Real Property Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk

Federal Trade Commission ftc.gov The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk Buying a home can be exciting. It also can be somewhat daunting, even if you’ve done it before. You will deal with mortgage options, credit reports, loan applications, contracts, points, appraisals, change orders, inspections, warranties, walk-throughs, settlement sheets, escrow accounts, recording fees, insurance, taxes...the list goes on. No doubt you will hear and see words and terms you’ve never heard before. Just what do they all mean? The Federal Trade Commission, the agency that promotes competition and protects consumers, has prepared this glossary to help you better understand the terms commonly used in the real estate and mortgage marketplace. A Annual Percentage Rate (APR): The cost of Appraisal: A professional analysis used a loan or other financing as an annual rate. to estimate the value of the property. This The APR includes the interest rate, points, includes examples of sales of similar prop- broker fees and certain other credit charges erties. a borrower is required to pay. Appraiser: A professional who conducts an Annuity: An amount paid yearly or at other analysis of the property, including examples regular intervals, often at a guaranteed of sales of similar properties in order to de- minimum amount. Also, a type of insurance velop an estimate of the value of the prop- policy in which the policy holder makes erty. The analysis is called an “appraisal.” payments for a fixed period or until a stated age, and then receives annuity payments Appreciation: An increase in the market from the insurance company. -

Ethical Behavior in Office: Know the Law, Trust Your Conscience

Ethical Behavior in Office: Know the Law, Trust Your Conscience by John Hubbard have been a city attorney since 1972, nice enough to review these materials. It’s Not Just Statutory and I have been the Dunedin city at- Any misstatements or typographical Long before the people of Florida Itorney since 1974. During that time, errors are mine, not his. put in their constitution that we would I have had extensive experience with have an ethics law, certain principles Florida’s ethics statute and how it af- A Brief Overview of the of appropriate conduct for an elected fects the elected officials and other em- official or a public employee were ployees in the cities I have represented. Ethics Law (Chapter 112, articulated in the common law (case It seems to be the case with many Part III, Florida Statutes) law) of Florida. communities that there is a very lim- In the case of Lainhart v. Burr in ited or no discussion of the state’s The ethics law in the State of Florida 1905, the Florida Supreme Court ruled ethics statute initiated by those cities. is based primarily on three principles: that a county commissioner could Public officials who are willing to at- 1. “A public office is a public not buy supplies for the county from tend the Institute of Elected Municipal trust.” himself. At least two of the underlying Officials (IEMO) programs get a two- 2. A situation that “tempts to principles are implicated here: hour training session on the statute. dishonor.” 1. No man can serve two masters; However, even that much time is not 3. -

Homecoming 1968 Law Center Building Dedic A1tio ~

AUGU T , 1968 VOL. V, NO. 2 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA, COLLEGE OF LAW LAW CENTER BUILDING DEDIC A1TIO ~ Plan are beinu formulated for the dedication of the new Law Center Building on Febr:ary l , 1969. The dedicatory address will be delivered by Chief Justice Earl Warren on the afternoon of February 1, a aturday. This main event will be preceded by a lecture and panel discus ion on a legal subject of current interest during the morning. It is tentatively planned to hold a ocial hour and banquet on the evening of February 1 or January 31. The Dedication will also be our Law R eunion ob ervance for 1969. Please mark this date on your calendar. Gainesville motels are accepting re ervation . Water Law Center - University of Florida The College of Law has received a federal grant to support the e tab ii hment of a Center of Competence in Water Law in the Ea tern nited State . The Office of Water R esource R esearch of the United tates De partment of the Interior will provide 71,381 toward a total project cost of $75,145 for the coming year. Dean Frank E. Maloney will act as Principal Inve tigator for the project. The taff of the new Center will review major English language literature ources and locate and index all In recent state-wide competition Florida's Moot Court team took both significant articles, books and monograph pertinent to water law in the first and second place . T eam members and their team placing are: (Left geographical area east of the Mi si sippi River. -

Why We Should Abolish Florida's Elected Cabinet

Florida State University Law Review Volume 6 Issue 3 Article 5 Summer 1978 Why We Should Abolish Florida's Elected Cabinet Jon C. Moyle Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Jon C. Moyle, Why We Should Abolish Florida's Elected Cabinet, 6 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 591 (1978) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol6/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHY WE SHOULD ABOLISH FLORIDA'S ELECTED CABINET JON C. MOYLE* Over the years I have observed Florida's elected cabinet system and its role in the political process in Florida. I have been involved in several cabinet campaigns, and at one time I argued vigorously in favor of the elected cabinet system. But that was before I under- stood how that system really works. The St. PetersburgEvening Independent has described the Flor- ida cabinet system very appropriately: It's like the Abominable Snowman. It's unknown, mysterious. You hear about it in a news report or see it in a headline. Few have actually seen it, yet many believe what they are told about it. And it leaves big footprints.' I have personally observed some of these footprints. I have heard Cabinet officials defend the cabinet system on the basis of open- ness in government while obscuring the fact that the most import- ant work of the Cabinet in the executive branch is conducted be- hind closed doors. -

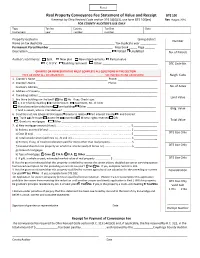

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt DTE 100 If exempt by Ohio Revised Code section 319.54(G)(3), use form DTE 100(ex) Rev 1/14 FOR COUNTY AUDITOR’S USE ONLY Type Tax list County Tax Dist Date Instrument year number number Property located in ____________________________________________________________ taxing district Number Name on tax duplicate ____________________________________________ Tax duplicate year __________ Permanent Parcel Number _______________________________________ Map book _____ Page ______ Description ___________________________________________________ Platted Unplatted No. of Parcels Auditor’s comments: Split New plat New improvements Partial value C.A.U.V. Building removed Other __________________________________ DTE Code No. GRANTEE OR REPRESENTATIVE MUST COMPLETE ALL QUESTIONS IN THIS SECTION TYPE OR PRINT ALL INFORMATION SEE INSTRUCTIONS ON REVERSE Neigh. Code 1. Grantor’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ 2. Grantee’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ Grantee’s Address__________________________________________________________________________________ No. of Acres 3. Address of Property ________________________________________________________________________________ 4. Tax billing address _________________________________________________________________________________ Land Value 5. Are there buildings on the land? Yes No If yes, Check type: 1, 2 or 3 family dwelling Condominium -

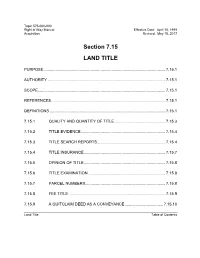

Right of Way Manual, Section 4.1, Land Title

Topic 575-000-000 Right of Way Manual Effective Date: April 15, 1999 Acquisition Revised: May 18, 2017 Section 7.15 LAND TITLE PURPOSE ............................................................................................................... 7.15.1 AUTHORITY ........................................................................................................... 7.15.1 SCOPE .................................................................................................................... 7.15.1 REFERENCES ........................................................................................................ 7.15.1 DEFINITIONS ......................................................................................................... 7.15.1 7.15.1 QUALITY AND QUANTITY OF TITLE .............................................. 7.15.3 7.15.2 TITLE EVIDENCE ............................................................................. 7.15.4 7.15.3 TITLE SEARCH REPORTS .............................................................. 7.15.4 7.15.4 TITLE INSURANCE .......................................................................... 7.15.7 7.15.5 OPINION OF TITLE .......................................................................... 7.15.8 7.15.6 TITLE EXAMINATION ...................................................................... 7.15.8 7.15.7 PARCEL NUMBERS......................................................................... 7.15.8 7.15.8 FEE TITLE ....................................................................................... -

Constitutional Prohibitions Affecting Criminal Laws

The Florida Senate Issue Brief 2011-212 October 2010 Committee on Criminal Justice CONSTITUTIONAL PROHIBITIONS AFFECTING CRIMINAL LAWS Statement of the Issue The purpose of this interim project brief is to provide legislators with information they may use to assess whether legislation is susceptible to various constitutional challenges and to craft legislation to avoid those challenges. Successful constitutional challenges can have serious consequences, such as invalidating criminal laws or provisions, vacating or reducing sentences, or releasing offenders from prison earlier than projected. Discussion Federal and State Court Jurisdiction Controlling law regarding the constitutionality of a state criminal law may or may not emanate from the highest state or federal court. Lower court decisions on constitutional questions may be controlling law and may necessitate legislation to correct a constitutional defect. Federal and state courts have concurrent jurisdiction over federal constitutional questions involving state statutes.1 The United States Supreme Court is the “final arbiter of federal constitutional law,” if it exercises its discretionary jurisdiction.2 “The court of last resort of each sovereign state is the final arbiter as to whether … [a state statute] conforms to its own constitution[.]”3 However, while the Florida Supreme Court is the highest state court and its decisions are binding on all of the Florida state courts, not every constitutional question reaches the Florida Supreme Court. “[D]ecisions of the district courts of appeal represent the law of Florida unless and until they are overruled” by the Florida Supreme Court.4 Further, absent interdistrict conflict or being overruled by the Florida Supreme Court, the decision of a single district court of appeal is controlling law on all state trial courts5 and state agencies.6 “Facial” Challenge and “As Applied” Challenge Some constitutional challenges are directed at state criminal laws as enacted. -

Conveyancing and the Law of Real Property

September 2014 - ISSUE 19 Conveyancing and The Law of Real Property The questions may be asked what is Conveyancing and why is Property Rules and his first act must be to undertake an inves‐ it attached to the Law of Real Property. tigation into the title of the Vendor’s property. This search which must be conducted in the Register of Deeds and should When dealing with the Law of Real Property there are two involve a period of time of thirty years or longer in the case fundamental points which must be understood‐‐‐ where the date of the Vendor’s Deed is older than thirty years. (i) You acquire knowledge of the rights and liabilities attached to the interests of the owner in the land and The Cause List search is undertaken in the Supreme Court Registry and the purpose of which is to ascertain whether (ii) The foundation of the Rules of Conveyancing. there are any liens pending against the Vendor in the Su‐ preme Court Register. If there are pending liens, they must be It is not easy to distinguish accurately between Real Property settled by the Vendor before he is able to sell the property. and Conveyancing. It is said that Real Property deals with the rights and liabilities of land owners. Conveyancing on the The original documents of title must be produced by the Ven‐ other hand is the art of creating and transferring rights in land dor and delivered to the attorney for review. I the Vendor is and thus the Rules of Conveyancing and the Law of Real Prop‐ unable to produce the same and the attorney has found the erty cannot be distinguished as separate subjects though re‐ title to be good and marketable, then the Vendor must sign lated closely but should be distinguished as two parts of one and swear an Affidavit of Loss in respect of such lost or mis‐ subject of land law. -

Real & Personal Property

CHAPTER 5 Real Property and Personal Property CHRIS MARES (Appleton, Wsconsn) hen you describe property in legal terms, there are two types of property. The two types of property Ware known as real property and personal property. Real property is generally described as land and buildings. These are things that are immovable. You are not able to just pick them up and take them with you as you travel. The definition of real property includes the land, improvements on the land, the surface, whatever is beneath the surface, and the area above the surface. Improvements are such things as buildings, houses, and structures. These are more permanent things. The surface includes landscape, shrubs, trees, and plantings. Whatever is beneath the surface includes the soil, along with any minerals, oil, gas, and gold that may be in the soil. The area above the surface is the air and sky above the land. In short, the definition of real property includes the earth, sky, and the structures upon the land. In addition, real property includes ownership or rights you may have for easements and right-of-ways. This may be for a driveway shared between you and your neighbor. It may be the right to travel over a part of another person’s land to get to your property. Another example may be where you and your neighbor share a well to provide water to each of your individual homes. Your real property has a formal title which represents and reflects your ownership of the real property. The title ownership may be in the form of a warranty deed, quit claim deed, title insurance policy, or an abstract of title. -

How Syrian Refugee Families Are Coping During COVID-19

Tragedy Tears Through Lebanon. Syrians Are Marginalized More Than Ever. As told by Syrian refugees whose lives remain in British Columbia, but compassion flies back home. Syrian refugee family’s youngest daughters, Nour Khalaf (nine years old) standing behind her little sister, Sarah Khalaf (three years old). PRINCE GEORGE, Canada - An eager ray of Saturday sunshine trickles in through Syrian refugee Aliyah Kora's window. The week has finally presented its gift. She instinctively goes downstairs, decamping to her living room. With her husband selling food at the local market and her five children fast asleep, this is the time she has for herself, her one respite, to help quiet the onslaught of worries that plague her thoughts. "Mama?" Her voice makes the turbulent journey to Turkey via WhatsApp, before reaching the ear of her mother. Though she dearly wishes to be in Syria with the rest of her children, Aliyah's mother seeks medical attention, a practically impossible phenomenon in her hometown, Aleppo, stemming from the sheer enormity of the cost. Aliyah's mother is in dire need of heart surgery, having been turned away from Lebanon she remains on the outskirts of Turkey. Aliyah spends the rest of the morning connecting with her brothers and sisters, who have been scattered helplessly throughout Syria, with some edging towards the borders, where food is scarce and death prevailing. The usual tranquility this morning brings her, is however, clouded. Burdened by a fresh layer of misery, afflicting displaced Syrians today, that she so narrowly escaped. This haze of sorrow came about on 4th August 2020 when an explosion fuelled by a large amount of ammonium nitrate stored at the port of Lebanon's capital city, Beirut, ripped through the city. -

The Greening of Florida's Constitution 577

THE GREENING OF FLORIDA’S CONSTITUTION Clay Henderson* I. INTRODUCTION Florida’s Constitution, like other state constitutions, is the organic law of the land. It defines the unique structure of its state and local government, establishes rights of its citizens, distributes power amongst branches of government, and places limitations on that power. Unlike the U.S. Constitution, state constitutions are more detailed, contain more issues, and are otherwise a limitation on the power of the state.1 Thus, while the U.S. Constitution makes no mention of environmental protection or natural resource conservation, many state constitutions do, as they are far more detailed, generally more modern, and much easier to amend.2 Indeed, environmental law often entails cooperative federalism, where the federal government enacts broad national environmental goals while states are left to implement programs and policies to achieve those goals.3 Florida’s Constitution provides authorization for statutory and regulatory environmental provisions, as well as proprietary functions of government. Inasmuch as any constitution is a “living document,”4 the Florida Constitution reflects the * © 2020, Clay Henderson. All rights reserved. J.D., Samford University Cumberland School of Law, 1979; B.A., Stetson University, 1977. The Author has long been associated with environmental policy in Florida. He was elected to two terms on the Volusia County Council and was appointed to various boards, including the 1997–1998 Constitution Revision Commission, Florida Greenways Coordinating Council, Administrative Procedure Act Review Commission, and Property Rights Study Commission. He sponsored or participated in drafting many of the environmental provisions of the Florida Constitution. He is retired faculty at Stetson University and adjunct professor of law at Stetson University College of Law. -

The Doctrine of After-Acquired Title

SMU Law Review Volume 11 Issue 2 Article 8 1957 The Doctrine of After-Acquired Title Charles Robert Dickenson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Charles Robert Dickenson, Comment, The Doctrine of After-Acquired Title, 11 SW L.J. 217 (1957) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol11/iss2/8 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. THE DOCTRINE OF AFTER-ACQUIRED TITLE INTRODUCTION This Comment will discuss briefly some of the problems which can arise when one person attempts by a valid instrument to convey more title than he actually has and subsequently acquires the title which he had purported to convey. Historically, in such a case the grantor is estopped to assert his after-acquired title against his grantee.' It has been said that this result is achieved through estoppel by deed rather than by estoppel in pais;' and that, therefore, there is no neces- sity for an adjudication of the rights of the parties in such a case;$ and that there is no necessity for showing a change in position of the party asserting the estoppel.4 Tiffany states that there is no necessity of regarding the after- acquired title as actually passing to the grantee.' However, there are numerous decisions and dicta in this country to the effect that the conveyance actually passes the grantor's after-acquired legal title to the grantee.! There have been,' and still are,' a number of statutory provisions to this effect in various states.