GPR101, an Orphan GPCR with Roles in Growth and Pituitary Tumorigenesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXVIII. G protein-coupled receptor list Citation for published version: Davenport, AP, Alexander, SPH, Sharman, JL, Pawson, AJ, Benson, HE, Monaghan, AE, Liew, WC, Mpamhanga, CP, Bonner, TI, Neubig, RR, Pin, JP, Spedding, M & Harmar, AJ 2013, 'International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXVIII. G protein-coupled receptor list: recommendations for new pairings with cognate ligands', Pharmacological reviews, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 967-86. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.112.007179 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1124/pr.112.007179 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Pharmacological reviews Publisher Rights Statement: U.S. Government work not protected by U.S. copyright General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 1521-0081/65/3/967–986$25.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1124/pr.112.007179 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Pharmacol Rev 65:967–986, July 2013 U.S. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Saikat Mukhopadhyay

Updated June 2021 SAIKAT MUKHOPADHYAY Assistant Professor, Cell Biology, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas. W.W. Caruth, Jr. Scholar in Biomedical Research, CPRIT Scholar in Cancer Research. UT Southwestern Medical Center, Email: [email protected] 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard Ph: 214-648-3853 Dallas, Texas, 75390. Lab url: http://www.utsouthwestern.edu/labs/mukhopadhyay/ Google Scholar url: http://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=en&user=PUKbgQ0AAAAJ EDUCATION 2008-2012 Postdoctoral Fellow, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA. 2002-2008 PhD, Biology, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA. 1999-2002 MD, Biochemistry, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. 1992-1998 MBBS, Medical College, Calcutta, India. POSITIONS AND EMPLOYMENT 2013- Assistant Professor, Department of Cell Biology, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas. 2013- Member, Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center, UT Southwestern 2013- Member, Development track, Kidney cancer program, UT Southwestern PUBLICATIONS (#corresponding or ##co-corresponding author) 1. Palicharla, V., Hwang, S., Somatilaka, B., Badgandi, H. B., Legue, E, Shimada, I, Tran, V., Woodruff, J., Liem, K, and Mukhopadhyay, S#. (2021). Interactions between TULP3 tubby domain cargo site and ARL13B amphipathic helix promote lipidated protein transport to cilia. bioRxiv. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.25.445488 2. Hwang, S., Somatilaka, B., White, K., and Mukhopadhyay, S#. (2021). Gpr161 ciliary pools prevent hedgehog pathway hyperactivation phenotypes specifically from lack of Gli transcriptional repression. bioRxiv (in revison, eLife). doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.07.425654. 1 Updated June 2021 3. Constable, S and Mukhopadhyay, S## (2020). Ubiquitin tunes hedgehog in matters of the heart. Developmental Cell, 55, 385-386. PMID. 33232673. 4. -

G Protein-Coupled Receptors

S.P.H. Alexander et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: G protein-coupled receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology (2015) 172, 5744–5869 THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: G protein-coupled receptors Stephen PH Alexander1, Anthony P Davenport2, Eamonn Kelly3, Neil Marrion3, John A Peters4, Helen E Benson5, Elena Faccenda5, Adam J Pawson5, Joanna L Sharman5, Christopher Southan5, Jamie A Davies5 and CGTP Collaborators 1School of Biomedical Sciences, University of Nottingham Medical School, Nottingham, NG7 2UH, UK, 2Clinical Pharmacology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 0QQ, UK, 3School of Physiology and Pharmacology, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TD, UK, 4Neuroscience Division, Medical Education Institute, Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, University of Dundee, Dundee, DD1 9SY, UK, 5Centre for Integrative Physiology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, EH8 9XD, UK Abstract The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 provides concise overviews of the key properties of over 1750 human drug targets with their pharmacology, plus links to an open access knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands (www.guidetopharmacology.org), which provides more detailed views of target and ligand properties. The full contents can be found at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/ 10.1111/bph.13348/full. G protein-coupled receptors are one of the eight major pharmacological targets into which the Guide is divided, with the others being: ligand-gated ion channels, voltage-gated ion channels, other ion channels, nuclear hormone receptors, catalytic receptors, enzymes and transporters. These are presented with nomenclature guidance and summary information on the best available pharmacological tools, alongside key references and suggestions for further reading. -

Multi-Functionality of Proteins Involved in GPCR and G Protein Signaling: Making Sense of Structure–Function Continuum with In

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2019) 76:4461–4492 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-019-03276-1 Cellular andMolecular Life Sciences REVIEW Multi‑functionality of proteins involved in GPCR and G protein signaling: making sense of structure–function continuum with intrinsic disorder‑based proteoforms Alexander V. Fonin1 · April L. Darling2 · Irina M. Kuznetsova1 · Konstantin K. Turoverov1,3 · Vladimir N. Uversky2,4 Received: 5 August 2019 / Revised: 5 August 2019 / Accepted: 12 August 2019 / Published online: 19 August 2019 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 Abstract GPCR–G protein signaling system recognizes a multitude of extracellular ligands and triggers a variety of intracellular signal- ing cascades in response. In humans, this system includes more than 800 various GPCRs and a large set of heterotrimeric G proteins. Complexity of this system goes far beyond a multitude of pair-wise ligand–GPCR and GPCR–G protein interactions. In fact, one GPCR can recognize more than one extracellular signal and interact with more than one G protein. Furthermore, one ligand can activate more than one GPCR, and multiple GPCRs can couple to the same G protein. This defnes an intricate multifunctionality of this important signaling system. Here, we show that the multifunctionality of GPCR–G protein system represents an illustrative example of the protein structure–function continuum, where structures of the involved proteins represent a complex mosaic of diferently folded regions (foldons, non-foldons, unfoldons, semi-foldons, and inducible foldons). The functionality of resulting highly dynamic conformational ensembles is fne-tuned by various post-translational modifcations and alternative splicing, and such ensembles can undergo dramatic changes at interaction with their specifc partners. -

1 Supplemental Material Maresin 1 Activates LGR6 Receptor

Supplemental Material Maresin 1 Activates LGR6 Receptor Promoting Phagocyte Immunoresolvent Functions Nan Chiang, Stephania Libreros, Paul C. Norris, Xavier de la Rosa, Charles N. Serhan Center for Experimental Therapeutics and Reperfusion Injury, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA. 1 Supplemental Table 1. Screening of orphan GPCRs with MaR1 Vehicle Vehicle MaR1 MaR1 mean RLU > GPCR ID SD % Activity Mean RLU Mean RLU + 2 SD Mean RLU Vehicle mean RLU+2 SD? ADMR 930920 33283 997486.5381 863760 -7% BAI1 172580 18362 209304.1828 176160 2% BAI2 26390 1354 29097.71737 26240 -1% BAI3 18040 758 19555.07976 18460 2% CCRL2 15090 402 15893.6583 13840 -8% CMKLR2 30080 1744 33568.954 28240 -6% DARC 119110 4817 128743.8016 126260 6% EBI2 101200 6004 113207.8197 105640 4% GHSR1B 3940 203 4345.298244 3700 -6% GPR101 41740 1593 44926.97349 41580 0% GPR103 21413 1484 24381.25067 23920 12% NO GPR107 366800 11007 388814.4922 360020 -2% GPR12 77980 1563 81105.4653 76260 -2% GPR123 1485190 46446 1578081.986 1342640 -10% GPR132 860940 17473 895885.901 826560 -4% GPR135 18720 1656 22032.6827 17540 -6% GPR137 40973 2285 45544.0809 39140 -4% GPR139 438280 16736 471751.0542 413120 -6% GPR141 30180 2080 34339.2307 29020 -4% GPR142 105250 12089 129427.069 101020 -4% GPR143 89390 5260 99910.40557 89380 0% GPR146 16860 551 17961.75617 16240 -4% GPR148 6160 484 7128.848113 7520 22% YES GPR149 50140 934 52008.76073 49720 -1% GPR15 10110 1086 12282.67884 -

G Protein‐Coupled Receptors

S.P.H. Alexander et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: G protein-coupled receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology (2019) 176, S21–S141 THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: G protein-coupled receptors Stephen PH Alexander1 , Arthur Christopoulos2 , Anthony P Davenport3 , Eamonn Kelly4, Alistair Mathie5 , John A Peters6 , Emma L Veale5 ,JaneFArmstrong7 , Elena Faccenda7 ,SimonDHarding7 ,AdamJPawson7 , Joanna L Sharman7 , Christopher Southan7 , Jamie A Davies7 and CGTP Collaborators 1School of Life Sciences, University of Nottingham Medical School, Nottingham, NG7 2UH, UK 2Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Department of Pharmacology, Monash University, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia 3Clinical Pharmacology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 0QQ, UK 4School of Physiology, Pharmacology and Neuroscience, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TD, UK 5Medway School of Pharmacy, The Universities of Greenwich and Kent at Medway, Anson Building, Central Avenue, Chatham Maritime, Chatham, Kent, ME4 4TB, UK 6Neuroscience Division, Medical Education Institute, Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, University of Dundee, Dundee, DD1 9SY, UK 7Centre for Discovery Brain Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, EH8 9XD, UK Abstract The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20 is the fourth in this series of biennial publications. The Concise Guide provides concise overviews of the key properties of nearly 1800 human drug targets with an emphasis on selective pharmacology (where available), plus links to the open access knowledgebase source of drug targets and their ligands (www.guidetopharmacology.org), which provides more detailed views of target and ligand properties. Although the Concise Guide represents approximately 400 pages, the material presented is substantially reduced compared to information and links presented on the website. -

Genetic and Clinical Characteristics of Japanese Patients with Sporadic Somatotropinoma

2016, 63 (11), 953-963 Original Genetic and clinical characteristics of Japanese patients with sporadic somatotropinoma Ryusaku Matsumoto1), Masako Izawa2), Hidenori Fukuoka3), Genzo Iguchi3), Yukiko Odake1), Kenichi Yoshida1), Hironori Bando1), Kentaro Suda1), Hitoshi Nishizawa1), Michiko Takahashi1), Naoko Inoshita4), Shozo Yamada5), Wataru Ogawa1) and Yutaka Takahashi1) 1) Division of Diabetes and Endocrinology, Department of Internal Medicine, Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine, Kobe, Japan 2) Department of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism, Aichi Children’s Health and Medical Center, Obu, Japan 3) Division of Diabetes and Endocrinology, Kobe University Hospital, Kobe, Japan 4) Department of Pathology, Toranomon Hospital, Tokyo, Japan 5) Department of Hypothalamic and Pituitary Surgery, Toranomon Hospital, Tokyo, Japan Abstract. Most of acromegaly is caused by a sporadic somatotropinoma and a couple of novel gene mutations responsible for somatotropinoma have recently been reported. To determine the cause of sporadic somatotropinoma in Japanese patients, we analyzed 61 consecutive Japanese patients with somatotropinoma without apparent family history. Comprehensive genetic analysis revealed that 31 patients harbored guanine nucleotide-binding protein, alpha stimulating (GNAS) mutations (50.8%) and three patients harbored aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein (AIP) mutations (4.9%). No patients had G protein-coupled receptor 101 (GPR101) mutations. The patients in this cohort study were categorized into three groups of AIP, GNAS, and others and compared the clinical characteristics. The AIP group exhibited significantly younger age at diagnosis, larger tumor, and higher nadir GH during oral glucose tolerance test. In all patients with AIP mutation, macro- and invasive tumor was detected and repetitive surgery or postoperative medical therapy was needed. One case showed a refractory response to postoperative somatostatin analogue (SSA) but after the addition of cabergoline as combined therapy, serum IGF-I levels were controlled. -

Hedgehog and Gpr161: Regulating Camp Signaling in the Primary Cilium

cells Review Hedgehog and Gpr161: Regulating cAMP Signaling in the Primary Cilium Philipp Tschaikner 1,2 , Florian Enzler 1, Omar Torres-Quesada 1 , Pia Aanstad 2 and Eduard Stefan 1,* 1 Institute of Biochemistry and Center for Molecular Biosciences, University of Innsbruck, Innrain 80/82, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected] (P.T.); fl[email protected] (F.E.); [email protected] (O.T.-Q.) 2 Institute of Molecular Biology, University of Innsbruck, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +43-512-507-57531; Fax: +43-512-507-57599 Received: 22 November 2019; Accepted: 29 December 2019; Published: 3 January 2020 Abstract: Compartmentalization of diverse types of signaling molecules contributes to the precise coordination of signal propagation. The primary cilium fulfills this function by acting as a spatiotemporally confined sensory signaling platform. For the integrity of ciliary signaling, it is mandatory that the ciliary signaling pathways are constantly attuned by alterations in both oscillating small molecules and the presence or absence of their sensor/effector proteins. In this context, ciliary G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) pathways participate in coordinating the mobilization of the diffusible second messenger molecule 30,50-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). cAMP fluxes in the cilium are primarily sensed by protein kinase A (PKA) complexes, which are essential for the basal repression of Hedgehog (Hh) signaling. Here, we describe the dynamic properties of underlying signaling circuits, as well as strategies for second messenger compartmentalization. As an example, we summarize how receptor-guided cAMP-effector pathways control the off state of Hh signaling. -

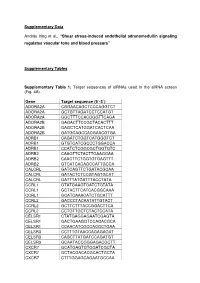

Supplementary Data, Ms Iring Et Al. Re-Revised

Supplementary Data András Iring et al., “Shear stress-induced endothelial adrenomedullin signaling regulates vascular tone and blood pressure” Supplementary Tables Supplementary Table 1. Target sequences of siRNAs used in the siRNA screen (Fig. 4A). Gene Target sequence (5´-3´) ADORA2A CGGAACAGCTCCCAGGTCT ADORA2A GCTGTTAGATCCTCCATGT ADORA2A GGCTTTCCACGGGTTCAGA ADORA2B GAGACTTCCGCTACACTTT ADORA2B GAGCTCATGGATCACTCAA ADORA2B GATGCAGCCACGAACGTGA ADRB1 CAGATCTGGTCATGGGTCT ADRB1 GTGTCATCGCCCTGGACCA ADRB1 CCATCTCGGCGCTGGTGTC ADRB2 CAAGTTCTACTTGAAGGAA ADRB2 CAACTTCTGGTGTGAGTTT ADRB2 GTCATCACAGCCATTGCCA CALCRL GATCAGTTCTGATACGCAA CALCRL GATACTCTCCGTAGTGCAT CALCRL GATTTATGATTTACCTATA CCRL1 GTATGAAGTGATCTGTATA CCRL1 GCTACTTCATCACGGCAAA CCRL1 GCATCAAACATCTGCATTT CCRL2 GACCCTACAATATTGTACT CCRL2 GCTTCTTTACCGGACTTCA CCRL2 CCTGTTGCTCTACTCCATA CELSR1 CTATGAGGAGAATCGAGTA CELSR1 GACTGAAGGTCCAGACGCA CELSR1 CCAACATCGCCACGCTGAA CELSR3 CCTTTGTAACCAGAGAGAT CELSR3 CAGCTTATGATCCAGATGT CELSR3 GCAATACCGGGAGACGCTT CXCR7 GCATGAGTGTGGATCGCTA CXCR7 GCTACGACACGCACTGCTA CXCR7 CTTTGGAGCAGAATGCCAA 2 ELTD1 CTCTTCTAATTCAACTCTT ELTD1 CAAGTTTATTACTAATGAT ELTD1 GTACCATACAGCTATAGTA FZD1 GTAACCAATGCCAAACTTT FZD1 GATTAGCCACCGAAATAAA FZD1 CAGTGTTCCGCCGAGCTCA FZD2 CGCTTTGCGCGCCTCTGGA FZD2 GACATGCAGCGCTTCCGCT FZD2 CGCACTACACGCCGCGCAT FZD4 GTATGTGCTATAATATTTA FZD4 CCATTGTCATCTTGATTAT FZD4 CCAACATGGCAGTGGAAAT FZD5 GGATTTAAGGCCCAGTTTA FZD5 GACCATAACACACTTGCTT FZD5 CAAGTGATCCTGGGAAAGA FZD6 GCATTGTATCTCTTATGTA FZD6 GTGCTTACTGAGTGTCCAA FZD6 CCAATTACTGTTCCCAGAT FZD8 CCATCTGCCTAGAGGACTA -

1 1 2 3 Cell Type-Specific Transcriptomics of Hypothalamic

1 2 3 4 Cell type-specific transcriptomics of hypothalamic energy-sensing neuron responses to 5 weight-loss 6 7 Fredrick E. Henry1,†, Ken Sugino1,†, Adam Tozer2, Tiago Branco2, Scott M. Sternson1,* 8 9 1Janelia Research Campus, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, 19700 Helix Drive, Ashburn, VA 10 20147, USA. 11 2Division of Neurobiology, Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, 12 Cambridge CB2 0QH, UK 13 14 †Co-first author 15 *Correspondence to: [email protected] 16 Phone: 571-209-4103 17 18 Authors have no competing interests 19 1 20 Abstract 21 Molecular and cellular processes in neurons are critical for sensing and responding to energy 22 deficit states, such as during weight-loss. AGRP neurons are a key hypothalamic population 23 that is activated during energy deficit and increases appetite and weight-gain. Cell type-specific 24 transcriptomics can be used to identify pathways that counteract weight-loss, and here we 25 report high-quality gene expression profiles of AGRP neurons from well-fed and food-deprived 26 young adult mice. For comparison, we also analyzed POMC neurons, an intermingled 27 population that suppresses appetite and body weight. We find that AGRP neurons are 28 considerably more sensitive to energy deficit than POMC neurons. Furthermore, we identify cell 29 type-specific pathways involving endoplasmic reticulum-stress, circadian signaling, ion 30 channels, neuropeptides, and receptors. Combined with methods to validate and manipulate 31 these pathways, this resource greatly expands molecular insight into neuronal regulation of 32 body weight, and may be useful for devising therapeutic strategies for obesity and eating 33 disorders. -

Zebrafish GPR161 Contributes to Basal Hedgehog Repression in A

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/616482; this version posted April 23, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 ZEBRAFISH GPR161 CONTRIBUTES TO BASAL HEDGEHOG 2 REPRESSION IN A TISSUE-SPECIFIC MANNER 3 4 Philipp Tschaikner1, 2, Dominik Regele1, Willi Salvenmoser3, Stephan Geley4, Eduard Stefan2, Pia 5 Aanstad1 6 1Institute of Molecular Biology and Center for Molecular Biosciences, University of Innsbruck, 7 Innsbruck, Austria 8 2Institute of Biochemistry and Center for Molecular Biosciences, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, 9 Austria 10 3Institute of Zoology and Center of Molecular Bioscience Innsbruck, University of Innsbruck, 11 Innsbruck, Austria 12 4Division of Molecular Pathophysiology, Medical University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria 13 *Corresponding author: [email protected] 14 Abstract 15 Hedgehog (Hh) ligands act as morphogens to direct patterning and proliferation during embryonic 16 development. Protein kinase A (PKA) is a central negative regulator of Hh signalling, and in the 17 absence of Hh ligands, PKA activity prevents inappropriate expression of Hh target genes. The Gs- 18 coupled receptor Gpr161 contributes to the basal Hh repression machinery by activating PKA, 19 although the extent of this contribution is unclear. Here we show that loss of Gpr161 in zebrafish 20 leads to constitutive activation of low-, but not high-level Hh target gene expression in the neural 21 tube. In contrast, in the myotome, both high- and low-level Hh signalling is constitutively activated in 22 the absence of Gpr161 function.