Changing the Culture of Safety in the Fire Service by RONALD J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

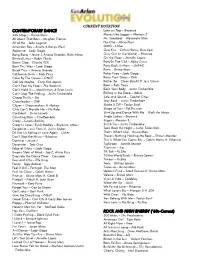

Front of House Master Song List

CURRENT ROTATION CONTEMPORARY DANCE Love on Top – Beyoncé 24K Magic – Bruno Mars Moves Like Jagger – Maroon 5 All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor Mr. Saxobeat – Alexandra Stan All of Me – John Legend No One – Alicia Keys American Boy – Estelle & Kanye West OMG – Usher Applause – Lady Gaga One Kiss – Calvin Harris, Dua Lipa Bang Bang – Jessie J, Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj Only Girl (in the World) – Rihanna Blurred Lines – Robin Thicke On the Floor – Jennifer Lopez Boom Clap – Charlie XCX Party In The USA – Miley Cyrus Born This Way – Lady Gaga Party Rock Anthem – LMFAO Break Free – Ariana Grande Perm – Bruno Mars California Gurls – Katy Perry Poker Face – Lady Gaga Cake By The Ocean – DNCE Raise Your Glass – Pink Call Me Maybe – Carly Rae Jepsen Rather Be – Clean Bandit ft. Jess Glynn Can’t Feel My Face – The Weeknd Roar – Katy Perry Can’t Hold Us – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Rock Your Body – Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling – Justin Timberlake Rolling in the Deep – Adele Cheap Thrills – Sia Safe and Sound – Capital Cities Cheerleader – OMI Sexy Back – Justin Timberlake Closer – Chainsmokers ft. Halsey Shake It Off – Taylor Swift Club Can’t Handle Me – Flo Rida Shape of You – Ed Sheeran Confident – Demi Lovato Shut Up and Dance With Me – Walk the Moon Counting Stars – OneRepublic Single Ladies – Beyoncé Crazy – Gnarls Barkley Sugar – Maroon 5 Crazy In Love / Funk Medley – Beyoncé, others Suit & Tie – Justin Timberlake Despacito – Luis Fonsi ft. Justin Bieber Take Back the Night – Justin Timberlake DJ Got Us Falling in Love Again – Usher That’s What I Like – Bruno Mars Don’t Stop the Music – Rihanna There’s Nothing Holding Me Back – Shawn Mendez Domino – Jessie J This Is What You Came For – Calvin Harris ft. -

Bad Habit Song List

BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song 4 Non Blondes Whats Up Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know Alanis Morissette Crazy Alanis Morissette You Learn Alanis Morissette Uninvited Alanis Morissette Thank You Alanis Morissette Ironic Alanis Morissette Hand In My Pocket Alice Merton No Roots Billie Eilish Bad Guy Bobby Brown My Prerogative Britney Spears Baby One More Time Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bruno Mars 24K Magic Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey Christina Aguilera Fighter Corey Hart Sunglasses at Night Cyndi Lauper Time After Time David Guetta Titanium Deee-Lite Groove Is In The Heart Dishwalla Counting Blue Cars DNCE Cake By the Ocean Dua Lipa One Kiss Dua Lipa New Rules Dua Lipa Break My Heart Ed Sheeran Blow BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song Elle King Ex’s & Oh’s En Vogue Free Your Mind Eurythmics Sweet Dreams Fall Out Boy Beat It George Michael Faith Guns N’ Roses Sweet Child O’ Mine Hailee Steinfeld Starving Halsey Graveyard Imagine Dragons Whatever It Takes Janet Jackson Rhythm Nation Jessie J Price Tag Jet Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jewel Who Will Save Your Soul Jo Dee Messina Heads Carolina, Tails California Jonas Brothers Sucker Journey Separate Ways Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Say Something Katy Perry Teenage Dream Katy Perry Dark Horse Katy Perry I Kissed a Girl Kings Of Leon Sex On Fire Lady Gaga Born This Way Lady Gaga Bad Romance Lady Gaga Just Dance Lady Gaga Poker Face Lady Gaga Yoü and I Lady Gaga Telephone BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song Lady Gaga Shallow Letters to Cleo Here and Now Lizzo Truth Hurts Lorde Royals Madonna Vogue Madonna Into The Groove Madonna Holiday Madonna Border Line Madonna Lucky Star Madonna Ray of Light Meghan Trainor All About That Bass Michael Jackson Dirty Diana Michael Jackson Billie Jean Michael Jackson Human Nature Michael Jackson Black Or White Michael Jackson Bad Michael Jackson Wanna Be Startin’ Something Michael Jackson P.Y.T. -

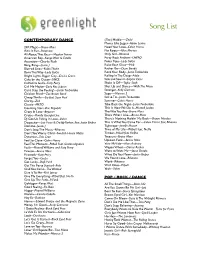

Greenlight's Complete Song List

Song List CONTEMPORARY DANCE (The) Middle—-Zedd Moves Like Jagger--Adam Levine 24K Magic—Bruno Mars Need Your Love--Calvin Harris Ain’t It Fun--Paramore No Roots—Alice Merton All About That Bass—Meghan Trainor Only Girl--Rihanna American Boy--Kanye West & Estelle Party Rock Anthem--LMFAO Attention—Charlie Puth Poker Face--Lady GaGa Bang, Bang—Jessie J Raise Your Glass—Pink Blurred Lines--Robin Thicke Rather Be—Clean Bandit Born This Way--Lady GaGa Rock Your Body--Justin Timberlake Bright Lights, Bigger City--Cee-Lo Green Rolling In The Deep--Adele Cake by the Ocean--DNCE Safe and Sound--Capitol Cities California Gurls--Katy Perry Shake It Off—Taylor Swift Call Me Maybe--Carly Rae Jepson Shut Up and Dance—Walk The Moon Can’t Stop the Feeling!—Justin Timberlake Stronger--Kelly Clarkson Chicken Fried—Zac Brown Band Sugar—Maroon 5 Cheap Thrills—Sia feat. Sean Paul Suit & Tie--Justin Timberlake Clarity--Zed Summer--Calvin Harris Classic--MKTO Take Back the Night--Justin Timberlake Counting Stars-One Republic This Is How We Do It--Montell Jordan Crazy In Love--Beyonce The Way You Are--Bruno Mars Cruise--Florida Georgia Line That’s What I Like—Bruno Mars DJ Got Us Falling In Love--Usher There’s Nothing Holdin’ Me Back—Shawn Mendes Despacito—Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee, feat. Justin Bieber This Is What You Came For—Calvin Harris feat. Rihanna Domino--Jessie J Tightrope--Janelle Monae Don’t Stop The Music--Rihanna Time of My Life—Pitbull feat. NeYo Don’t You Worry Child--Swedish House Mafia Timber--Pitbull feat. -

(OAS) and the Conference of Radiation Control Program Directors

1 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION + + + + + MEETING WITH THE ORGANIZATION OF AGREEMENT STATES (OAS) AND THE CONFERENCE OF RADIATION CONTROL PROGRAM DIRECTORS (CRCPD) + + + + + TUESDAY, APRIL 19, 2016 + + + + + ROCKVILLE, MARYLAND + + + + + The Commission met in the Commissioners’ Hearing Room at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, One White Flint North, 11555 Rockville Pike, at 9:30 a.m., Stephen G. Burns, Chairman, presiding. COMMISSION MEMBERS: STEPHEN G. BURNS, Chairman KRISTINE L. SVINICKI, Commissioner WILLIAM C. OSTENDORFF, Commissioner JEFF BARAN, Commissioner ALSO PRESENT: ROCHELLE BAVOL, Executive Assistant, Office of the Secretary of the Commission 2 MARGARET DOANE, General Counsel PARTICIPANTS: SHERRIE FLAHERTY, MHP, DC, Supervisor, Radioactive Materials Unity, Minnesota Department of Health (OAS Chair) WILLIAM IRWIN, SC.D., CHP, Program Chief, Radiological and Toxicological Sciences Program, Vermont Department of Health (CRCPD Chair) MATT MCKINLEY, Administrator, Radiation Health Branch, Kentucky Department for Public Health (OAS Chair- Elect) JARED THOMPSON, Program Manager, Radioactive Materials Program, Arkansas Department of Health (CRCPD Chair-Elect) MIKE WELLING, Director, Radioactive Materials Program, Virginia Department of Health (OAS Past Chair) 3 1 P R O C E E D I N G S 2 9:31 a.m. 3 CHAIRMAN BURNS: Okay. All right. Well, good 4 morning, everyone, and we want to welcome our representatives from 5 the Organization of Agreement States and the Conference of Radiation 6 Control Program Directors. -

Q&A REPORTING, INC. [email protected] Page 1

DISCLAIMER: This is NOT a certified or verbatim transcript, but rather represents only the context of the class or meeting, subject to the inherent limitations of realtime captioning. The primary focus of realtime captioning is general communication access and as such this document is not suitable, acceptable, nor is it intended for use in any type of legal proceeding. MICRC 06/30/21 9:00 am Meeting Captioned by Q&A Reporting, Inc., www.qacaptions.com >> CHAIR KELLOM: Good morning. As Chair of the Commission, I call this meeting of the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission to order at 9:00 a.m. This meeting is being live streamed at YouTube. For anyone in the public watching who would prefer to watch via a different platform than they are currently using, please visit our social media at Redistricting MI to find the link for viewing on YouTube. Our live stream today includes closed captioning. Closed captioning, ASL interpretation, and Spanish and Bengali and Arabic translation services will be provided for effective participation in this meeting. E-mail us at [email protected] for additional viewing options or details on accessing language translation services for this meeting. People with disabilities or needing other specific accommodations should also contact Redistricting at Michigan.gov. For purpose us of the public record, this meeting is also being transcribed, and those transcriptions will be made available and posted at Michigan.gov/MICRC along with the written public comment submissions. This meeting is being transcribed and posted on Michigan.gov and MICRC along with written public submissions. -

How to Plan Your Vermont Wedding

How to Plan Your Vermont Wedding Practical Tips & Honest Advice by Vermont Wedding Expert, Alison Ellis floralartvt.com Welcome to Vermont. Congratulations on your engagement! You’re getting married in Vermont which means you are a lover of the outdoors, a nature enthusiast, a hiker, a skier or rider, a college alum, a native-Vermonter or simply that you want to surround yourselves and your guests with a beautiful setting. VT is an incredible destination. My intention for putting these tips together for you is simple: Planning a wedding takes a lot of work & you’ve never done this before. This guide will help streamline your planning process…whether you’re planning from in-state or across the country. Here are 10 Essential Planning Tips based on over 14 years in the Vermont wedding industry. (I also speak from personal experience since my husband and I planned our own Vermont wedding in 2003.) I want to help set you on the right path & jumpstart your planning. You deserve the wedding of your dreams…so let’s get started. floralartvt.com #1 Location, location, location. Truly, your first step is to choose your venue. Your location determines so much about your wedding day. Do they provide tables? Have an in-house caterer? Each site has its own attributes & potential challenges so you need to lock down a date & place before you can do anything else. Visit your site around the time of year you plan to marry. You’ll see what’s in bloom, surrounding views, and whether there are any aspects of the environment that detract from the aesthetic. -

The Music Industry?

Contents 02!Forewords 04!Executive Summary 07!Data Comes of Age 24!DSP Dashboards 28!Data and the Charts 31!Practical Tips 34!Data Startups to Watch Forewords Geoff Taylor, chief executive of the BPI, and Kim Bayley, chief executive of ERA, on why big-data and analytics matter for labels, artists and digital 1 service providers alike Forewords Kim Bayley, CEO Geoff Taylor, CEO Entertainment Retailers Association BPI and BRIT Awards Much has been written about how digital music services including What powers the UK’s exceptional success in producing global hit records? Spotify, Amazon, Apple, Deezer and Google have helped return a music First of all, of course, the natural talent, open-mindedness and originality of industry whose decline once seemed terminal into growth again. our songwriters, producers and performers. But creating consistent commercial success also means relentless investment in A&R, an appetite But while digital services are proving their worth in terms of revenue, for risk-taking informed by years of experience and judgement, and their greatest contribution may yet turn out to be the vast quantities of innovative, expert marketing and promotion. data they generate about music fans’ preferences and listening habits. Increasingly, data, in all its forms – spanning metadata to big data – is Not only does this data allow them to hone their services, optimise playing a key role in shaping this process. As streaming comes to playlists and generate insights which could lead to new, value-added dominate music consumption, data is becoming a progressively more offerings, it is also potentially game-changing for the supply side of the important part of the process of producing and marketing music and, business, taking some guesswork out of what has always been a hit and arguably, one of the determinants of a song’s popularity. -

Media® JUNE 1, 2002 / VOLUME 20 / ISSUE 23 / £3.95 / EUROS 6.5

Music Media® JUNE 1, 2002 / VOLUME 20 / ISSUE 23 / £3.95 / EUROS 6.5 THE MUCH ANTICIPATED NEW ALBUM 10-06-02 INCLUDES THE SINGLE 'HERE TO STAY' Avukr,m',L,[1] www.korntv.com wwwamymusweumpecun IMMORTam. AmericanRadioHistory.Com System Of A Down AerialscontainsThe forthcoming previously single unreleased released and July exclusive 1 Iostprophetscontent.Soldwww.systemofadown.com out AtEuropean radio now. tour. theFollowing lostprophets massive are thefakesoundofprogressnow success on tour in thethroughout UK and Europe.the US, featuredCatch on huge the new O'Neill single sportwear on"thefakesoundofprogress", MTVwww.lostprophets.com competitionEurope during running May. CreedOne Last Breath TheCommercialwww.creednet.com new single release from fromAmerica's June 17.biggest band. AmericanRadioHistory.Com TearMTVDrowning Europe Away Network Pool Priority! Incubuswww.drowningpool.comCommercialOn tour in Europe release now from with June Ozzfest 10. and own headlining shows. CommercialEuropean release festivals fromAre in JuneAugust.You 17.In? www.sonymusiceurope.cornSONY MUSIC EUROPE www.enjoyincubus.com Music Mediae JUNE 1, 2002 / VOLUME 20 / ISSUE 23 / £3.95 / EUROS 6.5 AmericanRadioHistory.Com T p nTA T_C ROCK Fpn"' THE SINGLE THE ALBUM A label owned by Poko Rekords Oy 71e um!010111, e -e- Number 1in Finland for 4 weeks Number 1in Finland Certified gold Certified gold, soon to become platinum Poko Rekords Oy, P.O. Box 483, FIN -33101 Tampere, Finland I Tel: +358 3 2136 800 I Fax: +358 3 2133 732 I Email: [email protected] I Website: www.poko.fi I www.pariskills.com Two rriot girls and a boy present: Album A label owned by Poko Rekords Oy \member of 7lit' EMI Cji0//p "..rriot" AmericanRadioHistory.Com UPFRONT Rock'snolonger by Emmanuel Legrand, Music & Media editor -in -chief Welcome to Music & Media's firstspecial inahard place issue of the year-an issue that should rock The fact that Ozzy your socks off. -

Rita Ora Rip Free Mp3 Downloads

Rita ora rip free mp3 downloads ( MB) Stream and Download song R.I.P. by United Kingdom artist Rita Ora Ft. Tinie Tempah on Dawn Foxes Music - Watch the video, get the download or listen to Rita Ora – R.I.P. (feat. Tinie Tempah) for free. R.I.P. (feat. Tinie Tempah) appears on the album ORA (Deluxe. R.i.p. Ft. Tinie Tempah. Artist: Rita Ora. MB · R.i.p. (ft. Tinie Tempah) (gregor Salto Us Radio Edit). Artist: Rita Ora. MB. Rip. Artist: Rita Ora Ft. Tinie Tempah. MB · Rip. Artist: Rita Ora Feat. Tinie Tempah. MB. Advertisement. Related Searches. Rita Ora Feat. Tinie Tempah R.I.P free mp3 download and stream. Download Rita Ora Rip, MB Mp3 Single Track Rita Ora Rip Released On Download This Song In Mp3 And Othe Available Formats. Download Rita Ora R I P Mp3clan Com, MB Mp3 Single Track Rita Ora R I P Mp3clan Com Released On Download This Song In Mp3 And Othe Available. Stream R.I.P. (ft. Tinie Tempah) by Rita Ora from desktop or your mobile device. Buy R.I.P.: Read 2 Digital Music Reviews - Start your day free trial of Unlimited to listen to this album plus tens of Add to MP3 Cart . Haven't heard much more of Rita Ora's music but will be looking for more in the future. Download "R.I.P." on iTunes right now! Click here: More Rita Ora on iTunes. Tinie Tempah Rip Free Mp3 Download. Free download Rita Ora Tinie Tempah Rip Free Mp3 Download mp3 for free Tinie Tempah - R. -

Sweet 16 Hot List

Sweet 16 Hot List Song Artist Happy Pharrell Best Day of My Life American Authors Run Run Run Talk Dirty to Me Jason Derulo Timber Pitbull Demons & Radioactive Imagine Dragons Dark Horse Katy Perry Find You Zedd Pumping Blood NoNoNo Animals Martin Garrix Empire State of Mind Jay Z The Monster Eminem Blurred Lines We found Love Rihanna/Calvin Love Me Again John Newman Dare You Hardwell Don't Say Goodnight Hot Chella Rae All Night Icona Pop Wild Heart The Vamps Tennis Court & Royals Lorde Songs by Coldplay Counting Stars One Republic Get Lucky Daft punk Sexy Back Justin Timberland Ain't it Fun Paramore City of Angels 30 Seconds Walking on a Dream Empire of the Sun If I loose Myself One Republic (w/Allesso mix) Every Teardrop is a Waterfall mix Coldplay & Swedish Mafia Hey Ho The Lumineers Turbulence Laidback Luke Steve Aoki Lil Jon Pursuit of Happiness Steve Aoki Heads will roll Yeah yeah yeah's A-trak remix Mercy Kanye West Crazy in love Beyonce and Jay-z Pop that Rick Ross, Lil Wayne, Drake Reason Nervo & Hook N Sling All night longer Sammy Adams Timber Ke$ha, Pitbull Alive Krewella Teach me how to dougie Cali Swag District Aye ladies Travis Porter #GETITRIGHT Miley Cyrus We can't stop Miley Cyrus Lip gloss Lil mama Turn down for what Laidback Luke Get low Lil Jon Shots LMFAO We found love Rihanna Hypnotize Biggie Smalls Scream and Shout Cupid Shuffle Wobble Hips Don’t Lie Sexy and I know it International Love Whistle Best Love Song Chris Brown Single Ladies Danza Kuduro Can’t Hold Us Kiss You One direction Don’t You worry Child Don’t -

How to Think About Science.” Our Guest Is Brian Wynne of Lancaster University in the North of England

IDEAS HOW TO THINK ABOUT SCIENCE: BRIAN WYNNE Paul Kennedy colleagues. Many of them were studying what goes on in I'm Paul Kennedy, and this is Ideas on “How to Think scientific laboratories or analyzing scientific About Science.” Technological science exerts a pervasive controversies⎯trying to observe scientific knowledge influence on contemporary life. It determines much of still, as it were, under construction. Brian Wynne wanted what we do, and almost all of how we do it. Yet science to understand how scientific knowledge exerts its and technology lie almost completely outside the realm of authority in public arenas. I interviewed Brian Wynne in political decision. No electorate ever voted to split atoms the fall of 2006. Fighting a bad cold, he told me a little of or insert DNA from one organism into another. No his story. He grew up in a village in the northwest of legislature ever authorized the iPod or the internet. Our England, and his academic ability got him to Cambridge civilization, consequently, is caught in a profound where in 1971 he completed a PhD in material science, the paradox. We glorify freedom and choice, but submit to the branch of physics that studies the properties of transformation of our culture by technoscience as a virtual engineering materials. Up to that point, he said, he had fate. Today on Ideas, we explore the relations between never really thought about the politics of science. But then politics and scientific knowledge, as we continue with our he had a fateful conversation. series “How To Think About Science.” Our guest is Brian Wynne of Lancaster University in the north of England. -

This Is How We Do: Living and Learning in an Appalachian Experimental Music Scene

THIS IS HOW WE DO: LIVING AND LEARNING IN AN APPALACHIAN EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC SCENE A Thesis by SHANNON A.B. PERRY Submitted to the Graduate School Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS MAY 2011 Center for Appalachian Studies THIS IS HOW WE DO: LIVING AND LEARNING IN AN APPALACHIAN EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC SCENE A Thesis by SHANNON A.B. PERRY May 2011 APPROVED BY: ________________________________ Fred J. Hay Chairperson, Thesis Committee ________________________________ Susan E. Keefe Member, Thesis Committee ________________________________ Patricia D. Beaver Member, Thesis Committee ________________________________ Patricia D. Beaver Director, Center for Appalachian Studies ________________________________ Edelma D. Huntley Dean, Research and Graduate Studies Copyright by Shannon A.B. Perry 2011 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT THIS IS HOW WE DO: LIVING AND LEARNING IN AN APPALACHIAN EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC SCENE (2011) Shannon A.B. Perry, A.B. & B.S.Ed., University of Georgia M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Fred J. Hay At the grassroots, Appalachian music encompasses much more than traditional music genres, like old-time and bluegrass. While these prevailing musics continue to inform most popular and scholarly understandings of the region’s musical heritage, many contemporary scholars dismiss such narrow definitions of “Appalachian music” as exclusionary and inaccurate. Many researchers have, thus, sought to broaden current understandings of Appalachia’s diverse contemporary and historical cultural landscape as well as explore connections between Appalachian and other regional, national, and global cultural phenomena. In April 2009, I began participant observation and interviewing in an experimental music scene unfolding in downtown Boone, North Carolina.