Ehrharta Calycina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improved Conservation Plant Materials Released by NRCS and Cooperators Through December 2014

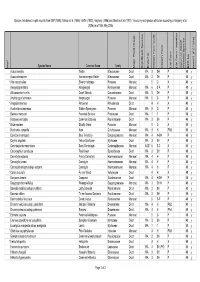

Natural Resources Conservation Service Improved Conservation Plant Materials Released by Plant Materials Program NRCS and Cooperators through December 2014 Page intentionally left blank. Natural Resources Conservation Service Plant Materials Program Improved Conservation Plant Materials Released by NRCS and Cooperators Through December 2014 Norman A. Berg Plant Materials Center 8791 Beaver Dam Road Building 509, BARC-East Beltsville, Maryland 20705 U.S.A. Phone: (301) 504-8175 prepared by: Julie A. DePue Data Manager/Secretary [email protected] John M. Englert Plant Materials Program Leader [email protected] January 2015 Visit our Website: http://Plant-Materials.nrcs.usda.gov TABLE OF CONTENTS Topics Page Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Types of Plant Materials Releases ........................................................................................................................2 Sources of Plant Materials ....................................................................................................................................3 NRCS Conservation Plants Released in 2013 and 2014 .......................................................................................4 Complete Listing of Conservation Plants Released through December 2014 ......................................................6 Grasses ......................................................................................................................................................8 -

Ehrharta Calycina

Information on measures and related costs in relation to species considered for inclusion on the Union list: Ehrharta calycina This note has been drafted by IUCN within the framework of the contract No 07.0202/2017/763436/SER/ENV.D2 “Technical and Scientific support in relation to the Implementation of Regulation 1143/2014 on Invasive Alien Species”. The information and views set out in this note do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Commission, or IUCN. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this note. Neither the Commission nor IUCN or any person acting on the Commission’s behalf, including any authors or contributors of the notes themselves, may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. This document shall be cited as: Visser, V. 2018. Information on measures and related costs in relation to species considered for inclusion on the Union list: Ehrharta calycina. Technical note prepared by IUCN for the European Commission. Date of completion: 25/10/2018 Comments which could support improvement of this document are welcome. Please send your comments by e-mail to [email protected]. Species (scientific name) Ehrharta calycina Sm. Pl. Ic. Ined. t. 33. Species (common name) Perennial veldt grass, purple veldt grass, veldt grass, common ehrharta, gewone ehrharta (Afrikaans), rooisaadgras (Afrikaans). Author(s) Vernon Visser, African Climate & Development Institute Date Completed 25/10/2018 Reviewer Courtenay A. Ray, Arizona State University Summary Highlight of measures that provide the most cost-effective options to prevent the introduction, achieve early detection, rapidly eradicate and manage the species, including significant gaps in information or knowledge to identify cost-effective measures. -

Montaña De Oro Checklist-07Jun19

Checklist1 of Vascular Flora of Montaña de Oro State Park San Luis Obispo County, California (07 June 2019) David J. Keil Robert F. Hoover Herbarium Biological Sciences Department California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n Abronia latifolia yellow sand-verbena NYCTAGINACEAE v n Abronia maritima beach sand-verbena, red NYCTAGINACEAE 4.2 v sand-verbena n Abronia umbellata var. umbellata purple sand-verbena NYCTAGINACEAE v n Acer macrophyllum big-leaf maple SAPINDACEAE v n ❀ Achillea millefolium yarrow ASTERACEAE v n Acmispon brachycarpus shortpod deervetch FABACEAE v 1 Please notify the author of additions or corrections to this list ([email protected]). ❀ — See Wildflowers of San Luis Obispo, California, second edition (2018) for photograph. Most are illustrated in the first edition as well; old names for some species in square brackets. n — California native n1 — California native but planted at Montaña de Oro. i — exotic species, introduced to California, naturalized or waif. v — documented by one or more specimens (Consortium of California Herbaria record; specimen in OBI; or collection that has not yet been accessioned) o — observed during field surveys; no voucher specimen known R—California Rare Plant Rank Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n ❀ Acmispon glaber var. glaber common deerweed FABACEAE v n Acmispon heermannii var. orbicularis woolly deer-vetch FABACEAE v n Acmispon junceus var. biolettii Biolett's rush deerweed FABACEAE v n Acmispon junceus var. junceus common rush deerweed FABACEAE v n Acmispon maritimus var. maritimus coastal deer-vetch FABACEAE v n Acmispon micranthus fishhook deervetch FABACEAE v n Acmispon parviflorus miniature deervetch FABACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon strigosus strigose deer-vetch FABACEAE v n Actaea rubra baneberry RANUNCULACEAE v n ❀ Adelinia grandis Pacific hound's tongue BORAGINACEAE v n ❀ Adenostoma fasciculatum var. -

BFS048 Site Species List

Species lists based on plot records from DEP (1996), Gibson et al. (1994), Griffin (1993), Keighery (1996) and Weston et al. (1992). Taxonomy and species attributes according to Keighery et al. (2006) as of 16th May 2005. Species Name Common Name Family Major Plant Group Significant Species Endemic Growth Form Code Growth Form Life Form Life Form - aquatics Common SSCP Wetland Species BFS No kens01 (FCT23a) Wd? Acacia sessilis Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Acacia stenoptera Narrow-winged Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Aira caryophyllea Silvery Hairgrass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Alexgeorgea nitens Alexgeorgea Restionaceae Monocot WA 6 S-R P 48 y Allocasuarina humilis Dwarf Sheoak Casuarinaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Amphipogon turbinatus Amphipogon Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y * Anagallis arvensis Pimpernel Primulaceae Dicot 4 H A 48 y Austrostipa compressa Golden Speargrass Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y Banksia menziesii Firewood Banksia Proteaceae Dicot WA 1 T P 48 y Bossiaea eriocarpa Common Bossiaea Papilionaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Briza maxima Blowfly Grass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Burchardia congesta Kara Colchicaceae Monocot WA 4 H PAB 48 y Calectasia narragara Blue Tinsel Lily Dasypogonaceae Monocot WA 4 H-SH P 48 y Calytrix angulata Yellow Starflower Myrtaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Centrolepis drummondiana Sand Centrolepis Centrolepidaceae Monocot AUST 6 S-C A 48 y Conostephium pendulum Pearlflower Epacridaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Conostylis aculeata Prickly Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis juncea Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis setigera subsp. -

Phylogeny and Subfamilial Classification of the Grasses (Poaceae) Author(S): Grass Phylogeny Working Group, Nigel P

Phylogeny and Subfamilial Classification of the Grasses (Poaceae) Author(s): Grass Phylogeny Working Group, Nigel P. Barker, Lynn G. Clark, Jerrold I. Davis, Melvin R. Duvall, Gerald F. Guala, Catherine Hsiao, Elizabeth A. Kellogg, H. Peter Linder Source: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, Vol. 88, No. 3 (Summer, 2001), pp. 373-457 Published by: Missouri Botanical Garden Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3298585 Accessed: 06/10/2008 11:05 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mobot. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. -

Flerårig Steppegræs (Ehrharta Calycina)

Flerårig steppegræs (Ehrharta calycina) Beskrivelse Videnskabeligt navn: Ehrharta calycina Sm. Synonymer: De hyppigst anvendte synonymer er Aira capensis L.f. Ehrharta ascendens Schrad. Ehrharta auriculata Steud. Ehrharta geniculate (Thunb.) Thunb. Melica festucoides Licht. Ex Trin. Trochera calycina Sm. P. Beauv. Kaldenavn: flerårig steppegræs Beskrivelse Flerårig steppegræs er en tuedannende 30-75 cm høj, som det danske navn siger, flerårig græs med grønne til grønviolette 2-7 mm brede blade1,2. Hver tue har typisk mange skud. Blomsterstanden er en åben 10-15 cm lang top med mange siddende eller kortstilkede småaks, der er 5-8 mm lange. I hvert småaks er der tre blomster, hvoraf kun den øverste er fertil. Yderavnerne er af længde som småakset og violette. Planten har en meget lang blomstringsperiode, der varer op til et halvt år2. Flerårig steppegræs er vindbestøvet og producerer mange frø, der naturligt primært spredes via vinden, men planten har også dyrespredning og spredes med vand. Frøene ligger sædvanligvis på jordoverfladen, hvor de spirer efter regn. Arten har dog også en frøbank, der kan opnå meget høje tætheder (75.000 frø pr. m2)2,3. Efter brand spirer sædvanligvis kun omkring halvdelen af frøbanken, således er der en reserve til senere måske mere gunstige tidpunkter for spiring og etablering3. Planten danner sjældent udløbere1. Vegetativ spredning ses hyppigst, hvor arten vokser i fugtige habitater2. Ved stængelbasis har planten hvileknopper, der skyder efter forstyrrelser2. Dette er især væsentligt i områder, hvor der forekommer brand; da frøene ligger på jordoverfladen er de meget udsatte ved brand hvorimod tuerne bedre tåler branden og spiring fra hvileknopperne fremmes ved brand3. -

Branch Circus Flora and Fauna Survey PDF Document

FLORA AND VEGETATION SURVEY Branch Circus and Hammond Road, Success Prepared by: Prepared for: RPS MUNTOC PTY LTD AND 290 Churchill Avenue, SUBIACO WA 6008 SILVERSTONE ASSET PTY LTD PO Box 465, SUBIACO WA 6904 C/O Koltasz Smith T: 618 9382 4744 PO Box 127 F: 618 9382 1177 E: [email protected] BURSWOOD WA 6100 W: www.rpsgroup.com.au Report No: L07263 Version/Date: Rev 0, June 2008 RPS Environment Pty Ltd (ABN 45 108 680 977) Document Set ID: 5546761 Version: 1, Version Date: 31/01/2017 Flora and Vegetation Survey Branch Circus and Hammond Road, Success Document Status Review Format RPS Release Issue Version Purpose of Document Orig Review Date Review Approval Date Draft A Draft For Internal Review KelMcC VanYeo 30.04.08 Draft B Draft For Client Review VanYeo KarGod 14.05.08 SN 30.05.08 Rev 0 Final for Issue VanYeo 10.06.08 DC 12.06.08 B. Hollyock 13.06.08 Disclaimer This document is and shall remain the property of RPS. The document may only be used for the purposes for which it was commissioned and in accordance with the Terms of Engagement for the commission. Unauthorised copying or use of this document in any form whatsoever is prohibited. L07263, Rev 0, June 2008 DOCUMENT STATUS / DISCLAIMER Document Set ID: 5546761 Version: 1, Version Date: 31/01/2017 Flora and Vegetation Survey Branch Circus and Hammond Road, Success EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Flora A total of 229 taxa were recorded from the survey area, of which 155 or 68% were native. -

Morro Creek Natural Environment Study

Morro Creek Multi-Use Trail and Bridge Project Natural Environment Study San Luis Obispo County, California Federal Project Number CASB12RP-5391(013) MB-2013-S2 05-SLO-0-MOBY December 2013 For individuals with sensory disabilities, this document is available in Braille, large print, on audiocassette, or computer disk. To obtain a copy in one of these alternate formats, please call or write to Caltrans, Attn: Brandy Rider, Caltrans District 5 Environmental Stewardship Branch, 50 Higuera Street, San Luis Obispo, CA 93401; 805-549-3182 Voice, or use the California Relay Service TTY number, 805-549-3259. This page is intentionally left blank. Summary Summary The City of Morro Bay is extending the existing Harborwalk with continuation of a paved pedestrian boardwalk and separate Class I bike path from the existing parking area and crossing on Embarcadero Avenue northward. The City also proposes to install a clear-span pre-engineered/pre-fabricated bike and pedestrian bridge over Morro Creek to connect to north Morro Bay on Embarcadero Road/State Route 41. In addition, the project will include improvements to beach access from the trail, and two interpretive sign stations that will display educational and other information about the cultural and natural history of the region. This project is receiving funding from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and with assistance from Caltrans. As part of its NEPA assignment of federal responsibilities by the FHWA, effective October 1, 2012 and pursuant to 23 USC 326, Caltrans is acting as the lead federal agency for Section 7 of the federal Endangered Species Act. -

Invasive Plant Patrol in Orange County

Invasive Plant Patrol: More Effective Early Detection and Rapid Response Through Community Engagement Adam Verrell, Josie Bennett, Alan Kaufmann Laguna Canyon Foundation Who Are We? Invasive Plant Patrol Survey Specifics Laguna Canyon Foundation is dedicated to preserving, protecting, enhancing, and • Surveys are conducted on a monthly basis on one of four trails prioritized for promoting the South Coast Wilderness – a network of nearly 30 square miles of likeliness of emergent introduction (see Sections 1-4 on map). contiguous open space that includes Laguna Coast Wilderness Park and Aliso and • Surveys are confined to approximately six feet on either side of the trail. Wood Canyons Wilderness Park in Orange County, CA. Our team is currently working • LCF staff lead surveys to assist in plant identification, herbicide application, and on over a dozen projects, including large-scale restoration, rare plant management, and entering and managing Calflora observations. fuel modification projects covering nearly 200 acres of habitat. In addition, Laguna • Observations are uploaded to the ‘OC Parks Weed Managers’ group on Calflora. Canyon Foundation advocates for environmentally responsible development, and When a weed is treated, treatment information is entered by creating a new fosters connections between people and the land though our education and record on the existing observation. stewardship programs. • While emergent weeds are top priority, all high priority invasive plants are recorded and mapped. • Trained volunteers are encouraged to upload observations and stay on the Invasive Plant Patrol is on the Job! lookout for emergent species any time they are in the Parks. • Invasive species pose one of the greatest global risks to biodiversity; therefore, catching native, invasive plants in the emergent phase is essential to effective land management. -

Grasses of Namibia Contact

Checklist of grasses in Namibia Esmerialda S. Klaassen & Patricia Craven For any enquiries about the grasses of Namibia contact: National Botanical Research Institute Private Bag 13184 Windhoek Namibia Tel. (264) 61 202 2023 Fax: (264) 61 258153 E-mail: [email protected] Guidelines for using the checklist Cymbopogon excavatus (Hochst.) Stapf ex Burtt Davy N 9900720 Synonyms: Andropogon excavatus Hochst. 47 Common names: Breëblaarterpentyngras A; Broad-leaved turpentine grass E; Breitblättriges Pfeffergras G; dukwa, heng’ge, kamakama (-si) J Life form: perennial Abundance: uncommon to locally common Habitat: various Distribution: southern Africa Notes: said to smell of turpentine hence common name E2 Uses: used as a thatching grass E3 Cited specimen: Giess 3152 Reference: 37; 47 Botanical Name: The grasses are arranged in alphabetical or- Rukwangali R der according to the currently accepted botanical names. This Shishambyu Sh publication updates the list in Craven (1999). Silozi L Thimbukushu T Status: The following icons indicate the present known status of the grass in Namibia: Life form: This indicates if the plant is generally an annual or G Endemic—occurs only within the political boundaries of perennial and in certain cases whether the plant occurs in water Namibia. as a hydrophyte. = Near endemic—occurs in Namibia and immediate sur- rounding areas in neighbouring countries. Abundance: The frequency of occurrence according to her- N Endemic to southern Africa—occurs more widely within barium holdings of specimens at WIND and PRE is indicated political boundaries of southern Africa. here. 7 Naturalised—not indigenous, but growing naturally. < Cultivated. Habitat: The general environment in which the grasses are % Escapee—a grass that is not indigenous to Namibia and found, is indicated here according to Namibian records. -

Unassisted Invasions: Understanding and Responding to Australia's High

CSIRO PUBLISHING Australian Journal of Botany, 2017, 65, 678–690 Turner Review No. 21 https://doi.org/10.1071/BT17152 Unassisted invasions: understanding and responding to Australia’s high-impact environmental grass weeds Rieks D. van Klinken A,C and Margaret H. Friedel B ACSIRO, EcoSciences Precinct, PO Box 2583, Brisbane, Qld 4001, Australia. BCSIRO, PO Box 2114, Alice Springs, NT 0871, Australia. CCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Alien grass species have been intentionally introduced into Australia since European settlement over 200 years ago, with many subsequently becoming weeds of natural environments. We have identified the subset of these weeds that have invaded and become dominant in environmentally important areas in the absence of modern anthropogenic disturbance, calling them ‘high-impact species’. We also examined why these high-impact species were successful, and what that might mean for management. Seventeen high-impact species were identified through literature review and expert advice; all had arrived by 1945, and all except one were imported intentionally, 16 of the 17 were perennial and four of the 17 were aquatic. They had become dominant in diverse habitats and climates, although some environments still remain largely uninvaded despite apparently ample opportunities. Why these species succeeded remains largely untested, but evidence suggests a combination of ecological novelty (both intended at time of introduction and unanticipated), propagule pressure (through high reproductive rate and dominance in nearby anthropogenically-disturbed habitats) and an ability to respond to, and even alter, natural disturbance regimes (especially fire and inundation). Serious knowledge gaps remain for these species, but indications are that resources could be better focused on understanding and managing this limited group of high-impact species. -

The Effect of Fire and Grazing on the Cumberland Plain Woodlands Samantha Clarke University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2004 The effect of fire and grazing on the Cumberland Plain Woodlands Samantha Clarke University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Clarke, Samantha, The effect of fire and grazing on the Cumberland Plain Woodlands, Master of Science - Research thesis, School of Biological Sciences, University of Wollongong, 2004. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2700 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The Effect of Fire and Grazing on the Cumberland Plain Woodlands A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Science (Research) from THE UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG By SAMANTHA CLARKE Bachelor of Science (Biology) DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES 2004 CERTIFICATION I, Samantha Clarke, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Master of Science (Research), in the Department of Biological Sciences, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Samantha Clarke 20 June 2004 ABSTRACT Temperate grassy woodlands throughout the world have suffered the effects of changed disturbance regimes, in particular, fire and grazing, due to human activities. Since European settlement fire and tree clearing has been used to modify grassy woodland vegetation for livestock grazing and agriculture. As a consequence some species, particularly shrubs and trees, have been reduced or eliminated and both native and introduced grasses have become more dominant.