Netherlands Antilles: Trade and Integration with CARICOM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Code List 11 Invoice Currency

Code list 11 Invoice currency Alphabetical order Code Code Alfa Alfa Country / region Country / region A BTN Bhutan ngultrum BOB Bolivian boliviano AFN Afghan new afghani BAM Bosnian mark ALL Albanian lek BWP Botswanan pula DZD Algerian dinar BRL Brazilian real USD American dollar BND Bruneian dollar AOA Angolan kwanza BGN Bulgarian lev ARS Argentinian peso BIF Burundi franc AMD Armenian dram AWG Aruban guilder AUD Australian dollar C AZN Azerbaijani new manat KHR Cambodian riel CAD Canadian dollar B CVE Cape Verdean KYD Caymanian dollar BSD Bahamian dollar XAF CFA franc of Central-African countries BHD Bahraini dinar XOF CFA franc of West-African countries BBD Barbadian dollar XPF CFP franc of Oceania BZD Belizian dollar CLP Chilean peso BYR Belorussian rouble CNY Chinese yuan renminbi BDT Bengali taka COP Colombian peso BMD Bermuda dollar KMF Comoran franc Code Code Alfa Alfa Country / region Country / region CDF Congolian franc CRC Costa Rican colon FKP Falkland Islands pound HRK Croatian kuna FJD Fijian dollar CUC Cuban peso CZK Czech crown G D GMD Gambian dalasi GEL Georgian lari DKK Danish crown GHS Ghanaian cedi DJF Djiboutian franc GIP Gibraltar pound DOP Dominican peso GTQ Guatemalan quetzal GNF Guinean franc GYD Guyanese dollar E XCD East-Caribbean dollar H EGP Egyptian pound GBP English pound HTG Haitian gourde ERN Eritrean nafka HNL Honduran lempira ETB Ethiopian birr HKD Hong Kong dollar EUR Euro HUF Hungarian forint F I Code Code Alfa Alfa Country / region Country / region ISK Icelandic crown LAK Laotian kip INR Indian rupiah -

People's Democratic Republic of Algeria

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Higher School of Management Sciences Annaba A Course of Business English for 1st year Preparatory Class Students Elaborated by: Dr GUERID Fethi The author has taught this module for 4 years from the academic year 2014/2015 to 2018/2019 Academic Year 2020/2021 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents...………………………………………………………….….I Acknowelegments……………………………………………………………....II Aim of the Course……………………………………………………………..III Lesson 1: English Tenses………………………………………………………..5 Lesson 2: Organizations………………………………………………………..13 Lesson 3: Production…………………………………………………………...18 Lesson 4: Distribution channels: Wholesale and Retail………………………..22 Lesson 5: Marketing …………………………………………………………...25 Lesson 6: Advertising …………………………………………………………28 Lesson 7: Conditional Sentences………………………………………………32 Lesson 8: Accounting1…………………………………………………………35 Lesson 9: Money and Work……………………………………………………39 Lesson 10: Types of Business Ownership……………………………………..43 Lesson 11: Passive voice……………………………………………………….46 Lesson 12: Management……………………………………………………….50 SUPPORTS: 1- Grammatical support: List of Irregular Verbs of English………..54 2- List of Currencies of the World………………………………….66 3- Business English Terminology in English and French………….75 References and Further Reading…………………………………………….89 I 2 Acknowledgments I am grateful to my teaching colleagues who preceded me in teaching this business English module at our school. This contribution is an addition to their efforts. I am thankful to Mrs Benghomrani Naziha, who has contributed before in designing English programmes to different levels, years and classes at Annaba Higher School of Management Sciences. I am also grateful to the administrative staff for their support. II 3 Aim of the Course The course aims is to equip 1st year students with the needed skills in business English to help them succeed in their study of economics and business and master English to be used at work when they finish the study. -

Salada Foods Jamaica Ltd

Salada Foods Jamaica Ltd. Notes to the Financial Statements 30 September 2002 1 Company Identification and Principal Activity The company, which is incorporated in Jamaica, is the sole manufacturer of instant coffee in Jamaica. Sales of instant coffee and roasted and ground beans represent approximately 80% of the company's and the group's turnover. All amounts are stated in Jamaican dollars. 2 Significant Accounting Policies (a) Basis of preparation These financial statements have been prepared in accordance with and comply with Jamaican Accounting Standards, and have been prepared under the historical cost convention, as modified by the revaluation of certain fixed assets. (b) Use of estimates The preparation of financial statements in conformity with Jamaican generally accepted accounting principles requires management to make estimates and assumptions that affect the reported amounts of assets and liabilities and disclosure of contingent assets and liabilities at the date of the financial statements and the reported amounts of revenue and expenses during the reporting period. Actual results could differ from those estimates. (c) Basis of consolidation The group's financial statements present the results of operations and financial position of the company and two of its wholly owned subsidiaries, Coffee Company of Jamaica Limited and Shirriff's (Jamaica) Limited. The excess of the cost of shares in the subsidiaries over the book value of the net assets acquired has been charged against shareholders' interests. (d) Investment in subsidiaries Investments by the holding company in subsidiaries are stated at cost. (e) Financial instruments Financial instruments carried on the balance sheet include receivables, group balances, payables and short and long-term loans. -

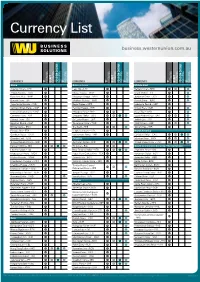

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Appendix 1 Political Forms of the Caribbean Compiled by Yarimar Bonilla, Rutgers University

Appendix 1 Political Forms of the Caribbean Compiled by Yarimar Bonilla, Rutgers University Jurisdiction Political Status and Important Historical Dates Monetary Unit * = on UN list of non-self- governing territories Constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Seceded from the Aruba Netherlands Antilles in 1986 with plans for independence, but independence was Aruban florin (AFL) postponed indefinitely in 1994. Constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Former seat of the Antillean guilder N Curacao Netherlands Antilles central government. Became an autonomous country within (ANG) E the kingdom of the Netherlands in 2010. T Constituent Country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Part of the Windward H Sint Maarten Islands territory within the Netherland Antilles until 1983. Became an autonomous ANG E country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 2010. R L Special municipality of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Formerly part of the A Bonaire Netherlands Antilles. Became a special municipality within the Kingdom of the US dollar (USD) N Netherlands in 2010. D Special municipality of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Part of the Windward S Saba Islands territory within the Netherland Antilles until 1983. Became a special USD municipality within the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 2010. Special municipality of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Part of the Windward Sint Eustatius Islands territory within the Netherland Antilles until 1983. Became a special USD municipality within the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 2010 Overseas territory of the United Kingdom. Formerly part of the British Leeward Island colonial federation as the colony of Saint Cristopher-Nevis-Anguilla. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

REGISTRATION DOCUMENT 2016/2017 and Annual Financial Report

2017 REGISTRATION DOCUMENT INCLUDING THE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 2016/2017 CONTENTS 15OVERVIEW OF THE GROUP 3 CONSOLIDATED 1.1 Key figures 4 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 1.2 History 5 AT 31 MARCH 2017 123 1.3 Shareholding structure 6 5.1 Consolidated income statement 124 1.4 The Group’s activities 7 5.2 Consolidated statement of comprehensive 1.5 Related-party transactions and material income 125 contracts 10 5.3 Consolidated statement of financial position 126 1.6 Risk factors and insurance policy 12 5.4 Change in consolidated shareholders’ equity 127 5.5 Consolidated statement of cash flows 128 5.6 Notes to the consolidated financial 2 CORPORATE SOCIAL statements 129 RESPONSIBILITY (CSR) 19 5.7 Statutory auditors’ report on the consolidated financial statements 173 Introduction: Chairman’s Commitment 20 2.1 The Group’s policy and commitments 21 2.2 Employee-related information 25 6 COMPANY FINANCIAL 2.3 Environmental information 31 STATEMENTS 2.4 Societal information 45 AT 31 MARCH 2017 175 2.5 Table of environmental indicators by site 50 6.1 Balance sheet 176 2.6 2020 targets 53 6.2 Income statement 177 2.7 Note on methodology for reporting environmental and employee-related 6.3 Cash flow statement 178 indicators 54 6.4 Financial results for the last five years 179 2.8 Cross-reference tables 57 6.5 Notes to the financial statements 180 2.9 Independent verifier’s report 6.6 Statutory auditors’ report on the financial on consolidated social, environmental statements 190 and societal information presented in the management report 61 7 INFORMATION 3 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE ON THE COMPANY AND INTERNAL CONTROL 65 AND THE CAPITAL 191 7.1 General information about the Company 192 3.1 Composition of administrative and management bodies 66 7.2 Memorandums and Articles of Association 192 3.2 Report of the Chairman of the Board 7.3 General information about the share capital 194 of Directors 77 7.4 Shareholding and stock market information 202 3.3 Statutory Auditors’ report, prepared in 7.5 Items liable to have an impact in the event accordance with Article L. -

FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name*

FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name* Afghanistan AFA Afghani Albania ALL Lek Algeria DZD Algerian Dinar Amer Samoa USD US Dollar Andorra ADP Andorran Peseta Angola AON New Kwanza Anguilla XCD East Caribbean Dollar Antigua Barb XCD East Caribbean Dollar Argentina ARS Argentine Peso Armenia AMD Armeniam Dram Aruba AWG Aruban Guilder Australia AUD Australian Dollar Austria ATS Schilling Azerbaijan AZM Azerbaijanian Manat Bahamas BSD Bahamian Dollar Bahrain BHD Bahraini Dinar Bangladesh BDT Taka Barbados BBD Barbados Dollar Belarus BYB Belarussian Ruble Belgium BEF Belgian Franc Belize BZD Belize Dollar Benin XOF CFA Franc Bermuda BMD Bermudian Dollar Bhutan BTN Ngultrum Bolivia BOB Boliviano Botswana BWP Pula Br Ind Oc Tr USD US Dollar Br Virgin Is USD US Dollar Brazil BRL Brazilian Real Brunei Darsm BND Brunei Dollar Bulgaria BGN New Lev Burkina Faso XOF CFA Franc Burundi BIF Burundi Franc Côte dIvoire XOF CFA Franc Cambodia KHR Riel Cameroon XAF CFA Franc Canada CAD Canadian Dollar Cape Verde CVE Cape Verde Escudo Cayman Is KYD Cayman Islands Dollar Cent Afr Rep XAF CFA Franc Chad XAF CFA Franc Channel Is GBP Pound Sterling Chile CLP Chilean Peso China CNY Yuan Renminbi China, Macao MOP Pataca China,H.Kong HKD Hong Kong Dollar China,Taiwan TWD New Taiwan Dollar Christmas Is AUD Australian Dollar Cocos Is AUD Australian Dollar Colombia COP Colombian Peso Comoros KMF Comoro Franc FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name* Congo Dem R CDF Franc Congolais Congo Rep XAF CFA Franc Cook Is NZD New Zealand Dollar Costa Rica -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

ANNEX a to the 1998 FX and CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED and RESTATED AS of NOVEMBER 19, 2017 I

ANNEX A to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions _________________________ Amended and Restated November 19, 2017 Amended March 16, 2020 INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. EMTA, INC. TRADE ASSOCIATION FOR THE EMERGING MARKETS Copyright © 2000-2020 by INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. EMTA, INC. ISDA and EMTA consent to the use and photocopying of this document for the preparation of agreements with respect to derivative transactions and for research and educational purposes. ISDA and EMTA do not, however, consent to the reproduction of this document for purposes of sale. For any inquiries with regard to this document, please contact: INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. 10 East 53rd Street New York, NY 10022 www.isda.org EMTA, Inc. 405 Lexington Avenue, Suite 5304 New York, N.Y. 10174 www.emta.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION TO ANNEX A TO THE 1998 FX AND CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED AND RESTATED AS OF NOVEMBER 19, 2017 i ANNEX A CALCULATION OF RATES FOR CERTAIN SETTLEMENT RATE OPTIONS SECTION 4.3. Currencies 1 SECTION 4.4. Principal Financial Centers 6 SECTION 4.5. Settlement Rate Options 9 A. Emerging Currency Pair Single Rate Source Definitions 9 B. Non-Emerging Currency Pair Rate Source Definitions 21 C. General 22 SECTION 4.6. Certain Definitions Relating to Settlement Rate Options 23 SECTION 4.7. Corrections to Published and Displayed Rates 24 INTRODUCTION TO ANNEX A TO THE 1998 FX AND CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED AND RESTATED AS OF NOVEMBER 19, 2017 Annex A to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions ("Annex A"), originally published in 1998, restated in 2000 and amended and restated as of the date hereof, is intended for use in conjunction with the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions, as amended and updated from time to time (the "FX Definitions") in confirmations of individual transactions governed by (i) the 1992 ISDA Master Agreement and the 2002 ISDA Master Agreement published by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc. -

Annual Report 2004

ANNUAL REPORT 2004 Report and Statement of Accounts for the Year Ended 31 December 2004 Mission Statement The mission of the Bank of Jamaica is to formulate and implement monetary and regulatory policies to safeguard the value of the domestic currency and to ensure the soundness and development of the financial system by being a strong and efficient organisation with highly motivated and professional employees working for the benefit of the people of Jamaica. BANK OF JAMAICA NETHERSOLE PLACE KINGSTON 31 March 2005 Dr. The Hon. Omar Davies Minister of Finance & Planning National Heroes Circle Kingston 4 Dear Minister: In accordance with Section 44 (1) of the Bank of Jamaica Act, 1960, I have the honour of transmitting herewith the Bank’s Report for the year 2004 and a copy of the Statement of the Bank’s Accounts as at 31 December 2004 duly certified by the Auditors. Yours sincerely, Derick Latibeaudiere Governor PRINCIPAL OFFICERS GOVERNOR Mr. Derick Latibeaudiere DEPUTY GOVERNORS 1. Mrs. Audrey Anderson - Financial Institutions Supervisory Division 2. Mr. Colin Bullock - Research & Economic Programming Division Banking & Market Operations Division 3. Mr. Rudolph Muir - General Counsel & Bank Secretary, Corporate Secretary’s Division GENERAL MANAGER Mr. Kenloy Peart DIVISION CHIEFS 1. Mrs. Myrtle Halsall - Research & Economic Programming Division 2. Mrs. Gayon Hosin - Financial Institutions Supervisory Division 3. Mr. Herbert Hylton - Finance & Technology 4. Mrs. Faith Stewart - Financial Services Sub-Division Banking & Market Operations Division SENIOR DIRECTORS 1. Mr. Randolph Dandy - Senior Legal Counsel Legal Department 2. Mrs. Natalie Haynes - Senior Director Financial Markets Sub-Division Banking & Market Operations Division 3. -

EXCHANGE RATE POLICY in the EASTERN CARIBBEAN by William Loehr Loehr and Associates, Inc. 1580 Garst Lane Ojai, CA 93023 (8

EXCHANGE RATE POLICY IN THE EASTERN CARIBBEAN by William Loehr Loehr and Associates, Inc. 1580 Garst Lane Ojai, CA 93023 (805) 646-4122 (0s) for US AID RDO/C Bridgetown, Barbados Under Contract: 538-0000-C-00-6012- March 10, 1986 INDEX Page Executive Summary Section 1: Introduction Section 2: An Assessment of Overvaluation of the EC Dollar 3 2.1 Concepts 3 2.2 Findings: Exchange Market Conditions 8 2,3 Findings: Real Exchange Rate 12 2.4 An Assessment 27 Section 3: Real Exchange Rates in The OECS 30 3.1 Real Exchange Rates 30 3.2 Nominal and Real Effective Exchange Rates 44 3.3 Real Effective Exchange Rate Results 51 3.4 Summary 64 Section 4: Exchange Market Options 65 4.1 Introduction 65 4.2 The Devaluation Option 69 4.3 Alternative Exchange Regime Arrangements 91 4.4 Summary 99 Section 5: Non-Exchange Market Options 103 5.1 Non-Exchange Market Policies 103 5.2 Problem Countries 107 5.3 Summary 112 Section 6: Conclusions and Recommendations 113 6.1 Conclusions 113 6.2 Recommendations 114 Bibliography 117 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This research was designed to determine whether or not the Eastern Caribbean dollar ( EC dollar ) is overvalued and whether AID should be advocating a devaluation of the EC dollar. A secondary concern was with the alternative forms that the exchange regime for the EC dollar could take. The EC dollar has been pegged to the U.S. dollar since 1976 at the rate of EC$ 2.70 = US$ 1.00. Alternatives include devaluation of that peg, pegging to some other standard or allowing the EC dollar to float.