Real Property Law Ralph E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk

Federal Trade Commission ftc.gov The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk Buying a home can be exciting. It also can be somewhat daunting, even if you’ve done it before. You will deal with mortgage options, credit reports, loan applications, contracts, points, appraisals, change orders, inspections, warranties, walk-throughs, settlement sheets, escrow accounts, recording fees, insurance, taxes...the list goes on. No doubt you will hear and see words and terms you’ve never heard before. Just what do they all mean? The Federal Trade Commission, the agency that promotes competition and protects consumers, has prepared this glossary to help you better understand the terms commonly used in the real estate and mortgage marketplace. A Annual Percentage Rate (APR): The cost of Appraisal: A professional analysis used a loan or other financing as an annual rate. to estimate the value of the property. This The APR includes the interest rate, points, includes examples of sales of similar prop- broker fees and certain other credit charges erties. a borrower is required to pay. Appraiser: A professional who conducts an Annuity: An amount paid yearly or at other analysis of the property, including examples regular intervals, often at a guaranteed of sales of similar properties in order to de- minimum amount. Also, a type of insurance velop an estimate of the value of the prop- policy in which the policy holder makes erty. The analysis is called an “appraisal.” payments for a fixed period or until a stated age, and then receives annuity payments Appreciation: An increase in the market from the insurance company. -

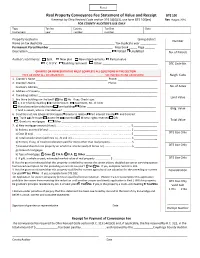

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt DTE 100 If exempt by Ohio Revised Code section 319.54(G)(3), use form DTE 100(ex) Rev 1/14 FOR COUNTY AUDITOR’S USE ONLY Type Tax list County Tax Dist Date Instrument year number number Property located in ____________________________________________________________ taxing district Number Name on tax duplicate ____________________________________________ Tax duplicate year __________ Permanent Parcel Number _______________________________________ Map book _____ Page ______ Description ___________________________________________________ Platted Unplatted No. of Parcels Auditor’s comments: Split New plat New improvements Partial value C.A.U.V. Building removed Other __________________________________ DTE Code No. GRANTEE OR REPRESENTATIVE MUST COMPLETE ALL QUESTIONS IN THIS SECTION TYPE OR PRINT ALL INFORMATION SEE INSTRUCTIONS ON REVERSE Neigh. Code 1. Grantor’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ 2. Grantee’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ Grantee’s Address__________________________________________________________________________________ No. of Acres 3. Address of Property ________________________________________________________________________________ 4. Tax billing address _________________________________________________________________________________ Land Value 5. Are there buildings on the land? Yes No If yes, Check type: 1, 2 or 3 family dwelling Condominium -

Conveyancing and the Law of Real Property

September 2014 - ISSUE 19 Conveyancing and The Law of Real Property The questions may be asked what is Conveyancing and why is Property Rules and his first act must be to undertake an inves‐ it attached to the Law of Real Property. tigation into the title of the Vendor’s property. This search which must be conducted in the Register of Deeds and should When dealing with the Law of Real Property there are two involve a period of time of thirty years or longer in the case fundamental points which must be understood‐‐‐ where the date of the Vendor’s Deed is older than thirty years. (i) You acquire knowledge of the rights and liabilities attached to the interests of the owner in the land and The Cause List search is undertaken in the Supreme Court Registry and the purpose of which is to ascertain whether (ii) The foundation of the Rules of Conveyancing. there are any liens pending against the Vendor in the Su‐ preme Court Register. If there are pending liens, they must be It is not easy to distinguish accurately between Real Property settled by the Vendor before he is able to sell the property. and Conveyancing. It is said that Real Property deals with the rights and liabilities of land owners. Conveyancing on the The original documents of title must be produced by the Ven‐ other hand is the art of creating and transferring rights in land dor and delivered to the attorney for review. I the Vendor is and thus the Rules of Conveyancing and the Law of Real Prop‐ unable to produce the same and the attorney has found the erty cannot be distinguished as separate subjects though re‐ title to be good and marketable, then the Vendor must sign lated closely but should be distinguished as two parts of one and swear an Affidavit of Loss in respect of such lost or mis‐ subject of land law. -

Real & Personal Property

CHAPTER 5 Real Property and Personal Property CHRIS MARES (Appleton, Wsconsn) hen you describe property in legal terms, there are two types of property. The two types of property Ware known as real property and personal property. Real property is generally described as land and buildings. These are things that are immovable. You are not able to just pick them up and take them with you as you travel. The definition of real property includes the land, improvements on the land, the surface, whatever is beneath the surface, and the area above the surface. Improvements are such things as buildings, houses, and structures. These are more permanent things. The surface includes landscape, shrubs, trees, and plantings. Whatever is beneath the surface includes the soil, along with any minerals, oil, gas, and gold that may be in the soil. The area above the surface is the air and sky above the land. In short, the definition of real property includes the earth, sky, and the structures upon the land. In addition, real property includes ownership or rights you may have for easements and right-of-ways. This may be for a driveway shared between you and your neighbor. It may be the right to travel over a part of another person’s land to get to your property. Another example may be where you and your neighbor share a well to provide water to each of your individual homes. Your real property has a formal title which represents and reflects your ownership of the real property. The title ownership may be in the form of a warranty deed, quit claim deed, title insurance policy, or an abstract of title. -

Real Property Conveyance Fee

Real Property Conveyance Fee tate law establishes a mandatory conveyance fee that is exempt from federal income taxation, when on the transfer of real property. The fee is calculated the transfer is without consideration and furthers the Sbased on a percentage of the property value that is agency’s charitable or public purpose. transferred. In addition to the mandatory fee, all but one • when property is sold to provide or release security county levies a permissive real property transfer fee. The for a debt, or for delinquent taxes, or pursuant to a revenue from both the mandatory fee and the permissive court order. fee is deposited in the general fund of the county in which • when a corporation transfers property to a stock the property is located - no revenue goes to the state. In holder in exchange for their shares during a corporate 2013, the latest year for which data is available, convey reorganization or dissolution. ance fees generated approximately $108.7 million in rev • when property is transferred by lease, unless the enues to counties: $34.0 million from mandatory fees and lease is for a term of years renewable forever. $74.7 million from permissive fees. • to a grantee other than a dealer, solely for the pur pose of, and as a step in, the prompt sale to others. Taxpayer • to sales or transfers to or from a person when no (Ohio Revised Code 319.202 and 322.06) money or other valuable and tangible consideration The real property conveyance fee is paid by persons readily convertible into money is paid or is to be paid who make sales of real estate or used manufactured for the realty, and the transaction is not a gift. -

Condominium Ownership of Real Property

CHAPTER 47-04.1 CONDOMINIUM OWNERSHIP OF REAL PROPERTY 47-04.1-01. Definitions. In this chapter, unless context otherwise requires: 1. "Common areas" means the entire project excepting all units therein granted or reserved. 2. "Condominium" is an estate in real property consisting of an undivided interest or interests in common in a portion of a parcel of real property together with a separate interest or interests in space in a structure, on such real property. 3. "Interest" means the fractional or percentage interest or interests ascribed to each unit by the declaration provided for in section 47-04.1-03. 4. "Limited common areas" means those elements designed for use by the owners of one or more but less than all of the units included in the project. 5. "Project" means the entire parcel of real property divided, or to be divided into condominiums, including all structures thereon. 6. "To divide" real property means to divide the ownership thereof by conveying one or more condominiums therein but less than the whole thereof. 7. "Unit" means the elements of a condominium which are not owned in common with the owners of other condominiums in the project. 47-04.1-02. Recording of declaration to submit property to a project. When the sole owner or all the owners, or the sole lessee or all of the lessees of a lease desire to submit a parcel of real property to a project established by this chapter, a declaration to that effect shall be executed and acknowledged by the sole owner or lessee or all of such owners or lessees and shall be recorded in the office of the recorder of the county in which such property lies. -

41.01.01 Real Property

41.01.01 Real Property Revised September 21, 2021 Next Scheduled Review: September 21, 2026 Click to view Revision History. Regulation Summary This regulation provides uniform guidance for the acquisition, disposition, lease and license of real property and delegates authority to the chief executive officers (CEO) or designees of The Texas A&M University System (system). Definitions Click to view Definitions. Regulation 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS 1.1 System Real Estate Office. Except as otherwise provided in this regulation, all activities involving the acquisition, disposition, lease and license of a surface estate, except those activities and operations commonly associated with easements and right-of-ways, will be consolidated in the System Real Estate Office (SREO) and coordinated with the appropriate member or members. 1.2 System Energy Resource Office. Except as otherwise provided in this regulation, all activities involving the acquisition, disposition and lease of a mineral estate, and those activities commonly associated with easements and right-of-ways of a surface estate, will be consolidated in the System Energy Resource Office (SERO) and coordinated with the appropriate member or members. 1.3 Intrasystem Assignment of Real Property. Subject to any legal requirements or donor restrictions, real property used primarily for member purposes will be assigned to the using member for maintenance, operation and management purposes. Real property may be reassigned by the chancellor based on the primary use or proposed use of the property. The reassignment will be evidenced by a form prepared by SREO, signed by the chancellor and maintained by SREO. 1.4 Maintenance of Inventory and Records. -

The Relationship Between Property Rights and Civil Rights Richard R

Hastings Law Journal Volume 15 | Issue 2 Article 3 1-1963 The Relationship between Property Rights and Civil Rights Richard R. B. Powell Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard R. B. Powell, The Relationship between Property Rights and Civil Rights, 15 Hastings L.J. 135 (1963). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol15/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. The Relationship Between Property Rights and Civil Rights By RICHARD R. B. POWELL LAW has, as a major function, the lubrication of the mechanisms of society. It is its task to afford people, in the accelerated closeness of modern living, a society in which they are able to live together harmoni- ously and with mutual advantage. On this approach it is not far-fetched to say that the most important internal problem of the United States in 1963 is the treatment of its minorities. This problem has generated more heat, more human hostility, more evidence of the need for better lubri- cation than any other single aspect of current society. Can "law" do a better job? If so, how? It is always easier to tell other people, living at a distance, how they can improve their behavior and their law. But, perhaps, it is more profitable to start with the behavior and the law in the community wherein we sleep. -

Texas Private Real Property Rights Preservation Act Guidelines

TEXAS PRIVATE REAL PROPERTY RIGHTS PRESERVATION ACT GUIDELINES TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1.1. The Private Real Property Rights Preservation Act 1.11. Purpose 1.12. Texas Attorney General Guidelines 1.13. Takings Impact Assessment Requirement (“TIA”) 1.2. Takings 1.21. What are takings? 1.22. Property Rights Act Definition of “Taking” 1.23. Incorporated Constitutional Definitions of “Taking” 1.24. “Regulatory Takings” or “Inverse Condemnation” Takings 1.3. Constitutional Regulatory Takings Analysis 1.31. Introduction 1.32. Federal Law 1.33. State Law 2. Applicability 2.1. Governmental Actions Covered and Exempted 2.11. Actions Covered 2.12. Actions Exempted 2.2. Takings Impact Assessment Procedures 3. Guide to Promulgating Takings Impact Assessments 3.1. Requirements for Promulgating Takings Impact Assessments 3.2. Guide to Evaluating Proposed Governmental Actions 3.21. Burden Analysis 3.22. Takings Impact Analysis Endnotes 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. The Private Real Property Rights Preservation Act 1.11. Purpose “The Private Real Property Rights Preservation Act,” Texas Government Code chapter 2007 (the Property Rights Act), represents a basic charter for the protection of private real property rights in Texas. 1 The Property Rights Act is the Legislature’s acknowledgment of the importance of protecting private real property interests in Texas. The purpose of the act is to ensure that certain governmental entities2 make a careful evaluation of their actions regarding private real property rights, and that those entities act according to the letter and spirit of the Property Rights Act. In short, the Property Rights Act is another instrument to ensure open and responsible government for Texans. -

Easements in Texas

Easements in Texas Judon Fambrough Senior Lecturer and Attorney at Law Technical Report 422 Easements in Texas Judon Fambrough Senior Lecturer and Attorney at Law Revised September 2013 © 2013, Real Estate Center. All rights reserved. Contents 1 Summary 1 Private Easements in Texas 2 Creation of Private Easements 5 Termination of Private Easements 6 Public Easements in Texas 6 Easements by Dedication 11 Termination of Public Easements 12 Conclusion 13 Appendix A. Synopsis of Private Easements 14 Appendix B. Synopsis of Public Easements 15 Glossary Easements in Texas Judon Fambrough Senior Lecturer and Attorney at Law Summary Easements play a vital role in everyone’s life. People daily traverse easements either granted, dedicated or condemned for public rights-of-way. Also, people constantly use energy transported along pipeline and utility easements. In rural areas, many tracts of land not served by public roadways would be rendered practically valueless if it were not for private easements crossing neighboring properties. An easement is defined as a right, privilege or advantage in real property, existing distinct from the own- ership of the land. In other words, easements consist of an interest (or estate) in real property that does not constitute full ownership. Most commonly, an easement entails the right of a person (or the public) to use the land of another in a certain manner. Easements should not be confused with licenses. A license is merely permission given to an individual to do some act or acts on the land of another. It does not give rise to an interest in land as do easements. -

Document Definitions

Document Definitions *** Disclaimer : Recorded instruments are legal documents, and it is highly advisable a licensed title company or real estate attorney be involved in the creation and execution of any document. The Recorder of Deeds is providing these basic document definitions to help consti tuents have a basic understanding of the different types of recording. There are other documents available to record but this is a basic list of the main types. Please see an attorney or title company for forms.*** ***A title search provides constructive notice of any encumbrances, easements , or restrictions on the property being conveyed, and is generally considered part of a buyer's due diligence in the process of purchasing real estate. Buyers can also purchase title insurance to protect against title defects. *** This document is not intended to nor does it purport to provide legal advice. You should consult an attorney if you have questions. Conveyances of property: Warranty deed (WD): A warranty deed is a type of deed where the grantor (seller) guarantees that he or she holds clear title to a piece of real estate and has a right to sell it to the grantee (buyer). This is in contrast to a quitclaim deed, where the seller does not guarantee that he or she holds title to a piece of real estate. Quitclaim Deed (QC): A quitclaim deed is a legal instrument which is used to transfer interest in real property, the entity transferring their interest is called the grantor , and when the quitclaim deed is properly completed and executed it transfers any interest the grantor has in the property to a recipient, called the grantee. -

Real Property ACQUISITION Handbook How the U.S

Real Property ACQUISITION Handbook How the U.S. General Services Administration Acquires Real Property for Programs and Projects GSA Public Buildings Service Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 2 CommonT erms Used in Acquiring Real Property ............................................................. 3 Property Appraisal and the Determination of Just Compensation ................................ 6 Negotiations ........................................................................................................................ 9 Settlement and Condemnation .........................................................................................12 Project Contacts ................................................................................................................13 GSA Public Buildings Service | 1 Federal programs designed to benefit the public may result in the acquisition of private property and sometimes in the displacement of people from their residences, places of business or farms. The Fifth Amendment to the United States The acquisition itself does not need to be Constitution provides that private property may Federally funded for the Uniform Act to apply. not be taken for public use without the payment If Federal funds are used in any phase of the of just compensation. To provide uniform and program or project, the rules and regulations of equitable treatment of persons whose property the Uniform