Schedule Overview . 3 . Keynotes . 5 2014 George A . Miller Awardee . 6. Distinguished Career Contributions Awardee . 7 . Young Investigator Awardees . 8 . General Information . 10 Exhibitors . 13 . Invited-Symposium Sessions . 14 Mini-Symposium Sessions . 18 Poster Schedule . 32. Poster Session A . 33 Poster Session B . 66 Poster Session C . 98 Poster Session D . 130 Poster Session E . 163 Poster Session F . 195 . Poster Session G . 227 Poster Topic Index . 259. Author Index . 261 . Boston Marriott Copley Place Floorplan . 272. A Supplement of the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience Cognitive Neuroscience Society c/o Center for the Mind and Brain 267 Cousteau Place, Davis, CA 95616 ISSN 1096-8857 © CNS www.cogneurosociety.org 2014 Committees & Staff Governing Board Mini-Symposium Committee Roberto Cabeza, Ph.D., Duke University David Badre, Ph.D., Brown University (Chair) Marta Kutas, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Adam Aron, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Helen Neville, Ph.D., University of Oregon Lila Davachi, Ph.D., New York University Daniel Schacter, Ph.D., Harvard University Elizabeth Kensinger, Ph.D., Boston College Michael S. Gazzaniga, Ph.D., University of California, Gina Kuperberg, Ph.D., Harvard University Santa Barbara (ex officio) Thad Polk, Ph.D., University of Michigan George R. Mangun, Ph.D., University of California, -

Visual Recognition of Words Learned with Gestures Induces Motor

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Visual recognition of words learned with gestures induces motor resonance in the forearm muscles Claudia Repetto1*, Brian Mathias2,3, Otto Weichselbaum4 & Manuela Macedonia4,5,6 According to theories of Embodied Cognition, memory for words is related to sensorimotor experiences collected during learning. At a neural level, words encoded with self-performed gestures are represented in distributed sensorimotor networks that resonate during word recognition. Here, we ask whether muscles involved in gesture execution also resonate during word recognition. Native German speakers encoded words by reading them (baseline condition) or by reading them in tandem with picture observation, gesture observation, or gesture observation and execution. Surface electromyogram (EMG) activity from both arms was recorded during the word recognition task and responses were detected using eye-tracking. The recognition of words encoded with self-performed gestures coincided with an increase in arm muscle EMG activity compared to the recognition of words learned under other conditions. This fnding suggests that sensorimotor networks resonate into the periphery and provides new evidence for a strongly embodied view of recognition memory. Traditional perspectives in cognitive science describe human behaviour as mediated by cognitive representations1. Such representations have been defned as mental structures that encode, store and process information arising from sensory-motor systems 2. According to these perspectives, information provided to perceptual systems about the environment is incomplete. As a result, the brain has the essential role of transforming this information into cognitive representations, which enable rapid and accurate behaviours. In recent years, embodied approaches have claimed that perception, action and the environment jointly contribute to cognitive processes3,4, highlighting a change in our understanding of the role of the body in cognition. -

Reading Action Word Affects the Visual Perception of Biological Motion Christel Bidet-Ildei, Laurent Sparrow, Yann Coello

Reading action word affects the visual perception of biological motion Christel Bidet-Ildei, Laurent Sparrow, Yann Coello To cite this version: Christel Bidet-Ildei, Laurent Sparrow, Yann Coello. Reading action word affects the visual perception of biological motion. Acta Psychologica, Elsevier, 2011, 137 (3), pp.330 - 334. 10.1016/j.actpsy.2011.04.001. hal-01773532 HAL Id: hal-01773532 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01773532 Submitted on 17 Sep 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Reading action word affects the visual perception of biological motion Christel Bidet-Ildei 1,2 , Laurent Sparrow 1, Yann Coello 1 1 URECA (EA 1059), University of Lille-Nord de France, 2 CeRCA, UMR-CNRS 6234, University of Poitiers. Corresponding author: Pr Yann Coello. Email: [email protected] Running title: Biological motion perception Keywords: Perception; Vision; Biological motion; Motor cognition, Language; Priming; Point-light display. Mailing Address: Pr. Yann COELLO URECA Université Charles De Gaulle – Lille3 BP 60149 59653 Villeneuve d'Ascq cedex, France Tel: +33.3.20.41.64.46 Fax: +33.3.20.41.60.32 Email: [email protected] 1 Abstract In the present study, we investigate whether reading an action-word can influence subsequent visual perception of biological motion. -

The Social-Emotional Processing Stream: Five Core Constructs and Their Translational Potential for Schizophrenia and Beyond Kevin N

The Social-Emotional Processing Stream: Five Core Constructs and Their Translational Potential for Schizophrenia and Beyond Kevin N. Ochsner Background: Cognitive neuroscience approaches to translational research have made great strides toward understanding basic mecha- nisms of dysfunction and their relation to cognitive deficits, such as thought disorder in schizophrenia. The recent emergence of Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience has paved the way for similar progress to be made in explaining the mechanisms underlying the social and emotional dysfunctions (i.e., negative symptoms) of schizophrenia and that characterize virtually all DSM Axis I and II disorders more broadly. Methods: This article aims to provide a roadmap for this work by distilling from the emerging literature on the neural bases of social and emotional abilities a set of key constructs that can be used to generate questions about the mechanisms of clinical dysfunction in general and schizophrenia in particular. Results: To achieve these aims, the first part of this article sketches a framework of five constructs that comprise a social-emotional processing stream. The second part considers how future basic research might flesh out this framework and translational work might relate it to schizophrenia and other clinical populations. Conclusions: Although the review suggests there is more basic research needed for each construct, two in particular—one involving the bottom-up recognition of social and emotional cues, the second involving the use of top-down processes to draw mental state inferences— are most ready for translational work. Key Words: Amygdala, cingulate cortex, cognitive neuroscience, and methods this new work employs, it can be difficult to figure emotion, prefrontal cortex, schizophrenia, social cognition, transla- out how diverse pieces of data fit together into core neurofunc- tional research tional constructs. -

MOTOR COGNITION Neurophysiological Underpinning of Planning and Predicting Upcoming Actions

MOTOR COGNITION Neurophysiological underpinning of planning and predicting upcoming actions CLAUDIA D. VARGAS Laboratório de Neurobiologia II Instituto de Biofísica Carlos Chagas Filho CAPES Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro LABORATÓRIO DE NEUROBIOLOGIA II/IBCCF Gustav Klimt ELIANE VOLCHAN JOAO GUEDES DA FRANCA CLAUDIA D. VARGAS EQUIPE DE CONTROLE MOTOR EDUARDO MARTINS GHISLAIN SAUNIER MAITE DE MELO RUSSO MARIA LUIZA RANGEL MARCO A. GARCIA PAULA ESTEVES SEBASTIAN HOFLE THIAGO LEMOS VAGNER SA JOSE MAGALHAES MAGNO CADENGUE COLABORADORES UNISUAM -ERIKA C. RODRIGUES, LAURA ALICE DE OLIVEIRA LABORATORIO DE NEUROANATOMIA CELULAR- CECILIA HEDIN PEREIRA LABORATORIO DE BIOMECANICA/EEFD -LUIS AURELIANO IMBIRIBA DEPTO DE FISIOTERAPIA/ HCUFF-ANA PAULA FONTANA LABORATORIO DE NEUROCIENCIA DO COMPORTAMENTO UFF-MIRTES G. P. FORTES SETOR DE FISIOTERAPIA/HFAG -SOLANGE CANAVARRO LABS- FERNANDA TOVAR MOLL INSTITUTO DE NEUROCIENCIAS DE NATAL/ SIDARTA RIBEIRO-DRAULIO DE ARAUJO NUMEC/USP- ANTONIO GALVES INSTITUT DES SCIENCES COGNITIVES-CNRS ANGELA SIRIGU & KAREN REILLY UNITE PLASTICITE ET MOTRICITE INSERM THIERRY POZZO VALERIA DELLA MAGGIORE-UBA, ARGENTINA THE MOTOR CONTROL GROUP INVESTIGATES 1. INTERACTIONS BETWEEN EMOTION AND ACTION 2. MENTAL SIMULATION OF ACTIONS (S STATES) 3. PREDICTION OF ACTIONS 4. PLASTICITY AFTER CENTRAL AND PERIPHERAL LESIONS THE MOTOR CONTROL GROUP INVESTIGATES 1. INTERACTIONS BETWEEN EMOTION AND ACTION 2. MENTAL SIMULATION OF ACTIONS (S STATES) 3. PREDICTION OF ACTIONS 4. PLASTICITY AFTER CENTRAL AND PERIPHERAL LESIONS MOVEMENTS