Extinctions and Biodiversity in the Fossil Record

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Instability and Tipping Points in the Late Devonian

Archived version from NCDOCKS Institutional Repository – http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/ Sarah K. Carmichael, Johnny A. Waters, Cameron J. Batchelor, Drew M. Coleman, Thomas J. Suttner, Erika Kido, L.M. Moore, and Leona Chadimová, (2015) Climate instability and tipping points in the Late Devonian: Detection of the Hangenberg Event in an open oceanic island arc in the Central Asian Orogenic Belt, Gondwana Research The copy of record is available from Elsevier (18 March 2015), ISSN 1342-937X, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2015.02.009. Climate instability and tipping points in the Late Devonian: Detection of the Hangenberg Event in an open oceanic island arc in the Central Asian Orogenic Belt Sarah K. Carmichael a,*, Johnny A. Waters a, Cameron J. Batchelor a, Drew M. Coleman b, Thomas J. Suttner c, Erika Kido c, L. McCain Moore a, and Leona Chadimová d Article history: a Department of Geology, Appalachian State University, Boone, NC 28608, USA Received 31 October 2014 b Department of Geological Sciences, University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill, Received in revised form 6 Feb 2015 Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3315, USA Accepted 13 February 2015 Handling Editor: W.J. Xiao c Karl-Franzens-University of Graz, Institute for Earth Sciences (Geology & Paleontology), Heinrichstrasse 26, A-8010 Graz, Austria Keywords: d Institute of Geology ASCR, v.v.i., Rozvojova 269, 165 00 Prague 6, Czech Republic Devonian–Carboniferous Chemostratigraphy Central Asian Orogenic Belt * Corresponding author at: ASU Box 32067, Appalachian State University, Boone, NC 28608, USA. West Junggar Tel.: +1 828 262 8471. E-mail address: [email protected] (S.K. -

Cretaceous–Paleogene Extinction Event (End Cretaceous, K-T Extinction, Or K-Pg Extinction): 66 MYA At

Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (End Cretaceous, K-T extinction, or K-Pg extinction): 66 MYA at • About 17% of all families, 50% of all genera and 75% of all species became extinct. • In the seas it reduced the percentage of sessile animals to about 33%. • All non-avian dinosaurs became extinct during that time. • Iridium anomaly in sediments may indicate comet or asteroid induced extinctions Triassic–Jurassic extinction event (End Triassic): 200 Ma at the Triassic- Jurassic transition. • About 23% of all families, 48% of all genera (20% of marine families and 55% of marine genera) and 70-75% of all species went extinct. • Most non-dinosaurian archosaurs, most therapsids, and most of the large amphibians were eliminated • Dinosaurs had with little terrestrial competition in the Jurassic that followed. • Non-dinosaurian archosaurs continued to dominate aquatic environments • Theories on cause: 1.) Gradual climate change, perhaps with ocean acidification has been implicated, but not proven. 2.) Asteroid impact has been postulated but no site or evidence has been found. 3.) Massive volcanics, flood basalts and continental margin volcanoes might have damaged the atmosphere and warmed the planet. Permian–Triassic extinction event (End Permian): 251 Ma at the Permian-Triassic transition. Known as “The Great Dying” • Earth's largest extinction killed 57% of all families, 83% of all genera and 90% to 96% of all species (53% of marine families, 84% of marine genera, about 96% of all marine species and an estimated 70% of land species, • The evidence of plants is less clear, but new taxa became dominant after the extinction. -

Meet the Gilded Lady 2 Mummies Now Open

Member Magazine Spring 2017 Vol. 42 No. 2 Mummies meet the gilded lady 2 mummies now open Seeing Inside Today, computerized inside of mummies, revealing CT scans of the Gilded Lady tomography (CT) scanning details about the person’s reveal that she was probably offers researchers glimpses age, appearance, and health. in her forties. They also suggest of mummified individuals “Scans like these are noninvasive, that she may have suffered like never before. By combining they’re repeatable, and they from tuberculosis, a common thousands of cross-sectioned can be done without damaging disease at the time. x-ray images, CT scans let the history that we’re trying researchers examine the to understand,” Thomas says. Mummy #30007, known as the Gilded Lady, is one of the most beautifully preserved mummies from The Field Museum’s collection, and one of 19 now on view in the special exhibition Mummies. For decades, keeping mummies like this one well preserved also meant severely limiting the ability of researchers to study them. The result is that little was known about the Gilded Lady beyond what could be gleaned from the mummy’s exterior, with its intricate linen bindings, gilded headdress, and painted facial features. Exterior details do offer some clues. The mummy dates from 30 BC–AD 395, a period when Egypt was a province of the Roman Empire. While the practice of mummification endured in Egypt, it was being transformed by Roman influences. Before the Roman era, for example, mummies had been placed in wooden coffins, while the Gilded Lady is preserved in only linen wrappings and cartonnage, a papier mâché-like material. -

Assessing Symbiont Extinction Risk Using Cophylogenetic Data 2 3 Jorge Doña1 and Kevin P

1 Assessing symbiont extinction risk using cophylogenetic data 2 3 Jorge Doña1 and Kevin P. Johnson1 4 5 1. Illinois Natural History Survey, Prairie Research Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 6 1816 S. Oak St., Champaign, IL 61820, USA 7 8 *Corresponding authors: Jorge Doña & Kevin Johnson; e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] 9 10 Abstract: Symbionts have a unique mode of life that has attracted the attention of ecologists and 11 evolutionary biologists for centuries. As a result of this attention, these disciplines have produced 12 a mature body of literature on host-symbiont interactions. In contrast, the discipline of symbiont 13 conservation is still in a foundational stage. Here, we aim to integrate methodologies on symbiont 14 coevolutionary biology with the perspective of conservation. We focus on host-symbiont 15 cophylogenies, because they have been widely used to study symbiont diversification history and 16 contain information on symbiont extinction. However, cophylogenetic information has never been 17 used nor adapted to the perspective of conservation. Here, we propose a new statistic, 18 “cophylogenetic extinction rate” (Ec), based on coevolutionary knowledge, that uses data from 19 event-based cophylogenetic analyses, and which could be informative to assess relative symbiont 20 extinction risks. Finally, we propose potential future research to further develop estimation of 21 symbiont extinction risk from cophylogenetic analyses and continue the integration of this existing 22 knowledge of coevolutionary biology and cophylogenetics into future symbiont conservation 23 studies and practices. 24 25 Keywords: coevolution, coextinction risk, conservation biology, cophylogenies, host-symbiont 26 interactions, parasites. -

Place Names Describing Fossils in Oral Traditions

Place names describing fossils in oral traditions ADRIENNE MAYOR Classics Department, Stanford University, Stanford CA 94305 (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: Folk explanations of notable geological features, including fossils, are found around the world. Observations of fossil exposures (bones, footprints, etc.) led to place names for rivers, mountains, valleys, mounds, caves, springs, tracks, and other geological and palaeonto- logical sites. Some names describe prehistoric remains and/or refer to traditional interpretations of fossils. This paper presents case studies of fossil-related place names in ancient and modern Europe and China, and Native American examples in Canada, the United States, and Mexico. Evidence for the earliest known fossil-related place names comes from ancient Greco-Roman and Chinese literature. The earliest documented fossil-related place name in the New World was preserved in a written text by the Spanish in the sixteenth century. In many instances, fossil geonames are purely descriptive; in others, however, the mythology about a specific fossil locality survives along with the name; in still other cases the geomythology is suggested by recorded traditions about similar palaeontological phenomena. The antiquity and continuity of some fossil-related place names shows that people had observed and speculated about miner- alized traces of extinct life forms long before modern scientific investigations. Traditional place names can reveal heretofore unknown geomyths as well as new geologically-important sites. Traditional folk names for geological features in the Named fossil sites in classical antiquity landscape commonly refer to mythological or and modern Greece legendary stories that accounted for them (Vitaliano 1973). Landmarks notable for conspicuous fossils Evidence for the practice of naming specific fossil have been named descriptively or mythologically locales can be found in classical antiquity. -

The Role of Extinction in Evolution DAVID M

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 91, pp. 6758-6763, July 1994 Colloquium Paper Ths paper was presented at a colloquium entled "Tempo and Mode in Evolution" organized by Walter M. Fitch and Francisco J. Ayala, held January 27-29, 1994, by the National Academy of Sciences, in Irvine, CA. The role of extinction in evolution DAVID M. RAuP Department of Geophysical Sciences, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637 ABSTRACT The extinction of species is not normally must remember what has already been said on the probable consideed an important element of neodarwinian theory, in wide intervals of time between our consecutive formations; contrast to the opposite phenomenon, specatlon. This is sur- and in these intervals there may have been much slower prising in view of the special importance Darwin attced to extermination. (pp. 321-322) extinction, and because the number ofspecies extinctions in the Like his geologist colleague Charles Lyell, Darwin was history oflife is almost the same as the number oforiginations; contemptuous ofthose who thought extinctions were caused present-day biodiversity Is the result of a trivial surplus of by great catastrophes. cumulated over millions of years. For an evolu- tions, ... so profound is our ignorance, and so high our presump- tionary biologist to ignore extinction is probably as foolhardy tion, that we marvel when we hear of the extinction of an as for a demographer to ignore mortality. The past decade has organic being; and as we do not see the cause, we invoke seen a resurgence of interest in extinction, yet research on the cataclysms to desolate the world, or invent laws on the topic Is stifl at a reconnaissance level, and our present under- duration of the forms of life! (p. -

One Million Species Face Extinction

IN FOCUS NEWS But the excitement around cancer immuno therapies — two researchers won a Nobel prize last year for pioneering them — has been tempered after several partici- pants in US clinical trials died from side effects. Regulators around the world have moved slowly to approve the treatments for sale. The US Food and Drug Admin- istration has approved only three cancer immunotherapies so far, and the Chinese drug regulator has approved none. THE OCEAN AGENCY/XL CATLIN SEAVIEW SURVEY SEAVIEW CATLIN THE OCEAN AGENCY/XL Before 2016, Chinese regulations for the sale of cell therapies were ambiguous, and many hospitals sold the treatments to patients while safety and efficacy testing was still under way. Ren Jun, an oncolo- gist at the Beijing Shijitan Hospital Cancer Center, estimates that roughly one million people paid for such procedures. But the market came under scrutiny when it was revealed that a university student with Habitats such as coral reefs have been hit hard by pollution and climate change. a rare cancer had paid more than 200,000 yuan (US$30,000) for an experimental BIODIVERSITY immunotherapy, after seeing it promoted by a hospital on the Internet. The treatment was unsuccessful, and the student later died. The government cracked down on hospi- One million species tals selling cell therapies — although clinical trials in which participants do not pay for treatment were allowed to continue. face extinction GATHERING EVIDENCE Under the proposed regulations, roughly Landmark United Nations report finds that human activities 1,400 elite hospitals that conduct medical threaten ecosystems around the world. research, known as Grade 3A hospitals, would be able to apply for a licence to sell cell therapies, after proving that they BY JEFF TOLLEFSON in Paris to finalize and approve it. -

Global Catastrophic Risks Survey

GLOBAL CATASTROPHIC RISKS SURVEY (2008) Technical Report 2008/1 Published by Future of Humanity Institute, Oxford University Anders Sandberg and Nick Bostrom At the Global Catastrophic Risk Conference in Oxford (17‐20 July, 2008) an informal survey was circulated among participants, asking them to make their best guess at the chance that there will be disasters of different types before 2100. This report summarizes the main results. The median extinction risk estimates were: Risk At least 1 million At least 1 billion Human extinction dead dead Number killed by 25% 10% 5% molecular nanotech weapons. Total killed by 10% 5% 5% superintelligent AI. Total killed in all 98% 30% 4% wars (including civil wars). Number killed in 30% 10% 2% the single biggest engineered pandemic. Total killed in all 30% 10% 1% nuclear wars. Number killed in 5% 1% 0.5% the single biggest nanotech accident. Number killed in 60% 5% 0.05% the single biggest natural pandemic. Total killed in all 15% 1% 0.03% acts of nuclear terrorism. Overall risk of n/a n/a 19% extinction prior to 2100 These results should be taken with a grain of salt. Non‐responses have been omitted, although some might represent a statement of zero probability rather than no opinion. 1 There are likely to be many cognitive biases that affect the result, such as unpacking bias and the availability heuristic‒‐well as old‐fashioned optimism and pessimism. In appendix A the results are plotted with individual response distributions visible. Other Risks The list of risks was not intended to be inclusive of all the biggest risks. -

Evaluating the Frasnian-Famennian Mass Extinction: Comparing Brachiopod Faunas

Evaluating the Frasnian-Famennian mass extinction: Comparing brachiopod faunas PAUL COPPER Copper, P. 1998. Evaluating the Frasnian-Famennian mass extinction: Comparing bra- chiopod faunas.- Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 43,2,137-154. The Frasnian-Famennian (F-F) mass extinctions saw the global loss of all genera belonging to the tropically confined order Atrypida (and Pentamerida): though Famen- nian forms have been reported in the literafure, none can be confirmed. Losses were more severe during the Givetian (including the extinction of the suborder Davidsoniidina, and the reduction of the suborder Lissatrypidina to a single genus),but ońgination rates in the remaining suborder surviving into the Frasnian kept the group alive, though much reduced in biodiversity from the late Earb and Middle Devonian. In the terminal phases of the late Palmatolepis rhenana and P linguifurmis zones at the end of the Frasnian, during which the last few Atrypidae dechned, no new genera originated, and thus the Atrypida were extĘated. There is no evidence for an abrupt termination of all lineages at the F-F boundary, nor that the Atrypida were abundant at this time, since all groups were in decline and impoverished. Atypida were well established in dysaerobic, muddy substrate, reef lagoonal and off-reef deeper water settings in the late Givetian and Frasnian, alongside a range of brachiopod orders which sailed through the F-F boundary: tropical shelf anoxia or hypońa seems implausible as a cause for aĘpid extinction. Glacial-interglacial climate cycles recorded in South Ameńca for the Late Devonian, and their synchronous global cooling effect in low latitudes, as well as loss of the reef habitat and shelf area reduction, remain as the most likely combined scenarios for the mass extinction events. -

Viruses and the Origin of Microbiome Selection and Immunity

The ISME Journal (2017) 11, 835–840 © 2017 International Society for Microbial Ecology All rights reserved 1751-7362/17 www.nature.com/ismej PERSPECTIVE Viruses and the origin of microbiome selection and immunity Steven D Quistad1,2,3, Juris A Grasis1, Jeremy J Barr1,4 and Forest L Rohwer1 1Department of Biology, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA, USA; 2Laboratoire de Colloïdes et Matériaux Divisés (LCMD), Institute of Chemistry, Biology, and Innovation, ESPCI ParisTech/CNRS UMR 8231/PSL Research University, Paris, France; 3Laboratoire de Colloïdes et Matériaux Divisés (LCMD), Institute of Chemistry, Biology, and Innovation, ESPCI ParisTech/CNRS UMR 8231/PSL Research University, Paris, France and 4School of Biological Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia The last common metazoan ancestor (LCMA) emerged over half a billion years ago. These complex metazoans provided newly available niche space for viruses and microbes. Modern day contemporaries, such as cnidarians, suggest that the LCMA consisted of two cell layers: a basal endoderm and a mucus-secreting ectoderm, which formed a surface mucus layer (SML). Here we propose a model for the origin of metazoan immunity based on external and internal microbial selection mechanisms. In this model, the SML concentrated bacteria and their associated viruses (phage) through physical dynamics (that is, the slower flow fields near a diffusive boundary layer), which selected for mucin-binding capabilities. The concentration of phage within the SML provided the LCMA with an external microbial selective described by the bacteriophage adherence to mucus (BAM) model. In the BAM model, phage adhere to mucus protecting the metazoan host against invading, potentially pathogenic bacteria. -

Issue of the FOSSIL

Official Publication of The Fossils, The Historians of Amateur Journalism The Fossil Volume 116, No. 3, Whole No. 383 Sunnyvale, California April 2020 Fossil Profile My Ajay Mentors by Linda Donaldson FOSSIL EDITOR Dave Tribby has asked me to provide a the beginning of a long love affair. It was almost the few thoughts on my friends and mentors in the world last press I saw exit my door. of amateur journalism. Though I’m not active now, He also introduced me to ajayers in my hometown thanks mostly to vision problems that make it hard to of Portsmouth, Ohio: Karl X. Williams and Charlie read the bundles, I was fortunate Phillips. The two of them were to have had several good men happy to share or sell me some of tors. I am still a Fossil—it’s hard their treasure troves of type or to totally desert the realm. necessary equipment. Much has It started with the one and been written of Karl, a Lone only J. Hill Hamon, whom I met Scout young printer in the 1920s, as my Biology professor at AAPA founding father, and a Transylvania University in Lex Fossil. To this day I possess a pa ington, Kentucky in January of per cutter I bought from Katie, 1972. I didn’t start learning the Karl’s widow. I was employed printing part until a short term about five years as a rubber class in December of 1972. He set stamp maker by Karl’s daughter out lots of old type on the Bio Pam and soninlaw Gary. -

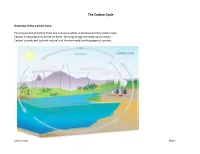

The Carbon Cycle

The Carbon Cycle Overview of the Carbon Cycle The movement of carbon from one area to another is the basis for the carbon cycle. Carbon is important for all life on Earth. All living things are made up of carbon. Carbon is produced by both natural and human-made (anthropogenic) sources. Carbon Cycle Page 1 Nature’s Carbon Sources Carbon is found in the Carbon is found in the lithosphere Carbon is found in the Carbon is found in the atmosphere mostly as carbon in the form of carbonate rocks. biosphere stored in plants and hydrosphere dissolved in ocean dioxide. Animal and plant Carbonate rocks came from trees. Plants use carbon dioxide water and lakes. respiration place carbon into ancient marine plankton that sunk from the atmosphere to make the atmosphere. When you to the bottom of the ocean the building blocks of food Carbon is used by many exhale, you are placing carbon hundreds of millions of years ago during photosynthesis. organisms to produce shells. dioxide into the atmosphere. that were then exposed to heat Marine plants use cabon for and pressure. photosynthesis. The organic matter that is produced Carbon is also found in fossil fuels, becomes food in the aquatic such as petroleum (crude oil), coal, ecosystem. and natural gas. Carbon is also found in soil from dead and decaying animals and animal waste. Carbon Cycle Page 2 Natural Carbon Releases into the Atmosphere Carbon is released into the atmosphere from both natural and man-made causes. Here are examples to how nature places carbon into the atmosphere.